7.7 Adrenal Disorders

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

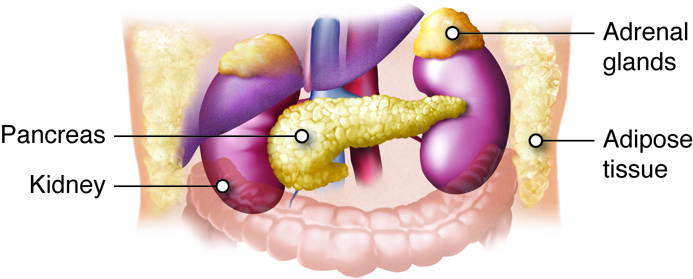

The adrenal glands are a pair of small, triangular-shaped glands located on top of each kidney. See Figure 7.18[1] for an illustration of the location of the adrenal glands.

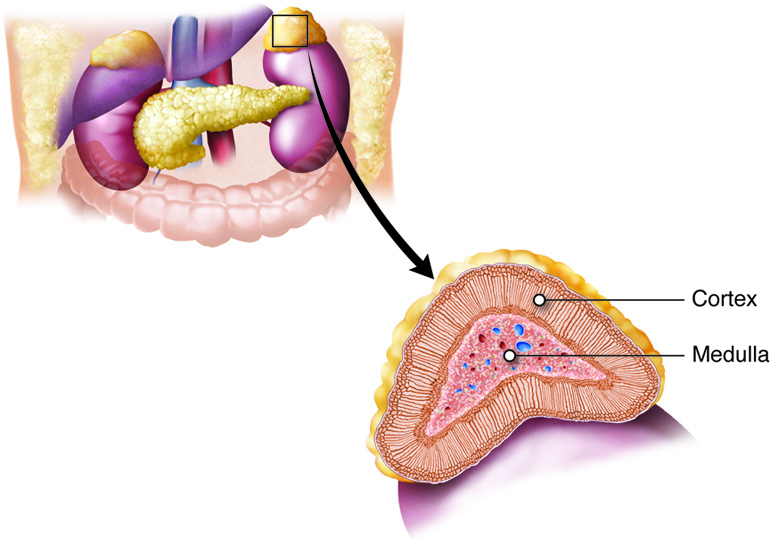

The adrenal glands are responsible for producing several hormones that are essential for maintaining overall health and regulating various body functions. The two primary parts of the adrenal glands are the adrenal cortex and the adrenal medulla, each of which produces different hormones. See Figure 7.19[2] for an illustration of adrenal cortex and adrenal medulla.

The adrenal cortex produces corticosteroids, including cortisol and aldosterone, which help to regulate metabolism, immune response, and salt and water balance. Cortisol is a glucocorticoid hormone produced by the adrenal glands that regulates physiological processes in the body. It is referred to as the “stress hormone” due to its involvement in the body’s stress response. Aldosterone is a mineralocorticoid hormone produced by the adrenal gland that regulates the salt and water balance of the body in the kidneys by increasing the retention of sodium and water and excreting potassium.

The adrenal medulla produces catecholamines, including epinephrine and norepinephrine. These hormones help induce the fight-or-flight response and play a critical role in elevating heart rate and blood pressure to prepare the body in times of stress or danger.[3]

Adrenal Insufficiency: Addison’s Disease

Addison’s disease refers to a specific type of adrenal gland insufficiency, resulting in inadequate production of cortisol and aldosterone. Addison’s disease is often the result of an autoimmune response and destruction of the adrenal glands. It can also occur as the result of tuberculosis; infection; or the sudden cessation of long-term, high-dose glucocorticoid treatment.[4]

Addisonian crisis is a life-threatening medical emergency that occurs when the body’s need for the hormones cortisol and aldosterone exceeds the available supply. This crisis is a severe complication of Addison’s disease, a condition in which the adrenal glands do not produce enough of these critical hormones. The crisis often occurs in response to a stressful event, such as an infection, surgery, trauma, or a significant physical or emotional stressor.[5],[6] Read additional information about Addisonian crisis in the following box.

A Closer Look: Emergency Care of Client in Addisonian Crisis[7]

An Addisonian crisis is a life-threatening situation, and prompt medical attention is crucial. In an Addisonian crisis there is a rapid shift in electrolytes. Sodium (Na) levels fall, leading to hyponatremia, while potassium (K) levels rise, causing hyperkalemia. These electrolyte imbalances can result in various life-threatening complications, including cardiac arrhythmias. Low blood pressure is another hallmark sign of an Addisonian crisis. It occurs due to the loss of aldosterone, which subsequently impairs the body’s ability to retain sodium.

Prompt intervention requires administration of intravenous fluids with saline to rapidly correct the dehydration, raise blood pressure, and correct electrolyte imbalances. These fluids help raise blood pressure and restore blood volume. Intravenous corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone, are administered to rapidly replace the deficient cortisol. If hyperkalemia is present, medications may be given to lower potassium levels and reduce the risk of life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias.

