7.5 Interprofessional Communication

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

The third IPEC competency focuses on interprofessional communication and states, “Communicate with patients, families, communities, and professionals in health and other fields in a responsive and responsible manner that supports a team approach to the promotion and maintenance of health and the prevention and treatment of disease.”[1] See Figure 7.1[2] for an image of interprofessional communication supporting a team approach. This competency also aligns with The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goal for improving staff communication.[3] See the following box for the components associated with the Interprofessional Communication competency.

Components of IPEC’s Interprofessional Communication Competency[4]

- Choose effective communication tools and techniques, including information systems and communication technologies, to facilitate discussions and interactions that enhance team function.

- Communicate information with patients, families, community members, and health team members in a form that is understandable, avoiding discipline-specific terminology when possible.

- Express one’s knowledge and opinions to team members involved in patient care and population health improvement with confidence, clarity, and respect, working to ensure common understanding of information, treatment, care decisions, and population health programs and policies.

- Listen actively and encourage ideas and opinions of other team members.

- Give timely, sensitive, constructive feedback to others about their performance on the team, responding respectfully as a team member to feedback from others.

- Use respectful language appropriate for a given difficult situation, crucial conversation, or conflict.

- Recognize how one’s uniqueness (experience level, expertise, culture, power, and hierarchy within the health care team) contributes to effective communication, conflict resolution, and positive interprofessional working relationships.

- Communicate the importance of teamwork in patient-centered care and population health programs and policies.

Transmission of information among members of the health care team and facilities is ongoing and critical to quality care. However, information that is delayed, inefficient, or inadequate creates barriers for providing quality of care. Communication barriers continue to exist in health care environments due to interprofessional team members’ lack of experience when interacting with other disciplines. For instance, many novice nurses enter the workforce without experiencing communication with other members of the health care team (e.g., providers, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, social workers, surgical staff, dieticians, physical therapists, etc.). Additionally, health care professionals tend to develop a professional identity based on their educational program with a distinction made between groups. This distinction can cause tension between professional groups due to diverse training and perspectives on providing quality patient care. In addition, a health care organization’s environment may not be conducive to effectively sharing information with multiple staff members across multiple units.

In addition to potential educational, psychological, and organizational barriers to sharing information, there can also be general barriers that impact interprofessional communication and collaboration. See the following box for a list of these general barriers.[5]

General Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration[6]

- Personal values and expectations

- Personality differences

- Organizational hierarchy

- Lack of cultural humility

- Generational differences

- Historical interprofessional and intraprofessional rivalries

- Differences in language and medical jargon

- Differences in schedules and professional routines

- Varying levels of preparation, qualifications, and status

- Differences in requirements, regulations, and norms of professional education

- Fears of diluted professional identity

- Differences in accountability and reimbursement models

- Diverse clinical responsibilities

- Increased complexity of patient care

- Emphasis on rapid decision-making

There are several national initiatives that have been developed to overcome barriers to communication among interprofessional team members. These initiatives are summarized in Table 7.5a.[7]

Table 7.5a. Initiatives to Overcome Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration[8]

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

| Teach structured interprofessional communication strategies | Structured communication strategies, such as ISBARR, handoff reports, I-PASS reports, and closed-loop communication should be taught to all health professionals. |

| Train interprofessional teams together | Teams that work together should train together. |

| Train teams using simulation | Simulation creates a safe environment to practice communication strategies and increase interdisciplinary understanding. |

| Define cohesive interprofessional teams | Interprofessional health care teams should be defined within organizations as a cohesive whole with common goals and not just a collection of disciplines. |

| Create democratic teams | All members of the health care team should feel valued. Creating democratic teams (instead of establishing hierarchies) encourages open team communication. |

| Support teamwork with protocols and procedures | Protocols and procedures encouraging information sharing across the whole team include checklists, briefings, huddles, and debriefing. Technology and informatics should also be used to promote information sharing among team members. |

| Develop an organizational culture supporting health care teams | Agency leaders must establish a safety culture and emphasize the importance of effective interprofessional collaboration for achieving good patient outcomes. |

Communication Strategies

Several communication strategies have been implemented nationally to ensure information is exchanged among health care team members in a structured, concise, and accurate manner to promote safe patient care. Examples of these initiatives are ISBARR, handoff reports, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS. Documentation that promotes sharing information interprofessionally to promote continuity of care is also essential. These strategies are discussed in the following subsections.

