6.3 Ethical Dilemmas

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Nurses frequently find themselves involved in conflicts during patient care related to opposing values and ethical principles. These conflicts are referred to as ethical dilemmas. An ethical dilemma results from conflict of competing values and requires a decision to be made from equally desirable or undesirable options.

An ethical dilemma can involve conflicting patient’s values, nurse values, health care provider’s values, organizational values, and societal values associated with unique facts of a specific situation. For this reason, it can be challenging to arrive at a clearly superior solution for all stakeholders involved in an ethical dilemma. Nurses may also encounter moral dilemmas where the right course of action is known but the nurse is limited by forces outside their control. See Table 6.3a for an example of ethical dilemmas a nurse may experience in their nursing practice.

Table 6.3a. Examples of Ethical Issues Involving Nurses

| Workplace | Organizational Processes | Client Care |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Read more about Ethics Topics and Articles on the ANA website.

According to the American Nurses Association (ANA), a nurse’s ethical competence depends on several factors[1]:

- Continuous appraisal of personal and professional values and how they may impact interpretation of an issue and decision-making

- An awareness of ethical obligations as mandated in the Code of Ethics for Nurses With Interpretive Statements[2]

- Knowledge of ethical principles and their application to ethical decision-making

- Motivation and skills to implement an ethical decision

Nurses and nursing students must have moral courage to address the conflicts involved in ethical dilemmas with “the willingness to speak out and do what is right in the face of forces that would lead us to act in some other way.”[3] See Figure 6.7[4] for an illustration of nurses’ moral courage.

Nurse leaders and organizations can support moral courage by creating environments where nurses feel safe and supported to speak up.[5] Nurses may experience moral conflict when they are uncertain about what values or principles should be applied to an ethical issue that arises during patient care. Moral conflict can progress to moral distress when the nurse identifies the correct ethical action but feels constrained by competing values of an organization or other individuals. Nurses may also feel moral outrage when witnessing immoral acts or practices they feel powerless to change. For this reason, it is essential for nurses and nursing students to be aware of frameworks for solving ethical dilemmas that consider ethical theories, ethical principles, personal values, societal values, and professionally sanctioned guidelines such as the ANA Nursing Code of Ethics.

Moral injury felt by nurses and other health care workers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has gained recent public attention. Moral injury refers to the distressing psychological, behavioral, social, and sometimes spiritual aftermath of exposure to events that contradict deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.[6] Health care workers may not have the time or resources to process their feelings of moral injury caused by the pandemic, which can result in burnout. Organizations can assist employees in processing these feelings of moral injury with expanded employee assistance programs or other structured support programs.[7] Read more about self-care strategies to address feelings of burnout in the “Burnout and Self-Care” chapter.

Frameworks for Solving Ethical Dilemmas

Systematically working through an ethical dilemma is key to identifying a solution. Many frameworks exist for solving an ethical dilemma, including the nursing process, four-quadrant approach, the MORAL model, and the organization-focused PLUS Ethical Decision-Making model.[8] When nurses use a structured, systematic approach to resolving ethical dilemmas with appropriate data collection, identification and analysis of options, and inclusion of stakeholders, they have met their legal, ethical, and moral responsibilities, even if the outcome is less than ideal.

Nursing Process Model

The nursing process is a structured problem-solving approach that nurses may apply in ethical decision-making to guide data collection and analysis. See Table 6.3b for suggestions on how to use the nursing process model during an ethical dilemma.[9]

Table 6.3b. Using the Nursing Process in Ethical Situations[10]

| Nursing Process Stage | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Assessment/Data Collection |

|

| Assessment/Analysis |

|

| Diagnosis |

|

| Outcome Identification |

|

| Planning |

|

| Implementation |

|

| Evaluation |

|

Four-Quadrant Approach

The four-quadrant approach integrates ethical principles (e.g., beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice) in conjunction with health care indications, individual and family preferences, quality of life, and contextual features.[11] See Table 6.3c for sample questions used during the four-quadrant approach.

Table 6.3c. Four-Quadrant Approach[12]

| Health Care Indications

(Beneficence and Nonmaleficence)

|

Individual and Family Preferences

(Respect for Autonomy)

|

| Quality of Life

(Beneficence, Nonmaleficence, and Respect for Autonomy)

|

Contextual Features

(Justice and Fairness)

|

MORAL Model

The MORAL model is a nurse-generated, decision-making model originating from research on nursing-specific moral dilemmas involving client autonomy, quality of life, distributing resources, and maintaining professional standards. The model provides guidance for nurses to systematically analyze and address real-life ethical dilemmas. The steps in the process may be remembered by using the mnemonic MORAL. See Table 6.3d for a description of each step of the MORAL model.[13],[14]

Table 6.3d. MORAL Model

| M: Massage the dilemma | Collect data by identifying the interests and perceptions of those involved, defining the dilemma, and describing conflicts. Establish a goal. |

|---|---|

| O: Outline options | Generate several effective alternatives to reach the goal. |

| R: Review criteria and resolve | Identify moral criteria and select the course of action. |

| A: Affirm position and act | Implement action based on knowledge from the previous steps (M-O-R). |

| L: Look back | Evaluate each step and the decision made. |

PLUS Ethical Decision-Making Model

The PLUS Ethical Decision-Making model was created by the Ethics and Compliance Initiative to help organizations empower employees to make ethical decisions in the workplace. This model uses four filters throughout the ethical decision-making process, referred to by the mnemonic PLUS:

- P: Policies, procedures, and guidelines of an organization

- L: Laws and regulations

- U: Universal values and principles of an organization

- S: Self-identification of what is good, right, fair, and equitable[15]

The seven steps of the PLUS Ethical Decision-Making model are as follows[16]:

- Define the problem using PLUS filters

- Seek relevant assistance, guidance, and support

- Identify available alternatives

- Evaluate the alternatives using PLUS to identify their impact

- Make the decision

- Implement the decision

- Evaluate the decision using PLUS filters

Media Attributions

- Moral Courage

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association (ANA). Ethics topics and articles. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/ethics-topics-and-articles/ ↵

- “Moral courage.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Norman, S. & Maguen, S. (n.d.). Moral injury. PTSD: National Center for PTSD, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/cooccurring/moral_injury.asp ↵

- Dean, W., Jacobs, B., & Manfredi, R. A. (2020). Moral injury: The invisible epidemic in COVID health care workers. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 76(4), 385–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.05.023 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Crisham, P. (1985). Moral: How can I do what is right? Nursing Management, 16(3), 44. https://journals.lww.com/nursingmanagement/citation/1985/03000/moral__how_can_i_do_what_s_right_.6.aspx ↵

- Ethics & Compliance Initiative. (2021). The PLUS Ethical Decision Making Model. https://www.ethics.org/resources/free-toolkit/decision-making-model/ ↵

- Ethics & Compliance Initiative. (2021). The PLUS Ethical Decision Making Model. https://www.ethics.org/resources/free-toolkit/decision-making-model/ ↵

Learning Objectives

- Identify safety considerations for adults of all ages

- Indicate correct identification of client prior to performing any client care measures

- Describe industry standards and regulations regarding microbiological, physical, and environmental safety

- Differentiate safety considerations among diverse clients

- Apply decision-making related to measures to minimize use of restraints

A national focus on reducing medical errors has been in place since 1999 when the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a report titled To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. This historic report broke the silence surrounding health care errors and encouraged safety to be built into the processes of providing client care. It was soon followed by the establishment of several safety initiatives by The Joint Commission, including the release of annual National Patient Safety Goals. Additionally, the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) Institute was developed to promote emphasis on high-quality, safe client care in nursing. This chapter will discuss several safety initiatives that promote a safe health care environment.

