Other Legal Issues

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

In addition to being aware of the legal and regulatory frameworks in which one practices nursing, it is also important for nurses to understand the legal concepts of informed consent and advance directives.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is the fundamental right of a client to accept or reject health care. Nurses have a legal responsibility to provide verbal and/or written information and obtain verbal or written consent for performing nursing care such as bathing, medication administration, and urinary or intravenous catheter insertion. While physicians have the responsibility to provide information and obtain informed consent related to medical procedures, nurses are typically required to verify the presence of a valid, signed informed consent before the procedure is performed. Additionally, if nurses do not believe the patient has adequate understanding of a procedure, its risks, benefits, or alternatives to treatment, they should request the provider return to clarify unclear information with the client. Nurses must remain within their scope of practice related to informed consent beyond nursing acts.

Two legal concepts related to informed consent are competence and capacity. Competence is a legal term defined as the ability of an individual to participate in legal proceedings. A judge decides if an individual is “competent” or “incompetent.” In contrast, capacity is “a functional determination that an individual is or is not capable of making a medical decision within a given situation.”[1] It is outside the scope of practice for nurses to formally assess capacity, but nurses may initiate the evaluation of client capacity and contribute assessment information. States typically require two health care providers to identify an individual as “incapacitated” and unable to make their own health care decisions. Capacity may be a temporary or permanent state.

The following box outlines situations where the nurse may question a client’s decision-making capacity.

| Triggers for Questioning Capacity and Decision-Making[2] |

|---|

|

If an individual has an advance directive in place, their designated power of attorney for health care may step in and make medical decisions when the client is deemed incapacitated. In the absence of advance directives, the legal system may take over and appoint a guardian to make medical decisions for an individual. The guardian is often a family member or friend but may be completely unrelated to the incapacitated individual. Nurses are instrumental in encouraging a client to complete an advance directive while they have capacity to do so.

Advance Directives

The Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA) is a federal law passed by Congress in 1990 following highly publicized cases involving the withdrawal of life-supporting care for incompetent individuals. (Read more about the Karen Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and Terri Shaivo cases in the boxes at the end of this section.) The PSDA requires health care institutions, such as hospitals and long-term care facilities, to offer adults written information that advises them “to make decisions concerning their medical care, including the right to accept or refuse medical or surgical treatment and the right to formulate, at the individual’s option, advance directives.”[3] Advanced directives are defined as written instructions, such as a living will or durable power of attorney for health care, recognized under state law, relating to the provision of health care when the individual is incapacitated. The PSDA allows clients to record their preferences about do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment. In the absence of a client’s advance directives, the court may assert an “unqualified interest in the preservation of human life to be weighed against the constitutionally protected interests of the individual.”[4] For this reason, nurses must educate and support the communities they serve regarding the creation of advanced directives.

Advanced directives vary by state. For example, some states allow lay witness signatures whereas some require a notary signature. Some states place restrictions on family members, doctors, or nurses serving as witnesses. It is important for individuals creating advance directives to follow instructions for state-specific documents to ensure they are legally binding and honored.

Advance directives do not require an attorney to complete. In many organizations, social workers or chaplains assist individuals to complete advance directives following referral from physicians or nurses. Clients should review and update their documents every 10-15 years, as well as with changes in relationship status or if new medical conditions are diagnosed.

Although advanced directive documents vary by state, they generally fall into two categories, referred to as a living will or durable power of attorney for healthcare.

Living Will

A living will is a type of advance directive in which an individual identifies what treatments they would like to receive or refuse if they become incapacitated and unable to make decisions. In most states, a living will only goes into effect if an individual meets specific medical criteria.[5] The living will often includes instructions regarding life-sustaining measures, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), mechanical ventilation, and tube feeding.

Durable Power of Attorney for Healthcare

It is impossible for an individual to document their preferences in a living will for every conceivable medical scenario that may occur. For this reason, it is essential for individuals to complete a durable power of attorney for healthcare. A durable power of attorney for healthcare (DPOAHC) is a person chosen to speak on one’s behalf if one becomes incapacitated. Typically, a primary health care power of attorney (POA) is identified with an alternative individual designated if the primary POA is unable or unwilling to do so. The health care POA is expected to make health care decisions for an individual they believe the person would make for themselves, based on wishes expressed in a living will or during previous conversations.[6]

It is essential for nurses to encourage clients to complete advance directives and have conversations with their designated POA about health care preferences, especially related to possible traumatic or end-of-life events that could require medical treatment decisions. Nurses can also dispel common misconceptions, such as these documents give the health care POA power to manage an individual’s finances. (A financial POA performs different functions than a health care POA and should be discussed with an attorney.)

After the advance directives are completed and included in the client’s medical record, the nurse has the responsibility to ensure they are appropriately incorporated into their care if they should become incapacitated.

View state-specific advance directives at the American Association of Retired Persons website.

Karen Ann Quinlan is an important figure in the United States’ history of defining life and death, a client’s privacy, and the state’s interest in preserving life and preventing murder. In April 1975, Karen Quinlan was 21 years old and became unresponsive after ingesting a combination of valium and alcohol while celebrating a friend’s birthday. She experienced respiratory failure, and although resuscitation efforts were successful, she suffered irreversible brain damage. She remained in a persistent vegetative state and became ventilator dependent. Her parents requested her physicians discontinue the ventilator because they believed it constituted extraordinary means to prolong her life. Her physicians denied their request out of concern of possible homicide charges based on New Jersey’s law. The Quinlans filed the first “right to die” lawsuit in September of 1975 but were denied by the New Jersey Superior Court in November. In March of 1976, the New Jersey Supreme Court determined the parent’s right to determine Karen’s medical treatment exceeded that of the state. Karen was discontinued from the ventilator six weeks later. When taken off the ventilator, Karen shocked many by continuing to breathe on her own. She lived in a coma for nine more years and succumbed to pneumonia on June 11, 1985.

-

- Sample Case: Nancy Beth Cruzan[8]

Nancy Cruzan is another important figure in the history of US “right to die” legal cases. At the age of 25, Nancy Cruzan was in a car accident on January 11, 1983. She never regained consciousness. After three years in a rehabilitation hospital, her parents began an eight-year battle in the courts to remove Nancy’s feeding tube. Nancy’s case was the first “right to die” case heard by the United States Supreme Court. Beyond allowing for the discontinuation of Nancy’s feeding tube, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that all adults have the right to the following:1) Choose or refuse any medical or surgical intervention, including artificial nutrition and hydration.