ISBARR

A common format used by health care team members to exchange client information is ISBARR, a mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back.[9],[10]

- Introduction: Introduce your name, role, and the agency from which you are calling.

- Situation: Provide the client’s name and location, the reason you are calling, recent vital signs, and the status of the client.

- Background: Provide pertinent background information about the client such as admitting medical diagnoses, code status, recent relevant lab or diagnostic results, and allergies.

- Assessment: Share abnormal assessment findings and your evaluation of the current client situation.

- Request/Recommendations: State what you would like the provider to do, such as reassess the client, order a lab/diagnostic test, prescribe/change medication, etc.

- Repeat back: If you are receiving new orders from a provider, repeat them to confirm accuracy. Be sure to document communication with the provider in the client’s chart.

Nursing Considerations

Before using ISBARR to call a provider regarding a changing client condition or concern, it is important for nurses to prepare and gather appropriate information. See the following box for considerations when calling the provider.

Communication Guidelines for Nurses[11]

- Have I assessed this client before I call?

- Have I reviewed the current orders?

- Are there related standing orders or protocols?

- Have I read the most recent provider and nursing progress notes?

- Have I discussed concerns with my charge nurse, if necessary?

- When ready to call, have the following information on hand:

- Admitting diagnosis and date of admission

- Code status

- Allergies

- Most recent vital signs

- Most recent lab results

- Current meds and IV fluids

- If receiving oxygen therapy, current device and L/min

- Before calling, reflect on what you expect to happen as a result of this call and if you have any recommendations or specific requests.

- Repeat back any new orders to confirm them.

- Immediately after the call, document with whom you spoke, the exact time of the call, and a summary of the information shared and received.

Read an example of an ISBARR report in the following box.

Sample ISBARR Report From a Nurse to a Health Care Provider

I: “Hello Dr. Smith, this is Jane Smith, RN from the Med-Surg unit.”

S: “I am calling to tell you about Ms. White in Room 210, who is experiencing an increase in pain, as well as redness at her incision site. Her recent vital signs were BP 160/95, heart rate 90, respiratory rate 22, O2 sat 96% on room air, and temperature 38 degrees Celsius. She is stable but her pain is worsening.”

B: “Ms. White is a 65-year-old female, admitted yesterday post hip surgical replacement. She has been rating her pain at 3 or 4 out of 10 since surgery with her scheduled medication, but now she is rating the pain as a 7, with no relief from her scheduled medication of Vicodin 5/325 mg administered an hour ago. She is scheduled for physical therapy later this morning and is stating she won’t be able to participate because of the pain this morning.”

A: “I just assessed the surgical site, and her dressing was clean, dry, and intact, but there is 4 cm redness surrounding the incision, and it is warm and tender to the touch. There is moderate serosanguinous drainage. Her lungs are clear, and her heart rate is regular. She has no allergies. I think she has developed a wound infection.”

R: “I am calling to request an order for a CBC and increased dose of pain medication.”

R: “I am repeating back the order to confirm that you are ordering a STAT CBC and an increase of her Vicodin to 10/325 mg.”

View or print an ISBARR reference card.

Handoff Reports

Handoff reports are defined by The Joint Commission as “a transfer and acceptance of patient care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing patient specific information from one caregiver to another, or from one team of caregivers to another, for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the patient’s care.”[12] In 2017 The Joint Commission issued a sentinel alert about inadequate handoff communication that has resulted in patient harm such as wrong-site surgeries, delays in treatment, falls, and medication errors.[13]

The Joint Commission encourages the standardization of critical content to be communicated by interprofessional team members during a handoff report both verbally (preferably face to face) and in written form. Critical content to communicate to the receiver in a handoff report includes the following components[14]:

- Sender contact information

- Illness assessment, including severity

- Patient summary, including events leading up to illness or admission, hospital course, ongoing assessment, and plan of care

- To-do action list

- Contingency plans

- Allergy list

- Code status

- Medication list

- Recent laboratory tests

- Recent vital signs

Several strategies for improving handoff communication have been implemented nationally, such as the Bedside Handoff Report Checklist, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS.