Assessment

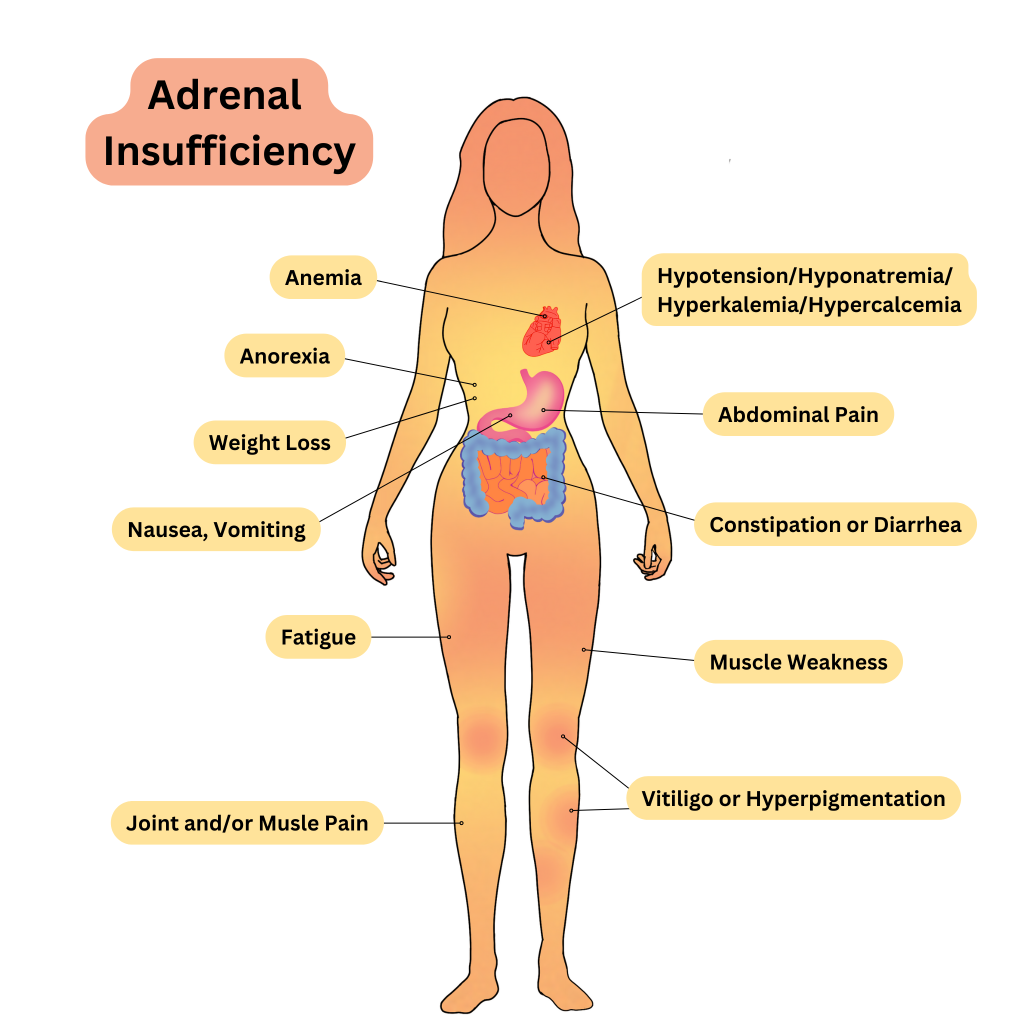

Common assessment findings for adrenal insufficiency can be seen in Table 7.7a.

Table 7.7a. Common Manifestations of Adrenal Insufficiency[8]

| Body System | Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|

| General | Fatigue, weakness, weight loss, and salt cravings |

| Cardiovascular | Hypotension, dizziness, and fainting episodes |

| Gastrointestinal | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, and anorexia (loss of appetite) |

| Musculoskeletal | Muscle weakness, joint pain and stiffness, and muscle and joint aches |

| Endocrine | Hypoglycemia, loss of pubic and axillary hair, amenorrhea (absence of menstrual periods in women), reduced libido and sexual dysfunction, infertility, and oligomenorrhea (infrequent or irregular menstrual periods) |

| Dermatological | Hyperpigmentation (darkening of the skin, especially in sun-exposed areas), skin thinning, easy bruising, vitiligo (loss of skin pigmentation), hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating), and slow wound healing |

| Neurological | Lethargy and apathy, depression and mood changes, difficulty concentrating, confusion and cognitive changes, headache, and irritability |

See Figure 7.20 [9]for an illustration of the clinical manifestations of adrenal insufficiency.

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnosing Addison’s disease involves a combination of clinical assessment, laboratory tests, and specialized tests to confirm adrenal insufficiency. Addison’s disease is characterized by the insufficient production of cortisol and often aldosterone by the adrenal glands, so serum cortisol and aldosterone levels are abnormally low. Additionally, as a result of abnormally low aldosterone levels, electrolyte imbalances can also be found, including hyponatremia (low sodium) and hyperkalemia (elevated potassium).[10] Review normal reference ranges for common diagnostic tests in “Appendix A – Normal Reference Ranges.”

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for clients with adrenal gland hypofunction can help guide nursing care and address the specific needs of these individuals.

Common nursing diagnoses include the following:

- Risk for Imbalanced Fluid Volume

- Impaired Skin Integrity

- Fatigue

- Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and creating expected outcome statements customized for the client’s specific needs. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions.

- The client will maintain adequate fluid balance as evidenced by stable vital signs and absence of signs and symptoms of dehydration or fluid overload.

- The client will exhibit intact skin without any signs of breakdown, ulceration, or infection.

- The client will demonstrate improved ability to perform activities of daily living without excessive fatigue.

- The client will achieve and maintain a stable and appropriate body weight.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical interventions for adrenal insufficiency focus on medication therapy to replace the deficient hormones and effectively manage the condition to prevent adrenal crisis.

Medication Therapy

Clients with Addison’s disease are typically prescribed oral glucocorticoid medications, such as hydrocortisone, prednisone, or dexamethasone, to replace deficient cortisol levels. The dose is often divided into multiple daily doses to mimic the body’s natural cortisol release pattern.

Clients may also require mineralocorticoid replacement with medications like fludrocortisone to replace aldosterone and regulate salt and water balances in the body.

Clients with adrenal insufficiency often have abnormal electrolyte levels. Those presenting with hyperkalemia require urgent treatment to lower their potassium levels, along with close cardiac monitoring.

Review information about treatment of abnormal electrolyte levels in the “Electrolytes” section of the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Hormone Monitoring

Periodic blood tests are conducted to assess hormone levels and adjust medication doses as needed. Clients are educated about the need to increase their glucocorticoid medication during times of illness, injury, or stress to prevent an adrenal crisis.

Lifestyle Changes

Clients are advised to maintain a well-balanced diet and avoid excessive stress, which can exacerbate symptoms.[11]

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for adrenal insufficiency focus on medication management, health teaching, and nutritional support.

Medication Management

Nurses administer prescribed glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement medications during inpatient care according to the health care provider’s orders. Health teaching is provided about proper medication administration techniques and adherence to the medication schedule.

Health Teaching

Nurses provide health teaching about several topics to clients with adrenal insufficiency:

- The disease process and the importance of medication adherence.

- Signs and symptoms of adrenal crises and when to immediately notify the health care provider. Additional doses of medications may be required during illness and stressful situations.

- Wearing a medical alert bracelet or necklace to inform health care professionals of their diagnosis if an emergency should occur.

Nutritional Support

Nurses advocate for multidisciplinary treatment with a registered dietician to develop a well-balanced diet plan and to ensure adequate sodium intake for clients on mineralocorticoid replacement therapy. The nurse also monitors the client’s dietary intake and hydration status.

Evaluation

Evaluation focuses on the effectiveness of the nursing interventions by reviewing the client’s expected outcomes to determine if they were met by the time frames indicated. During the evaluation phase, nurses use critical thinking to analyze reassessment data and determine if a client’s expected outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met by the time frames established. If outcomes are not met or only partially met by the time frame indicated, the care plan should be revised. Reassessment should occur every time the nurse interacts with a client, reviews updated laboratory or diagnostic test results, or discusses the care plan with others on the interprofessional team.

Nurses refer to the previously identified outcome statements and perform reassessments to determine if they have been met by the current nursing care plan or if additional interventions are required. For example, the nurse would perform assessments related to the previously established outcome criteria and determine if they were “met” or if additional interventions are required.