Safety: A Basic Need

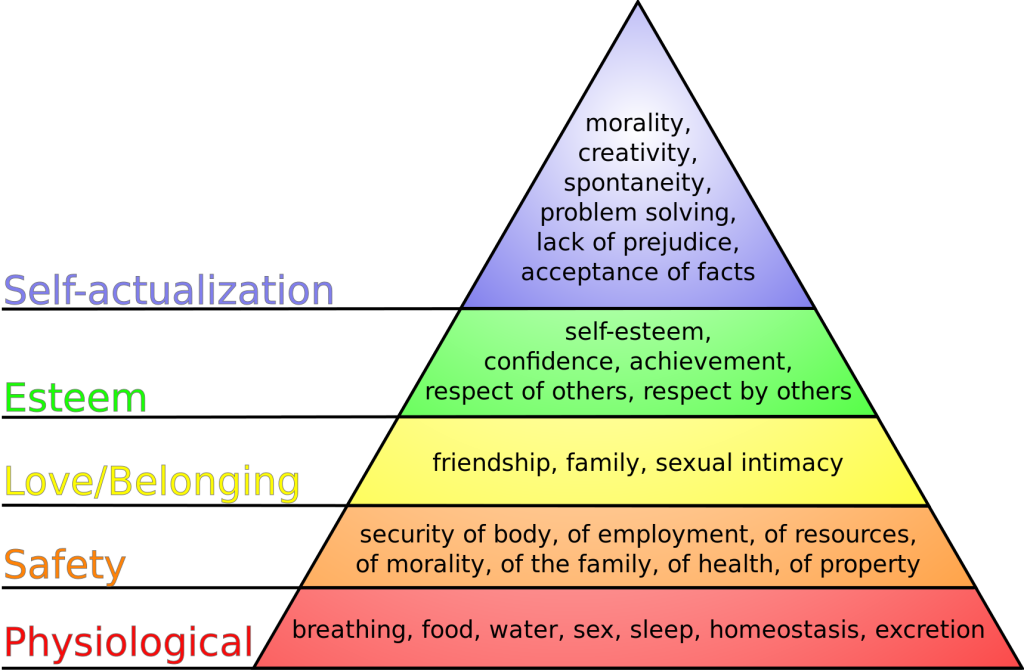

Safety is a basic foundational human need and always receives priority in client care. Nurses typically use Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to prioritize urgent client needs, with the bottom two rows of the pyramid receiving top priority. See Figure 5.1[1] for an image of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Safety is intertwined with basic physiological needs.

Consider the following scenario: You are driving back from a relaxing weekend at the lake and come upon a fiery car crash. You run over to the car to help anyone inside. When you get to the scene, you notice that the lone person in the car is not breathing. Your first priority is not to initiate rescue breathing inside the burning car, but to move the person to a safe place where you can safely provide CPR.

In nursing, the concept of client safety is central to everything we do in all health care settings. As a nurse, you play a critical role in promoting client safety while providing care. You also teach clients and their caregivers how to prevent injuries and remain safe in their homes and in the community. Safe client care also includes measures to keep you safe in the health care environment; if you become ill or injured, you will not be able to effectively care for others.

Safe client care is a commitment to providing the best possible care to every client and their caregivers in every moment of every day. Clients come to health care facilities expecting to be kept safe while they are treated for illnesses and injuries. Unfortunately, you may have heard stories about situations when that did not happen. Medical errors can be devastating to clients and their families. Consider the true story in the following box that illustrates factors affecting client safety.

The Josie King Story

In 2001, 18-month-old Josie King died as a result of medical errors in a well-known hospital from a hospital-acquired infection and an incorrectly administered pain medication. How did this preventable death happen? Watch this video of her mother, Sorrel King, telling Josie’s story and explaining how Josie’s death spurred her work on improving client safety in hospitals everywhere.[2]

Reflective Questions:

- What factors contributed to Josie’s death?

- How could these factors be resolved?

Never Events

The event described in the Josie King story is considered a “never event.” Never events are adverse events that are clearly identifiable, measurable, serious (resulting in death or significant disability), and preventable. In 2007 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) discontinued payment for costs associated with never events, and this policy has been adopted by most private insurance companies. Never events are publicly reported, with the goal of increasing accountability by health care agencies and improving the quality of client care. The current list of never events includes seven categories of events:

- Surgical or procedural event, such as surgery performed on the wrong body part

- Product or device, such as injury or death from a contaminated drug or device

- Client protection, such as client suicide in a health care setting

- Care management, such as death or injury from a medication error

- Environmental, such as death or injury as the result of using restraints

- Radiologic, such as a metallic object in an MRI area

- Criminal, such as death or injury of a client or staff member resulting from physical assault on the grounds of a health care setting

Sentinel Events

Sentinel events are very similar to never events although they may not be entirely preventable. They are defined by The Joint Commission as an “A client safety event that reaches a client and results in death, permanent harm, or severe temporary harm requiring interventions to sustain life." Such events are called "sentinel" because they signal the need for immediate investigation and response. Each accredited organization is strongly encouraged, but not required, to report sentinel events to The Joint Commission.[3] It is helpful to facilities to self-report sentinel events so that other facilities can learn from these events and future sentinel events can be prevented through knowledge sharing and risk reduction. Investigations into sentinel events are typically achieved through a process called root cause analysis.

Root cause analysis is a structured method used to analyze serious adverse events to identify underlying problems that increase the likelihood of errors, while avoiding the trap of focusing on mistakes by individuals. A multidisciplinary team analyzes the sequence of events leading up to the error with the goal of identifying how and why the event occurred. The ultimate goal of root cause analysis is to prevent future harm by eliminating hidden problems within a health care system that contribute to adverse events. For example, when a medication error occurs, a root cause analysis goes beyond focusing on the mistake by the nurse and looks at other system factors that contributed to the error, such as similar-looking drug labels, placement of similar-looking medications next to each other in a medication dispensing machine, or vague instructions in a provider order.

Root cause analysis uses human factors science as part of the investigation. Human factors focus on the interrelationships among humans, the tools and equipment they use in the workplace, and the environment in which they work. Safety in health care is ultimately dependent on humans - the doctors, nurses, and health care professionals - providing the care.

Near Misses

In addition to investigating sentinel events and never events, agencies use root cause analysis to investigate near misses. Near misses are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as, “An error that has the potential to cause an adverse event (client harm) but fails to do so because of chance or because it is intercepted.” Errors and near misses are rarely the result of poor motivation or incompetence of the health care professional but are often caused by key contributing factors such as poor communication, less-than-optimal teamwork, memory overload, reliance on memory for complex procedures, and lack of standardization of policies and procedures. In an effort to prevent near misses, medical errors, sentinel events, and never events, several safety strategies have been developed and implemented in health care organizations across the country. These strategies will be discussed throughout the remainder of the chapter.