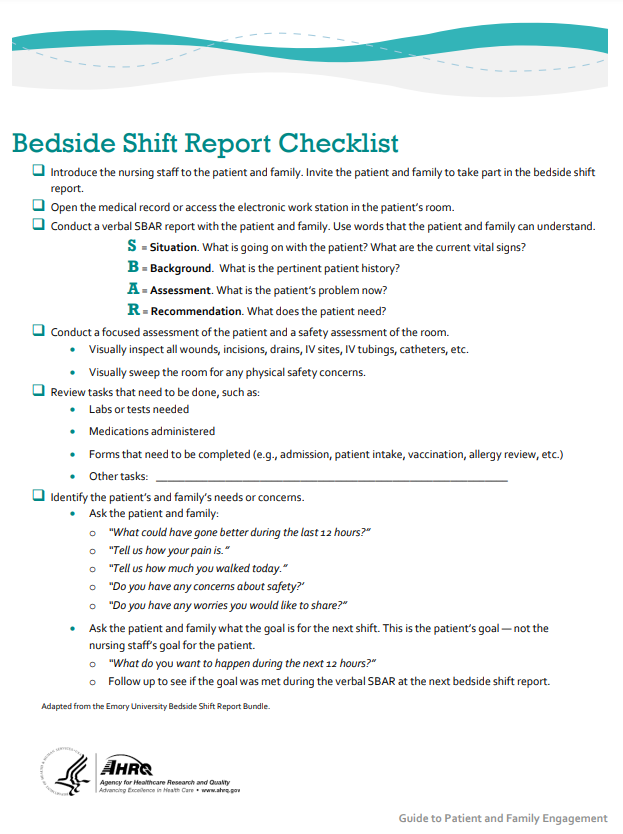

Bedside Handoff Report Checklist

See Figure 7.2[15] for an example of a Bedside Handoff Report Checklist to improve nursing handoff reports by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).[16] Although a bedside handoff report is similar to an ISBARR report, it contains additional information to ensure continuity of care across nursing shifts.

Print a copy of the AHRQ Bedside Shift Report Checklist.[17]

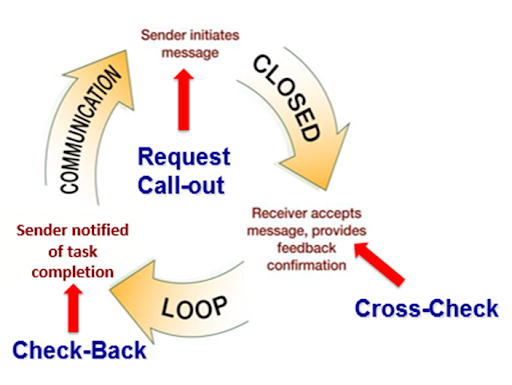

Closed-Loop Communication

The closed-loop communication strategy is used to ensure that information conveyed by the sender is heard by the receiver and completed. Closed-loop communication is especially important during emergency situations when verbal orders are being provided as treatments are immediately implemented. See Figure 7.3[18] for an illustration of closed-loop communication.

- The sender initiates the message.

- The receiver accepts the message and repeats back the message to confirm it (i.e., “Cross-Check”).

- The sender confirms the message.

- The receiver notified the sender the task was completed (i.e., “Check-Back”).

See an example of closed-loop communication during an emergent situation in the following box.

Closed-Loop Communication Example

Doctor: “Administer 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT.”

Nurse: “Give 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT?”

Doctor: “That’s correct.”

Nurse: “Benadryl 25 mg IV push given at 1125.”

I-PASS

I-PASS is a mnemonic used to provide structured communication among interprofessional team members. I-PASS stands for the following components[19]:

I: Illness severity

P: Patient summary

A: Action list

S: Situation awareness and contingency plans

S: Synthesis by receiver (i.e., closed-loop communication)

See a sample I-PASS Handoff in Table 7.5b.[20]

