3. Legal & Ethical Considerations

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN) and Amy Ertwine

Legal Considerations

As discussed earlier in this chapter, nurses can be reprimanded or have their licenses revoked for not appropriately following the Nurse Practice Act in the state they are practicing. Nurses can also be held legally liable for negligence, malpractice, or breach of client confidentiality when providing client care.

Negligence and Malpractice

Negligence is a general term that denotes conduct lacking in due care, carelessness, and a deviation from the standard of care that a reasonable person would use in a particular set of circumstances.[1] Malpractice is a more specific term that looks at a standard of care, as well as the professional status of the caregiver. [2]

To prove negligence or malpractice, the following elements must be established in a court of law[3]:

- Duty owed the client

- Breach of duty owed the client

- Foreseeability

- Causation

- Injury

- Damages

To avoid being sued for negligence or malpractice, it is essential for nurses and nursing students to follow the scope and standards of practice care set forth by their state’s Nurse Practice Act; the American Nurses Association; and employer policies, procedures, and protocols to avoid the risk of losing their nursing license. Examples of a nurse’s breach of duty that can be viewed as negligence includes the following:[4]

- Failure to Assess: Nurses should assess for all potential nursing problems/diagnoses, not just those directly affected by the medical disease. For example, all clients should be assessed for fall risk and appropriate fall precautions implemented.

- Insufficient monitoring: Some conditions require frequent monitoring by the nurse, such as risk for falls, suicide risk, confusion, and self-injury.

- Failure to Communicate:

- Lack of documentation: A basic rule of thumb in a court of law is that if an assessment or action was not documented, it is considered not done. Nurses must document all assessments and interventions, in addition to the specific type of client documentation called a nursing care plan.

- Lack of provider notification: Changes in client condition should be urgently communicated to the health care provider based on client status. Documentation of provider notification should include the date, time, and person notified and follow-up actions taken by the nurse.

- Failure to Follow Protocols: Agencies and states have rules for reporting certain behaviors or concerns. For example, a nurse is considered a mandatory reporter by law and required to report suspicion of abuse or neglect of a child based on data gathered during an assessment.

Patient Self Determination Act

The Patient Self Determination Act (PSDA) of 1990 is an amendment made to the Social Security Act that requires health care facilities to inform clients of their right to be involved in their medical care decisions. This law specifically applies to facilities accepting Medicare or Medicaid funding but is considered a right of all clients regardless of their method of reimbursement.

Under the PSDA, clients must also be asked about their advance directives and care wishes. Clients must be provided with teaching about advance directives, appointment of an agent or surrogate in the event they become incapacitated, and their right to self-determination. Conversations about these topics and clients wishes must be documented in the medical record. It is considered an ethical duty of nurses and other health care professionals to ensure clients are aware and understand these healthcare-associated rights.[5]

Informed Consent

Informed consent is written consent voluntarily signed by a client who is competent and understands the terms of the consent without any form of coercion. In the event the client is a minor or deemed incompetent to make their own decisions, a parent or legal guardian signs the informed consent.[6]

Informed consent is crucial for upholding the client’s right for self-determination. Informed consent provides documentation signed by the client of their understanding of health care being provided; its benefits, risks, potential complications; reasonable alternatives to treatment; and the right to withdraw consent. It is the health care provider’s responsibility to fully discuss the treatment, procedure, or other health care action being proposed that requires consent. The nurse often signs as a witness to the client’s signature on the form, affirming that person signed the form. However, it is not the nurse’s responsibility or role to provide information. If the client (or their parent/legal guardian) expresses questions, concerns, or lack of understanding, the nurse has an ethical responsibility to notify the provider and advocate for further discussion before signing the form.[7]

In emergency situations where the delay to obtain consent would cause undue harm to the client, verbal or telephone consent may be temporarily obtained that is valid for no more than ten days. Verbal consent and the reason for verbal consent must be documented in the medical record by the provider.[8]

See the following box for examples of situations requiring informed consent in the state of Wisconsin according to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

Examples of Situations Requiring Informed Consent[

- Receipt of medications and/or treatment, including psychotropic medications (unless court-ordered)

- Undergoing customary treatment techniques and procedures

- Participation in experimental research

- Undergoing psychosurgery or other psychological treatment procedures

- Release of treatment records

- Videorecording

- Performance of labor beneficial to the facility

Confidentiality

In addition to negligence and malpractice, confidentiality is a major legal consideration for nurses and nursing students. Patient confidentiality is the right of an individual to have personal, identifiable medical information, referred to as their protected health information (PHI), protected and known only by those health care team members directly providing care to them. This right is protected by federal regulations called the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). HIPAA was enacted in 1996 and was prompted by the need to ensure privacy and protection of personal health records and data in an environment of electronic medical records and third-party insurance payers. There are two main sections of HIPAA law, the Privacy Rule and the Security Rule. The Privacy Rule addresses the use and disclosure of individuals’ health information. The Security Rule sets national standards for protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronically protected health information. HIPAA regulations extend beyond medical records and apply to client information shared with others. Therefore, all types of client information should only be shared with health care team members who are actively providing care to them.

How do HIPAA regulations affect you as a student nurse? You are required to adhere to HIPAA guidelines from the moment you begin to provide client care. Nursing students may be disciplined or expelled by their nursing program for violating HIPAA. Nurses who violate HIPAA rules may be fired from their jobs or face lawsuits. See the following box for common types of HIPAA violations and ways to avoid them.

Common HIPAA Violations and Ways to Avoid Them[9]

- Gossiping in the hallways or otherwise talking about clients where other people can hear you. It is understandable that you will be excited about what is happening when you begin working with clients and your desire to discuss interesting things that occur. As a student, you will be able to discuss client care in a confidential manner behind closed doors with your instructor. However, as a health care professional, do not talk about clients in the hallways, elevator, breakroom, or with others who are not directly involved with that client’s care because it is too easy for others to overhear what you are saying.

- Mishandling medical records or leaving medical records unsecured. You can breach HIPAA rules by leaving your computer unlocked for anyone to access or by leaving written client charts in unsecured locations. You should never share your password with anyone else. Make sure that computers are always locked with a password when you step away from them and paper charts are closed and secured in an area where unauthorized people don’t have easy access to them. NEVER take records from a facility or include a client’s name on paperwork that leaves the facility.

