7.2 Review of Anatomy and Physiology of the Endocrine System

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

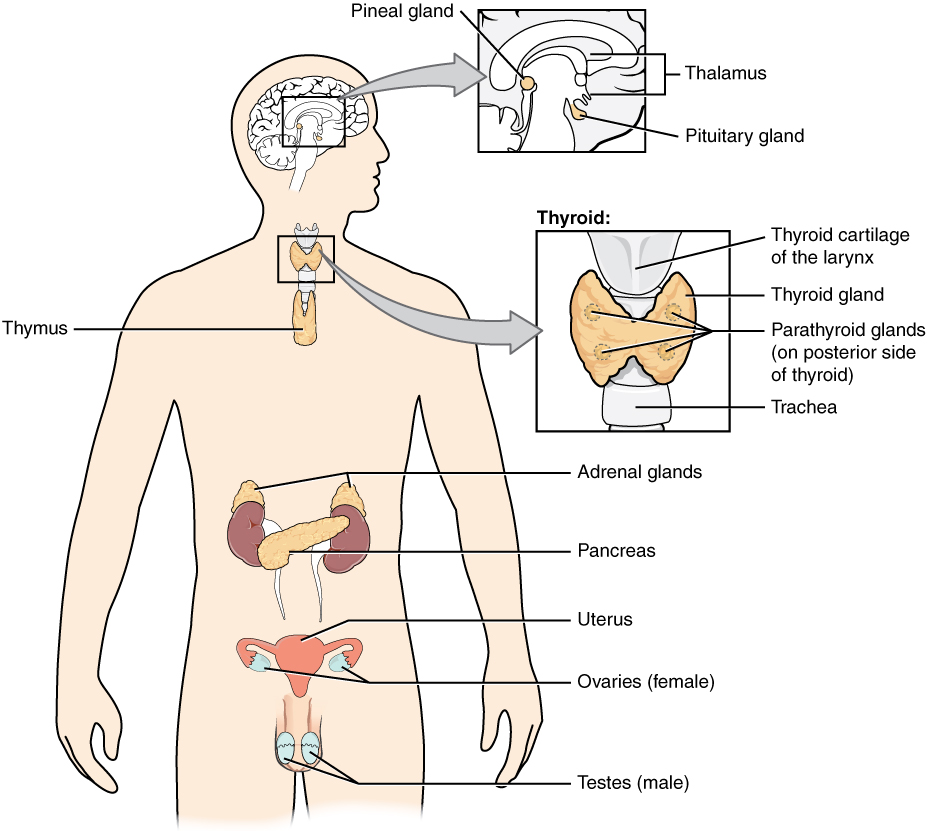

The endocrine system includes several glands, including the pineal, hypothalamus, pituitary, thyroid, parathyroid, and adrenal glands, as well as the pancreas, ovaries, and testes. See Figure 7.1 for an illustration of these organs of the endocrine system.[1]

Endocrine glands secrete hormones as chemical signaling. Hormones are transported via the bloodstream throughout the body, where they bind to receptors on target cells, triggering a characteristic response. This long-distance communication is the fundamental function of the endocrine system.

Pineal Gland

The pineal gland is a small cone-shaped structure that extends posteriorly from a ventricle of the brain. The pineal gland produces the hormone melatonin and secretes it directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, which carries it into the blood. Melatonin affects reproductive development and daily circadian rhythms.[2]

Thymus Gland

The thymus gland is located in the mediastinum. It is responsible for production of T lymphocytes for the body’s immune response.

Hypothalamus and Pituitary

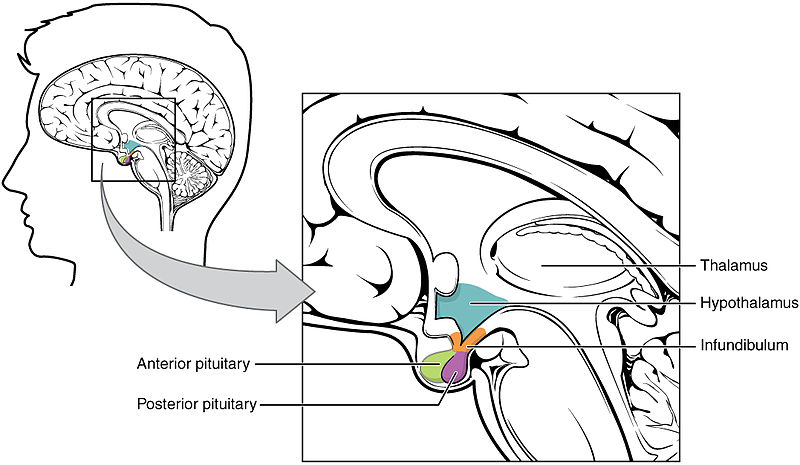

The hypothalamus can be viewed as the body’s control center. The hypothalamus connects to the pituitary gland by the stalk-like infundibulum. The pituitary gland is about the size of a pea and consists of an anterior and posterior lobe. Each secretes different hormones in response to signals from the hypothalamus. See Figure 7.2 for an illustration of the hypothalamus–pituitary complex.[3]