Table 7.5b. Sample I-PASS Verbal Handoff[21]

| I | Illness Severity | This is our sickest patient on the unit, and he’s a full code. |

|---|---|---|

| P | Patient Summary | AJ is a 4-year-old boy admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to left lower lobe pneumonia. He presented with cough and high fevers for two days before admission, and on the day of admission to the emergency department, he had worsening respiratory distress. In the emergency department, he was found to have a sodium level of 130 mg/dL likely due to volume depletion. He received a fluid bolus, and oxygen administration was started at 2.5 L/min per nasal cannula. He is on ceftriaxone. |

| A | Action List | Assess him at midnight to ensure his vital signs are stable. Check to determine if his blood culture is positive tonight. |

| S | Situations Awareness & Contingency Planning | If his respiratory distress worsens, get another chest radiograph to determine if he is developing an effusion. |

| S | Synthesis by Receiver | Ok, so AJ is a 4-year-old admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to a left lower lobe pneumonia receiving ceftriaxone, oxygen, and fluids. I will assess him at midnight to ensure he is stable and check on his blood culture. If his respiratory status worsens, I will repeat a radiograph to look for an effusion. |

Listening Skills

Effective team communication includes both the delivery and receipt of the message. Listening skills are a fundamental element of the communication loop. For nursing staff, this involves listening to clients, families, and coworkers. Active listening involves not just hearing the individual words that someone states, but also understanding the emotions and concerns behind the words. Employing active listening reflects an empathetic approach and can improve client outcomes and foster teamwork.

Nurses often serve as the communication bridge between clients, families, and other health care team members. By listening attentively to colleagues, nurses can ensure that important information is accurately conveyed, reducing the risk of misunderstandings and enhancing the overall efficiency of care delivery. This collaborative environment fosters a culture of mutual respect and support, ultimately leading to better health care outcomes.

In order to develop active listening skills, individuals should practice mindfulness and practice their communication techniques. Listening skills can be cultivated with eye contact, actions such as nodding, and demonstration of other nonverbal strategies to demonstrate engagement. Maintaining an open posture, smiling, and attentiveness are all nonverbal strategies that can facilitate communication. It is important to take measures to avoid distractions, offer a summation of the communication, and ask clarifying questions to further develop the communication.

Documentation

Accurate, timely, concise, and thorough documentation by interprofessional team members ensures continuity of care for their clients. It is well-known by health care team members that in a court of law the rule of thumb is, “If it wasn’t documented, it wasn’t done.” Any type of documentation in the electronic health record (EHR) is considered a legal document. Abbreviations should be avoided in legal documentation and some abbreviations are prohibited. Please see a list of error prone abbreviations in the box below.

Read the current list of error-prone abbreviations by the Institute of Safe Medication Practices. These abbreviations should never be used when communicating medical information verbally, electronically, and/or in handwritten applications. Abbreviations included on The Joint Commission’s “Do Not Use” list are identified with a double asterisk (**) and must be included on an organization’s “Do Not Use” list.

Nursing staff access the electronic health record (EHR) to help ensure accuracy in medication administration and document the medication administration to help ensure patient safety. Please see Figure 7.4[22] for an image of a nurse accessing a client’s EHR.

Electronic Health Record

The electronic health record (EHR) contains the following important information:

- History and Physical (H&P): A history and physical (H&P) is a specific type of documentation created by the health care provider when the client is admitted to the facility. An H&P includes important information about the client’s current status, medical history, and the treatment plan in a concise format that is helpful for the nurse to review. Information typically includes the reason for admission, health history, surgical history, allergies, current medications, physical examination findings, medical diagnoses, and the treatment plan.

- Provider orders: This section includes the prescriptions, or medical orders, that the nurse must legally implement or appropriately communicate according to agency policy if not implemented.

- Medication Administration Records (MARs): Medications are charted through electronic medication administration records (MARs). These records interface the medication orders from providers with pharmacists and are also the location where nurses document medications administered.

- Treatment Administration Records (TARs): In many facilities, treatments are documented on a treatment administration record.

- Laboratory results: This section includes results from blood work and other tests performed in the lab.

- Diagnostic test results: This section includes results from diagnostic tests ordered by the provider such as X-rays, ultrasounds, etc.

- Progress notes: This section contains notes created by nurses, providers, and other interprofessional team members regarding client care. It is helpful for the nurse to review daily progress notes by all team members to ensure continuity of care.

- Nursing care plans: Nursing care plans are created by registered nurses (RNs). Documentation of individualized nursing care plans is legally required in long-term care facilities by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and in hospitals by The Joint Commission. Nursing care plans are individualized to meet the specific and unique needs of each client. They contain expected outcomes and planned interventions to be completed by nurses and other members of the interprofessional team. As part of the nursing process, nurses routinely evaluate the client’s progress toward meeting the expected outcomes and modify the nursing care plan as needed. Read more about nursing care plans in the “Planning” section of the “Nursing Process” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Read the American Nurses Association’s Principles for Nursing Documentation.