Incident Reports and Client Safety

Recall from the previous discussion in Chapter 2.5 that an incident report is a specific type of documentation performed when there is an error, near miss, or other unexpected occurrence that occurs during client care. Incident reports are used to identify process problems or other areas that could benefit from safety and quality improvement and are not included in the client's medical record. They are a component of an agency's culture of safety and are used during investigations like root cause analysis to help improve the safety and quality of client care.

Safety strategies have been developed based on research to reduce the likelihood of errors and to create safe standards of care. Examples of safety initiatives include strategies to prevent medication errors, standardized checklists, and structured team communication tools.

Medication Errors

Several initiatives have been developed nationally to prevent medication errors, such as the establishment of a “Do Not Use List of Abbreviations," a “List of Error-Prone Abbreviations,” “Frequently Confused Medication List,” “High-Alert Medications List,” and the “Do Not Crush List.” Additionally, it is considered a standard of care for nurses to perform three checks of the rights of medication administration whenever administering medication. View more information about these safety initiatives to prevent medication errors in the box below. Specific strategies to prevent medication errors are discussed in the “Preventing Medication Errors” of the “Legal/Ethical” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e textbook. The rights of medication administration are discussed in the “Basic Concepts of Administering Medications” section of the “Administration of Enteral Medications” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e textbook.

Read more about safety initiatives implemented to prevent medication errors:

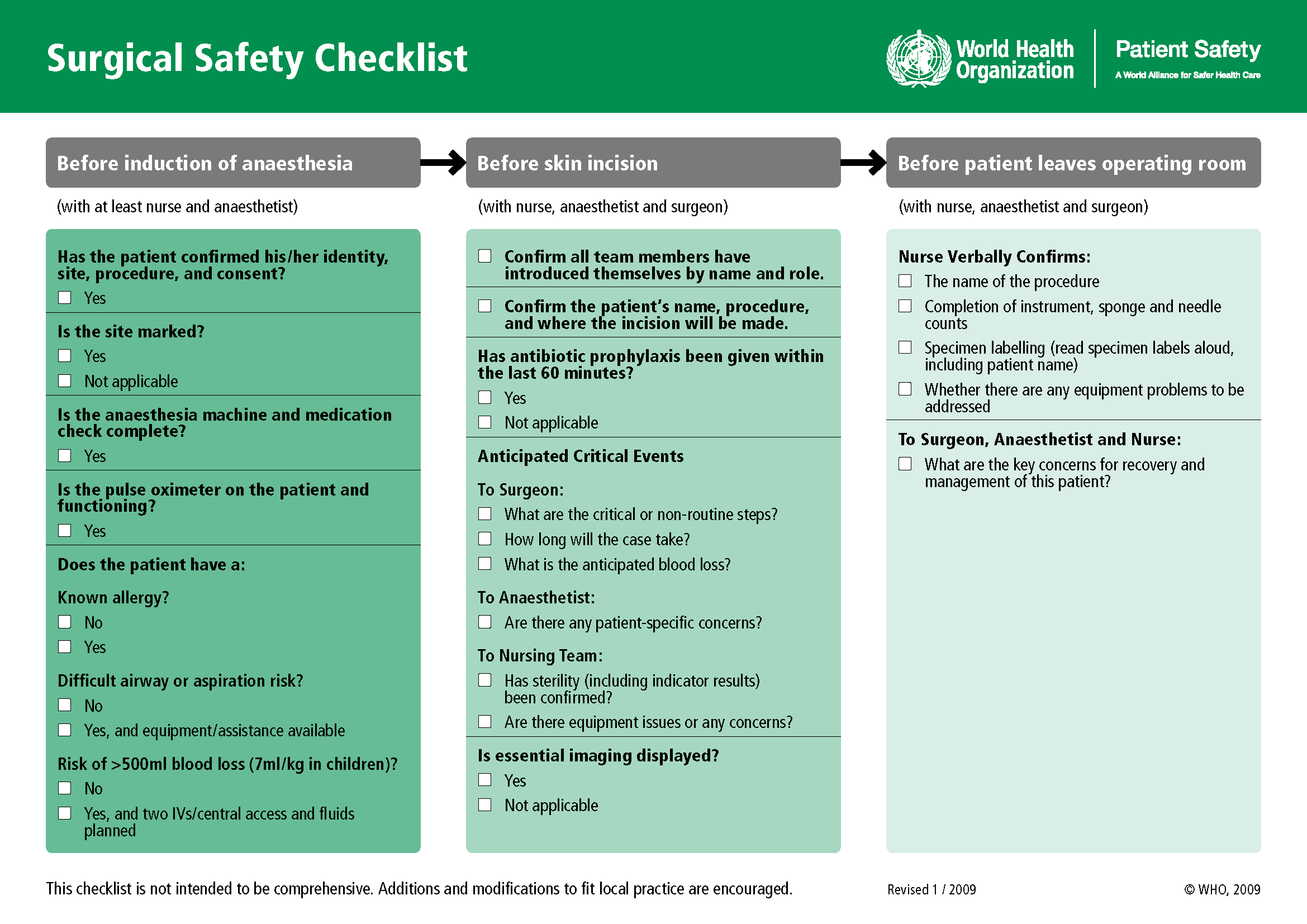

Checklists

Performance of complex medical procedures is often based on memory, even though humans are prone to short-term memory loss, especially when we are multitasking or under stress. The point-of-care checklist is an example of a client care safety initiative that reduces this reliance on fallible memory. For example, a surgical checklist developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) has been adopted by most surgical providers around the world as a standard of care. It has significantly decreased injuries and deaths caused by surgeries by focusing on teamwork and communication. The Association of PeriOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) combined recommendations from The Joint Commission and the WHO to create a specific surgical checklist for nurses. See Figure 5.2[4] for an image of the WHO surgical checklist.

View an example of a Preop Checklist in the "Preoperative Care" section of the "Perioperative" chapter of Open RN Nursing Health Alterations.

Team Communication

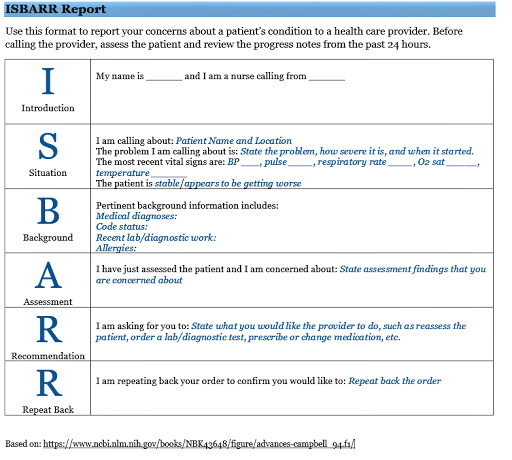

Nurses routinely communicate with multidisciplinary health care team members and contact health care providers to report changes in client status. Serious client harm can occur when client information is absent, incomplete, erroneous, or delayed during team communication. Standardized methods of communication are used to ensure that accurate information is exchanged among team members in a structured and concise manner, such as ISBARR reports and handoff reports.