2) Make advance directives and name a surrogate to make decisions on their behalf.

3) Surrogates can decide on treatment options even when all concerned are aware that such measures will hasten death, as long as causing death is not their intent.Nancy died nine days after removal of her feeding tube in December 1990. As a result of the Cruzan decision, the Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA) was passed and took effect December 1, 1991. The act requires facilities to inform clients about their right to refuse treatment and to ask if they would like to prepare an advance directive.

- Sample Case: Nancy Beth Cruzan[8]

Sample Case: Terri Schaivo[9]

The Terri Schaivo case is a key case in history of advance directives in the United States because of its focus on the importance of having written advance directives to prevent family animosity, pain, and suffering. In 1990 Terri Schaivo was 26 years old. In her Florida home, she experienced a cardiac arrest thought to be a function of a low potassium level resulting from an eating disorder. She experienced severe anoxic brain injury and entered a persistent vegetative state. A PEG tube was inserted to provide medications, nutrition, and hydration. After three years, her husband refused further life-sustaining measures on her behalf, based on a statement Terri had once made, stating, “I don’t want to be kept alive on a machine.” He expressed interest in obtaining a DNR order, withholding antibiotics for a urinary tract infection, and ultimately requested removal of the PEG tube. However, Terri’s parents never accepted the diagnosis of persistent vegetative state and vigorously opposed their son-in-law’s decision and requests. Seven years of litigation generated 30 legal opinions, all supporting Michael Schiavo’s right to make a decision on his wife’s behalf. Terri died on March 31, 2005, following removal of her feeding tube.

- Darby, R. R., & Dickerson, B. C. (2017). Dementia, decision making, and capacity. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 25(6), 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000163 ↵

- American Nursing Association. (2010). Position statement: Just culture. https://www.nursingworld.org/~4afe07/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/health-and-safety/just_culture.pdf ↵

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). Part 489-Provider agreements and supplier approval, Subpart A-General provisions. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2012-title42-vol5/pdf/CFR-2012-title42-vol5-chapIV.pdf ↵

- Nurses Service Organization and CNA Financial. (2020, June). Nurse professional liability exposure claim report (4th ed.). https://www.nso.com/Learning/Artifacts/Claim-Reports/Minimizing-Risk-Achieving-Excellence ↵

- AARP. (2020, February 25). Advance directive forms. https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/financial-legal/free-printable-advance-directives/#more-advancedirectives ↵

- AARP. (2020, February 25). Advance directive forms. https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/financial-legal/free-printable-advance-directives/#more-advancedirectives ↵

- Arthur J. Morris Law Library. (n.d.). Karen Ann Quinlan and the right to die. https://archives.law.virginia.edu/dengrove/writeup/karen-ann-quinlan-and-right-die ↵

- Taub, S. (2001). Art of medicine “Departed, Jan 11, 1983; At Peace, Dec 26, 1990.” Virtual Mentor, American Medical Association Journal of Ethics, 3(7), 231-233. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/sites/journalofethics.ama-assn.org/files/2021-05/artm1-0107.pdf ↵

- Weijer, C. (2005). A death in the family: Reflections on the Terri Schiavo case. Canadian Medical Association Journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne, 172(9), 1197–1198. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050348 ↵

Before learning how to use the nursing process, it is important to understand basic concepts concerning how critical thinking relates to nursing practice. Let's take a deeper look at how nurses think.

Critical Thinking and Clinical Reasoning

Nurses make decisions while providing client care by using critical thinking and clinical reasoning. Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.”[1] Using critical thinking means that nurses take extra steps to maintain client safety and don’t just “follow orders.” It also means the accuracy of client information is validated and plans for caring for clients are based on their needs, current clinical practice, and research.

“Critical thinkers” possess certain attitudes that foster rational thinking. These attitudes are as follows:

- Independence of thought: Thinking on your own

- Fair-mindedness: Treating every viewpoint in an unbiased, unprejudiced way

- Insight into egocentricity and sociocentricity: Thinking of the greater good and not just thinking of yourself. Knowing when you are thinking of yourself (egocentricity) and when you are thinking or acting for the greater good (sociocentricity)

- Intellectual humility: Recognizing your intellectual limitations and abilities

- Nonjudgmental: Using professional ethical standards and not basing your judgments on your own personal or moral standards

- Integrity: Being honest and demonstrating strong moral principles

- Perseverance: Persisting in doing something despite it being difficult

- Confidence: Believing in yourself to complete a task or activity

- Interest in exploring thoughts and feelings: Wanting to explore different ways of knowing

- Curiosity: Asking “why” and wanting to know more

Clinical reasoning is defined as, “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze client information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.”[2] To make sound judgments about client care, nurses must generate alternatives, weigh them against the evidence, and choose the best course of action. The ability to clinically reason develops over time and is based on knowledge and experience.[3]

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning and Clinical Judgment

Inductive and deductive reasoning are important critical thinking skills. They help the nurse use clinical judgment when implementing the nursing process.

Inductive reasoning involves noticing cues, making generalizations, and creating hypotheses based on specific information or incidents. Cues are data that fall outside of expected findings that give the nurse a hint or indication of a client’s potential problem or condition. The nurse organizes these cues into patterns and creates a generalization. A generalization is a judgment formed from a set of facts, cues, and observations and is similar to gathering pieces of a jigsaw puzzle into patterns until the whole picture becomes more clear. Based on generalizations created from patterns of data, the nurse creates a hypothesis regarding a client problem. A hypothesis is a proposed explanation for a situation. It attempts to explain the “why” behind the problem that is occurring. If a “why” is identified, then a solution can begin to be explored.

No one can draw conclusions without first noticing cues. Paying close attention to a client, the environment, and interactions with family members is critical for inductive reasoning. As you work to improve your inductive reasoning, begin by first noticing details about the things around you. A nurse is similar to the detective looking for cues in Figure 4.1.[4] Be mindful of your five primary senses: the things that you hear, feel, smell, taste, and see. Nurses need strong inductive reasoning patterns and be able to take action quickly, especially in emergency situations. They can see how certain objects or events form a pattern (i.e., generalization) that indicates a common problem (i.e., hypothesis).