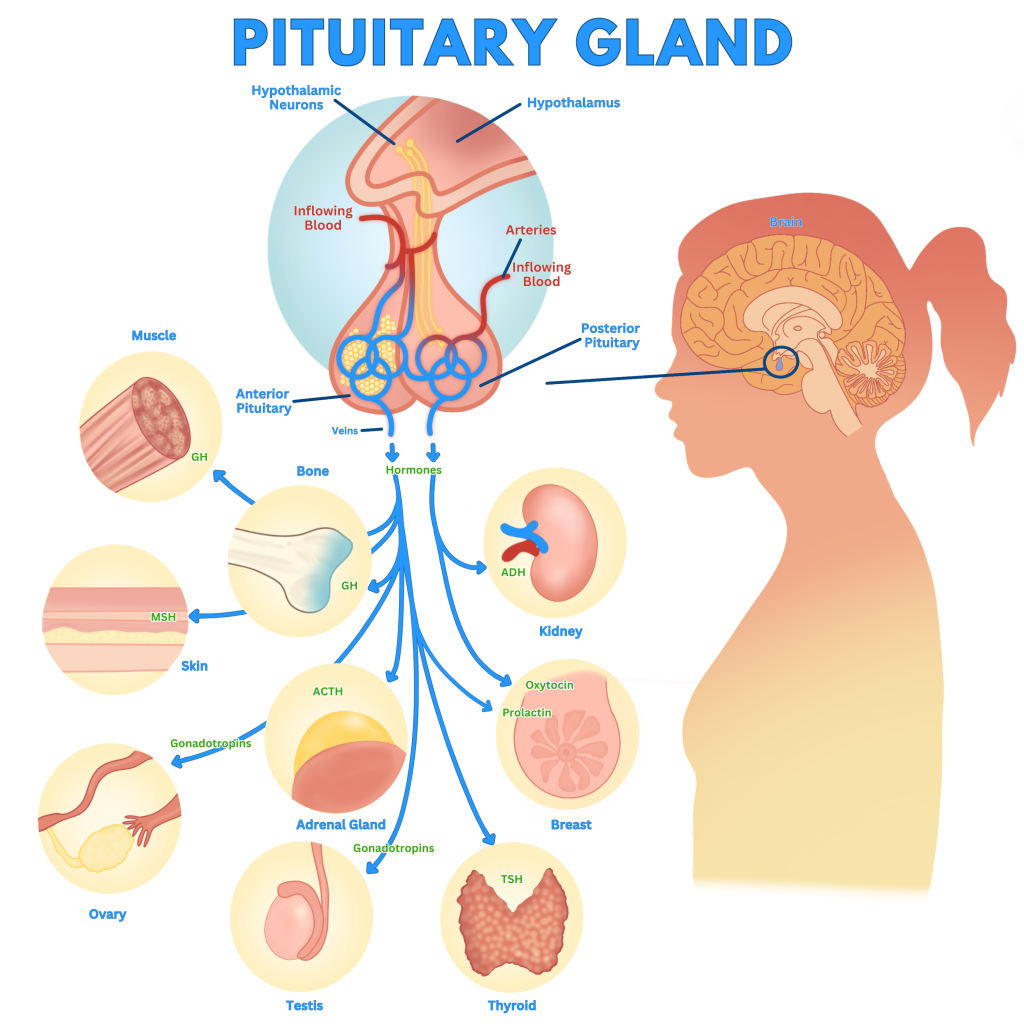

The hypothalamus–pituitary complex releases hormones that stimulate secretion of other hormones by other endocrine glands and also produce direct responses in target tissues. Its main function is to maintain a stable state called homeostasis. See Figure 7.3[4] for an illustration of the effects of the hormones released by the anterior and posterior pituitary glands.

Posterior Pituitary

The posterior pituitary gland secretes two hormones produced by the hypothalamus called oxytocin and antidiuretic hormone (ADH).

- Oxytocin stimulates labor contractions and lactation after delivery.

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) regulates blood osmolarity by targeting the kidneys to increase water reabsorption.