- Illegally or unauthorized accessing of client files. If someone you know, like a neighbor, coworker, or family member is admitted to the unit you are working on, do not access their medical record unless you are directly caring for them. Facilities have the capability of tracing everything you access within the electronic medical record and holding you accountable. This rule holds true for employees who previously cared for a client as a student; once your shift is over as a student, you should no longer access that client’s medical records.

- Sharing information with unauthorized people. Anytime you share medical information with anyone but the client themselves, you must have written permission to do so. For instance, if a husband comes to you and wants to know his spouse’s lab results, you must have permission from his spouse before you can share that information with him. Just confirming or denying that a client has been admitted to a unit or agency can be considered a breach of confidentiality. Furthermore, voicemails should not be left regarding protected client information.

- Information can generally be shared with the parents of children until they turn 18, although there are exceptions to this rule if the minor child seeks birth control, an abortion, or becomes pregnant. After a child turns 18, information can no longer be shared with the parent unless written permission is provided, even if the minor is living at home and/or the parents are paying for their insurance or health care. As a general rule, any time you are asked for client information, check first to see if the client has granted permission.

- Texting or e-mailing regarding client information on an unencrypted device. Only use properly encrypted devices that have been approved by your health care facility for e-mailing or faxing protected client information. Also, ensure that the information is being sent to the correct person, address, or phone number.

- Sharing information on social media. Never post anything on social media that has anything to do with your clients, the facility where you are working or have clinical, or even how your day went at the agency. Nurses and other professionals have been fired for violating HIPAA rules on social media.[10],[11],[12]

Social Media Guidelines

Nursing students, nurses, and other health care team members must use extreme caution when posting to Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, and other social media sites. Information related to clients, client care, and/or health care agencies should never be posted on social media; health care team members who violate this guideline can lose their jobs and may face legal action and students can be disciplined or expelled from their nursing program. Be aware that even if you think you are posting in a private group, the information can become public.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) has established the following principles for nurses using social media:[13]

- Nurses must not transmit or place online individually identifiable client information.

- Nurses must observe ethically prescribed professional client-nurse boundaries.

- Nurses should understand that clients, colleagues, organizations, and employers may view postings.

- Nurses should take advantage of privacy settings and seek to separate personal and professional information online.

- Nurses should bring content that could harm a client’s privacy, rights, or welfare to the attention of appropriate authorities.

- Nurses should participate in developing organizational policies governing online conduct.

In addition to these principles, the ANA has also provided these tips for nurses and nursing students using social media:[14]

- Remember that standards of professionalism are the same online as in any other circumstance.

- Do not share or post information or photos gained through the nurse-client relationship.

- Maintain professional boundaries in the use of electronic media. Online contact with clients blurs this boundary.

- Do not make disparaging remarks about clients, employers, or coworkers, even if they are not identified.

- Do not take photos or videos of clients on personal devices, including cell phones.

- Promptly report a breach of confidentiality or privacy.

Read more about the ANA’s Social Media Principles.

Code of Ethics

In addition to legal considerations, there are also several ethical guidelines for nursing care.

There is a difference between morality, ethical principles, and a code of ethics. Morality refers to “personal values, character, or conduct of individuals within communities and societies.”[15] An ethical principle is a general guide, basic truth, or assumption that can be used with clinical judgment to determine a course of action. Four common ethical principles are beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), autonomy (control by the individual), and justice (fairness). A code of ethics is set for a profession and makes their primary obligations, values, and ideals explicit.

The American Nursing Association (ANA) guides nursing practice with the Code of Ethics for Nurses.[16] This code provides a framework for ethical nursing care and a guide for decision-making. The Code of Ethics for Nurses serves the following purposes:

- It is a succinct statement of the ethical values, obligations, duties, and professional ideals of nurses individually and collectively.

- It is the profession’s nonnegotiable ethical standard.

- It is an expression of nursing’s own understanding of its commitment to society.[17]

The ANA Code of Ethics contains nine provisions. See a brief description of each provision in the following box.

Provisions of the ANA Code of Ethics[18]

The nine provisions of the ANA Code of Ethics are briefly described below. The full code is available to read for free at Nursingworld.org.

Provision 1: The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.

Provision 2: The nurse’s primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population.

Provision 3: The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient.

Provision 4: The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice; makes decisions; and takes action consistent with the obligation to promote health and to provide optimal care.

Provision 5: The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth.

Provision 6: The nurse, through individual and collective effort, establishes, maintains, and improves the ethical environment of the work setting and conditions of employment that are conducive to safe, quality health care.

Provision 7: The nurse, in all roles and settings, advances the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and the generation of both nursing and health policy.

Provision 8: The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities.

Provision 9: The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organizations, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy.

The ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights

In addition to publishing the Code of Ethics, the ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights was established to help nurses navigate ethical and value conflicts and life-and-death decisions, many of which are common to everyday practice.

Check your knowledge with the following questions:

- Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services. (n.d.). Negligence and malpractice. https://health.mo.gov/living/lpha/phnursing/negligence.php#:~:text=Negligence%20is%3A,a%20particular%20set%20of%20circumstances. ↵

- Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services. (n.d.). Negligence and malpractice. https://health.mo.gov/living/lpha/phnursing/negligence.php#:~:text=Negligence%20is%3A,a%20particular%20set%20of%20circumstances. ↵

- Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services. (n.d.). Negligence and malpractice. https://health.mo.gov/living/lpha/phnursing/negligence.php#:~:text=Negligence%20is%3A,a%20particular%20set%20of%20circumstances. ↵

- Vera, M. (2020). Nursing care plan (NCP): Ultimate guide and database. https://nurseslabs.com/nursing-care-plans/#:~:text=Collaborative%20interventions%20are%20actions%20that,to%20gain%20their%20professional%20viewpoint. ↵

- Teoli, D., & Ghassemzadeh, S. (2023). Patient Self-Determination Act. [Updated 2023 Aug 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538297/ ↵