Example: A nurse assesses a client and finds the surgical incision site is red, warm, and tender to the touch. The nurse recognizes these cues form a pattern of signs of infection and creates a hypothesis that the incision has become infected. The provider is notified of the client’s change in condition, and a new prescription is received for an antibiotic. This is an example of the use of inductive reasoning in nursing practice.

Deductive reasoning is another type of critical thinking that is referred to as “top-down thinking.” Deductive reasoning relies on using a general standard or rule to create a strategy. Deductive reasoning relies on a general statement or hypothesis - sometimes called a premise or standard - that is held to be true. The premise is used to reach a specific, logical conclusion. Nurses use standards set by their state's Nurse Practice Act, federal regulations, the American Nursing Association, professional organizations, and their employer to make decisions about client care and solve problems.

Example: Based on research findings, hospital leaders determine clients recover more quickly if they receive adequate rest. The hospital creates a policy for quiet zones at night by initiating no overhead paging, promoting low-speaking voices by staff, and reducing lighting in the hallways. (See Figure 4.2).[5] The nurse further implements this policy by organizing care for clients that promotes periods of uninterrupted rest at night. This is an example of deductive thinking because the intervention is applied to all clients regardless if they have difficulty sleeping or not.

Clinical judgment is the result of critical thinking and clinical reasoning using inductive and deductive reasoning. Clinical judgment is defined by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) as, “The observed outcome of critical thinking and decision-making. It uses nursing knowledge to observe and assess presenting situations, identify a prioritized client concern, and generate the best possible evidence-based solutions in order to deliver safe client care.”[6] The NCSBN administers the national licensure exam (NCLEX) that evaluates the decision-making ability of nursing graduates and sets a minimum standard for safe, competent nursing care by entry-level licensed nurses. The NCLEX uses the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM) to measure clinical judgment.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is defined by the American Nurses Association (ANA) as, “A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health care consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and client, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.”[7]

Nursing Process

The nursing process is a critical thinking model based on a systematic approach to client-centered care. Nurses use the nursing process to perform clinical reasoning and make clinical judgments when providing client care. The nursing process is based on the Standards of Professional Nursing Practice established by the American Nurses Association (ANA). These standards are authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses (RNs), regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently.[8] The mnemonic ADOPIE is an easy way to remember the ANA Standards and the nursing process. Each letter refers to the six components of the nursing process: Assessment, Diagnosis, Outcomes Identification, Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation.

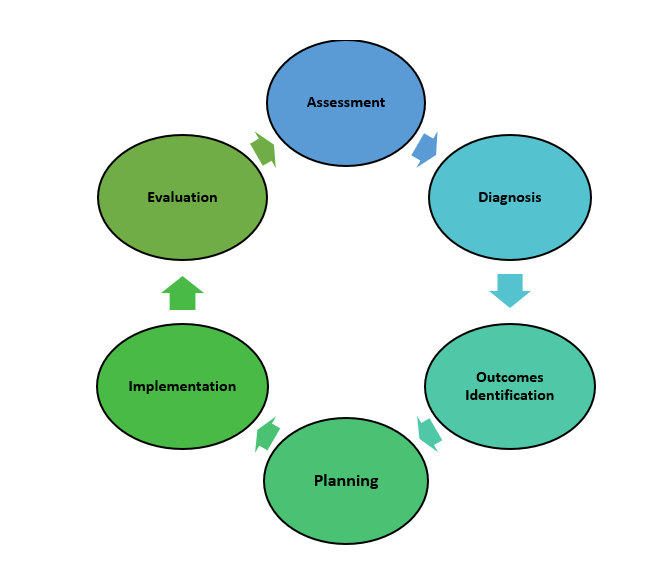

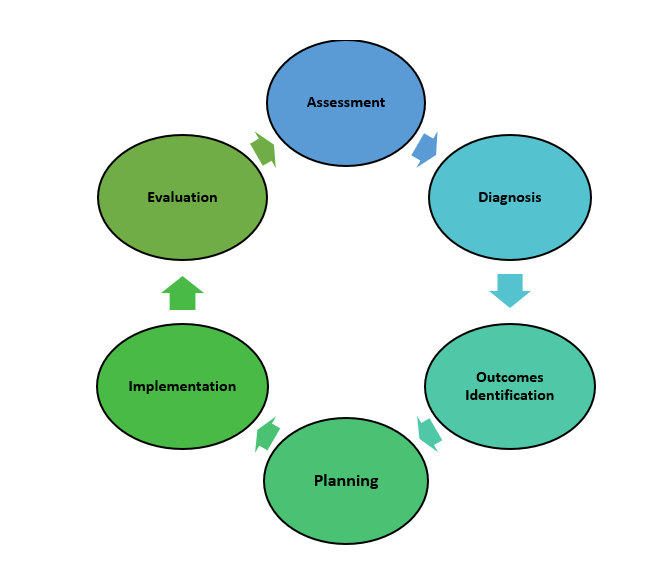

The nursing process is a continuous, cyclical process that is constantly adapting to the client’s current health status. See Figure 4.3[9] for an illustration of the nursing process.

The ANA's Standards of Professional Nursing Practice associated with each component of the nursing process are described below.

Assessment

The "Assessment" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse collects pertinent data and information relative to the health care consumer’s health or the situation.”[10] A registered nurse uses a systematic method to collect and analyze client data. Assessment includes physiological data, as well as psychological, sociocultural, spiritual, economic, and lifestyle data. For example, a nurse’s assessment of a hospitalized client in pain includes recognizing cues such as the client’s response to pain, such as the inability to get out of bed, refusal to eat, withdrawal from family members, or anger directed at hospital staff.[11]

Licensed practical/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs) assist with gathering data according to their state's scope of practice, but do not analyze data because this is outside their scope of practice. The "Assessment" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Assessment" section of this chapter.