ISBARR is a mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back. See Figure 5.3[5] for an image of an ISBARR reference card.

Handoff reports are a specific type of team communication as client care is transferred. Handoff reports are defined by The Joint Commission as, “A transfer and acceptance of client care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing client specific information from one caregiver to another, or from one team of caregivers to another, for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the client’s care.”[6]

Review information about ISBARR and handoff reports in Chapter 2.4.

In addition to implementing safety strategies to improve safe client care, leaders of a health care agency must also establish a culture of safety. A culture of safety reflects the behaviors, beliefs, and values within and across all levels of an organization as they relate to safety and clinical excellence, with a focus on people. In 2021 The Joint Commission released a sentinel event regarding the essential role of leadership in establishing a culture of safety. According to The Joint Commission, leadership has an obligation to be accountable for protecting the safety of all health care consumers, including clients, employees, and visitors. Without adequate leadership and an effective culture of safety, there is higher risk for adverse events. Inadequate leadership can contribute to adverse effects in a variety of ways, including, but not limited to, the following[7]:

- Insufficient support of client safety event reporting

- Lack of feedback or response to staff and others who report safety vulnerabilities

- Allowing intimidation of staff who report events

- Refusing to consistently prioritize and implement safety recommendations

- Not addressing staff burnout

Three components of a culture of safety are the following[8]:

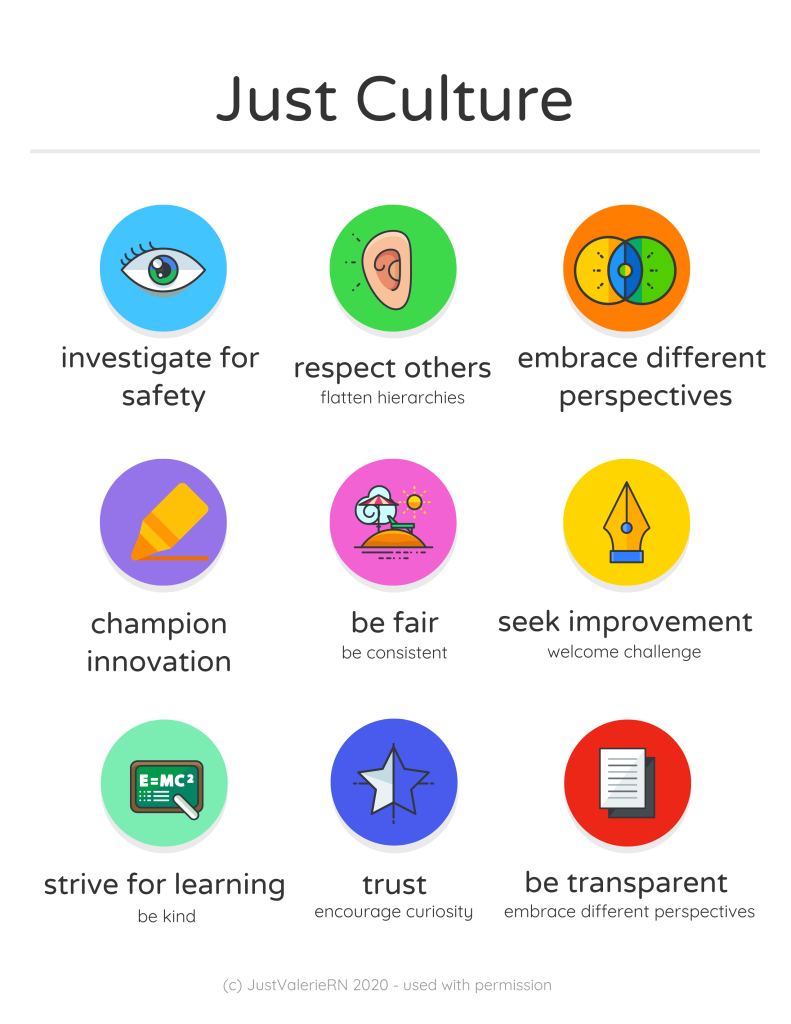

- Just Culture: People are encouraged, even rewarded, for providing essential safety-related information, but clear lines are drawn between human error and at-risk or reckless behaviors.

- Reporting Culture: People report errors and near-misses.

- Learning Culture: The willingness and the competence to draw the right conclusions from safety information systems, and the will to implement major reforms when their need is indicated.

The American Nurses Association further describes a culture of safety as one that includes openness and mutual respect when discussing safety concerns and solutions without shifting to individual blame, a learning environment with transparency and accountability, and reliable teams. In contrast, complexity, lack of clear measures, hierarchical authority, the “blame game,” and lack of leadership are examples of barriers that do not promote a culture of safety. If staff fear reprisal for mistakes and errors, they will be less likely to report errors, processes will not be improved, and client safety will continue to be impaired. See the following box for an example of safety themes established during a health care institution’s implementation of a culture of safety.

Safety Themes in a Culture of Safety[9]

Kaiser Permantente implemented a culture of safety in 2001 that focused on instituting the following six strategic themes:

- Safe culture: Creating and maintaining a strong safety culture, with client safety and error reduction embraced as shared organizational values.

- Safe care: Ensuring that the actual and potential hazards associated with high-risk procedures, processes, and client care populations are identified, assessed, and managed in a way that demonstrates continuous improvement and ultimately ensures that clients are free from accidental injury or illness.

- Safe staff: Ensuring that staff possess the knowledge and competence to perform required duties safely and contribute to improving system safety performance.

- Safe support systems: Identifying, implementing, and maintaining support systems—including knowledge-sharing networks and systems for responsible reporting—that provide the right information to the right people at the right time.

- Safe place: Designing, constructing, operating, and maintaining the environment of health care to enhance its efficiency and effectiveness.

- Safe clients: Engaging clients and their families in reducing medical errors, improving overall system safety performance, and maintaining trust and respect.

A strong safety culture encourages all members of the health care team to identify and reduce risks to client safety by reporting errors and near misses so that root cause analysis can be performed and identified risks are removed from the system. However, in a poorly defined and implemented culture of safety, staff often conceal errors due to fear or shame. Nurses have been traditionally trained to believe that clinical perfection is attainable, and that “good” nurses do not make errors. Errors are perceived as being caused by carelessness, inattention, indifference, or uninformed decisions. Although expecting high standards of performance is appropriate and desirable, it can become counterproductive if it creates an expectation of perfection that impacts the reporting of errors and near misses. If employees feel shame when they make an error, they may feel pressure to hide or cover up errors. Evidence indicates that approximately three of every four errors are detected by those committing them, as opposed to being detected by an environmental cue or another person. Therefore, employees need to be able to trust that they can fully report errors without fear of being wrongfully blamed. This provides the agency with the opportunity to learn how to further improve processes and prevent future errors from occurring. For many organizations, the largest barrier in establishing a culture of safety is the establishment of trust. A model called “Just Culture” has successfully been implemented in many agencies to decrease the “blame game,” promote trust, and improve the reporting of errors.