- Wisconsin State Legislature. (2024). Chapter DHS 94: Patient Rights and Resolution of Patient Grievances. ↵

- Strini, V., Schiavolin, R., & Prendin, A. (2021). The role of the nurse in informed consent to treatments: An observational-descriptive study in the Padua hospital. Clinics and Practice, 11(3), 472-483. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/clinpract11030063. ↵

- Wisconsin State Legislature. (2024). DHS 94.03 Informed Consent ↵

- Patterson, A. (2018, July 3). Most common HIPAA violations with examples. Inspired eLearning. https://inspiredelearning.com/blog/hipaa-violation-examples/ ↵

- Karimi, H., & Masoudi Alavi, N. (2015). Florence Nightingale: The mother of nursing. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 4(2), e29475. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4557413/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). About ANA. https://www.nursingworld.org/ana/about-ana/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Scope of practice. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/scope-of-practice/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Social media. https://www.nursingworld.org/social/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Social media. https://www.nursingworld.org/social/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

Prioritization of care for multiple patients while also performing daily nursing tasks can feel overwhelming in today’s fast-paced health care system. Because of the rapid and ever-changing conditions of patients and the structure of one’s workday, nurses must use organizational frameworks to prioritize actions and interventions. These frameworks can help ease anxiety, enhance personal organization and confidence, and ensure patient safety.

Acuity

Acuity and intensity are foundational concepts for prioritizing nursing care and interventions. Acuity refers to the level of patient care that is required based on the severity of a patient’s illness or condition. For example, acuity may include characteristics such as unstable vital signs, oxygenation therapy, high-risk IV medications, multiple drainage devices, or uncontrolled pain. A "high-acuity" patient requires several nursing interventions and frequent nursing assessments.

Intensity addresses the time needed to complete nursing care and interventions such as providing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), performing wound care, or administering several medication passes. For example, a "high-intensity" patient generally requires frequent or long periods of psychosocial, educational, or hygiene care from nursing staff members. High-intensity patients may also have increased needs for safety monitoring, familial support, or other needs.[1]

Many health care organizations structure their staffing assignments based on acuity and intensity ratings to help provide equity in staff assignments. Acuity helps to ensure that nursing care is strategically divided among nursing staff. An equitable assignment of patients benefits both the nurse and patient by helping to ensure that patient care needs do not overwhelm individual staff and safe care is provided.

Organizations use a variety of systems when determining patient acuity with rating scales based on nursing care delivery, patient stability, and care needs. See an example of a patient acuity tool published in the American Nurse in Table 2.3.[2] In this example, ratings range from 1 to 4, with a rating of 1 indicating a relatively stable patient requiring minimal individualized nursing care and intervention. A rating of 2 reflects a patient with a moderate risk who may require more frequent intervention or assessment. A rating of 3 is attributed to a complex patient who requires frequent intervention and assessment. This patient might also be a new admission or someone who is confused and requires more direct observation. A rating of 4 reflects a high-risk patient. For example, this individual may be experiencing frequent changes in vital signs, may require complex interventions such as the administration of blood transfusions, or may be experiencing significant uncontrolled pain. An individual with a rating of 4 requires more direct nursing care and intervention than a patient with a rating of 1 or 2.[3]

Table 2.3. Example of a Patient Acuity Tool[4]

| 1: Stable Patient | 2: Moderate-Risk Patient | 3: Complex Patient | 4: High-Risk Patient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment |

|

|

|

|

| Respiratory |

|

|

|

|

| Cardiac |

|

|

|

|

| Medications |

|

|

|

|

| Drainage Devices |

|

|

|

|

| Pain Management |

|

|

|

|

| Admit/Transfer/Discharge |

|

|

|

|

| ADLs and Isolation |

|

|

|

|

| Patient Score | Most = 1 | Two or > = 2 | Any = 3 | Any = 4 |

Read more about using a patient acuity tool on a medical-surgical unit.

Rating scales may vary among institutions, but the principles of the rating system remain the same. Organizations include various patient care elements when constructing their staffing plans for each unit. Read more information about staffing models and acuity in the following box.

Staffing Models and Acuity

Organizations that base staffing on acuity systems attempt to evenly staff patient assignments according to their acuity ratings. This means that when comparing patient assignments across nurses on a unit, similar acuity team scores should be seen with the goal of achieving equitable and safe division of workload across the nursing team. For example, one nurse should not have a total acuity score of 6 for their patient assignments while another nurse has a score of 15. If this situation occurred, the variation in scoring reflects a discrepancy in workload balance and would likely be perceived by nursing peers as unfair. Using acuity-rating staffing models is helpful to reflect the individualized nursing care required by different patients.

Alternatively, nurse staffing models may be determined by staffing ratio. Ratio-based staffing models are more straightforward in nature, where each nurse is assigned care for a set number of patients during their shift. Ratio-based staffing models may be useful for administrators creating budget requests based on the number of staff required for patient care, but can lead to an inequitable division of work across the nursing team when patient acuity is not considered. Increasingly complex patients require more time and interventions than others, so a blend of both ratio and acuity-based staffing is helpful when determining staffing assignments.[5]

As a practicing nurse, you will be oriented to the elements of acuity ratings within your health care organization, but it is also important to understand how you can use these acuity ratings for your own prioritization and task delineation. Let’s consider the Scenario B in the following box to better understand how acuity ratings can be useful for prioritizing nursing care.

Scenario B

You report to work at 6 a.m. for your nursing shift on a busy medical-surgical unit. Prior to receiving the handoff report from your night shift nursing colleagues, you review the unit staffing grid and see that you have been assigned to four patients to start your day. The patients have the following acuity ratings:

Patient A: 45-year-old patient with paraplegia admitted for an infected sacral wound, with an acuity rating of 4.

Patient B: 87-year-old patient with pneumonia with a low-grade fever of 99.7 F and receiving oxygen at 2 L/minute via nasal cannula, with an acuity rating of 2.

Patient C: 63-year-old patient who is postoperative Day 1 from a right total hip replacement and is receiving pain management via a PCA pump, with an acuity rating of 2.