Diagnosis

The "Diagnosis" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse analyzes the assessment data to determine actual or potential diagnoses, problems, and issues.”[12] A nursing diagnosis is the nurse’s clinical judgment about the response from the client to actual or potential health conditions or needs. Nursing diagnoses are the bases for the nurse’s care plan and are different than medical diagnoses.[13]

Analyzing assessment data and formulating a nursing diagnosis is outside the scope of practice for LPN/VNs, and as such, they do not assist with this phase of the nursing process. The "Diagnosis" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Diagnosis" section of this chapter.

Outcome Identification

The "Outcome Identification" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse identifies expected outcomes for a plan individualized to the health care consumer or the situation.”[14] The nurse sets measurable and achievable short- and long-term goals and specific outcomes in collaboration with the client based on their assessment data and nursing diagnoses.

Outcome identification is outside the scope of practice of LPN/VNs, and as such, they do not assist with this phase of the nursing process. The "Outcome Identification" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Outcome Identification" section of this chapter.

Planning

The "Planning" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse develops a collaborative plan encompassing strategies to achieve expected outcomes.”[15] Assessment data, diagnoses, and goals are used to select evidence-based nursing interventions customized to each client’s needs in order to achieve their previously established goals and outcomes. Nursing interventions are planned and documented by RNs in the client's nursing care plan so that nurses, as well as other health professionals, can refer to it for continuity of care.[16]

The "Planning" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Planning" section of this chapter.

Nursing Care Plans

Creating nursing care plans is a part of the "Planning" step of the nursing process. A nursing care plan is a type of documentation that demonstrates the individualized planning and delivery of nursing care for each specific client using the nursing process. RNs create nursing care plans so that the care provided to the client across shifts is consistent among health care personnel. Some interventions can be delegated to LPN/VNs or trained Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAPs) with RN supervision.

Creating the nursing care plan is outside the scope of practice, and as such, the LPN/VNs do not perform this task, although they may contribute to it. Developing nursing care plans and implementing appropriate delegation are further discussed under the “Planning” and “Implementation of Interventions” sections of this chapter.

Implementation

The "Implementation" Standard of Practice is defined as, "The nurse implements the identified plan.”[17] Nursing interventions are implemented or delegated with supervision according to the care plan to assure continuity of care across multiple nurses and health professionals caring for the client. Interventions are documented in the client’s electronic medical record as they are completed.[18] LPN/VNs implement interventions contained in the nursing care plan, provided they are within their scope of practice. The LPN/VN is responsible for documenting the interventions they perform in the client's medical record.

The "Implementation" Standard of Professional Practice also includes the subcategories "Coordination of Care" and "Health Teaching and Health Promotion" to promote health and a safe environment.[19]

The "Implementation" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Implementation of Interventions" section of this chapter.

Evaluation

The "Evaluation" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse evaluates progress toward attainment of goals and outcomes.”[20] During evaluation, nurses reassess the client and compare the findings against established outcomes to determine the effectiveness of the interventions and overall nursing care plan. During this phase, RNs ask, "Were outcomes met? Are any modifications required for the nursing care plan?" Both the client’s status and the effectiveness of the nursing care plan are continuously evaluated and modified as needed.[21]

Evaluating and modifying the nursing care plan is outside the scope of practice of LPN/VNs, although they can assist in gathering assessment data to assist the RN in performing this step of the nursing process. The "Evaluation" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Evaluation" section of this chapter.

Benefits of Using the Nursing Process

Using the nursing process has many benefits for nurses, clients, and other members of the health care team. The benefits of using the nursing process include the following:

- Promotes quality client care

- Decreases omissions and duplications

- Provides a guide for all staff involved to provide consistent and responsive care

- Encourages collaborative management of a client’s health care problems

- Improves client safety

- Improves client satisfaction

- Identifies a client’s goals and strategies to attain them

- Increases the likelihood of achieving positive client outcomes

- Saves time, energy, and frustration by creating a care plan that is accessible to all staff caring for a client

By using these components of the nursing process as a critical thinking model, nurses plan outcomes and interventions that are customized to the client’s specific needs, ensure the interventions are evidence-based, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in meeting the client’s needs.