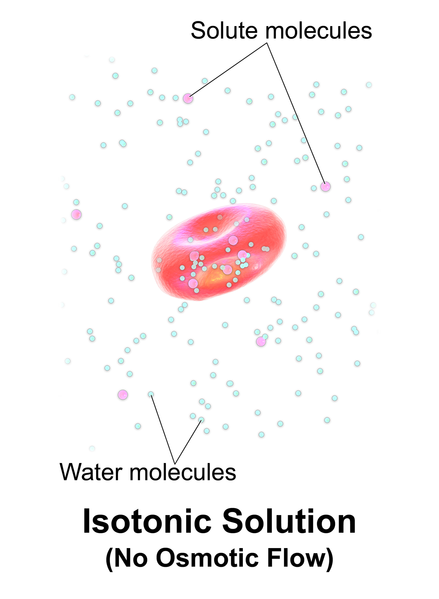

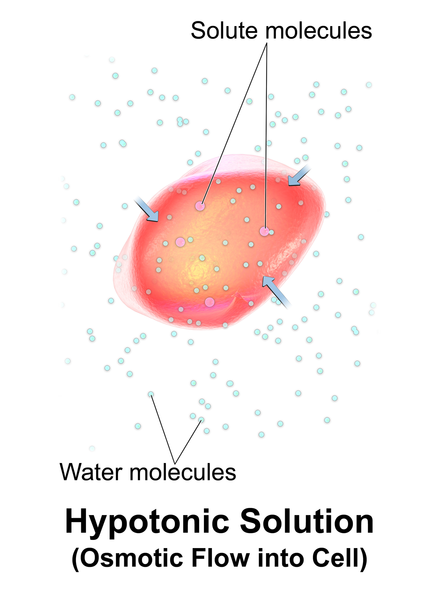

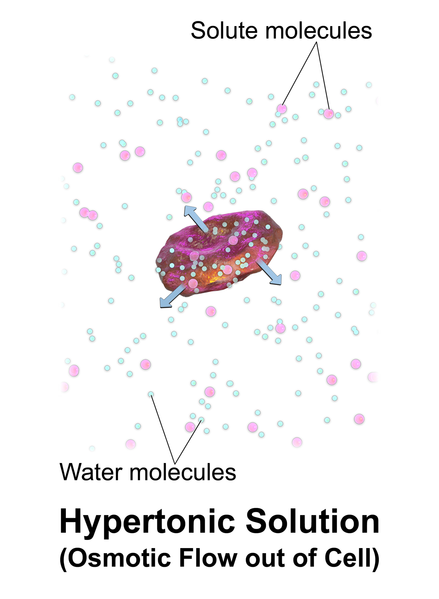

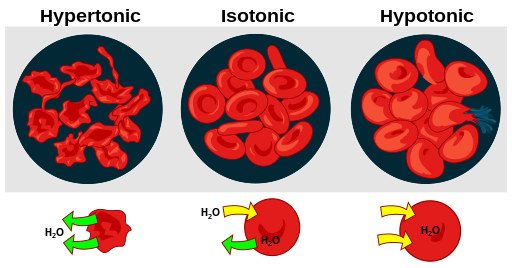

Blood osmolarity refers to the concentration of sodium and other solutes in the blood. Blood osmolarity levels change in response to fluid intake, salty food ingestion, head injuries, disease, and side effects of medications. Blood osmolarity is constantly monitored by osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus.

As blood osmolarity increases beyond normal levels, the posterior pituitary is stimulated to release ADH. For example, high blood osmolarity can occur if someone eats a very salty meal or becomes dehydrated from inadequate intake of fluids. Osmoreceptors sense the high blood osmolarity and trigger the sensation of thirst, while also stimulating the posterior pituitary to release ADH. ADH targets the kidneys to increase water reabsorption. As more water is reabsorbed by the kidneys and is returned to the blood, blood osmolarity decreases.

In contrast, if blood osmolarity decreases beyond normal levels, the release of ADH is inhibited, causing the kidney to increase the elimination of water and resulting in dilute urine.

Drugs can also affect the secretion of ADH or imitate its effects. For example, alcohol consumption inhibits the release of ADH, resulting in increased dilute urine production that can eventually lead to dehydration (and a hangover). Another example is vasopressin, a synthetic ADH medication that is used to treat very low blood pressure by causing the kidneys to retain water. Vasopressin is also used to treat a disease called diabetes insipidus (DI). People with DI have decreased amounts of ADH released by their pituitary, resulting in excessive amounts of dilute urine and severe dehydration.[5]

Anterior Pituitary

The anterior pituitary produces seven hormones:

- Growth hormone (GH): Promotes growth in children, helps maintain normal body structure in adults, and plays a role in metabolism in both children and adults.

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH): Stimulates thyroid hormone release by the thyroid gland. For example, if thyroid hormone levels in the blood are too low, the pituitary gland makes larger amounts of TSH to tell the thyroid to work harder. Conversely, if thyroid hormone levels are too high, the pituitary gland releases little or no TSH.

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH): Regulates the release of glucocorticoid hormone (cortisol) by the adrenal gland.

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH): Plays a role in sexual development and reproduction by affecting the function of the ovaries and testes.

- Luteinizing hormone (LH): Plays a role in sexual development in children and in women and triggers ovulation (the release of an egg from the ovary) during the menstrual cycle.

- Beta-endorphin: Possesses morphine-like effects and plays a role in pain management and natural reward circuits such as feeding, drinking, sex, and maternal behavior.

- Prolactin: Stimulates breast development and milk production in females.

Of the hormones released by the anterior pituitary, TSH, ACTH, FSH, and LH are referred to as tropic hormones because they turn on or off the function of other endocrine glands.

Negative Feedback Loop

TSH and ACTH levels in the blood are controlled by a negative feedback loop with the hypothalamus.

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH)