Patient D: 83-year-old patient admitted with a UTI who is finishing an IV antibiotic cycle and will be discharged home today, with an acuity rating of 1.

Based on the acuity rating system, your patient assignment load receives an overall acuity score of 9. Consider how you might use their acuity ratings to help you prioritize your care. Based on what is known about the patients related to their acuity rating, whom might you identify as your care priority? Although this can feel like a challenging question to answer because of the many unknown elements in the situation using acuity numbers alone, Patient A with an acuity rating of 4 would be identified as the care priority requiring assessment early in your shift.

Although acuity can a useful tool for determining care priorities, it is important to recognize the limitations of this tool and consider how other patient needs impact prioritization.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

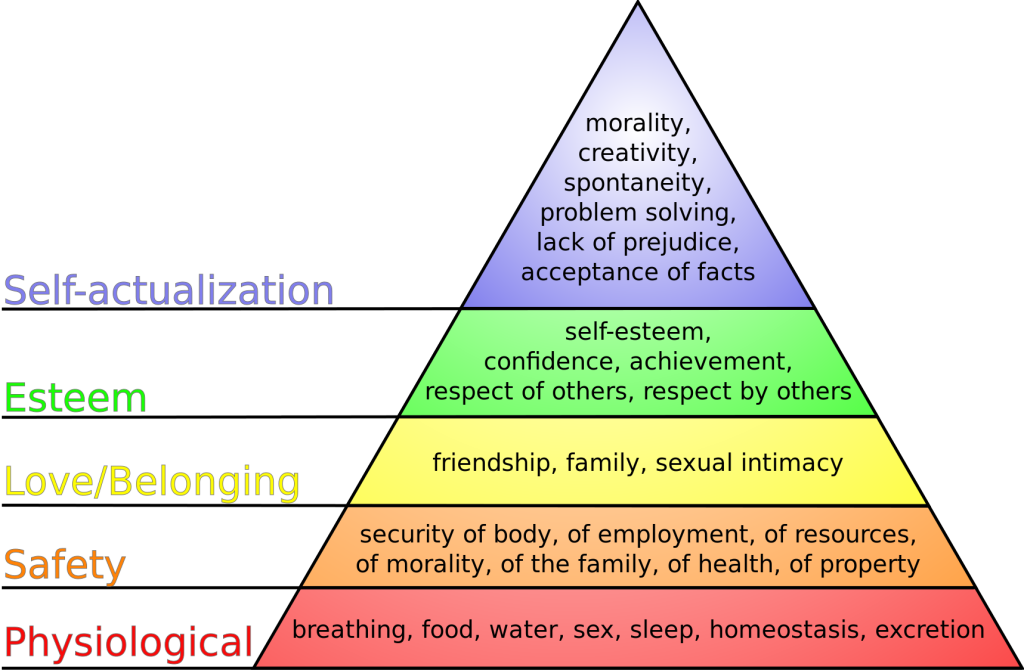

When thinking back to your first nursing or psychology course, you may recall a historical theory of human motivation based on various levels of human needs called Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs reflects foundational human needs with progressive steps moving towards higher levels of achievement. This hierarchy of needs is traditionally represented as a pyramid with the base of the pyramid serving as essential needs that must be addressed before one can progress to another area of need.[6] See Figure 2.1[7] for an illustration of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs places physiological needs as the foundational base of the pyramid.[8] Physiological needs include oxygen, food, water, sex, sleep, homeostasis, and excretion. The second level of Maslow’s hierarchy reflects safety needs. Safety needs include elements that keep individuals safe from harm. Examples of safety needs in health care include fall precautions. The third level of Maslow’s hierarchy reflects emotional needs such as love and a sense of belonging. These needs are often reflected in an individual’s relationships with family members and friends. The top two levels of Maslow’s hierarchy include esteem and self-actualization. An example of addressing these needs in a health care setting is helping an individual build self-confidence in performing blood glucose checks that leads to improved self-management of their diabetes.

So how does Maslow’s theory impact prioritization? To better understand the application of Maslow’s theory to prioritization, consider Scenario C in the following box.

Scenario C

You are an emergency response nurse working at a local shelter in a community that has suffered a devastating hurricane. Many individuals have relocated to the shelter for safety in the aftermath of the hurricane. Much of the community is still without electricity and clean water, and many homes have been destroyed. You approach a young woman who has a laceration on her scalp that is bleeding through her gauze dressing. The woman is weeping as she describes the loss of her home stating, “I have lost everything! I just don’t know what I am going to do now. It has been a day since I have had water or anything to drink. I don’t know where my sister is, and I can’t reach any of my family to find out if they are okay!”

Despite this relatively brief interaction, this woman has shared with you a variety of needs. She has demonstrated a need for food, water, shelter, homeostasis, and family. As the nurse caring for her, it might be challenging to think about where to begin her care. These thoughts could be racing through your mind:

Should I begin to make phone calls to try and find her family? Maybe then she would be able to calm down.

Should I get her on the list for the homeless shelter so she wouldn’t have to worry about where she will sleep tonight?

She hasn’t eaten in a while; I should probably find her something to eat.

All these needs are important and should be addressed at some point, but Maslow’s hierarchy provides guidance on what needs must be addressed first. Use the foundational level of Maslow’s pyramid of physiological needs as the top priority for care. The woman is bleeding heavily from a head wound and has had limited fluid intake. As the nurse caring for this patient, it is important to immediately intervene to stop the bleeding and restore fluid volume. Stabilizing the patient by addressing her physiological needs is required before undertaking additional measures such as contacting her family. Imagine if instead you made phone calls to find the patient’s family and didn't address the bleeding or dehydration - you might return to a severely hypovolemic patient who has deteriorated and may be near death. In this example, prioritizing emotional needs above physiological needs can lead to significant harm to the patient.

Although this is a relatively straightforward example, the principles behind the application of Maslow’s hierarchy are essential. Addressing physiological needs before progressing toward additional need categories concentrates efforts on the most vital elements to enhance patient well-being. Maslow’s hierarchy provides the nurse with a helpful framework for identifying and prioritizing critical patient care needs.