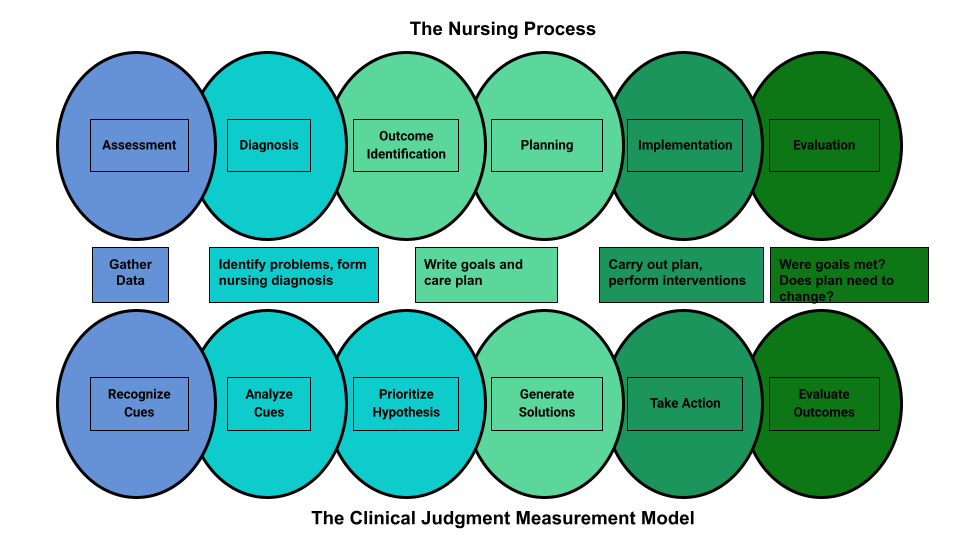

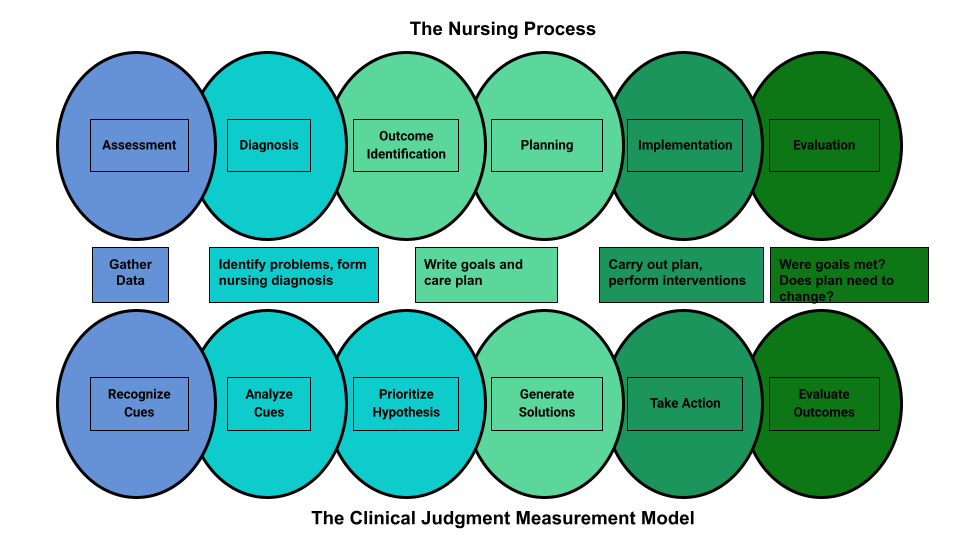

NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model

The NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM) complements the nursing process, but it is a model that assesses an NCLEX candidate’s clinical judgment. Terminology used by this model includes recognize cues, analyze cues, prioritize hypotheses, generate solutions, take action, and evaluate outcomes. See Figure 4.3b[22] and Table 4.2a for comparisons of NCJMM terms and the nursing process.[23],[24],[25]

Figure 4.3b Comparison of the Steps of the NCJMM to the Nursing Process

Table 4.2a Comparison of the NCJMM to the Nursing Process

| NCSBN Clinical Judgment Skill | Description | Corresponding Step of the Nursing Process |

|---|---|---|

| Recognize Cues | What data is clinically significant?

Determining what client findings are significant, most important, and of immediate concern to the nurse (i.e., identifying “relevant cues”). |

Assessment |

| Analyze Cues | What does the data mean?

Analyzing data to determine if it is “expected” or “unexpected” or “normal” or “abnormal” for this client at this time according to their age, development, and clinical status. Making a clinical judgment concerning the client's “human response to health conditions/life processes, or a vulnerability for that response”; also referred to as “forming a hypothesis.” |

Diagnosis

(Analysis of Data) |

| Prioritize Hypotheses | What hypotheses should receive priority attention?

Ranking client conditions and problems according to urgency, complexity, and time. |

Planning |

| Generate Solutions | What should be done?

Planning individualized interventions that meet the desired outcomes for the client; may include gathering additional assessment data. |

Planning |

| Take Action | What will I do now?

Implementing interventions that are safe and most appropriate for the client’s current priority conditions and problems. |

Implementation |

| Evaluate Outcomes | Did the interventions work?

Comparing actual client outcomes with desired client outcomes to determine effectiveness of care and making appropriate revisions to the nursing care plan. |

Evaluation |

Learning activities are incorporated throughout this book to help students practice answering NCLEX Next Generation-style test questions.

Review Scenario A in the following box for an example of a nurse using the nursing process and NCJMM skills while providing client care.

Client Scenario A: Using the Nursing Process[26]

A nurse is caring for a hospitalized client with a medical diagnosis of heart failure who has a prescription to receive furosemide 80mg IV every morning. The nurse uses critical thinking according to the nursing process and the NCJMM before administering the prescribed medication:

Assessment/Recognize Cues: During the morning assessment, the nurse notes that the client has a blood pressure of 98/60, heart rate of 100, respirations of 18, and a temperature of 98.7F.

Diagnosis/Analyze Cues: The nurse reviews the medical record for the client’s vital signs baseline and observes the blood pressure trend is around 110/70 and the heart rate in the 80s.

Planning/Prioritize Hypothesis: The nurse recognizes cues (assessment data) that form a pattern related to fluid imbalance and hypothesizes that the client may be dehydrated.

Planning/Generate Solutions: The nurse gathers additional information and notes the client’s weight has decreased four pounds since yesterday. The nurse talks with the client and validates the hypothesis when the client reports that their mouth feels like cotton, and they feel light-headed. By using critical thinking and clinical judgment, the nurse diagnoses the client with the nursing diagnosis Fluid Volume Deficit and plans interventions for reestablishing fluid balance.

Implementation/Take Action: The nurse withholds the administration of IV furosemide and contacts the health care provider to discuss the client’s current fluid status. After contacting the provider, the nurse initiates additional nursing interventions to promote oral intake and closely monitors hydration status.

Evaluation/Evaluate Outcomes: By the end of the shift, the nurse evaluates the client status and determines that fluid balance has been restored.

In Scenario A, the nurse is using clinical judgment and not just “following orders” to administer the Lasix as scheduled. The nurse assesses the client, recognizes and analyzes cues, creates a hypothesis regarding the fluid status, plans and implements nursing interventions, and evaluates outcomes. While performing these steps, the nurse promotes client safety by contacting the provider before administering a medication that could cause harm to the client at this time.

Holistic Nursing Care

Using the nursing process and clinical judgment while implementing evidence-based practices is referred to as the "science of nursing." Before getting deeper into the science of nursing in the remainder of this chapter, it is important to discuss the "art of nursing" that relies on holistic care provided in a compassionate and caring manner using the nursing process.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines nursing as, “Nursing integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in the recognition of the connection of all humanity.”[27]

The ANA further describes nursing as a learned profession built on a core body of knowledge that integrates both the art and science of nursing. The art of nursing is defined as, "Unconditionally accepting the humanity of others, respecting their need for dignity and worth, while providing compassionate, comforting care."[28]

Nurses care for individuals holistically, including their emotional, spiritual, psychosocial, cultural, and physical needs. They consider problems, issues, and needs that the person experiences as a part of a family and a community as they use the nursing process. Review a scenario illustrating holistic nursing care provided to a client and their family in the following box.

Holistic Nursing Care Scenario

A single mother brings her child to the emergency room for ear pain and a fever. The physician diagnoses the child with an ear infection and prescribes an antibiotic. The mother is advised to make a follow-up appointment with their primary provider in two weeks. While providing discharge teaching, the nurse discovers that the family is unable to afford the expensive antibiotic prescribed and cannot find a primary care provider in their community they can reach by a bus route. The nurse asks a social worker to speak with the mother about affordable health insurance options and available providers in her community and follows up with the prescribing physician to obtain a prescription for a less expensive generic antibiotic. In this manner, the nurse provides holistic care and advocates for improved health for the child and their family.