Cushing’s Disease & Cushing’s Syndrome

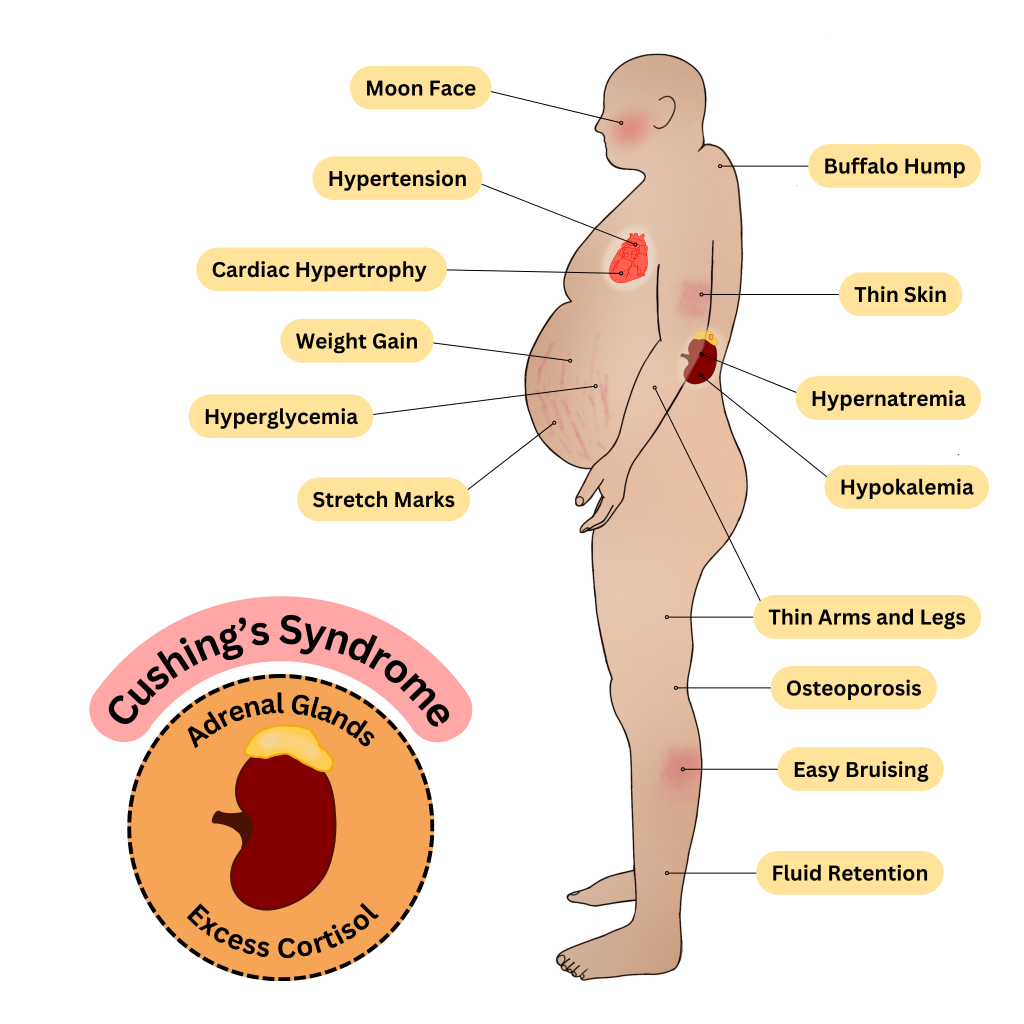

Excessive amounts of adrenal hormones, including glucocorticoids (cortisol), mineralocorticoids (aldosterone), and/or catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine), can be caused by a medical condition or a side effect of other medications. Cushing’s disease is typically caused by a benign tumor in the adrenal gland that causes excess hormone production. Cushing’s syndrome is caused by excess glucocorticoid blood levels caused by medication therapy for another medical problem, such as COPD or immunosuppressive therapy after an organ transplant. In both cases, excessive glucocorticoids can cause widespread issues throughout the body.[12]

Assessment

Common assessment findings for Cushing’s disease and Cushing’s syndrome are summarized in Table 7.7b.

Table 7.7b. Common Manifestations of Cushing’s Disease and Cushing’s Syndrome[13]

| Body System | Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Endocrine | Elevated blood pressure, impaired glucose tolerance, and weight gain and obesity with classic signs such as a collection of fat on the back of the neck between the shoulder blades and a round face |

| Cardiovascular | Hypertension, palpitations, and rapid heart rate |

| Musculoskeletal | Muscle weakness and wasting and increased risk of fracture |

| Integumentary | Easy bruising and thinning of the skin and purple or red stretch marks (striae) |

| Gastrointestinal | Abdominal obesity and central weight gain, increased appetite, and overeating |

| Neurological | Mood changes, including anxiety and depression, irritability, headaches, and cognitive impairment |

| Immune | Increased susceptibility to infections, delayed wound healing, and poor scar formation |

| Reproductive | Irregular menstrual periods in women with PCOS, hirsutism (excessive hair growth) in women, and decreased libido and erectile dysfunction in men |

| Renal | Fluid retention and edema and increased urinary frequency and urgency |

| Ocular | Increased intraocular pressure and risk of glaucoma and visual disturbances, including blurry vision |

See Figure 7.21 [14] by for an illustration of common clinical manifestations of Cushing’s Disease and Cushing’s Syndrome.

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing includes blood tests of cortisol and aldosterone levels. Review information about cortisol testing under diagnostic testing in the “Adrenal Insufficiency” subsection. Electrolytes are commonly monitored because excessive aldosterone levels can cause hypernatremia (elevated sodium) and hypokalemia (decreased potassium).[15]

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for clients with excessive adrenal hormones guide nursing care and address the specific needs of these individuals. Common nursing diagnoses include the following:

- Fluid Volume Excess

- Imbalanced Nutrition: More Than Body Requirements

- Disturbed Body Image

- Impaired Skin Integrity

- Risk for Infection

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and creating expected outcome statements customized for the client’s specific needs. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions.

- The client will maintain optimal fluid balance as evidenced by normal blood pressure, no signs of edema, and balanced input and output within normal limits.

- The client will achieve and maintain a healthy body weight, with weight gain within recommended limits, while demonstrating knowledge of appropriate portion sizes and balanced dietary choices.

- The client will exhibit improved body image and self-esteem, as evidenced by positive self-talk, engagement in activities they enjoy, and verbalization of self-acceptance.

- The client will maintain intact skin and prevent skin breakdown, as evidenced by the absence of skin lesions, regular skin assessments, and adherence to recommended skin care routines.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical interventions include surgery or radiation therapy, medication therapy, and lifestyle modifications.

Surgery/Radiation Therapy

Surgery may be used to remove a tumor or the affected area of the adrenal gland in cases of adrenal adenoma or pituitary adenoma. Radiation therapy may also be utilized following surgery.

Medication Therapy

If a client is experiencing Cushing’s disease as a result of glucocorticoid therapy for another condition, the medication may be stopped or reduced, if possible. Medications, such as aminoglutethimide and ketoconazole, may be prescribed to suppress cortisol production. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as spironolactone may also be prescribed to help control blood pressure and manage electrolytes. Beta-blockers may also be prescribed to help manage blood pressure and heart rate.

Read additional information about spironolactone and beta-blockers in the “Cardiovascular & Renal Systems” chapter of Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Lifestyle Modifications

Dietary modifications may be necessary to address weight gain or changes in appetite. Clients may also be advised to reduce sodium intake in conditions of excess aldosterone. Regular exercise, stress management, and healthy lifestyle choices can help manage symptoms and improve overall well-being.[16]

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for Cushing’s disease and Cushing’s syndrome focus on promoting fluid and electrolyte balance, providing health teaching on diet and exercise, and psychological support.