Just Culture

The American Nurses Association (ANA) officially endorses the Just Culture model. In 2019 the ANA published a position statement on Just Culture, stating, “Traditionally, healthcare’s culture has held individuals accountable for all errors or mishaps that befall clients under their care. By contrast, a Just Culture recognizes that individual practitioners should not be held accountable for system failings over which they have no control. A Just Culture also recognizes many individual or ‘active’ errors represent predictable interactions between human operators and the systems in which they work. However, in contrast to a culture that touts ‘no blame’ as its governing principle, a Just Culture does not tolerate conscious disregard of clear risks to clients or gross misconduct (e.g., falsifying a record or performing professional duties while intoxicated).”

The Just Culture model categorizes human behavior into three causes of errors. Consequences of errors are based on whether the error is a simple human error or caused by at-risk or reckless behavior.

- Simple human error: A simple human error occurs when an individual inadvertently does something other than what should have been done. Most medical errors are the result of human error due to poor processes, programs, education, environmental issues, or situations. These errors are managed by correcting the cause, looking at the process, and fixing the deviation. For example, a nurse appropriately checks the rights of medication administration three times, but due to the similar appearance and names of two different medications stored next to each other in the medication dispensing system, administers the incorrect medication to a client. In this example, a root cause analysis reveals a system issue that must be modified to prevent future errors (e.g., change the labelling and storage of look alike-sound alike medication).

- At-risk behavior: An error due to at-risk behavior occurs when a behavioral choice is made that increases risk where the risk is not recognized or is mistakenly believed to be justified. For example, a nurse scans a client’s medication with a barcode scanner prior to administration, but an error message appears on the scanner. The nurse mistakenly interprets the error to be a technology problem and proceeds to administer the medication instead of stopping the process and further investigating the error message, resulting in the wrong dosage of a medication being administered to the client. In this case, ignoring the error message on the scanner can be considered “at-risk behavior” because the behavioral choice was considered justified by the nurse at the time.

- Reckless behavior: Reckless behavior is an error that occurs when an action is taken with conscious disregard for a substantial and unjustifiable risk.[10] For example, a nurse arrives at work intoxicated and administers the wrong medication to the wrong client. This error is considered due to reckless behavior because the decision to arrive intoxicated was made with conscious disregard for substantial risk.

These examples show three different causes of medication errors that would result in different consequences to the employee based on the Just Culture model. Under the Just Culture model, after root cause analysis is completed, system-wide changes are made to decrease factors that contributed to the error. Managers appropriately hold individuals accountable for errors if they were due to simple human error, at-risk behavior, or reckless behaviors.

If an individual commits a simple human error, managers console the individual and consider changes in training, procedures, and processes. In the “simple human error” above, system-wide changes would be made to change the label and location of the medication to prevent future errors from occurring with the same medication.

Individuals committing at-risk behavior are held accountable for their behavioral choice and often require coaching with incentives for less risky behaviors and situational awareness. In the “at-risk behavior” example above where the nurse ignored an error message on the barcode scanner, mandatory training on using a barcode scanner and responding to errors would be implemented, and the manager would track the employee’s correct usage of the barcode scanner for several months following training.

If an individual demonstrates reckless behavior, remedial action and/or punitive action is taken.[11] In the “reckless behavior” example above, the manager would report the nurse’s behavior to the state's Board of Nursing with mandatory substance abuse counseling to maintain their nursing license. Employment may be terminated with consideration of patterns of behavior.

A Just Culture in which employees aren't afraid to report errors is a highly successful way to enhance client safety, increase staff and client satisfaction, and improve outcomes. Success is achieved through good communication, effective management of resources, and an openness to changing processes to ensure the safety of clients and employees. The infographic in Figure 5.4[12] illustrates the components of a culture of safety and Just Culture.

The principles of culture of safety, including Just Culture, Reporting Culture, and Learning Culture are also being adopted in nursing education. It’s understood that mistakes are part of learning and that a shared accountability model promotes individual- and system-level learning for improved client safety. Under a shared accountability model, students are responsible for the following[13]:

- Being fully prepared for clinical experiences, including laboratory and simulation assignments

- Being rested and mentally ready for a challenging learning environment

- Accepting accountability for their part in contributing to a safe learning environment

- Behaving professionally

- Reporting their own errors and near mistakes

- Keeping up-to-date with current evidence-based practice

- Adhering to ethical and legal standards

Students know they will be held accountable for their actions, but will not be blamed for system faults that lie beyond their control. They can trust that a fair process will be used to determine what went wrong if a client care error or near miss occurs. Student errors and near misses are addressed based on an investigation determining if it was simple human error, an at-risk behavior, or reckless behavior. For example, a simple human error by a student can be addressed with coaching and additional learning opportunities to remedy the knowledge deficit. However, if a student acts with recklessness (for example, repeatedly arrives to clinical unprepared despite previous faculty feedback or falsely documents an assessment or procedure), they are appropriately and fairly disciplined, which may include dismissal from the program.[14]

Every year, national safety goals are published by The Joint Commission to improve clientsafety. National Patient Safety Goals are goals and recommendations tailored to seven different types of health care agencies based on client safety data from experts and stakeholders. The seven health care areas include ambulatory health care settings, behavioral health care settings, critical access hospitals, home care, hospital settings, laboratories, nursing care centers, and office-based surgery settings. These goals are updated annually based on safety data and include evidence-based interventions. It is important for nurses and nursing students to be aware of the current National Patient Safety Goals for the settings in which they provide client care and use the associated recommendations.

The National Patient Safety Goals for nursing care settings (otherwise known as long-term care centers) are described in Table 5.5. (Note that the term “bedsore” is used in the last goal. This is a historic term for the current term “pressure injuries.”)

Table 5.5 National Patient Safety Goals for Nursing Care Centers[15]

| Goal | Recommendations and Rationale |

|---|---|

| Identify residents correctly | Use at least two ways to identify clients. For example, use the client’s or resident’s name and date of birth. This is done to make sure that each client gets the correct medication and treatment. |

| Use medicines safely | Take extra care with clients who take medications to thin their blood.

Record and pass along correct information about a client’s medications. Find out what medications the client is taking. Compare those medications to new medications prescribed for the client. Give the client written information about the medications they need to take. Tell the client it is important to bring their up-to-date list of medications every time they visit a doctor. |

| Prevent infection | Use the hand hygiene guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the World Health Organization. Set goals for improving hand cleaning. |

| Prevent residents from falling | Find out which clients are most likely to fall. For example, is the client taking any medications that might make them weak, dizzy, or sleepy? Implement fall precautions for these clients. |

| Prevent bed sores | Find out which clients are most likely to have bed sores (i.e., pressure injuries). Take action to prevent pressure injuries in these clients at risk. Per agency protocol, frequently assess clients for pressure injuries. |

Read more about National Patient Safety Goals established by The Joint Commission.

Read more details about how to identify clients correctly, administer medications safely, and prevent infection by visiting the following sections in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e:

- Initiating Patient Interaction

- Aseptic Technique Basic Concepts

- Basic Concepts of Administering Medications

Read more about "Pressure Injuries" (the current term used for "bed sores") in the "Integumentary" chapter of this book.