Caring and the Nursing Process

The American Nurses Association (ANA) states, "The act of caring is foundational to the practice of nursing."[29] Successful use of the nursing process requires the development of a care relationship with the client. A care relationship is a mutual relationship that requires the development of trust between both parties. This trust is often referred to as the development of rapport and underlies the art of nursing. While establishing a caring relationship, the whole person is assessed, including the individual’s beliefs, values, and attitudes, while also acknowledging the vulnerability and dignity of the client and family. Assessing and caring for the whole person takes into account the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of being a human being.[30] Caring interventions can be demonstrated in simple gestures such as active listening, making eye contact, using therapeutic touch, and providing emotional support while respecting their cultural beliefs associated with caring behaviors.[31] See Figure 4.4[32] for an image of a nurse using touch as a therapeutic communication technique to communicate caring.

Dr. Jean Watson is a nurse theorist who has published many works on the art and science of caring in the nursing profession. Her theory of human caring sought to balance the cure orientation of medicine, giving nursing its unique disciplinary, scientific, and professional standing with itself and the public. Dr. Watson’s caring philosophy encourages nurses to be authentically present with their clients while creating a healing environment.[33]

Now that we have discussed basic concepts related to the nursing process, as well as the science and art of nursing, let’s look more deeply at each component of the nursing process in the following sections.

Before learning how to use the nursing process, it is important to understand basic concepts concerning how critical thinking relates to nursing practice. Let's take a deeper look at how nurses think.

Critical Thinking and Clinical Reasoning

Nurses make decisions while providing client care by using critical thinking and clinical reasoning. Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.”[34] Using critical thinking means that nurses take extra steps to maintain client safety and don’t just “follow orders.” It also means the accuracy of client information is validated and plans for caring for clients are based on their needs, current clinical practice, and research.

“Critical thinkers” possess certain attitudes that foster rational thinking. These attitudes are as follows:

- Independence of thought: Thinking on your own

- Fair-mindedness: Treating every viewpoint in an unbiased, unprejudiced way

- Insight into egocentricity and sociocentricity: Thinking of the greater good and not just thinking of yourself. Knowing when you are thinking of yourself (egocentricity) and when you are thinking or acting for the greater good (sociocentricity)

- Intellectual humility: Recognizing your intellectual limitations and abilities

- Nonjudgmental: Using professional ethical standards and not basing your judgments on your own personal or moral standards

- Integrity: Being honest and demonstrating strong moral principles

- Perseverance: Persisting in doing something despite it being difficult

- Confidence: Believing in yourself to complete a task or activity

- Interest in exploring thoughts and feelings: Wanting to explore different ways of knowing

- Curiosity: Asking “why” and wanting to know more

Clinical reasoning is defined as, “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze client information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.”[35] To make sound judgments about client care, nurses must generate alternatives, weigh them against the evidence, and choose the best course of action. The ability to clinically reason develops over time and is based on knowledge and experience.[36]

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning and Clinical Judgment

Inductive and deductive reasoning are important critical thinking skills. They help the nurse use clinical judgment when implementing the nursing process.

Inductive reasoning involves noticing cues, making generalizations, and creating hypotheses based on specific information or incidents. Cues are data that fall outside of expected findings that give the nurse a hint or indication of a client’s potential problem or condition. The nurse organizes these cues into patterns and creates a generalization. A generalization is a judgment formed from a set of facts, cues, and observations and is similar to gathering pieces of a jigsaw puzzle into patterns until the whole picture becomes more clear. Based on generalizations created from patterns of data, the nurse creates a hypothesis regarding a client problem. A hypothesis is a proposed explanation for a situation. It attempts to explain the “why” behind the problem that is occurring. If a “why” is identified, then a solution can begin to be explored.

No one can draw conclusions without first noticing cues. Paying close attention to a client, the environment, and interactions with family members is critical for inductive reasoning. As you work to improve your inductive reasoning, begin by first noticing details about the things around you. A nurse is similar to the detective looking for cues in Figure 4.1.[37] Be mindful of your five primary senses: the things that you hear, feel, smell, taste, and see. Nurses need strong inductive reasoning patterns and be able to take action quickly, especially in emergency situations. They can see how certain objects or events form a pattern (i.e., generalization) that indicates a common problem (i.e., hypothesis).

Example: A nurse assesses a client and finds the surgical incision site is red, warm, and tender to the touch. The nurse recognizes these cues form a pattern of signs of infection and creates a hypothesis that the incision has become infected. The provider is notified of the client’s change in condition, and a new prescription is received for an antibiotic. This is an example of the use of inductive reasoning in nursing practice.

Deductive reasoning is another type of critical thinking that is referred to as “top-down thinking.” Deductive reasoning relies on using a general standard or rule to create a strategy. Deductive reasoning relies on a general statement or hypothesis - sometimes called a premise or standard - that is held to be true. The premise is used to reach a specific, logical conclusion. Nurses use standards set by their state's Nurse Practice Act, federal regulations, the American Nursing Association, professional organizations, and their employer to make decisions about client care and solve problems.

Example: Based on research findings, hospital leaders determine clients recover more quickly if they receive adequate rest. The hospital creates a policy for quiet zones at night by initiating no overhead paging, promoting low-speaking voices by staff, and reducing lighting in the hallways. (See Figure 4.2).[38] The nurse further implements this policy by organizing care for clients that promotes periods of uninterrupted rest at night. This is an example of deductive thinking because the intervention is applied to all clients regardless if they have difficulty sleeping or not.