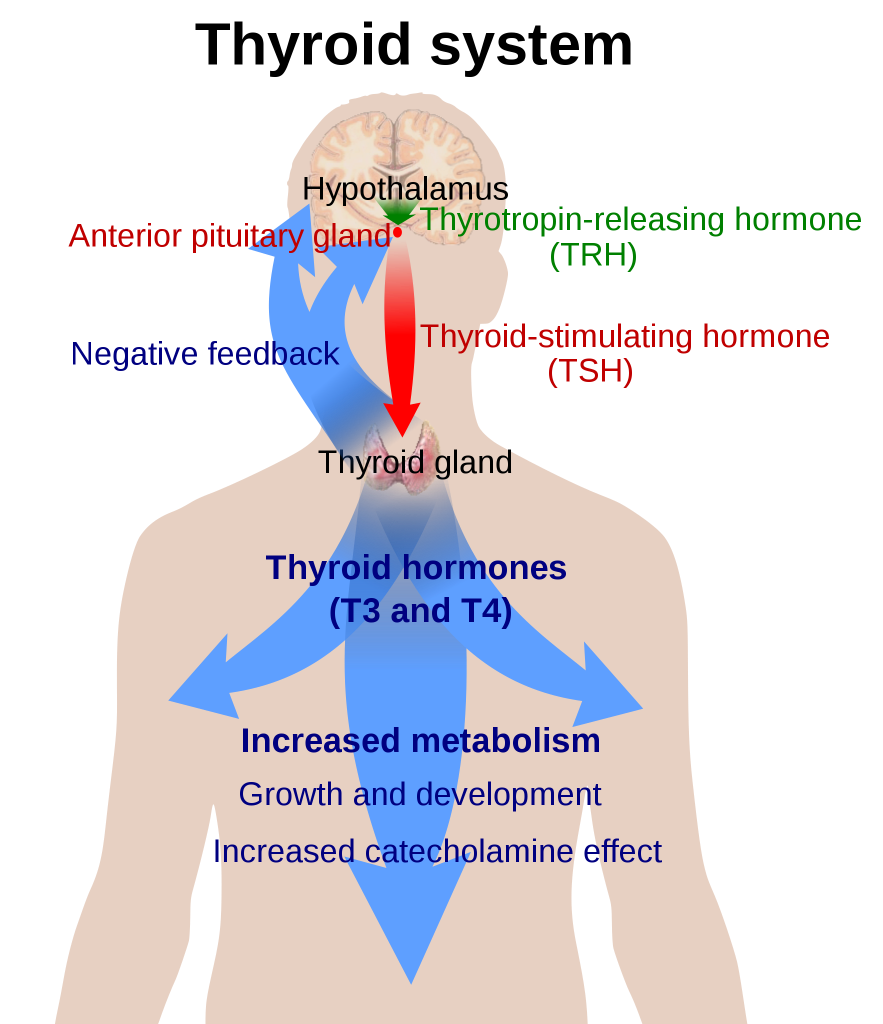

The hypothalamus stimulates the anterior pituitary with thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH). In response, the anterior pituitary stimulates the thyroid with thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). In response to TSH, the thyroid releases thyroid hormones called T3 and T4.

A negative feedback loop regulates the release of TSH by the anterior pituitary. For example, if the level of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) decreases in the bloodstream, the hypothalamus increases the secretion of TRH. TRH causes the anterior pituitary to increase the secretion of TSH. TSH stimulates the thyroid to increase production and release of T3 and T4. For this reason, a hypofunctioning thyroid is often diagnosed by elevated TSH levels. See Figure 7.4[6] for an image of the hypothalamus-anterior pituitary-thyroid axis and the corresponding negative feedback loop.