Promoting Fluid and Electrolyte Balance

Nurses monitor for signs of electrolyte imbalances (e.g., potassium levels) and provide education on dietary changes and medications to address these imbalances. Health teaching about dietary sodium restrictions is provided, if necessary, to help manage fluid balance.

Health Teaching

Nurses provide health teaching to clients with Cushing’s disease on balanced nutrition and weight management. In collaboration with dieticians, meal plans are developed, and clients are taught about portion control and healthy food choices. Clients are encouraged to participate in regular physical activity to improve muscle strength and overall well-being. Exercise routines are planned that are aligned with their energy level and physical capabilities.

Psychological Support

Nurses provide emotional support and encourage open communication to help clients cope with the chronic nature of their condition and any body image changes. Resources are provided for support groups and counseling, as indicated.

Evaluation

Evaluation focuses on the effectiveness of the nursing interventions by reviewing the client’s expected outcomes to determine if they were met by the time frames indicated. During the evaluation phase, nurses use critical thinking to analyze reassessment data and determine if a client’s expected outcomes have been met, partially met, or not met by the time frames established. If outcomes are not met or only partially met by the time frame indicated, the care plan should be revised. Reassessment should occur every time the nurse interacts with a client, reviews updated laboratory or diagnostic test results, or discusses the care plan with others on the interprofessional team.

Nurses refer to the previously identified outcome statements and perform reassessments to determine if they have been met by the current nursing care plan or if additional interventions are required. For example, the nurse would perform assessments related to the previously established outcome criteria and determine if they were “met” or if additional interventions are required.

![]() RN Recap: Cushing’s Disease and Cushing’s Syndrome

RN Recap: Cushing’s Disease and Cushing’s Syndrome

View a brief YouTube video overview of Cushing’s disease and Cushing’s syndrome[17]:

![]() RN Recap: Adrenal Insufficiency

RN Recap: Adrenal Insufficiency

View a brief YouTube video overview of adrenal insufficiency[18]:

View a supplementary YouTube video[19] comparing Addison’s disease and Cushing’s disease:

Media Attributions

- E_M1_13

- E_M1_14a

- Adrenal Insufficiency

- Cushing’s Syndrome

- “E_M1_13.jpg” by SBCCOE is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Access for free at https://pressbooks.ccconline.org/bio106/chapter/endocrine-structures-and-functions/. ↵

- “E_M1_14a.jpg” by SBCCOE is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Access for free at https://pressbooks.ccconline.org/bio106/chapter/endocrine-structures-and-functions/. ↵

- Roman, S., & Wu, L. (2022). Surgical anatomy of the adrenal glands. UpToDate. Retrieved October 26, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Niema, L., & DeSantis, A. (2023). Determining the etiology of adrenal insufficiency in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 26, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Niema, L., & DeSantis, A. (2023). Determining the etiology of adrenal insufficiency in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 26, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Nieman, L., & DeSantis, A. (2023). Treatment of adrenal insufficiency in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 27, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Nieman, L., & DeSantis, A. (2023). Treatment of adrenal insufficiency in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 27, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Nieman, L. K. (2022). Clinical manifestations of adrenal insufficiency in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 27, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- "Adrenal Insufficiency" by Meredith Pomietlo is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- Nieman, L., & DeSantis, A. (2023). Treatment of adrenal insufficiency in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 27, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Nieman, L., & DeSantis, A. (2023). Treatment of adrenal insufficiency in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 27, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Nieman, L. K. (2022). Causes and pathophysiology of Cushing syndrome. UpToDate. Retrieved October 29, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Nieman, L. K. (2023). Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of Cushing syndrome. UpToDate. Retrieved October 29, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- "Cushing's Syndrome by Meredith Pomietlo is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- Nieman, L. K. (2023). Establishing the diagnosis of Cushing syndrome. UpToDate. Retrieved October 28, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Nieman, L. K. (2023). Overview of the treatment of Cushing syndrome. UpToDate. Retrieved October 30, 2023, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, April 24).Health Alterations - Chapter 7 Endocrine - Cushing’s syndrome and Cushing’s disease [Video]. YouTube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6To7kidkg0 ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 7 - Adrenal insufficiency [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/dYw0vwib4QU?si=p_VNu76TDiM9nKU- ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN.(2016, April 15). Cushings and Addisons nursing | Addison's disease vs Cushing's syndrome nursing | Endocrine NCLEX. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Reused with permission. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w_I-8aKaq68 ↵

Nurses access patients' veins to collect blood (i.e., perform phlebotomy) and to administer intravenous (IV) therapy. This section will describe several methods for collecting blood, as well as review the basic concepts of IV therapy.

Blood Collection

Nurses collect blood samples from patients using several methods, including venipuncture, capillary blood sampling, and blood draws from venous access devices. Blood may also be drawn from arteries by specially trained professionals for certain laboratory testing.

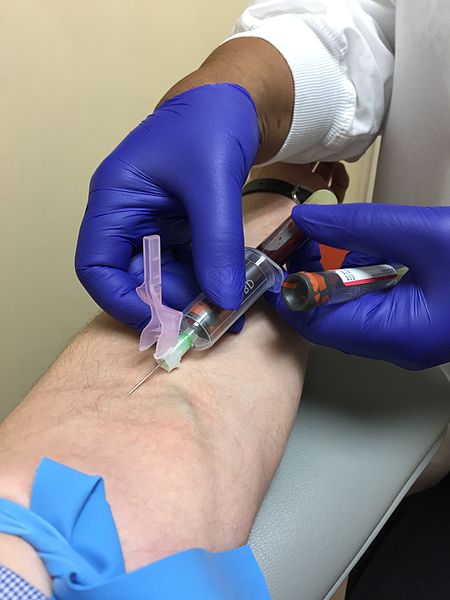

Venipuncture

Venipuncture involves the process of introducing a needle into a patient’s vein to collect a blood sample or insert an IV catheter. See Figure 23.1[1] for an image of venipuncture. Blood sampling with venipuncture may be initiated by nurses, phlebotomists, or other trained personnel. Venipuncture for collection of a blood sample is an important part of data collection to assess a patient’s health status. It is commonly performed to examine hematologic and immune issues such as the body’s oxygen-carrying capacity, infection, and clotting function. It is also useful for assessing metabolic and nutrition issues such as electrolyte status and kidney functioning.

Blood collection is commonly performed via venipuncture from veins in the arms or hands. The most common sites for venipuncture are the large veins located on the antecubital fossa (i.e., the inner side of the elbow). These veins are often preferred for venipuncture because their larger size increases their ability to withstand repetitive blood sampling. However, these veins are not preferred for intravenous therapy due to the mechanical obstruction that can occur in the IV catheter when the elbow joint is contracted.

To perform the skill of venipuncture, the nurse performs many similar steps that occur with IV cannulation. The process of venipuncture for blood sample collection is outlined in the Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills "Perform Venipuncture Blood Draw" checklist.

Blood Samples From Central Venous Access Devices

Blood may also be collected by nurses from a patient's existing central venous access device (CVAD). A CVAD is a type of vascular access that involves the insertion of a catheter into a large vein in the arm, neck, chest, or groin.[2]

CVADs are discussed in more detail in the Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills "Manage Central Lines" chapter that also contains the "Obtain a Blood Sample From a CVAD" checklist.