Media Attributions

- strat3

- unnamed (3)

- Earwax

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. IPEC core competencies. https://www.ipecollaborative.org/ipec-core-competencies ↵

- “1322557028-huge.jpg” by LightField Studios is used under license from Shutterstock.com ↵

- The Joint Commission. 2021 Hospital national patient safety goals. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/national-patient-safety-goals/2021/simplified-2021-hap-npsg-goals-final-11420.pdf ↵

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. IPEC core competencies. https://www.ipecollaborative.org/ipec-core-competencies ↵

- O’Daniel, M., & Rosenstein, A. H. (2011). Professional communication and team collaboration. In: Hughes R.G. (Ed.). Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Chapter 33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2637 ↵

- O’Daniel, M., & Rosenstein, A. H. (2011). Professional communication and team collaboration. In: Hughes R.G. (Ed.). Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Chapter 33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2637 ↵

- Weller, J., Boyd, M., & Cumin, D. (2014). Teams, tribes and patient safety: Overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 90(1061), 149-154. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168 ↵

- Weller, J., Boyd, M., & Cumin, D. (2014). Teams, tribes and patient safety: Overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 90(1061), 149-154. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168 ↵

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement (n.d.). ISBAR trip tick. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/ISBARTripTick.aspx ↵

- Grbach, W., Vincent, L., & Struth, D. (2008). Curriculum developer for simulation education. QSEN Institute. https://qsen.org/reformulating-sbar-to-i-sbar-r/ ↵

- Studer Group. (2007). Patient safety toolkit – Practical tactics that improve both patient safety and patient perceptions of care. Studer Group. ↵

- Starmer, A. J., Spector, N. D., Srivastava, R., Allen, A. D., Landrigan, C. P., Sectish, T. C., & I-Pass Study Group. (2012). Transforming pediatric GME. Pediatrics, 129(2), 201-204. https://www.ipassinstitute.com/hubfs/I-PASS-mnemonic.pdf ↵

- The Joint Commission. (n.d.). Sentinel event alert 58: Inadequate hand-off reports. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sentinel-event-alert-newsletters/sentinel-event-alert-58-inadequate-hand-off-communication/ ↵

- The Joint Commission. (n.d.). Sentinel event alert 58: Inadequate hand-off reports. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sentinel-event-alert-newsletters/sentinel-event-alert-58-inadequate-hand-off-communication/ ↵

- “Strat3_Tool_2_Nurse_Chklst_508.pdf” by AHRQ is licensed under CC0 ↵

- AHRQ. (n.d.). Bedside shift report checklist. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/systems/hospital/engagingfamilies/strategy3/Strat3_Tool_2_Nurse_Chklst_508.pdf ↵

- AHRQ. (n.d.). Bedside shift report checklist. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/systems/hospital/engagingfamilies/strategy3/Strat3_Tool_2_Nurse_Chklst_508.pdf ↵

- Image is derivative of "close-loop.png" by unknown and is licensed under CC0. Access for free at https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/essentials/pocketguide.html ↵

- The Joint Commission. (n.d.). Sentinel event alert 58: Inadequate hand-off reports. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sentinel-event-alert-newsletters/sentinel-event-alert-58-inadequate-hand-off-communication/ ↵

- Starmer, A. J., Spector, N. D., Srivastava, R., Allen, A. D., Landrigan, C. P., Sectish, T. C., & I-Pass Study Group. (2012). Transforming pediatric GME. Pediatrics, 129(2), 201-204. https://www.ipassinstitute.com/hubfs/I-PASS-mnemonic.pdf ↵

- Starmer, A. J., Spector, N. D., Srivastava, R., Allen, A. D., Landrigan, C. P., Sectish, T. C., & I-Pass Study Group. (2012). Transforming pediatric GME. Pediatrics, 129(2), 201-204. https://www.ipassinstitute.com/hubfs/I-PASS-mnemonic.pdf ↵

- "Winn_Army_Community_Hospital_Pharmacy_Stays_Online_During_Power_Outage.jpg" by Flickr user MC4 Army is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

There are a variety of drugs and substances that clients may utilize for symptom management or to enhance their wellness. Nurses document clients' use of prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, herbal substances, and other supplements in the medical record. Some substances have a long half-life and have the potential to interact with new medications, so accuracy is vital. Ensuring an accurate medical record and knowledge of the different types of substances a client is taking is important for an effective nursing plan of care.