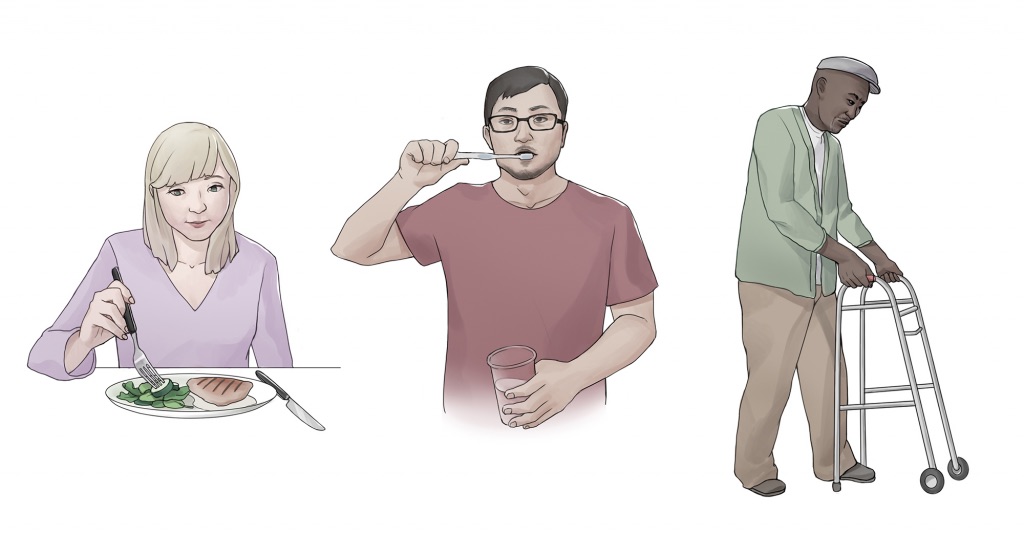

Functional health assessment collects data related to the patient’s functioning and their physical and mental capacity to participate in Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs). Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) are daily basic tasks that are fundamental to everyday functioning (e.g., hygiene, elimination, dressing, eating, ambulating/moving). See Figure 2.2[16] for an illustration of ADLs.

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) are more complex daily tasks that allow patients to function independently such as managing finances, paying bills, purchasing and preparing meals, managing one’s household, taking medications, and facilitating transportation. See Figure 2.3[17] for an illustration of IADLs. Assessment of IADLs is particularly important to inquire about with young adults who have just moved into their first place, as well as with older patients with multiple medical conditions and/or disabilities.

Information obtained when assessing functional health provides the nurse a holistic view of a patient’s human response to illness and life conditions. It is helpful to use an assessment framework, such as Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns,[18] to organize interview questions according to evidence-based patterns of human responses. Using this framework provides the patient and their family members an opportunity to identify health-related concerns to the nurse that may require further in-depth assessment. It also verifies patient understanding of conditions so that misperceptions can be clarified. This framework includes the following categories:

- Nutritional-Metabolic: Food and fluid consumption relative to metabolic need

- Elimination: Excretion including bowel and bladder

- Activity-Exercise: Activity and exercise

- Sleep-Rest: Sleep and rest

- Cognitive-Perceptual: Cognition and perception

- Role-Relationship: Roles and relationships

- Sexuality-Reproductive: Sexuality and reproduction

- Coping-Stress Tolerance: Coping and effectiveness of managing stress

- Value-Belief: Values, beliefs, and goals that guide choices and decisions

- Self-Perception and Self-Concept: Self-concept and mood state[19]

- Health Perception-Health Management: A patient’s perception of their health and well-being and how it is managed. This is an umbrella category of all the categories above and underlies performing a health history.

The functional health section can be started by saying, “I would like to ask you some questions about factors that affect your ability to function in your day-to-day life. Feel free to share any health concerns that come to mind during this discussion.” Focused interview questions for each category are included in Table 2.8. Each category is further described below.

Nutrition

The nutritional category includes, but is not limited to, food and fluid intake, usual diet, financial ability to purchase food, time and knowledge to prepare meals, and appetite. This is also an opportune time to engage in health promotion discussions about healthy eating. Be aware of signs for malnutrition and obesity, especially if rapid and excessive weight loss or weight gain have occurred.

Life Span Considerations

When assessing nutritional status, the types of questions asked and the level of detail depend on the developmental age and health of the patient. Family members may also provide important information.

- Infants: Ask parents about using breast milk or formula, amount, frequency, supplements, problems, and introductions of new foods.

- Pregnant women: Include questions about the presence of nausea and vomiting and intake of folic acid, iron, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, and calcium.

- Older adults or patients with disabling illnesses: Inquire about the ability to purchase and cook their food, decreased sense of taste, ability to chew or swallow foods, loss of appetite, and enough fiber and nutrients.[20]

Elimination

Elimination refers to the removal of waste products through the urine and stool. Health care professionals refer to urinating as voiding and stool elimination as having a bowel movement. Familiar terminology may need to be used with patients, such as “pee” and “poop.”

Constipation commonly occurs in hospitalized patients, so it is important to assess the date of their last bowel movement and monitor the frequency, color, and consistency of their stool.

Assess urine concentration, frequency, and odor, especially if concerned about urinary tract infection or incontinence. Findings that require further investigation include dysuria (pain or difficulty upon urination), blood in the stool, melena (black, tarry stool), constipation, diarrhea, or excessive laxative use.[21]

Life Span Considerations

When assessing elimination, the types of questions asked and the level of detail depends on the developmental age and health of the patient.

Toddlers: Ask parents or guardians about toilet training. Toilet training takes several months, occurs in several stages, and varies from child to child. It is influenced by culture and depends on physical and emotional readiness, but most children are toilet trained between 18 months and three years.

Older Adults: Constipation and incontinence are common symptoms associated with aging. Additional focused questions may be required to further assess these issues.[22]

Mobility, Activity, and Exercise

Mobility refers to a patient’s ability to move around (e.g., sit up, sit down, stand up, walk). Activity and exercise refer to informal and/or formal activity (e.g., walking, swimming, yoga, strength training). In addition to assessing the amount of exercise, it is also important to assess activity because some people may not engage in exercise but have an active lifestyle (e.g., walk to school or work in a physically demanding job).