Clinical judgment is the result of critical thinking and clinical reasoning using inductive and deductive reasoning. Clinical judgment is defined by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) as, “The observed outcome of critical thinking and decision-making. It uses nursing knowledge to observe and assess presenting situations, identify a prioritized client concern, and generate the best possible evidence-based solutions in order to deliver safe client care.”[39] The NCSBN administers the national licensure exam (NCLEX) that evaluates the decision-making ability of nursing graduates and sets a minimum standard for safe, competent nursing care by entry-level licensed nurses. The NCLEX uses the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM) to measure clinical judgment.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is defined by the American Nurses Association (ANA) as, “A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health care consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and client, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.”[40]

Nursing Process

The nursing process is a critical thinking model based on a systematic approach to client-centered care. Nurses use the nursing process to perform clinical reasoning and make clinical judgments when providing client care. The nursing process is based on the Standards of Professional Nursing Practice established by the American Nurses Association (ANA). These standards are authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses (RNs), regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently.[41] The mnemonic ADOPIE is an easy way to remember the ANA Standards and the nursing process. Each letter refers to the six components of the nursing process: Assessment, Diagnosis, Outcomes Identification, Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation.

The nursing process is a continuous, cyclical process that is constantly adapting to the client’s current health status. See Figure 4.3[42] for an illustration of the nursing process.

The ANA's Standards of Professional Nursing Practice associated with each component of the nursing process are described below.

Assessment

The "Assessment" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse collects pertinent data and information relative to the health care consumer’s health or the situation.”[43] A registered nurse uses a systematic method to collect and analyze client data. Assessment includes physiological data, as well as psychological, sociocultural, spiritual, economic, and lifestyle data. For example, a nurse’s assessment of a hospitalized client in pain includes recognizing cues such as the client’s response to pain, such as the inability to get out of bed, refusal to eat, withdrawal from family members, or anger directed at hospital staff.[44]

Licensed practical/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs) assist with gathering data according to their state's scope of practice, but do not analyze data because this is outside their scope of practice. The "Assessment" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Assessment" section of this chapter.

Diagnosis

The "Diagnosis" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse analyzes the assessment data to determine actual or potential diagnoses, problems, and issues.”[45] A nursing diagnosis is the nurse’s clinical judgment about the response from the client to actual or potential health conditions or needs. Nursing diagnoses are the bases for the nurse’s care plan and are different than medical diagnoses.[46]

Analyzing assessment data and formulating a nursing diagnosis is outside the scope of practice for LPN/VNs, and as such, they do not assist with this phase of the nursing process. The "Diagnosis" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Diagnosis" section of this chapter.

Outcome Identification

The "Outcome Identification" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse identifies expected outcomes for a plan individualized to the health care consumer or the situation.”[47] The nurse sets measurable and achievable short- and long-term goals and specific outcomes in collaboration with the client based on their assessment data and nursing diagnoses.

Outcome identification is outside the scope of practice of LPN/VNs, and as such, they do not assist with this phase of the nursing process. The "Outcome Identification" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Outcome Identification" section of this chapter.

Planning

The "Planning" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse develops a collaborative plan encompassing strategies to achieve expected outcomes.”[48] Assessment data, diagnoses, and goals are used to select evidence-based nursing interventions customized to each client’s needs in order to achieve their previously established goals and outcomes. Nursing interventions are planned and documented by RNs in the client's nursing care plan so that nurses, as well as other health professionals, can refer to it for continuity of care.[49]

The "Planning" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Planning" section of this chapter.

Nursing Care Plans

Creating nursing care plans is a part of the "Planning" step of the nursing process. A nursing care plan is a type of documentation that demonstrates the individualized planning and delivery of nursing care for each specific client using the nursing process. RNs create nursing care plans so that the care provided to the client across shifts is consistent among health care personnel. Some interventions can be delegated to LPN/VNs or trained Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAPs) with RN supervision.

Creating the nursing care plan is outside the scope of practice, and as such, the LPN/VNs do not perform this task, although they may contribute to it. Developing nursing care plans and implementing appropriate delegation are further discussed under the “Planning” and “Implementation of Interventions” sections of this chapter.

Implementation

The "Implementation" Standard of Practice is defined as, "The nurse implements the identified plan.”[50] Nursing interventions are implemented or delegated with supervision according to the care plan to assure continuity of care across multiple nurses and health professionals caring for the client. Interventions are documented in the client’s electronic medical record as they are completed.[51] LPN/VNs implement interventions contained in the nursing care plan, provided they are within their scope of practice. The LPN/VN is responsible for documenting the interventions they perform in the client's medical record.

The "Implementation" Standard of Professional Practice also includes the subcategories "Coordination of Care" and "Health Teaching and Health Promotion" to promote health and a safe environment.[52]

The "Implementation" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Implementation of Interventions" section of this chapter.

Evaluation

The "Evaluation" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse evaluates progress toward attainment of goals and outcomes.”[53] During evaluation, nurses reassess the client and compare the findings against established outcomes to determine the effectiveness of the interventions and overall nursing care plan. During this phase, RNs ask, "Were outcomes met? Are any modifications required for the nursing care plan?" Both the client’s status and the effectiveness of the nursing care plan are continuously evaluated and modified as needed.[54]

Evaluating and modifying the nursing care plan is outside the scope of practice of LPN/VNs, although they can assist in gathering assessment data to assist the RN in performing this step of the nursing process. The "Evaluation" component of the nursing process is further described in the "Evaluation" section of this chapter.

Benefits of Using the Nursing Process

Using the nursing process has many benefits for nurses, clients, and other members of the health care team. The benefits of using the nursing process include the following:

- Promotes quality client care

- Decreases omissions and duplications

- Provides a guide for all staff involved to provide consistent and responsive care

- Encourages collaborative management of a client’s health care problems

- Improves client safety

- Improves client satisfaction

- Identifies a client’s goals and strategies to attain them

- Increases the likelihood of achieving positive client outcomes

- Saves time, energy, and frustration by creating a care plan that is accessible to all staff caring for a client

By using these components of the nursing process as a critical thinking model, nurses plan outcomes and interventions that are customized to the client’s specific needs, ensure the interventions are evidence-based, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in meeting the client’s needs.

NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model

The NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM) complements the nursing process, but it is a model that assesses an NCLEX candidate’s clinical judgment. Terminology used by this model includes recognize cues, analyze cues, prioritize hypotheses, generate solutions, take action, and evaluate outcomes. See Figure 4.3b[55] and Table 4.2a for comparisons of NCJMM terms and the nursing process.[56],[57],[58]

Figure 4.3b Comparison of the Steps of the NCJMM to the Nursing Process

Table 4.2a Comparison of the NCJMM to the Nursing Process

| NCSBN Clinical Judgment Skill | Description | Corresponding Step of the Nursing Process |

|---|---|---|

| Recognize Cues | What data is clinically significant?