ABCs

Airway, breathing, and circulation, otherwise known by the mnemonic “ABCs,” are another foundational element to assist the nurse in prioritization. Like Maslow’s hierarchy, using the ABCs to guide decision-making concentrates on the most critical needs for preserving human life. If a patient does not have a patent airway, is unable to breathe, or has inadequate circulation, very little of what else we do matters. The patient’s ABCs are reflected in Maslow’s foundational level of physiological needs and direct critical nursing actions and timely interventions. Let’s consider Scenario D in the following box regarding prioritization using the ABCs and the physiological base of Maslow’s hierarchy.

Scenario D

You are a nurse on a busy cardiac floor charting your morning assessments on a computer at the nurses’ station. Down the hall from where you are charting, two of your assigned patients are resting comfortably in Room 504 and Room 506. Suddenly, both call lights ring from the rooms, and you answer them via the intercom at the nurses’ station.

Room 504 has an 87-year-old male who has been admitted with heart failure, weakness, and confusion. He has a bed alarm for safety and has been ringing his call bell for assistance appropriately throughout the shift. He requires assistance to get out of bed to use the bathroom. He received his morning medications, which included a diuretic about 30 minutes previously, and now reports significant urge to void and needs assistance to the bathroom.

Room 506 has a 47-year-old woman who was hospitalized with new onset atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. The patient underwent a cardioversion procedure yesterday that resulted in successful conversion of her heart back into normal sinus rhythm. She is reporting via the intercom that her "heart feels like it is doing that fluttering thing again” and she is having chest pain with breathlessness.

Based upon these two patient scenarios, it might be difficult to determine whom you should see first. Both patients are demonstrating needs in the foundational physiological level of Maslow’s hierarchy and require assistance. To prioritize between these patients' physiological needs, the nurse can apply the principles of the ABCs to determine intervention. The patient in Room 506 reports both breathing and circulation issues, warning indicators that action is needed immediately. Although the patient in Room 504 also has an urgent physiological elimination need, it does not overtake the critical one experienced by the patient in Room 506. The nurse should immediately assess the patient in Room 506 while also calling for assistance from a team member to assist the patient in Room 504.

CURE

Prioritizing what should be done and when it can be done can be a challenging task when several patients all have physiological needs. Recently, there has been professional acknowledgement of the cognitive challenge for novice nurses in differentiating physiological needs. To expand on the principles of prioritizing using the ABCs, the CURE hierarchy has been introduced to help novice nurses better understand how to manage competing patient needs. The CURE hierarchy uses the acronym “CURE” to guide prioritization based on identifying the differences among Critical needs, Urgent needs, Routine needs, and Extras.[9]

“Critical” patient needs require immediate action. Examples of critical needs align with the ABCs and Maslow’s physiological needs, such as symptoms of respiratory distress, chest pain, and airway compromise. No matter the complexity of their shift, nurses can be assured that addressing patients' critical needs is the correct prioritization of their time and energies.

After critical patient care needs have been addressed, nurses can then address “urgent” needs. Urgent needs are characterized as needs that cause patient discomfort or place the patient at a significant safety risk.[10]

The third part of the CURE hierarchy reflects “routine” patient needs. Routine patient needs can also be characterized as "typical daily nursing care" because the majority of a standard nursing shift is spent addressing routine patient needs. Examples of routine daily nursing care include actions such as administering medication and performing physical assessments.[11] Although a nurse’s typical shift in a hospital setting includes these routine patient needs, they do not supersede critical or urgent patient needs.

The final component of the CURE hierarchy is known as “extras.” Extras refer to activities performed in the care setting to facilitate patient comfort but are not essential.[12] Examples of extra activities include providing a massage for comfort or washing a patient’s hair. If a nurse has sufficient time to perform extra activities, they contribute to a patient’s feeling of satisfaction regarding their care, but these activities are not essential to achieve patient outcomes.

Let's apply the CURE mnemonic to patient care in the following box.

If we return to Scenario D regarding patients in Room 504 and 506, we can see the patient in Room 504 is having urgent needs. He is experiencing a physiological need to urgently use the restroom and may also have safety concerns if he does not receive assistance and attempts to get up on his own because of weakness. He is on a bed alarm, which reflects safety considerations related to his potential to get out of bed without assistance. Despite these urgent indicators, the patient in Room 506 is experiencing a critical need and takes priority. Recall that critical needs require immediate nursing action to prevent patient deterioration. The patient in Room 506 with a rapid, fluttering heartbeat and shortness of breath has a critical need because without prompt assessment and intervention, their condition could rapidly decline and become fatal.

Data Cues

In addition to using the identified frameworks and tools to assist with priority setting, nurses must also look at their patients’ data cues to help them identify care priorities. Data cues are pieces of significant clinical information that direct the nurse toward a potential clinical concern or a change in condition. For example, have the patient’s vital signs worsened over the last few hours? Is there a new laboratory result that is concerning? Data cues are used in conjunction with prioritization frameworks to help the nurse holistically understand the patient's current status and where nursing interventions should be directed. Common categories of data clues include acute versus chronic conditions, actual versus potential problems, unexpected versus expected conditions, information obtained from the review of a patient’s chart, and diagnostic information.

Acute Versus Chronic Conditions

A common data cue that nurses use to prioritize care is considering if a condition or symptom is acute or chronic. Acute conditions have a sudden and severe onset. These conditions occur due to a sudden illness or injury, and the body often has a significant response as it attempts to adapt. Chronic conditions have a slow onset and may gradually worsen over time. The difference between an acute versus a chronic condition relates to the body’s adaptation response. Individuals with chronic conditions often experience less symptom exacerbation because their body has had time to adjust to the illness or injury. Let’s consider an example of two patients admitted to the medical-surgical unit complaining of pain in Scenario E in the following box.

Scenario E

As part of your patient assignment on a medical-surgical unit, you are caring for two patients who both ring the call light and report pain at the start of the shift. Patient A was recently admitted with acute appendicitis, and Patient B was admitted for observation due to weakness. Not knowing any additional details about the patients' conditions or current symptoms, which patient would receive priority in your assessment? Based on using the data cue of acute versus chronic conditions, Patient A with a diagnosis of acute appendicitis would receive top priority for assessment over a patient with chronic pain due to osteoarthritis. Patients experiencing acute pain require immediate nursing assessment and intervention because it can indicate a change in condition. Acute pain also elicits physiological effects related to the stress response, such as elevated heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate, and should be addressed quickly.