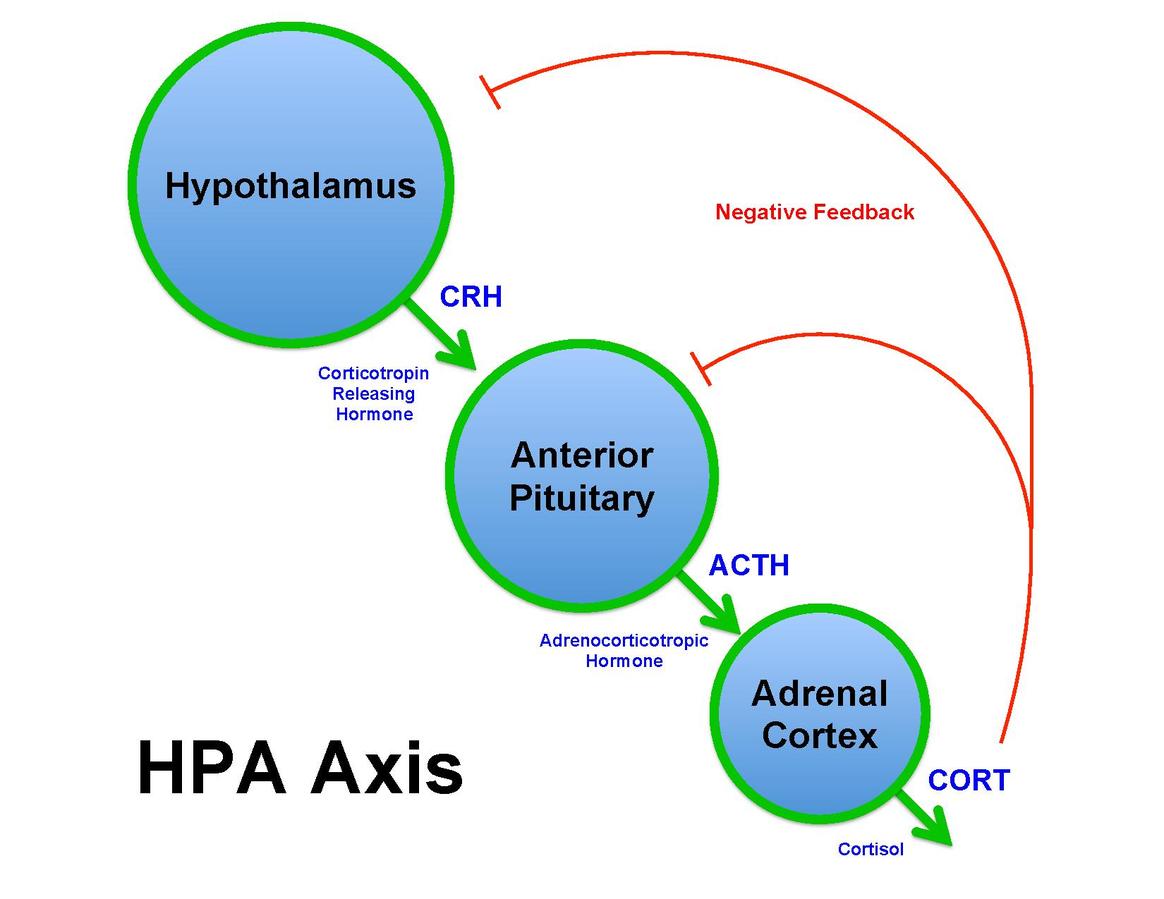

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH)

The hypothalamus stimulates the anterior pituitary with corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). In response, the anterior pituitary releases adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) to stimulate the adrenal cortex to release corticosteroids.[7]

A negative feedback loop regulates the release of ACTH by the anterior pituitary. For example, if levels of corticosteroids decrease in the bloodstream, the hypothalamus increases the secretion of CRH, causing the anterior pituitary to increase the secretion of ACTH. This is often referred to as the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. See Figure 7.5[8] for an image of the HPA axis and negative feedback loop.

Thyroid Gland

The thyroid gland is a butterfly-shaped endocrine gland located in the neck, just below the larynx. It helps to regulate metabolic processes in the body by producing and releasing thyroid hormones.

The thyroid releases these two hormones:

- Thyroxine (T4)

- Triiodothyronine (T3)

Both T3 and T4 are iodine-containing compounds. These hormones are critical for regulating the body’s basal metabolic rate (BMR), the rate at which the body burns energy at rest.

The primary functions of thyroid hormones T3 and T4 include the following:

- Regulation of Metabolism: Control how the body uses energy and oxygen, impacting processes such as digestion, heart rate, and temperature regulation.

- Growth and Development: Impact normal growth and development, particularly in children and infants. They influence the growth of bones, as well as the development of the brain and the nervous system.

- Temperature Regulation: Regulate body temperature by controlling heat production and heat dissipation mechanisms.

- Energy Production: Involved in the conversion of food into energy. They affect the breakdown of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins for energy use.

- Heart Rate and Blood Pressure: Influence heart rate and the strength of heart contractions, helping to maintain cardiovascular function.

- Brain Function: Play a role in cognitive function, mood regulation, and mental alertness. For example, hypothyroidism (low thyroid hormone levels) can lead to cognitive and emotional changes.

The production and release of thyroid hormones are regulated by the hypothalamus-pituitary complex discussed earlier in this chapter.

Parathyroid Glands

Four small masses of tissue are embedded on the surface of the thyroid gland called parathyroid glands.

Parathyroid glands secrete parathyroid hormone (PTH). PTH maintains homeostasis between calcium and phosphorus via a negative feedback loop. Calcium and phosphorus have an inverse relationship, meaning if phosphorus levels rise, calcium levels will drop.

Adrenal Glands

The adrenal glands are small glands located on top of each kidney. There are two parts to the adrenal gland called the adrenal cortex and the adrenal medulla. Each part has distinct functions:

- Adrenal Cortex: The adrenal cortex is responsible for producing a group of steroid hormones known as corticosteroids. Corticosteroids can be further divided into three categories called mineralocorticoids, glucocorticoids, and androgens.

- Mineralocorticoids: The principal mineralocorticoid is aldosterone. Aldosterone regulates electrolyte and fluid balance in the body by controlling sodium and potassium levels in the blood. It is a key component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) in which specialized cells of the kidneys secrete renin in response to low blood volume or low blood pressure. Renin then catalyzes angiotensinogen to the hormone Angiotensin I. Angiotensin I is converted to Angiotensin II by the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). Angiotensin II stimulates the release of aldosterone. Many cardiac medications target the effects of aldosterone and the RAAS system. For example, ACE inhibitors block the production of Angiotensin II and are used to reduce high blood pressure.

- Glucocorticoids: The principal glucocorticoid is cortisol. Cortisol is the most important glucocorticoid because it plays a crucial role in metabolism, immune response, and the body’s response to stress. Cortisol helps regulate blood sugar levels, suppress inflammation, and manage the stress response.

- Androgens: These are secreted in minimal amounts in both sexes by the adrenal cortex, but their effect is usually masked by the hormones from the testes and ovaries.

- Adrenal Medulla: The adrenal medulla is responsible for producing epinephrine and norepinephrine. These hormones play a central role in the body’s “fight or flight” response to stress that is triggered by the sympathetic nervous system. Epinephrine and norepinephrine prepare the body for action by increasing heart rate, dilating airways, and redirecting blood flow to muscles, among other effects.

View a supplementary YouTube video[9] on ACTH and the adrenal gland:

Ovaries and Testes

In females, the ovaries produce ova (eggs), and in males, the testes produce sperm. Ovaries and testes also secrete hormones.

Ovaries secrete estrogen and progesterone[10]:

- At the onset of puberty, estrogen promotes the development of breasts and the maturation of the uterus.