Determining what client findings are significant, most important, and of immediate concern to the nurse (i.e., identifying “relevant cues”). |

Assessment |

| Analyze Cues | What does the data mean?

Analyzing data to determine if it is “expected” or “unexpected” or “normal” or “abnormal” for this client at this time according to their age, development, and clinical status. Making a clinical judgment concerning the client's “human response to health conditions/life processes, or a vulnerability for that response”; also referred to as “forming a hypothesis.” |

Diagnosis

(Analysis of Data) |

| Prioritize Hypotheses | What hypotheses should receive priority attention?

Ranking client conditions and problems according to urgency, complexity, and time. |

Planning |

| Generate Solutions | What should be done?

Planning individualized interventions that meet the desired outcomes for the client; may include gathering additional assessment data. |

Planning |

| Take Action | What will I do now?

Implementing interventions that are safe and most appropriate for the client’s current priority conditions and problems. |

Implementation |

| Evaluate Outcomes | Did the interventions work?

Comparing actual client outcomes with desired client outcomes to determine effectiveness of care and making appropriate revisions to the nursing care plan. |

Evaluation |

Learning activities are incorporated throughout this book to help students practice answering NCLEX Next Generation-style test questions.

Review Scenario A in the following box for an example of a nurse using the nursing process and NCJMM skills while providing client care.

Client Scenario A: Using the Nursing Process[59]

A nurse is caring for a hospitalized client with a medical diagnosis of heart failure who has a prescription to receive furosemide 80mg IV every morning. The nurse uses critical thinking according to the nursing process and the NCJMM before administering the prescribed medication:

Assessment/Recognize Cues: During the morning assessment, the nurse notes that the client has a blood pressure of 98/60, heart rate of 100, respirations of 18, and a temperature of 98.7F.

Diagnosis/Analyze Cues: The nurse reviews the medical record for the client’s vital signs baseline and observes the blood pressure trend is around 110/70 and the heart rate in the 80s.

Planning/Prioritize Hypothesis: The nurse recognizes cues (assessment data) that form a pattern related to fluid imbalance and hypothesizes that the client may be dehydrated.

Planning/Generate Solutions: The nurse gathers additional information and notes the client’s weight has decreased four pounds since yesterday. The nurse talks with the client and validates the hypothesis when the client reports that their mouth feels like cotton, and they feel light-headed. By using critical thinking and clinical judgment, the nurse diagnoses the client with the nursing diagnosis Fluid Volume Deficit and plans interventions for reestablishing fluid balance.

Implementation/Take Action: The nurse withholds the administration of IV furosemide and contacts the health care provider to discuss the client’s current fluid status. After contacting the provider, the nurse initiates additional nursing interventions to promote oral intake and closely monitors hydration status.

Evaluation/Evaluate Outcomes: By the end of the shift, the nurse evaluates the client status and determines that fluid balance has been restored.

In Scenario A, the nurse is using clinical judgment and not just “following orders” to administer the Lasix as scheduled. The nurse assesses the client, recognizes and analyzes cues, creates a hypothesis regarding the fluid status, plans and implements nursing interventions, and evaluates outcomes. While performing these steps, the nurse promotes client safety by contacting the provider before administering a medication that could cause harm to the client at this time.

Holistic Nursing Care

Using the nursing process and clinical judgment while implementing evidence-based practices is referred to as the "science of nursing." Before getting deeper into the science of nursing in the remainder of this chapter, it is important to discuss the "art of nursing" that relies on holistic care provided in a compassionate and caring manner using the nursing process.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines nursing as, “Nursing integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in the recognition of the connection of all humanity.”[60]

The ANA further describes nursing as a learned profession built on a core body of knowledge that integrates both the art and science of nursing. The art of nursing is defined as, "Unconditionally accepting the humanity of others, respecting their need for dignity and worth, while providing compassionate, comforting care."[61]

Nurses care for individuals holistically, including their emotional, spiritual, psychosocial, cultural, and physical needs. They consider problems, issues, and needs that the person experiences as a part of a family and a community as they use the nursing process. Review a scenario illustrating holistic nursing care provided to a client and their family in the following box.

Holistic Nursing Care Scenario

A single mother brings her child to the emergency room for ear pain and a fever. The physician diagnoses the child with an ear infection and prescribes an antibiotic. The mother is advised to make a follow-up appointment with their primary provider in two weeks. While providing discharge teaching, the nurse discovers that the family is unable to afford the expensive antibiotic prescribed and cannot find a primary care provider in their community they can reach by a bus route. The nurse asks a social worker to speak with the mother about affordable health insurance options and available providers in her community and follows up with the prescribing physician to obtain a prescription for a less expensive generic antibiotic. In this manner, the nurse provides holistic care and advocates for improved health for the child and their family.

Caring and the Nursing Process

The American Nurses Association (ANA) states, "The act of caring is foundational to the practice of nursing."[62] Successful use of the nursing process requires the development of a care relationship with the client. A care relationship is a mutual relationship that requires the development of trust between both parties. This trust is often referred to as the development of rapport and underlies the art of nursing. While establishing a caring relationship, the whole person is assessed, including the individual’s beliefs, values, and attitudes, while also acknowledging the vulnerability and dignity of the client and family. Assessing and caring for the whole person takes into account the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of being a human being.[63] Caring interventions can be demonstrated in simple gestures such as active listening, making eye contact, using therapeutic touch, and providing emotional support while respecting their cultural beliefs associated with caring behaviors.[64] See Figure 4.4[65] for an image of a nurse using touch as a therapeutic communication technique to communicate caring.

Dr. Jean Watson is a nurse theorist who has published many works on the art and science of caring in the nursing profession. Her theory of human caring sought to balance the cure orientation of medicine, giving nursing its unique disciplinary, scientific, and professional standing with itself and the public. Dr. Watson’s caring philosophy encourages nurses to be authentically present with their clients while creating a healing environment.[66]

Now that we have discussed basic concepts related to the nursing process, as well as the science and art of nursing, let’s look more deeply at each component of the nursing process in the following sections.