Actual Versus Potential Problems

Nursing diagnoses and the nursing care plan have significant roles in directing prioritization when interpreting assessment data cues. Actual problems refer to a clinical problem that is actively occurring with the patient. A risk problem indicates the patient may potentially experience a problem but they do not have current signs or symptoms of the problem actively occurring.

Consider an example of prioritizing actual and potential problems in Scenario F in the following box.

Scenario F

A 74-year-old woman with a previous history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is admitted to the hospital for pneumonia. She has generalized weakness, a weak cough, and crackles in the bases of her lungs. She is receiving IV antibiotics, fluids, and oxygen therapy. The patient can sit at the side of the bed and ambulate with the assistance of staff, although she requires significant encouragement to ambulate.

Nursing diagnoses are established for this patient as part of the care planning process. One nursing diagnosis for this patient is Ineffective Airway Clearance. This nursing diagnosis is an actual problem because the patient is currently exhibiting signs of poor airway clearance with an ineffective cough and crackles in the lungs. Nursing interventions related to this diagnosis include coughing and deep breathing, administering nebulizer treatment, and evaluating the effectiveness of oxygen therapy. The patient also has the nursing diagnosis Risk for Skin Breakdown based on her weakness and lack of motivation to ambulate. Nursing interventions related to this diagnosis include repositioning every two hours and assisting with ambulation twice daily.

The established nursing diagnoses provide cues for prioritizing care. For example, if the nurse enters the patient’s room and discovers the patient is experiencing increased shortness of breath, nursing interventions to improve the patient’s respiratory status receive top priority before attempting to get the patient to ambulate.

Although there may be times when risk problems may supersede actual problems, looking to the “actual” nursing problems can provide clues to assist with prioritization.

Unexpected Versus Expected Conditions

In a similar manner to using acute versus chronic conditions as a cue for prioritization, it is also important to consider if a client's signs and symptoms are "expected" or "unexpected" based on their overall condition. Unexpected conditions are findings that are not likely to occur in the normal progression of an illness, disease, or injury. Expected conditions are findings that are likely to occur or are anticipated in the course of an illness, disease, or injury. Unexpected findings often require immediate action by the nurse.

Let’s apply this tool to the two patients previously discussed in Scenario E. As you recall, both Patient A (with acute appendicitis) and Patient B (with weakness and diagnosed with osteoarthritis) are reporting pain. Acute pain typically receives priority over chronic pain. But what if both patients are also reporting nausea and have an elevated temperature? Although these symptoms must be addressed in both patients, they are "expected" symptoms with acute appendicitis (and typically addressed in the treatment plan) but are "unexpected" for the patient with osteoarthritis. Critical thinking alerts you to the unexpected nature of these symptoms in Patient B, so they receive priority for assessment and nursing interventions.

Handoff Report/Chart Review

Additional data cues that are helpful in guiding prioritization come from information obtained during a handoff nursing report and review of the patient chart. These data cues can be used to establish a patient's baseline status and prioritize new clinical concerns based on abnormal assessment findings. Let’s consider Scenario G in the following box based on cues from a handoff report and how it might be used to help prioritize nursing care.

Scenario G

Imagine you are receiving the following handoff report from the night shift nurse for a patient admitted to the medical-surgical unit with pneumonia:

At the beginning of my shift, the patient was on room air with an oxygen saturation of 93%. She had slight crackles in both bases of her posterior lungs. At 0530, the patient rang the call light to go to the bathroom. As I escorted her to the bathroom, she appeared slightly short of breath. Upon returning the patient to bed, I rechecked her vital signs and found her oxygen saturation at 88% on room air and respiratory rate of 20. I listened to her lung sounds and noticed more persistent crackles and coarseness than at bedtime. I placed the patient on 2 L/minute of oxygen via nasal cannula. Within five minutes, her oxygen saturation increased to 92%, and she reported increased ease in respiration.

Based on the handoff report, the night shift nurse provided substantial clinical evidence that the patient may be experiencing a change in condition. Although these changes could be attributed to lack of lung expansion that occurred while the patient was sleeping, there is enough information to indicate to the oncoming nurse that follow-up assessment and interventions should be prioritized for this patient because of potentially worsening respiratory status. In this manner, identifying data cues from a handoff report can assist with prioritization.

Now imagine the night shift nurse had not reported this information during the handoff report. Is there another method for identifying potential changes in patient condition? Many nurses develop a habit of reviewing their patients’ charts at the start of every shift to identify trends and “baselines” in patient condition. For example, a chart review reveals a patient’s heart rate on admission was 105 beats per minute. If the patient continues to have a heart rate in the low 100s, the nurse is not likely to be concerned if today’s vital signs reveal a heart rate in the low 100s. Conversely, if a patient’s heart rate on admission was in the 60s and has remained in the 60s throughout their hospitalization, but it is now in the 100s, this finding is an important cue requiring prioritized assessment and intervention.

Diagnostic Information

Diagnostic results are also important when prioritizing care. In fact, the National Patient Safety Goals from The Joint Commission include prompt reporting of important test results. New abnormal laboratory results are typically flagged in a patient’s chart or are reported directly by phone to the nurse by the laboratory as they become available. Newly reported abnormal results, such as elevated blood levels or changes on a chest X-ray, may indicate a patient’s change in condition and require additional interventions. For example, consider Scenario H in which you are the nurse providing care for five medical-surgical patients.

Scenario H

You completed morning assessments on your assigned five patients. Patient A previously underwent a total right knee replacement and will be discharged home today. You are about to enter Patient A’s room to begin discharge teaching when you receive a phone call from the laboratory department, reporting a critical hemoglobin of 6.9 gm/dL on Patient B. Rather than enter Patient A’s room to perform discharge teaching, you immediately reprioritize your care. You call the primary provider to report Patient B’s critical hemoglobin level and determine if additional intervention, such as a blood transfusion, is required.