- Progesterone causes the uterine lining to thicken in preparation for pregnancy.

- Together, progesterone and estrogen are responsible for the changes that occur in the uterus during the female menstrual cycle.

Testes secrete testosterone. At the onset of puberty, testosterone is responsible for the following actions[11]:

- The growth and development of the male reproductive structures

- Increased skeletal and muscular growth

- Enlargement of the larynx accompanied by voice changes

- Growth and distribution of body hair

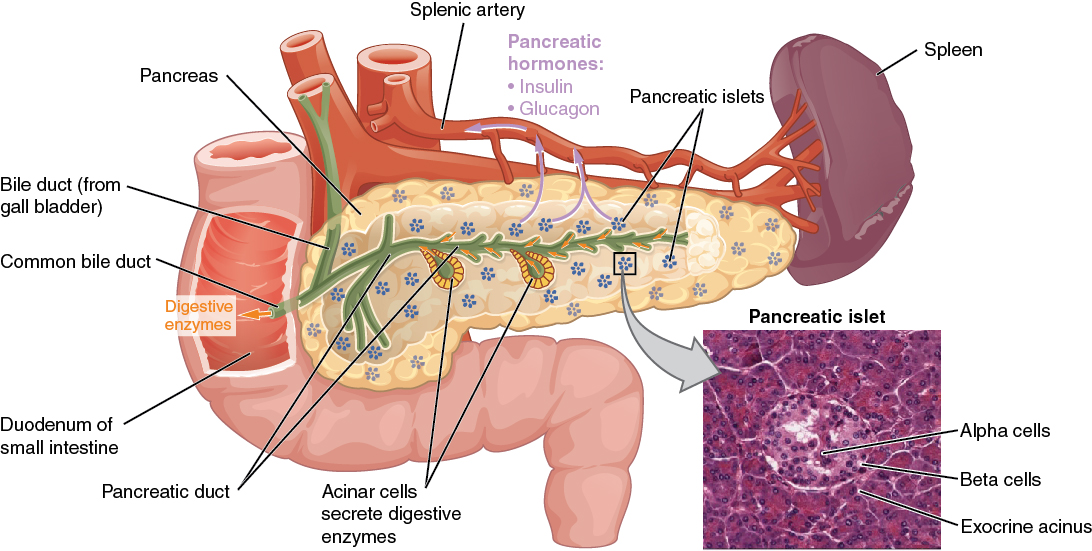

Pancreas

The pancreas is a long, flat gland that lies behind the stomach. The pancreas serves two roles called exocrine and endocrine. The exocrine role refers to the release of digestive enzymes called amylase and lipase that help to digest food. The endocrine role refers to the production of glucagon and insulin by clusters of cells called islet cells to regulate blood glucose levels and keep them within a healthy range. See Figure 7.6[12] for an illustration of the pancreas.

The islet cells in the pancreas include alpha, beta, and delta cells:

- Alpha Cells: Alpha cells secrete a hormone called glucagon. The primary function of glucagon is to increase blood glucose levels. When blood glucose levels drop (such as between meals or during exercise), glucagon is released.

- Beta Cells: Beta cells secrete insulin. Insulin facilitates the uptake of glucose by cells from the bloodstream, thus reducing blood glucose levels.

- Delta Cells: Delta cells secrete somatostatin. Somatostatin slows down the secretion of insulin and glucagon when needed to maintain blood glucose homeostasis.