Capillary Blood Sampling

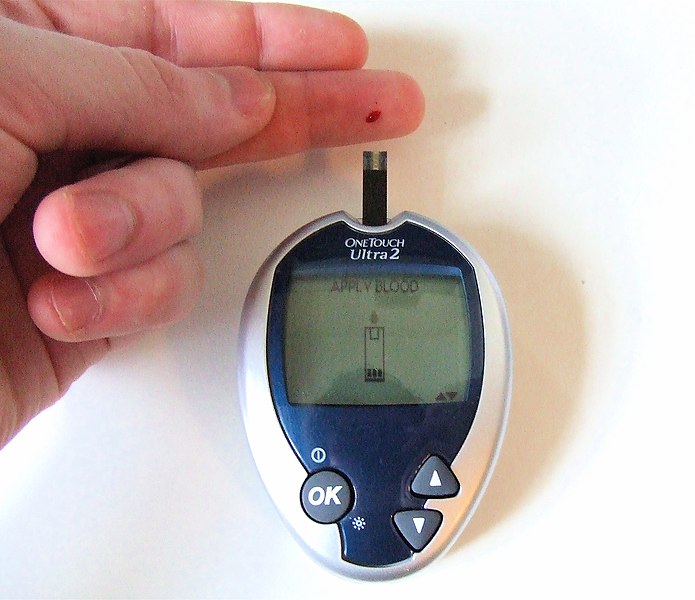

Nurses also collect small amounts of blood for testing via capillary blood sampling. Capillary blood testing occurs when blood is collected from capillaries located near the surface of the skin. Capillaries in the fingers are used for testing in adults whereas capillaries in the heels are used for infants. An example of capillary blood testing is bedside glucose testing. See Figure 23.2[3] for an image of capillary blood glucose testing.

Capillary blood testing is typically used when repetitive sampling is needed. However, not all blood tests can be performed on capillary blood, and some clinical conditions make capillary blood testing inappropriate, such as when a patient is hypotensive with limited venous return.

Review how to perform capillary blood glucose testing in the "Blood Glucose Monitoring" section of the "Specimen Collection" chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills.

Arterial Blood Sampling

Arterial blood sampling occurs when blood is obtained via puncture into an artery by specially trained registered nurses and other health care personnel, such as respiratory therapists, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. Arterial blood collection is most commonly performed to assess the body’s acid-base balance in a diagnostic test called an arterial blood gas. (For more information on arterial blood gas interpretation, please review Open RN Nursing Fundamentals Chapter 15). The most common access site for arterial blood sampling is the radial artery. See Figure 23.3[4] for an image of arterial blood sampling. Arterial blood tests are known to be more painful for the patient than venipuncture and have a higher risk of complications such as bleeding and arterial occlusion with subsequent ischemia to the area distal to the puncture.

Arterial Lines

For patients who require repetitive arterial blood sampling or are hemodynamically unstable, an arterial line may be inserted by specially trained personnel. Arterial lines are specialized tubes that are inserted and maintained in an artery to assist with continuous blood pressure monitoring. They also allow for repeated blood sampling without repetitive puncture, thus decreasing the amount of discomfort for the patient. The radial artery is the most common site used for arterial lines. Nurses must not confuse arterial lines with peripheral or central vein access devices. Arterial lines can be distinguished from venous lines by their specialized pressure tubing, which is firm and non-pliable and is connected to a pressure bag to maintain constant pressurized fluid in the tubing. Medications, fluid boluses, and maintenance IV fluids must never be infused through an arterial line. See Figure 23.3[5] for an image of arterial lines. The condition of the arterial access site, as well as perfusion of the patient's hand, is continually monitored when an arterial line is in place to prevent complications.

Intravenous Therapy

In addition to collecting blood samples, nurses also access patients' veins to administer intravenous therapy.Intravenous therapy (IV therapy) involves the administration of substances such as fluids, electrolytes, blood products, nutrition, or medications directly into a patient's vein. The intravenous route is preferred to administer fluids and medications when rapid onset of the medication or fluid is needed. The direct administration of medication into the bloodstream allows for a more rapid onset of medication actions, restoration of hydration, and correction of nutritional deficits. IV therapy is often used to restore fluids and/or resolve electrolyte imbalances more efficiently than what would be achieved via the oral route.

Fluid Balance

Fluid balance is an important part of optimal cellular functioning, and administration of fluids via the venous system provides an efficient way to quickly correct fluid imbalances. Additionally, many individuals who are physically unwell may not be able to tolerate fluids administered through their gastrointestinal tract, so IV administration is necessary. When administering IV therapy, the nurse needs to understand the nature of the solution being administered and how it will affect the patient's condition.

When patients experience deficient fluid volume, intravenous (IV) fluids are often used to restore fluid to the intravascular compartment or to facilitate the movement of fluid between compartments through the process of osmosis. There are three types of IV fluids: isotonic, hypotonic, and hypertonic.[6]

Review movement of fluid between compartments of the body in the "Basic Fluid and Electrolyte Concepts" section of the "Fluids and Electrolytes" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

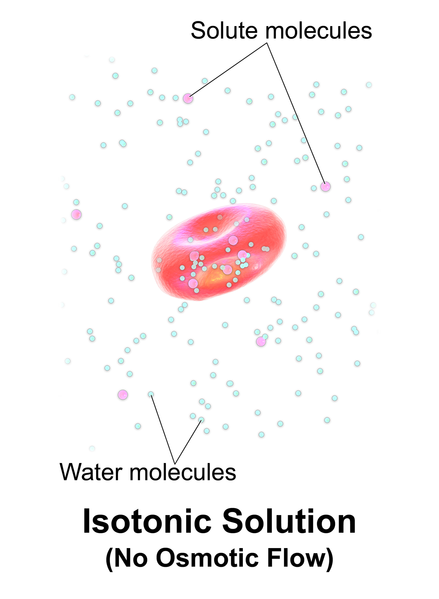

Isotonic Solutions

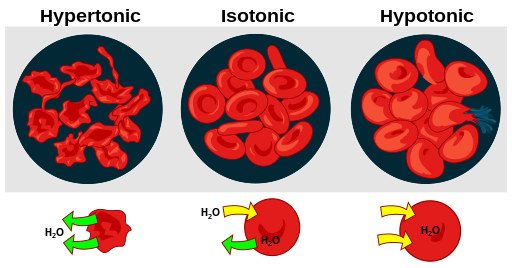

Isotonic solutions are IV fluids that have a similar concentration of dissolved particles as found in the blood. Examples of isotonic IV solutions are 0.9% normal saline (0.9% NaCl) or lactated ringers (LR). Because the concentration of isotonic IV fluid is similar to the concentration of blood, the fluid stays in the intravascular space, and osmosis does not cause fluid movement between cells. See Figure 23.4[7] for an illustration of isotonic IV solution administration that does not cause osmotic movement of fluid.