Findings that require further investigation include insufficient aerobic exercise and identified risks for falls.[23]

Life Span Considerations

Mobility and activity depend on developmental age and a patient’s health and illness status. With infants, it is important to assess their ability to meet specific developmental milestones at each well-baby visit. Mobility can become problematic for patients who are ill or are aging and can result in self-care deficits. Thus, it is important to assess how a patient’s mobility is affecting their ability to perform ADLs and IADLs.[24]

Sleep and Rest

The sleep and rest category refers to a patient’s pattern of rest and sleep and any associated routines or sleeping medications used. Although it varies for different people and their life circumstances, obtaining eight hours of sleep every night is a general guideline. Findings that require further investigation include disruptive sleep patterns and reliance on sleeping pills or other sedative medications.[25]

Life Span Considerations

Older Adults: Disruption in sleep patterns can be especially troublesome for older adults. Assessing sleep patterns and routines will contribute to collaborative interventions for improved rest.[26]

Cognitive and Perceptual

The cognitive and perceptual category focuses on a person’s ability to collect information from the environment and use it in reasoning and other thought processes. This category includes the following:

- Adequacy of vision, hearing, taste, touch, feeling, and smell

- Any assistive devices used

- Pain level and pain management

- Cognitive functional abilities, such as orientation, memory, reasoning, judgment, and decision-making[27]

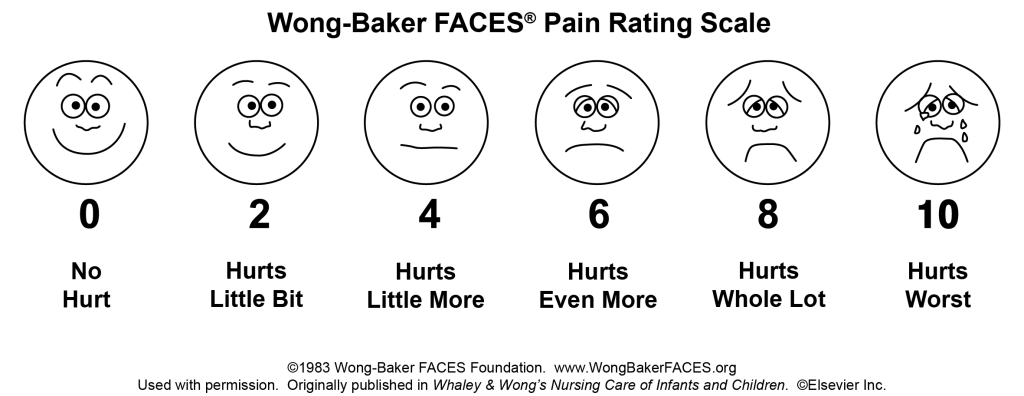

If a patient is experiencing pain, it is important to perform an in-depth assessment using the PQRSTU method described in the “Reason for Seeking Health Care” section of this chapter. It is also helpful to use evidence-based assessment tools when assessing pain, especially for patients who are unable to verbally describe the severity of their pain. See Figure 2.4[28] for an image of the Wong-Baker FACES tool that is commonly used in health care.

Life Span Considerations

Older Adults: Older adults are especially at risk for problems in the cognitive and perceptual category. Be alert for cues that suggest deficits are occurring that have not been previously diagnosed.

Roles - Relationships

Quality of life is greatly influenced by the roles and relationships established with family, friends, and the broader community. Roles often define our identity. For example, a patient may describe themselves as a “mother of an 8-year-old.” This category focuses on roles and relationships that may be influenced by health-related factors or may offer support during illness.[29] Findings that require further investigation include indications that a patient does not have any meaningful relationships or has “negative” or abusive relationships in their lives.

Life Span Considerations

Be sensitive to cues when assessing individuals with any of the following characteristics: isolation from family and friends during crisis, language barriers, loss of a significant person or pet, loss of job, significant home care needs, prolonged caregiving, history of abuse, history of substance abuse, or homelessness.[30]

Sexuality - Reproduction

Sexuality and sexual relations are an aspect of health that can be affected by illness, aging, and medication. This category includes a person’s gender identity and sexual orientation, as well as reproductive issues. It involves a combination of emotional connection, physical companionship (holding hands, hugging, kissing) and sexual activity that impact one’s feeling of health.[31]

The Joint Commission has defined terms to use when caring for diverse patients. Gender identity is a person’s basic sense of being male, female, or other gender.[32] Gender expression are characteristics in appearance, personality, and behavior that are culturally defined as masculine or feminine.[33] Sexual orientation is the preferred term used when referring to an individual’s physical and/or emotional attraction to the same and/or opposite gender.[34] LGBTQ is an acronym standing for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer population. It is an umbrella term that generally refers to a group of people who are diverse in gender identity and sexual orientation. It is important to provide a safe environment to discuss health issues because the LGBTQ population experiences higher rates of smoking, alcohol use, substance abuse, HIV and other STD infections, anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and attempts, and eating disorders as a result of stigma and marginalization.[35]

Life Span Considerations

Although sexuality is frequently portrayed in the media, individuals often consider these topics as private subjects. Use sensitivity when discussing these topics with different age groups across cultural beliefs while maintaining professional boundaries.

Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community.

Coping-Stress Tolerance

Individuals experience stress that can lead to dysfunction if not managed in a healthy manner. Throughout life, healthy and unhealthy coping strategies are learned. Coping strategies are behaviors used to manage anxiety. Effective strategies control anxiety and lead to problem-solving but ineffective strategies can lead to abuse of food, tobacco, alcohol, or drugs.[36] Nurses teach and reinforce effective coping strategies.

Substance Use and Abuse

Alcohol, tobacco products, marijuana, and drugs are often used as ineffective coping strategies. It is important to use a nonjudgmental approach when assessing a patient’s use of substances, so they do not feel stigmatized. Substance abuse can affect people of all ages. Make a distinction between use and abuse as you assess frequency of use and patterns of behavior. Substance abuse often causes disruption in everyday function (e.g., loss of employment, deterioration of relationships, or precarious living circumstances) because of dependence on a substance. Action is needed if patients indicate that they have a problem with substance use or show signs of dependence, addiction, or binge drinking.[37]

Life Span Considerations

Some individuals are at increased risk for problems with coping strategies and stress management. Be sensitive to cues when assessing individuals with characteristics such as uncertainty in medical diagnosis or prognosis, financial problems, marital problems, poor job fit, or few close friends and family members.[38]

Value-Belief

This category includes values and beliefs that guide decisions about health care and can also provide strength and comfort to individuals. It is common for a person’s spirituality and values to be influenced by religious faith. A value is an accepted principle or standard of an individual or group. A belief is something accepted as true with a sense of certainty. Spirituality is a way of living that comes from a set of values and beliefs that are important to a person. The Joint Commission asks health care professionals to respect patients’ cultural and personal values, beliefs, and preferences and accommodate patients’ rights to religious and other spiritual services.[39] When performing an assessment, use open-ended questions to allow the patient to share values and beliefs they believe are important. For example, ask, “I am interested in your spiritual and religious beliefs and how they relate to your health. Can you share with me any spiritual beliefs or religious practices that are important to you during your stay?”

Self-Perception and Self-Concept

The focus of this category is on the subjective thoughts, feelings, and attitudes of a patient about themself. Self-concept refers to all the knowledge a person has about themself that makes up who they are (i.e., their identity). Self-esteem refers to a person’s self-evaluation of these items as being worthy or unworthy. Body image is a mental picture of one’s body related to appearance and function. It is best to assess these items toward the end of the interview because you will have already collected data that contributes to an understanding of the patient’s self-concept. Factors that influence a patient’s self-concept vary from person to person and include elements of life they value, such as talents, education, accomplishments, family, friends, career, financial status, spirituality, and religion.[40] The self-perception and self-concept category also focuses on feelings and mood states such as happiness, anxiety, hope, power, anger, fear, depression, and control.[41]

Life Span Considerations

Some individuals are at risk for problems with self-perception and self-concept. Be sensitive to cues when assessing individuals with characteristics such as uncertainty regarding a medical diagnosis or surgery, significant personal loss, history of abuse or neglect, loss of body part or function, or history of substance abuse.[42]

Violence and Trauma

There are many types of violence that a person may experience, including neglect or physical, emotional, mental, sexual, or financial abuse. You are legally mandated to report suspected cases of child abuse or neglect, as well as suspected cases of elder abuse. At any time, if you or the patient is in immediate danger, follow agency policy and procedure.