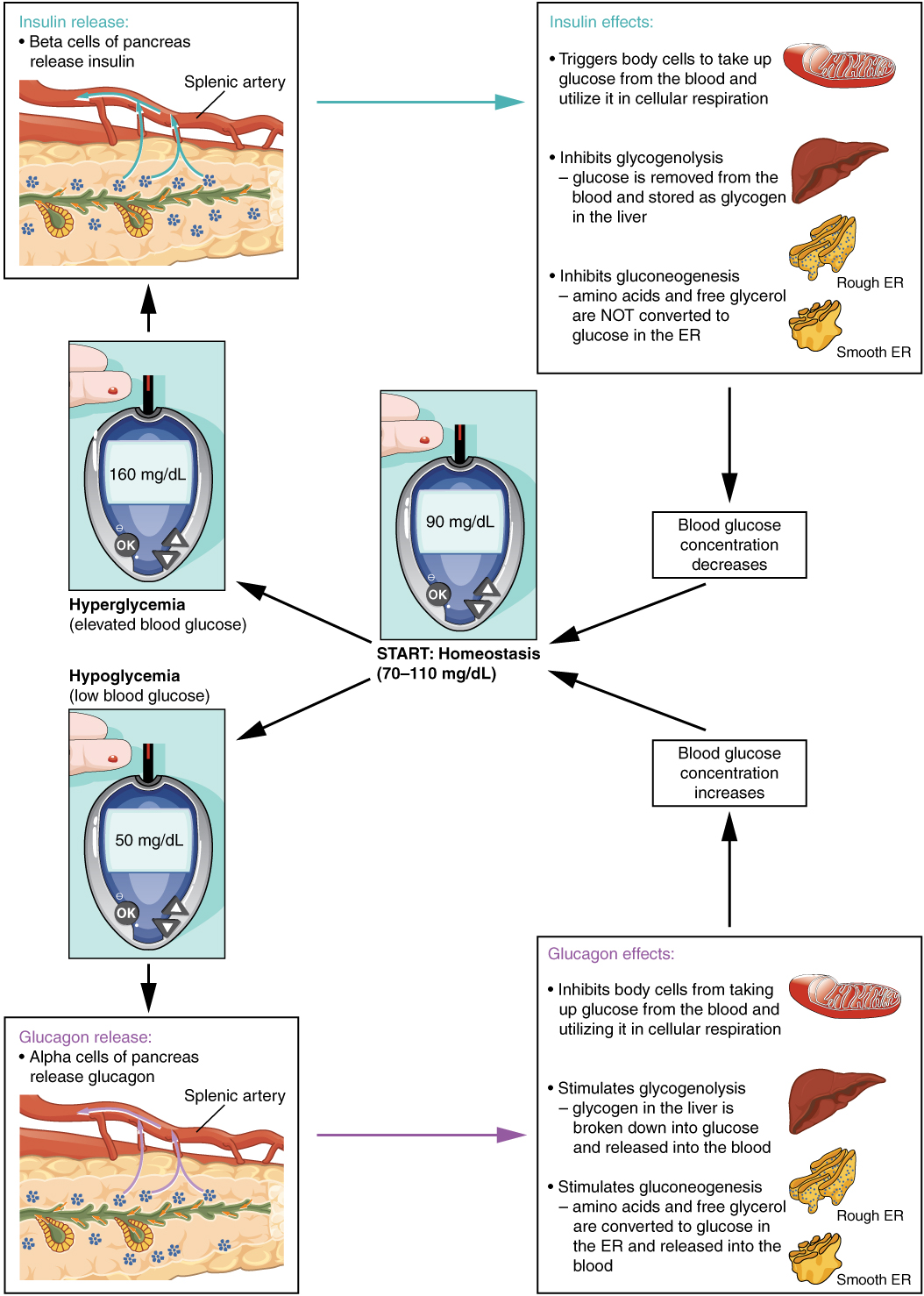

Regulation of Blood Glucose Levels by Insulin and Glucagon

Glucose is the primary fuel for all body cells and the only fuel source for the brain. The digestive system breaks down carbohydrates into glucose, where it is absorbed into the bloodstream. Glucose is taken up by cells for fuel. Glucose that is not immediately used by cells is stored in the liver and muscles as glycogen. It is also converted into triglycerides and stored in adipose (fat) tissue.

Blood glucose levels are maintained by healthy individuals’ bodies between 70 mg/dL and 110 mg/dL. Receptors located in the pancreas sense blood glucose levels, and the islet cells secrete glucagon or insulin to maintain normal blood glucose levels. If blood glucose levels rise above this range, insulin is released, which stimulates body cells to take in glucose from the blood. If blood glucose levels drop below this range, glucagon is released, which stimulates cells to release glucose from the stored glycogen into the bloodstream.

Glucagon

When blood glucose levels drop between meals or during exercise, the alpha cells secrete glucagon, which increases blood glucose levels by stimulating the following actions:

- Within cells, it inhibits the uptake of glucose.

- It stimulates the liver to convert stored glycogen into glucose and release it into the bloodstream, a process called glycogenolysis.

- It stimulates the liver to take up amino acids from the blood and converts them into glucose, a process called gluconeogenesis.

- It stimulates the breakdown of stored triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol, a process called lipolysis. Glycerol travels to the liver, where it is converted into glucose. This is also a form of gluconeogenesis.

Insulin

The presence of food in the intestine triggers the beta cells in the pancreas to produce and secrete insulin. As blood glucose levels continue to rise as nutrients are absorbed into the bloodstream, insulin continues to be released and stimulates the following actions:

- It stimulates the uptake of glucose by cells by triggering the movement of glucose transporters to the cell membranes, which move glucose into the interior of cells for energy. Glycolysis is the first step in the breakdown of glucose to extract energy for cellular metabolism.

- It stimulates the liver to convert excess blood glucose into glycogen for storage. It also inhibits glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis.

- Excess glucose is synthesized into triglycerides, a process called lipogenesis.

The secretion of insulin and glucagon by the pancreas is regulated through a negative feedback loop. As glucose levels decrease in the bloodstream, insulin release is inhibited. Conversely, as glucose levels rise in the bloodstream, glucagon release is inhibited. See Figure 7.7[13] for an illustration of the homeostatic regulation of blood glucose levels.

Media Attributions

- 1801_The_Endocrine_System

- 1806_The_Hypothalamus-Pituitary_Complex

- Pituitary Gland by Meredith Pomietlo

- Thyroid_system.svg

- Brian_M_Sweis_HPA_Axis_Diagram_2012.pdf

- 1820_The_Pancreas

- 1822_The_Homostatic_Regulation_of_Blood_Glucose_Levels (1)

- “1801 The Endocrine System.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). Endocrine glands & their function. https://training.seer.cancer.gov/anatomy/endocrine/glands/ ↵

- “1806 The Hypothalamus-Pituitary Complex.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- "Pituitary Gland" by Meredith Pomietlo is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Thyroid_system.svg” by Mikael Häggström is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Brian_M_Sweis_HPA_Axis_Diagram_2012.pdf” by BrianMSweis is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Forciea, B. (2015, May 12). Anatomy and physiology: Endocrine system: ACTH (Adrenocorticotropin hormone) V2.0 [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video reused with permission. https://youtu.be/4m7XflJzm2w. ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). Gonads. https://training.seer.cancer.gov/anatomy/endocrine/glands/gonads.html ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). Gonads. https://training.seer.cancer.gov/anatomy/endocrine/glands/gonads.html ↵

- “1820 The Pancreas.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “1822 The Homeostatic Regulation of Blood Glucose Levels.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

Before discussing specific procedures related to facilitating bowel and bladder function, let’s review basic concepts related to urinary and bowel elimination. When facilitating alternative methods of elimination, it is important to understand the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal and urinary systems, as well as the adverse effects of various conditions and medications on elimination. Use the information below to review information about these topics.