Prescription Medications

Drugs are prescribed by a licensed prescriber for a specific person's use and regulated through the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). More information about FDA approval of medications is described in the “Legal/Ethical” chapter. Prescription medications include brand-name medications and generic medications.[1]

Common Prefixes, Suffixes, And Roots For Classes Of Medication

Table 1.8 provides prefixes, suffixes, and roots associated with common prescription medications. As a nurse, familiarizing yourself with the content in the table can help you to quickly organize medications based on their name and recall their mechanism of action and identify potential interactions or side effects. This knowledge can improve your ability to safely administer medications and provide health teaching. Ultimately, this knowledge can lead to improved client outcomes, increased satisfaction, and a reduced risk of adverse events and medication errors.

Table 1.8 Common Classes of Medications, Examples, Suffixes, and Roots

| Class of Medication | Example | Common Suffixes | Common Roots |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesics | lidocaine | -caine | -morph, -morphe, -morphic |

| Antacids | omeprazole | -azole | -tidine |

| Antibiotics | levofloxacin | -mycin, -floxacin | bacter-, vir-, -cidal |

| Anticoagulants | warfarin | -arin | coagul- |

| Antidepressants | fluoxetine | -oxetine, -ipramine | serotonin, norepinephrine |

| Antihistamines | diphenhydramine | -dine, -mine | hist- |

| Anti-inflammatory | cortisone | -one | -corti-, -flam-, -prost- |

| Antipsychotics | olanzapine | -azine, -apine | dopa-, sero-, -plegia |

| Beta-blockers | metoprolol | -olol | adrenergic, beta- |

| Bronchodilators | albuterol | -terol | bronch-, -pnea |

| Corticosteroids | prednisone | -sone or -solone | |

| Diuretics | furosemide | -semide, -thiazide | -uret-, -osm- |

| Hypoglycemics | glipizide | -ide | gluc-, insulin- |

| Statins | atorvastatin | -statin | cholesterol, lipid- |

Generic Medications

Generic medications can be safe and effective alternatives to their brand-name counterparts at a significantly reduced cost. By law, generic medications must have the same chemically active ingredient in the same dose as the brand name (i.e., they must be "bio-equivalent"). However, the excipients (the base substance that holds the active chemical ingredient into a pill form (such as talc) or the flavoring can be different. Some clients do not tolerate these differences in excipients very well. When prescribing a medication, the provider must indicate that a generic substitution is acceptable. Nurses are often pivotal in completing insurance paperwork on the client's behalf if the brand-name medication is more effective or better tolerated by that particular client.[2]

When studying medications in nursing school and preparing for the NCLEX, it is important to know medications by their generic name because the NCLEX does not include brand names in their questions.

Over-the-Counter Medications

Over-the-counter (OTC) medications do not require a prescription. They can be bought at a store and may be used by multiple individuals. OTC medications are also regulated through the FDA. Some prescription medications are available for purchase as OTC in smaller doses. For example, diphenhydramine (Benadryl) is commonly prescribed as 50 mg every 6 hours, and the prescription strength is 50 mg. However, it can also be purchased OTC in 25 mg doses (or less for children.)[3]

Herbals and Supplements

Herbs and supplements may include a wide variety of substances including vitamins, minerals, enzymes, and botanicals. Supplements such as “protein powders” are marketed to build muscle mass and can contain a variety of substances that may not be appropriate for all individuals. Herbals and supplements are often considered complementary and alternative medications (CAM). Complementary and alternative medications (CAM) are types of therapies that are commonly used in conjunction with or as an alternate to traditional medical therapies. These herbal and supplement substances are not regulated by the FDA, and most have not undergone rigorous scientific testing for safety for the public. While clients may be tempted to try these herbals and supplements, there is no guarantee that they contain the ingredients listed on the label. It is also important to remember that there is a potential for adverse effects or even overdose if the herbal or supplement contains some of the same drug that was also prescribed to a client.[4] By understanding the use of CAM therapies, nurses can help their clients make informed decisions and take a holistic approach to their care. Additionally, being knowledgeable about CAM therapies can help nurses to better educate their clients on the potential benefits and risks associated with these therapies, which can help improve client outcomes and satisfaction.