Prioritization Principles & Staffing Considerations[13]

With the complexity of different staffing variables in health care settings, it can be challenging to identify a method and solution that will offer a resolution to every challenge. The American Nurses Association has identified five critical principles that should be considered for nurse staffing. These principles are as follows:

- Health Care Consumer: Nurse staffing decisions are influenced by the specific number and needs of the health care consumer. The health care consumer includes not only the client, but also families, groups, and populations served. Staffing guidelines must always consider the patient safety indicators, clinical, and operational outcomes that are specific to a practice setting. What is appropriate for the consumer in one setting, may be quite different in another. Additionally, it is important to ensure that there is resource allocation for care coordination and health education in each setting.

- Interprofessional Teams: As organizations identify what constitutes appropriate staffing in various settings, they must also consider the appropriate credentials and qualifications of the nursing staff within a specific setting. This involves utilizing an interprofessional care team that allows each individual to practice to the full extent of their educational, training, scope of practice as defined by their state Nurse Practice Act, and licensure. Staffing plans must include an appropriate skill mix and acknowledge the impact of more experienced nurses to help serve in mentoring and precepting roles.

- Workplace culture: Staffing considerations must also account for the importance of balance between costs associated with best practice and the optimization of care outcomes. Health care leaders and organizations must strive to ensure a balance between quality, safety, and health care cost. Organizations are responsible for creating work environments, which develop policies allowing for nurses to practice to the full extent of their licensure in accordance with their documented competence. Leaders must foster a culture of trust, collaboration, and respect among all members of the health care team, which will create environments that engage and retain health care staff.

- Practice environment: Staffing structures must be founded in a culture of safety where appropriate staffing is integral to achieve patient safety and quality goals. An optimal practice environment encourages nurses to report unsafe conditions or poor staffing that may impact safe care. Organizations should ensure that nurses have autonomy in reporting and concerns and may do so without threat of retaliation. The ANA has also taken the position to state that mandatory overtime is an unacceptable solution to achieve appropriate staffing. Organizations must ensure that they have clear policies delineating length of shifts, meal breaks, and rest period to help ensure safety in patient care.

- Evaluation: Staffing plans should be consistently evaluated and changed based upon evidence and client outcomes. Environmental factors and issues such as work-related illness, injury, and turnover are important elements of determining the success of need for modification within a staffing plan.[14]

Prioritization of patient care should be grounded in critical thinking rather than just a checklist of items to be done. Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow."[15] Certainly, there are many actions that nurses must complete during their shift, but nursing requires adaptation and flexibility to meet emerging patient needs. It can be challenging for a novice nurse to change their mindset regarding their established “plan” for the day, but the sooner a nurse recognizes prioritization is dictated by their patients’ needs, the less frustration the nurse might experience. Prioritization strategies include collection of information and utilization of clinical reasoning to determine the best course of action. Clinical reasoning is defined as, “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.”[16] Clinical reasoning is fostered within nurses when they are challenged to integrate data in various contexts. The clinical reasoning cycle begins when nurses first consider a client situation and progress to collecting cues and information. As nurses process the information, they begin to identify problems and establish realistic goals. They then take appropriate actions and evaluate outcomes. Finally, they reflect upon the process and the learning that has occurred. The reflection piece is critical for solidifying or changing future actions and developing knowledge.

When nurses use critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills, they set forth on a purposeful course of intervention to best meet patient-care needs. Rather than focusing on one’s own priorities, nurses utilizing critical thinking and reasoning skills recognize their actions must be responsive to their patients. For example, a nurse using critical thinking skills understands that scheduled morning medications for their patients may be late if one of the patients on their care team suddenly develops chest pain. Many actions may be added or removed from planned activities throughout the shift based on what is occurring holistically on the patient-care team.

Additionally, in today’s complex health care environment, it is important for the novice nurse to recognize the realities of the current health care environment. Patients have become increasingly complex in their health care needs, and organizations are often challenged to meet these care needs with limited staffing resources. It can become easy to slip into the mindset of disenchantment with the nursing profession when first assuming the reality of patient-care assignments as a novice nurse. The workload of a nurse in practice often looks and feels quite different than that experienced as a nursing student. As a nursing student, there may have been time for lengthy conversations with patients and their family members, ample time to chart, and opportunities to offer personal cares, such as a massage or hair wash. Unfortunately, in the time-constrained realities of today's health care environment, novice nurses should recognize that even though these “extra” tasks are not always possible, they can still provide quality, safe patient care using the “CURE” prioritization framework. Rather than feeling frustrated about “extras” that cannot be accomplished in time-constrained environments, it is vital to use prioritization strategies to ensure appropriate actions are taken to complete what must be done. With increased clinical experience, a novice nurse typically becomes more comfortable with prioritizing and reprioritizing care.

Time management is not an unfamiliar concept to nursing students because many students are balancing time demands related to work, family, and school obligations. To determine where time should be allocated, prioritization processes emerge. Although the prioritization frameworks of nursing may be different than those used as a student, the concept of prioritization remains the same. Despite the context, prioritization is essentially using a structure to organize tasks to ensure the most critical tasks are completed first and then identify what to move onto next. To truly maximize time management, in addition to prioritization, individuals should be organized, strive for accuracy, minimize waste, mobilize resources, and delegate when appropriate.

Time management is one of the greatest challenges that nurses face in their busy workday. As novice nurses develop their practice, it is important to identify organizational strategies to ensure priority tasks are completed and time is optimized. Each nurse develops a personal process for organizing information and structuring the timing of their assessments, documentation, medication administration, interventions, and patient education. However, one must always remember that this process and structure must be flexible because in a moment’s time, a patient’s condition can change, requiring a reprioritization of care. An organizational tool is important to guide a nurse’s daily task progression. Organizational tools may be developed individually by the nurse or may be recommended by the organization. Tools can be rudimentary in nature, such as a simple time column format outlining care activities planned throughout the shift, or more complex and integrated within an organization’s electronic medical record. No matter the format, an organizational tool is helpful to provide structure and guide progression toward task achievement.