Isotonic solutions are used to treat fluid volume deficit (also called hypovolemia) to replace extracellular fluid that has been lost due to bleeding, dehydration, shock, burns, trauma, and gastrointestinal tract fluid loss (such as diarrhea). IV therapy with isotonic fluids will increase a patient's blood pressure. However, infusion of too much isotonic fluid can cause excessive fluid volume (also referred to as hypervolemia) and must be used with caution in patients with hypertension, heart failure, and renal disease due to the potential for fluid overload.[8]

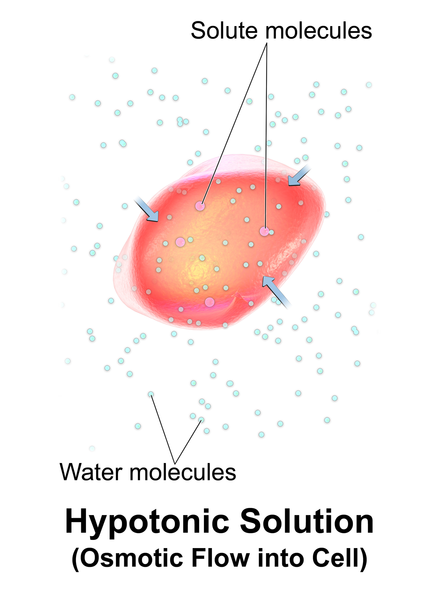

Hypotonic Solutions

Hypotonic solutions have a lower concentration of dissolved solutes than blood. An example of a hypotonic IV solution is 0.45% normal saline (0.45% NaCl). Another example of hypotonic fluid is dextrose 5% in water (D5W). D5W is isotonic in the bag but becomes hypotonic after the dextrose is rapidly metabolized by the body.

When hypotonic IV solutions are infused, it results in a decreased concentration of dissolved solutes in the blood as compared to the intracellular space. This imbalance causes osmotic movement of water from the intravascular compartment into the intracellular space. For this reason, hypotonic fluids are used to treat cellular dehydration. See Figure 23.5[9] for an illustration of the osmotic movement of fluid into a cell when a hypotonic IV solution is administered, causing lower concentration of solutes (pink molecules) in the bloodstream compared to within the cell.[10]

Hypotonic solutions are used for patients whose cells have become dehydrated, such as during diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar hyperglycemia, and fluids must be pushed back into the cells. However, if too much fluid moves out of the intravascular compartment into the cells, cerebral edema, worsening hypovolemia, and hypotension can occur. Therefore, patient status should be monitored carefully when hypotonic solutions are infused.[11]

Hypertonic Solutions

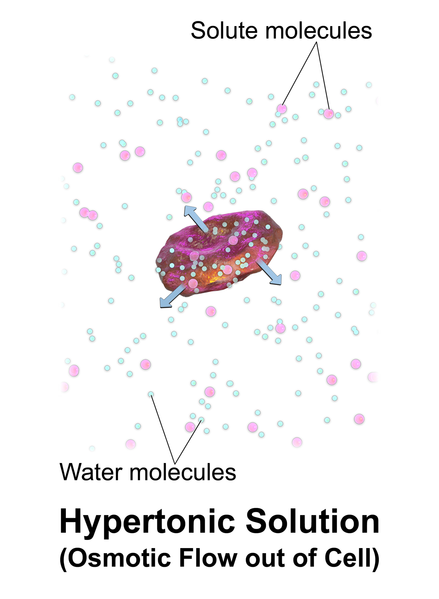

Hypertonic solutions have a higher concentration of dissolved particles than blood. An example of hypertonic IV solution is 3% normal saline (3% NaCl). When infused, hypertonic fluids cause an increased concentration of dissolved solutes in the intravascular space compared to the cells. This causes the osmotic movement of water out of the cells and into the intravascular space to dilute the solutes in the blood. See Figure 23.6[12] for an illustration of osmotic movement of fluid out of a cell when hypertonic IV fluid is administered due to a higher concentration of solutes (pink molecules) in the bloodstream compared to the cell.

Hypertonic solutions move water out of the cells of the body and into the bloodstream. They are commonly used for patients with cerebral edema, severe hyponatremia, or some types of post-op patients. Hypertonic solutions must be used very cautiously due to potentially rapid side effects of fluid overload resulting in pulmonary edema, so they are typically administered in intensive care units (ICU). Hypertonic fluids should not be administered to patients with DKA because it will worsen their cellular dehydration.

When administering hypertonic fluids, it is essential to monitor for signs of fluid overload, such as significantly elevated blood pressure and difficulties breathing. Additionally, if hypertonic solutions with sodium are given, the patient's serum sodium level should be closely monitored.[13]

See Figure 23.7[14] for an illustration comparing how different types of IV solutions affect red blood cell size.

IV fluids are considered medications. As with all medications, nurses must check the rights of medication administration according to agency policy before administering IV fluids. What began as five rights of medication administration has been extended to eight rights according to the American Nurses Association. These eight rights include the following[15]:

- Right Patient

- Right Medication

- Right Dose

- Right Time

- Right Route

- Right Documentation

- Right Reason

- Right Response

Nurses also check for patient allergies, expiration date of the fluid, and compatibility of the fluid with any other fluids, medications, or blood products being administered intravenously. With any IV infusion, it is important for the nurse to pay close attention to the provider's order and make sure that it contains the specific type of fluid, any additives or medications, amount to be infused, rate of infusion, and the length of time that the therapy should continue. The nurse should also carefully assess a patient's hydration status and oral intake to ensure that IV fluids are stopped appropriately as a patent's condition changes. For example, weight should be assessed daily for patients receiving IV fluids to monitor for fluid overload.

Review how to check the rights of medication administration in the “Administration of Enteral Medications” chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills.

Electrolyte Imbalance

In addition to rapidly improving hydration status, IV fluids may also be administered to rapidly correct electrolyte imbalances. Infusing fluids with electrolytes such as potassium, calcium, and magnesium can correct electrolyte imbalances more rapidly and effectively than by oral supplementation. However, nurses must collaborate with the interprofessional team to identify medications that should and should not be given through peripheral veins. Current standards of care consider continuous peripheral infusion therapy of electrolytes to be inappropriate because of potential vascular endothelial damage. Ideally, peripheral IV therapy should be isotonic and consistent with physiological pH; otherwise, central venous access should be used.[16]

Electrolytes administered via the IV route must always be administered cautiously at the correct infusion rate because over supplementation can be deadly. For example, potassium infusions administered too rapidly into a patient's system can cause sudden cardiac arrest.

Blood Administration

Blood and blood components are administered by registered nurses via IV infusion, typically through larger sized IV catheters. Blood and blood components are transfused through a special transfusion administration set that has a filter designed to retain potentially harmful particles. Specific procedures for verifying the correct patient and correct blood product are performed prior to transfusion to prevent transfusion reactions that can be life-threatening. Administration of blood and blood components, including the use of infusion devices and ancillary equipment, and the identification, evaluation, and reporting of adverse events related to transfusion are established in agency policies, procedures, and/or practice guidelines. Read more information about blood administration in the "Administer Blood Products" chapter in Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills.

Nutrition

Nutritional therapy can be administered through an intravenous route for patients who do not have an adequately functioning gastrointestinal tract and/or are unable to take in food or fluids appropriately. Peripheral nutrition may be ordered through a peripheral IV site for nutritional needs such as albumin replacement.