Read additional information on complementary and alternative medicine at the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) Database.

As discussed previously, the American Nurses Association (ANA) defines advocacy at the individual level as educating health care consumers so they can consider actions, interventions, or choices related to their own personal beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge to achieve the desired outcome. In this way, the health care consumer learns self-management and decision-making.[5] Advocacy at the interpersonal level is defined as empowering health care consumers by providing emotional support, assistance in obtaining resources, and necessary help through interactions with families and significant others in their social support network.[6]

What does advocacy look like in a nurse’s daily practice? The following are some examples provided by an oncology nurse[7]:

- Ensure Safety. Ensure the client is safe when being treated in a health care facility and when they are discharged by communicating with case managers or social workers about the client’s need for home health or assistance after discharge so it is arranged before they go home.

- Give Clients a Voice. Give clients a voice when they are vulnerable by staying in the room with them while the doctor explains their diagnosis and treatment options to help them ask questions, get answers, and translate information from medical jargon.

- Educate. Educate clients on how to manage their current or chronic conditions to improve the quality of their everyday life. For example, clients undergoing chemotherapy can benefit from the nurse teaching them how to take their anti-nausea medication in a way that will be most effective for them and will allow them to feel better between treatments.

- Protect Patient Rights. Know clients’ wishes for their care. Advocacy may include therapeutically communicating a client’s wishes to an upset family member who disagrees with their choices. In this manner, the client’s rights are protected and a healing environment is established.

- Double-Check for Errors. Know that everyone makes mistakes. Nurses often identify, stop, and fix errors made by interprofessional team members. They flag conflicting orders from multiple providers and notice oversights. Nurses should read provider orders and carefully compare new orders to previous documentation. If an order is unclear or raises concerns, a nurse should discuss their concerns with another nurse, a charge nurse, a pharmacist, or the provider before implementing it to ensure patient safety.

- Connect Clients to Resources. Help clients find resources inside and outside the hospital to support their well-being. Know resources in your agency, such as case managers or social workers who can assist with financial concerns, advance directives, health insurance, or transportation concerns. Request assistance from agency chaplains to support spiritual concerns. Promote community resources, such as patient or caregiver support networks, Meals on Wheels, or other resources to meet their needs.

Nurses must recognize their unique position in client advocacy to empower individuals to provide them with the support and resources to make their best judgment. The intimate and continuous nature of the nurse-patient relationship places nurses in a prime position to identify and address the needs and concerns of their patients. This relationship is built on trust, empathy, and consistent interaction, which allows nurses to gain a deep understanding of their patients' values, preferences, and personal circumstances. By leveraging this close proximity and strong rapport, nurses can effectively advocate for their patients, ensuring that their voices are heard, and their wishes are respected in all aspects of care.[8]

The power of the nurse-patient relationship extends beyond the immediate clinical environment. Nurses often act as liaisons between patients and the broader health care team, facilitating communication and ensuring that patient preferences are integrated into care plans. This advocacy role is crucial in navigating complex health care systems where patients may feel overwhelmed or marginalized. Nurses can help demystify medical jargon, explain treatment options, and support patients in making informed decisions that align with their values and goals. Through education and emotional support, nurses empower patients to take an active role in their own care, enhancing patient autonomy and satisfaction.[9]

In addition to direct patient care, nurses play a pivotal role in identifying systemic issues that affect patient outcomes. Their frontline perspective provides valuable insights into the barriers patients face in accessing quality care, such as socioeconomic challenges, cultural barriers, and institutional policies. By advocating for policy changes and improvements in health care delivery, nurses contribute to creating a more equitable and patient-centered health care system. Their advocacy efforts can lead to the implementation of practices and policies that better address the needs of diverse patient populations, ultimately improving health outcomes on a broader scale.[10]

Nurses' advocacy is also essential in situations where patients are unable to speak for themselves, such as in cases of severe illness, disability, or end-of-life care. In these instances, nurses must be vigilant in recognizing and addressing the needs of vulnerable patients, ensuring that their rights and dignity are upheld. This may involve working closely with families and caregivers, coordinating with interdisciplinary teams, and navigating ethical dilemmas to provide the best possible care for the patient.