In addition to using an organizational tool, novice nurses should utilize other time management strategies to optimize their time. For example, assessments can start during bedside handoff report, such as what fluids and medications are running and what will need to be replaced soon. Take a moment after handoff reports to prioritize which patients you will see first during your shift. Other strategies such as grouping tasks, gathering appropriate equipment prior to initiating nursing procedures, and gathering assessment information while performing tasks are helpful in minimizing redundancy and increasing efficiency. For example, observe an experienced nurse providing care and note the efficient processes they use. They may conduct an assessment, bring in morning medications, flush an IV line, collect a morning blood glucose level, and provide patient education about medications all during one patient encounter. Efficiency becomes especially important if the patient has transmission-based precautions and the time spent donning and doffing PPE are considered. The realities of the time-constrained health care environments often necessitate clustering tasks to ensure that all patient-care tasks are completed. Furthermore, nurses who do not manage their time effectively may inadvertently place their patients at risk as a result of delayed care.[17] Effective time management benefits both the patient and the nursing staff.

Time estimation is an additional helpful strategy to facilitate time management. Time estimation involves the review of planned tasks for the day and allocating time estimated to complete the task. Time estimation is especially helpful for novice nurses as they begin to structure and prioritize their shift based on the list of tasks that are required.[18] For example, estimating the time it will take to perform an assessment and administer morning medications to one patient allows the nurse to better plan when to complete the dressing change on another patient. Without using time estimation, the nurse may attempt to group all care tasks with the morning assessments and not leave themselves enough time to administer morning medications within the desired administration time window. Additionally, working in a time-constrained environment without using time estimation strategies increases the likelihood of performing tasks “in a rush” and subsequently increasing the potential for error.

Who’s On My Team?

One of the most critical strategies to enhance time management is to mobilize the resources of the nursing team. The nursing care team includes advanced practice registered nurses (APRN), registered nurses (RN), licensed practical/vocational nurses (LPN/VN), and assistive personnel (AP). AP (formerly referred to as unlicensed assistive personnel [UAP]) include, but are not limited to, certified nursing assistants or aides (CNA), patient-care technicians (PCT), certified medical assistants (CMA), certified medication aides, and home health aides.[19] Each care environment may have a blend of staff, and it is important to understand the legalities associated with the scope and role of each member and what can be safely and appropriately delegated to other members of the team. For example, assistive personnel may be able to assist with ambulating a patient in the hallway, but they would not be able to help administer morning medications. Dividing tasks appropriately among nursing team members can help ensure that the required tasks are completed and individual energies are best allocated to meet patient needs. The nursing care team and requirements around the process of delegation are explored in detail in the "Delegation and Supervision" chapter.

Sam is a novice nurse who is reporting to work for his 0600 shift on the medical telemetry/progressive care floor. He is waiting to receive handoff report from the night shift nurse for his assigned patients. The information that he has received thus far regarding his patient assignment includes the following:

- Room 501: 64-year-old patient admitted last night with heart failure exacerbation. Patient received furosemide 80mg IV push at 2000 with 1600 mL urine output. He is receiving oxygen via nasal cannula at 2L/minute. According to the night shift aide, he has been resting comfortably overnight.

- Room 507: 74-year-old patient admitted yesterday for possible cardioversion due to new onset of atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and is scheduled for transesophageal echocardiogram and possible cardioversion at 1000.

- Room 512: 82-year-old patient who is scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery today at 0700 and is receiving an insulin infusion.

- Room 536: 72-year-old patient who had a negative heart catheterization yesterday but experienced a groin bleed; plans for discharge this morning.

Based on the limited information Sam has thus far, he begins to prioritize his activities for the morning. With what is known thus far regarding his patient assignment, whom might Sam plan to see first and why? What principles of prioritization might be applied?

Although Sam would benefit from hearing a full report on his patients and reviewing the patient charts, he can already begin to engage in strategies for prioritization. Based on the information that has been shared thus far, Sam determines that none of the patients assigned to him are experiencing critical or urgent needs. All the patients' basic physiological needs are being met, but many have actual clinical concerns. Based on the time constraint with scheduled surgery and the insulin infusion for the patient in Room 512, this patient should take priority in Sam's assessments. It is important for Sam to ensure that this patient's pre-op checklist is complete, and he is stable with the infusion prior to transferring him for surgery. Although Sam may later receive information that alters this priority setting, based on the information he has thus far, he has utilized prioritization principles to make an informed decision.

Sam is a novice nurse who is reporting to work for his 0600 shift on the medical telemetry/progressive care floor. He is waiting to receive handoff report from the night shift nurse for his assigned patients. The information that he has received thus far regarding his patient assignment includes the following:

- Room 501: 64-year-old patient admitted last night with heart failure exacerbation. Patient received furosemide 80mg IV push at 2000 with 1600 mL urine output. He is receiving oxygen via nasal cannula at 2L/minute. According to the night shift aide, he has been resting comfortably overnight.

- Room 507: 74-year-old patient admitted yesterday for possible cardioversion due to new onset of atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and is scheduled for transesophageal echocardiogram and possible cardioversion at 1000.

- Room 512: 82-year-old patient who is scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery today at 0700 and is receiving an insulin infusion.

- Room 536: 72-year-old patient who had a negative heart catheterization yesterday but experienced a groin bleed; plans for discharge this morning.

Based on the limited information Sam has thus far, he begins to prioritize his activities for the morning. With what is known thus far regarding his patient assignment, whom might Sam plan to see first and why? What principles of prioritization might be applied?

Although Sam would benefit from hearing a full report on his patients and reviewing the patient charts, he can already begin to engage in strategies for prioritization. Based on the information that has been shared thus far, Sam determines that none of the patients assigned to him are experiencing critical or urgent needs. All the patients' basic physiological needs are being met, but many have actual clinical concerns. Based on the time constraint with scheduled surgery and the insulin infusion for the patient in Room 512, this patient should take priority in Sam's assessments. It is important for Sam to ensure that this patient's pre-op checklist is complete, and he is stable with the infusion prior to transferring him for surgery. Although Sam may later receive information that alters this priority setting, based on the information he has thus far, he has utilized prioritization principles to make an informed decision.