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) may be ordered for a patient based on their specific electrolyte and/or nutritional needs. TPN is a very concentrated solution that must be administered via a central line. Central lines are placed in a larger vessel rather than a smaller, peripheral vessel. Accessing a central vessel requires additional training and expertise to prevent complications with insertion and is further discussed in the Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills "Manage Central Lines” chapter. If a nurse receives an order for TPN therapy for a patient who does not have central line access, the order should be clarified with the prescribing provider.

Medications

The IV route is preferred for the administration of many medications when immediate onset is required. For example, many types of pain medications can be given directly into the bloodstream with a much more rapid onset of action than if they were to be administered orally. Rapid relief of pain can be achieved in minutes rather than hours required for oral medications to reach their peak. Rapid onset can also be achieved with other medications such as those used to treat cardiac emergencies or severe allergic reactions to quickly restore patients to optimal body functioning. Additional information about IV administration of medications is discussed in the Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills "Administer IV Push Medications” chapter.

IV Administration Equipment

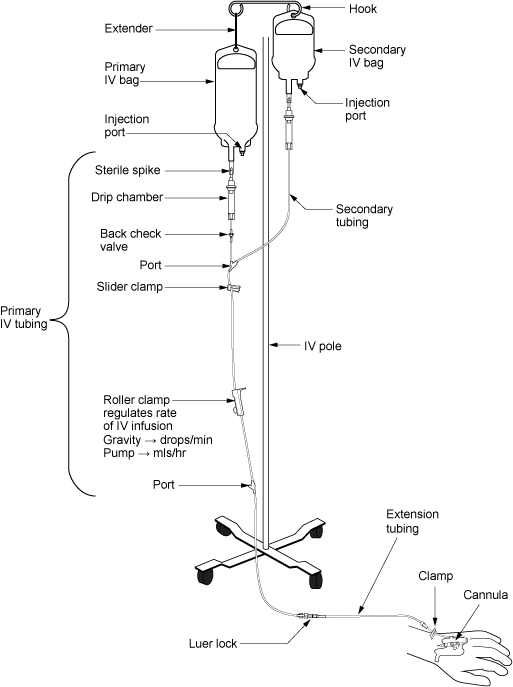

Intravenous (IV) substances are administered through flexible plastic tubing called an IV administration set. The IV administration set connects the bag of solution to the patient’s IV access site. There are two major types of IV administration sets: primary administration sets and secondary administration sets. Administration sets require routine replacement to prevent infection. Follow agency policy regarding tubing changes before initiating a new bag of fluid or medications. See a summary of general guidelines for IV therapy and administration equipment in the box at the end of this section.

Primary Administration Sets

Primary administration sets can be used to infuse continuous or intermittent fluids, electrolytes, or medications. These substances may be administered by infusion pump or by gravity, and each method requires its own type of administration set.

Primary fluids are typically administered using an IV pump. An IV pump is the safest method of administration to ensure specific amounts of fluid are administered. The rate of infusion through an IV pump is typically calculated in mL/hour.

For infusion by gravity, a primary IV administration set can be a macro-drip or a micro-drip solution set. Macro-drip sets are used for routine primary infusions for adults. Micro-drip IV tubing is used in pediatric or neonatal care where small amounts of fluids are administered over a long period of time. A macro-drip infusion set delivers fluid at 10, 15, or 20 drops per milliliter, whereas a micro-drip infusion set delivers 60 drops per milliliter. The drop factor is located on the packaging of the IV tubing and is important to verify when calculating medication administration rates.

Primary IV administration sets consist of the following parts:

- Sterile spike: Used to spike the IV fluid bag and must be kept sterile.

- Roller clamp: Used to regulate the speed or stop an infusion by gravity.

- Drip chamber: Allows air to rise out from a fluid so that it is not passed onto the patient. The drip chamber should be kept ¼ to ½ full of solution. When setting a rate by gravity to "drops per minute," the dripping from this chamber is counted.

- Backcheck valve: Prevents fluid or medication from travelling up into the primary IV bag.

- Access ports: Used to infuse secondary medications and to administer IV push medications. These may also be referred to as “Y ports.”

Secondary Administration Sets

Secondary IV administration sets are used to intermittently administer a secondary medication, such as an antibiotic, while the primary IV is also running. Secondary IV tubing is shorter in length than primary tubing and is connected to a primary line via an access port above the infusion pump. The infusion pump is then set at the prescribed secondary infusion rate while the secondary medication is administered. By hanging the secondary medication bag higher than the primary bag, gravity pulls fluid from the secondary bag until it is empty rather than the primary bag.

Secondary medications may be “piggybacked” into primary infusion lines so the solution from the primary fluid line can be used to prime the secondary tubing. To prime the secondary tubing, after the secondary tubing is connected to the primary tubing, the bag connected to the secondary tubing is held lower than the primary bag, causing fluid from the primary tubing to backflow up the secondary tubing. This eliminates air from the secondary tubing.

See Figure 23.8[17] for an illustration of the setup of primary and secondary administration sets for primary administration of fluids and secondary administration of medication by gravity. See Figure 23.9[18] for an image of an IV infusion pump.

Priming IV Tubing

Primary administration sets, secondary administration sets, and extension tubing must be primed with IV solution to prevent air from entering the patient's circulatory system and causing an air embolism. Priming refers to the process of filling the IV tubing with IV solution prior to attaching it to the patient. Review steps for setting up and priming primary and secondary administration sets using the information in the following box.

Review checklists of steps for "Primary IV Solution Administration" and "Secondary IV Solution Administration" in the "IV Therapy Management" chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills.

Infection Control

Aseptic technique must be maintained throughout all IV therapy procedures, including initiation of IV access, preparing and maintaining IV equipment, administering IV fluids and medications, and discontinuing an IV system. Hand hygiene and strict aseptic technique must be performed when handling all IV equipment. These standards can be reviewed in the “Aseptic Technique” chapter. Additionally, if an IV catheter or IV administration set should become contaminated by contact with a nonsterile surface, it should be replaced with a new one to prevent introducing bacteria or other contaminants into the system.

Types of Venous Access

There are several types of venous access devices used to administer IV therapy that are categorized as peripheral devices or central devices. Venous access device selection is tailored to each patient's needs and to the type, duration, and frequency of infusion.

Peripheral Devices

Peripheral venous access devices are commonly used for short-term IV therapy in the hospital setting. A peripheral IV is an intravenous catheter inserted by percutaneous venipuncture into a peripheral vein and held in place with a sterile transparent dressing. The transparent dressing helps to keep the site sterile, prevents accidental dislodgement, and allows the nurse to visualize the insertion site through the dressing. A securement device may be added to prevent accidental dislodgement.

The patient’s upper extremities (hands and arms) are the preferred sites for insertion. However, a potential limitation of using the hand veins is they are smaller than the cephalic, basilic, or brachial veins in the arm. If the patient requires rapid infusions where a larger gauge IV is warranted, the larger veins in the upper arm should be considered.