Trauma results from violence or other distressing events in a life. Collaborative intervention with the patient is required when violence and trauma are identified. People respond in different ways to trauma. It is important to use a trauma-informed approach when caring for patients who have experienced trauma. For example, a patient may respond to the traumatic situation in a way that seems unfitting (such as with laughter, ambivalence, or denial). This does not mean the patient is lying but can be a symptom of trauma. To reduce the effects of trauma, it is important to implement collaborative interventions to support patients who have experienced trauma.[43]

Loss of Body Part

A person can have negative feelings or perceptions about the characteristics, function, or limits of a body part as a result of a medical condition, surgery, trauma, or mental condition. Pay attention to cues, such as neglect of a body part or negative comments about a body part and use open-ended questions to obtain additional information.

Mental Health

Mental health is frequently underscreened and unaddressed in health care. The mental health of all patients should be assessed, even if they appear well or state they have no mental health concerns so that any changes in condition are quickly noticed and treatment implemented. Mental health includes emotional and psychological symptoms that can affect a patient's day-to-day ability to function. The World Health Organization (2014) defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes their own potential, can cope with normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to their community.”[44] Mental illness includes conditions diagnosed by a health care provider, such as depression, anxiety, addiction, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and others. Mental illness can disrupt everyday functioning and affect a person’s employment, education, and relationships.

It is helpful to begin this component of a mental health assessment with a statement such as, “Mental health is an important part of our lives, so I ask all patients about their mental health and any concerns or questions they may have.”[45] Be attentive of critical findings that require intervention. For example, if a patient talks about feeling hopeless or depressed, it is important to screen for suicidal thinking. Begin with an open-ended question, such as, “Have you ever felt like hurting yourself?” If the patient responds with a “Yes,” then progress with specific questions that assess the immediacy and the intensity of the feelings. For example, you may say, “Tell me more about that feeling. Have you been thinking about hurting yourself today? Have you put together a plan to hurt yourself?” When assessing for suicidal thinking, be aware that a patient most at risk is someone who has a specific plan about self-harm and can specify how and when they will do it. They are particularly at risk if planning self-harm within the next 48 hours. The age of the patient is not a factor in this determination of risk. If you believe the patient is at high risk, do not leave the patient alone. Collaborate with them regarding an immediate plan for emergency care.[46]

Health Perception-Health Management

Health perception-health management is an umbrella term encompassing all of the categories described above, as well as environmental health.

Environmental Health

Environmental health refers to the safety of a patient’s physical environment, also called a social determinant of health. Examples of environmental health include, but are not limited to, exposure to violence in the home or community; air pollution; and availability of grocery stores, health care providers, and public transportation. Findings that require further investigation include a patient living in unsafe environments.[47]

See Table 2.8 for sample focused questions for all categories related to functional health.[48]

Table 2.8 Focused Interview Questions for Functional Health Categories[49]

Begin this section by saying, "I would like to ask you some questions about factors that affect your ability to function in your day-to-day life. Feel free to share any health concerns that come to mind during this discussion.”

| Category | Focused Questions |

|---|---|

| Nutrition | Tell me about your diet.

What foods do you usually eat? What fluids do you usually drink every day? What have you eaten in the last 24 hours? Is this typical of your usual eating pattern? Tell me about your appetite. Have you had any changes in your appetite? Do you have any goals related to your nutrition? Do you have any financial concerns about purchasing food? Are you able to prepare the meals you want to eat? |

| Elimination | When was your last bowel movement?

Do you have any problems with constipation, diarrhea, or incontinence? Do you take laxatives or stool softeners? Do you have any problems urinating, such as frequent urination or burning on urination? Do you ever experience leaking or dribbling of urine? |

| Mobility, Activity, and Exercise | Tell me about your ability to move around.

Do you have any problems sitting up, standing up, or walking? Do you use any mobility aids (e.g., cane, walker, wheelchair)? Tell me about the activity and/or exercise in which you engage. What type? How frequent? For how long? |

| Sleep and Rest | Tell me about your sleep routine. How many hours of sleep do you usually get?

Do you feel rested when you awaken? Do you do anything to wind down before you go to bed (e.g., watch TV, read)? Do you take any sleeping medication? Do you take any naps during the day? |

| Cognitive and Perceptual | Are you having any pain?

Note: If present, use the PQRSTU method to further assess pain. Are you having any issues with seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, or feeling things? Have you noticed any changes in memory or problems concentrating? Have you noticed any changes in the ability to make decisions? What is the easiest way for you to learn (e.g., written materials, explanations, or learning-by-doing)? |

| Roles and Relationships | Tell me about the most influential relationships in your life with family and friends.

How do these relationships influence your day-to-day life, health, and illness? Who are the people with whom you talk to when you require support or are struggling in your life? Do you have family or others dependent on you? Have you had any recent losses of someone important to you, a pet, or a job? Do you feel safe in your current relationship? |

| Sexuality-Reproduction | The expression of love and caring in a sexual relationship and creation of family are often important aspects in a person’s life. Do you have any concerns about your sexual health?

Tell me about the ways that you ensure your safety when engaging in intimate and sexual practices. |

| Coping-Stress | Tell me about the stress in your life.

Have you experienced a recent loss in your life that has impacted you? How do you cope with stress? |

| Values-Belief | I am interested in your spiritual and religious beliefs and how they relate to your health. Can you share with me any spiritual beliefs or religious practices that are important to you? |

| Self-Perception and Self-Concept |

Tell me what makes you who you are. How would you describe yourself? Have you noticed any changes in how you view your body or the things you can do? Are these a problem for you? Have you found yourself feeling sad, angry, fearful, or anxious? What helps you to feel better when this happens? Have you ever used any tobacco products (e.g., cigarettes, pipes, vaporizers, hookah)? If so, how much? How much alcohol do you drink every week? Have you used cannabis products? If so, how often do you use them? Have you ever used drugs or prescription drugs that were not prescribed for you? If so, what type? Have you ever felt you had a problem with any of these substances because they affected your daily life? If so, tell me more. Do you want to quit any of these substances? Many patients have experienced violence or trauma in their lives. Have you experienced any violence or trauma in your life? How has it affected you? Would you like to talk with someone about it?

|

| Health Perception - Health Management |

Tell me about how you take care of yourself and manage your home. Have you had any falls in the past six months? Do you have enough finances to pay your bills and purchase food, medications, and other needed items? Do you have any current or future concerns about being able to function independently? Tell me about where you live. Do you have any concerns about safety in your home or neighborhood? Tell me about any factors in your environment that may affect your health. Do you have any concerns about how your environment is affecting your health? |