Peripheral IVs are used for short-term infusions of fluids, medications, or blood. Peripheral IVs are easy to monitor and can be inserted at the bedside by nurses and other trained professionals. After IV access has been obtained, the hub of an intravenous catheter is attached to a short extension set or a primary IV administration set. Luer lock connectors on the extension tubing and/or administration sets permit syringes to be attached to administer medications or fluid flushes.

Saline lock refers to the use of a short extension set that allows IV access without requiring ongoing IV infusions. When not in use, the lock is flushed with saline according to agency policy and clamped to ensure the site remains sterile and blood does not flow out of the extension tubing. See Figure 23.10[19] for an image of a saline lock.

If the patient requires continuous infusion of IV fluids, the extension tubing from the IV catheter is connected to a primary IV administration set. The IV tubing can be run through an infusion pump to administer fluids or medications at a programmed rate of infusion (typically calculated in mL/hour) or via gravity by setting a drip rate with the roller clamp (typically calculated at drops/minute). Manufacturers list the drop rate on the IV packaging. Because of the risk of error that can occur with infusion by gravity, many agencies require the use of an infusion pump to ensure correct flow rate.

Contraindications to Peripheral IV Access Sites

Before inserting a peripheral IV, the patient should be assessed for contraindications related to insertion sites in the upper extremities. For example, patients who have a history of lumpectomy or mastectomy, an arteriovenous fistula, or current lymphedema often have restrictions that prohibit venipuncture into the affected extremity.[20] Additionally, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), fractures, contractures, or extensive scarring may also prohibit the placement of a peripheral IV. Hospitalized patients may have signage or a bracelet stating "limb alert" to alert heath care professionals to these conditions.

Midline Peripheral Catheters

Midline peripheral catheters have a larger catheter (i.e., 16-18 gauge) that allows for rapid infusions. Insertion is ultrasound-guided and can be inserted by RNs with additional training or other trained professionals. Midline catheters are typically inserted into the basilic, cephalic, or brachial veins of the upper arm with the tip placed near the level of the axilla. They are much longer and inserted deeper than a peripheral IV, but do not extend into a central vessel, so they are not considered a central line. Therefore, they have a lower risk of infection than central venous access. Any medication that can be administered through a peripheral line can be administered via a midline peripheral catheter. They can also be used for longer duration than traditional peripheral venous access, which is ideal for patients needing extended hospital stays or IV access. Based on agency policy, midline catheters may also be used for blood sample collection, thus limiting the number of venipunctures a patient receives. Site care for a midline peripheral catheter is similar to a peripheral IV dressing change.[21],[22]

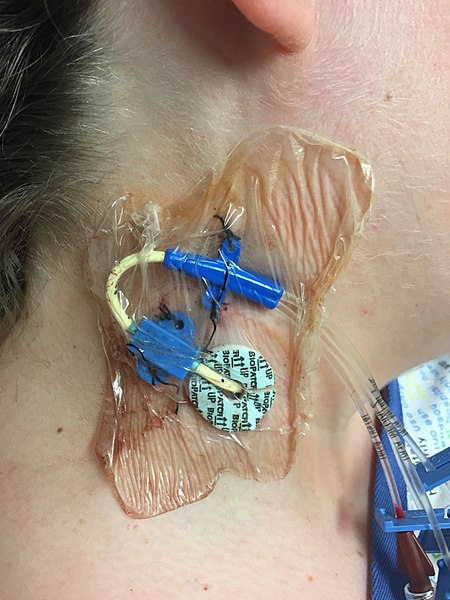

Central Venous Access Devices

A central venous access device (CVAD) is a type of vascular access established by specially trained registered nurses and other health care personnel. It involves the insertion of a tube into a vein in the neck, chest, or groin and threaded into a central vein (most commonly the internal jugular, subclavian, or femoral) and advanced until the tip of the catheter resides within the inferior vena cava, superior vena cava, or right atrium.[23] Only specially trained health professionals may insert central venous access devices, but nurses provide routine care of CVADs, including dressing changes. See Figure 23.11[24] for an image of a central line requiring a dressing change.

A central venous access device can be left in for longer periods of time and is useful for administering concentrated medications and fluids, such as TPN or hyperosmotic fluids, that would be otherwise irritating to smaller peripheral veins. However, central venous access devices have an increased risk for the development of bloodstream infections, so strict sterile technique is required during insertion, and aseptic technique is used for maintenance. Central venous access devices are further discussed in the "Manage Central Lines" chapter of Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills.

Peripheral Inserted Central Catheters

A peripheral inserted central catheter (PICC) is a thin, flexible tube inserted into a vein in the upper arm and guided into the superior vena cava. It is used to give intravenous fluids, blood transfusions, chemotherapy, and other medications requiring a central line. It can also be used for blood sampling. A PICC may stay in place for weeks or months and helps avoid the need for repeated needlesticks. PICC lines are further discussed in the "Manage Central Lines" chapter of Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills.

General Guidelines for IV Therapy

The following are general guidelines for peripheral IV therapy[25]:

- IV fluid therapy is ordered by a provider. The order must include the type of solution or medication, total amount of fluid, rate of infusion, duration, date, and time.

- IV therapy is an invasive procedure. Significant complications can occur if the wrong amount of IV fluids or incorrect medication is given or if aseptic technique is not strictly followed.

- Nurses must understand the indications and duration for IV therapy for each patient. Practice guidelines recommend that patients receiving IV therapy for more than six days should be assessed for an intermediate or long-term device such as a central venous access device (CVAD).

- Hospitalized patients may have an order for a small hourly infusion rate, such as 10-20 mL/hour, historically referred to in practice as a "to keep open" (TKO) or "keep vein open" (KVO) rate.

- IV administration sets require routine replacement to promote patient safety and reduce the risk of infection. Primary and secondary continuous administration sets used to administer solutions other than lipids, blood, or blood products are typically changed every 96 hours, or up to every 7 days, as directed by agency policy and/or the manufacturer’s instructions. Administration sets should also be changed if contamination or compromise in the integrity of the product or system is suspected. Secondary administration sets that are detached from a primary administration set are typically changed every 24 hours or as directed by agency policy. Administration sets should be labelled according to agency policy with the date of initiation or the date of change indicated.[26]

Sunken appearance.

Sunken appearance.

An expansion of the abdomen caused by the accumulation of air or fluid. Patients often report “feeling bloated”.

An expansion of the abdomen caused by the accumulation of air or fluid. Patients often report “feeling bloated”.

Increased peristaltic activity; may be related to diarrhea, obstruction, or digestion of a meal.

Increased peristaltic activity; may be related to diarrhea, obstruction, or digestion of a meal.

Hyperperistalsis, often referred to as “stomach growling”.

Hyperperistalsis, often referred to as “stomach growling”.

Decreased peristaltic activity; may be related to constipation, following abdominal surgery, or with an ileus.

Decreased peristaltic activity; may be related to constipation, following abdominal surgery, or with an ileus.

Voluntary contraction of abdominal wall musculature; may be related to fear, anxiety or presence of cold hands.

Voluntary contraction of abdominal wall musculature; may be related to fear, anxiety or presence of cold hands.

An intense urge to urinate that can lead to urinary incontinence.

An intense urge to urinate that can lead to urinary incontinence.