For more information about the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal system and medications used to treat diarrhea and constipation, visit the "Gastrointestinal" chapter of the Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook.

For more information about the anatomy and physiology of the kidneys and diuretic medications used to treat fluid overload, visit the "Cardiovascular and Renal System" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook.

For more information about applying the nursing process to facilitate elimination, visit the "Elimination" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Urinary Elimination Devices

This section will focus on the devices used to facilitate urinary elimination. Urinary catheterization is the insertion of a catheter tube into the urethral opening and placing it in the neck of the urinary bladder to drain urine. There are several types of urinary elimination devices, such as indwelling catheters, intermittent catheters, suprapubic catheters, and external devices. Each of these types of devices is described in the following subsections.

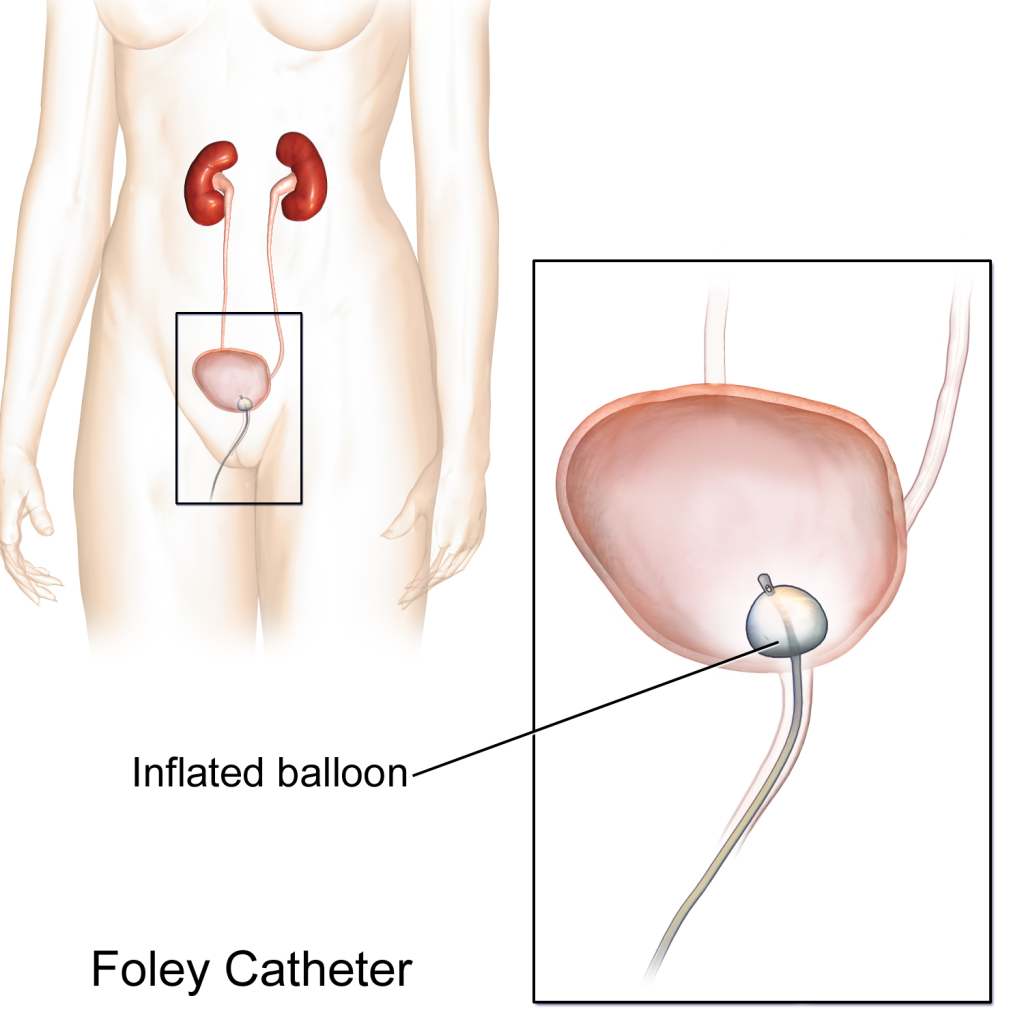

Indwelling Catheter

An indwelling catheter, often referred to as a “Foley catheter,” refers to a urinary catheter that remains in place after insertion into the bladder for the continual collection of urine. It has a balloon on the insertion tip to maintain placement in the neck of the bladder. The other end of the catheter is attached to a drainage bag for the collection of urine. See Figure 21.1[1] for an illustration of the anatomical placement of an indwelling catheter in the bladder neck.

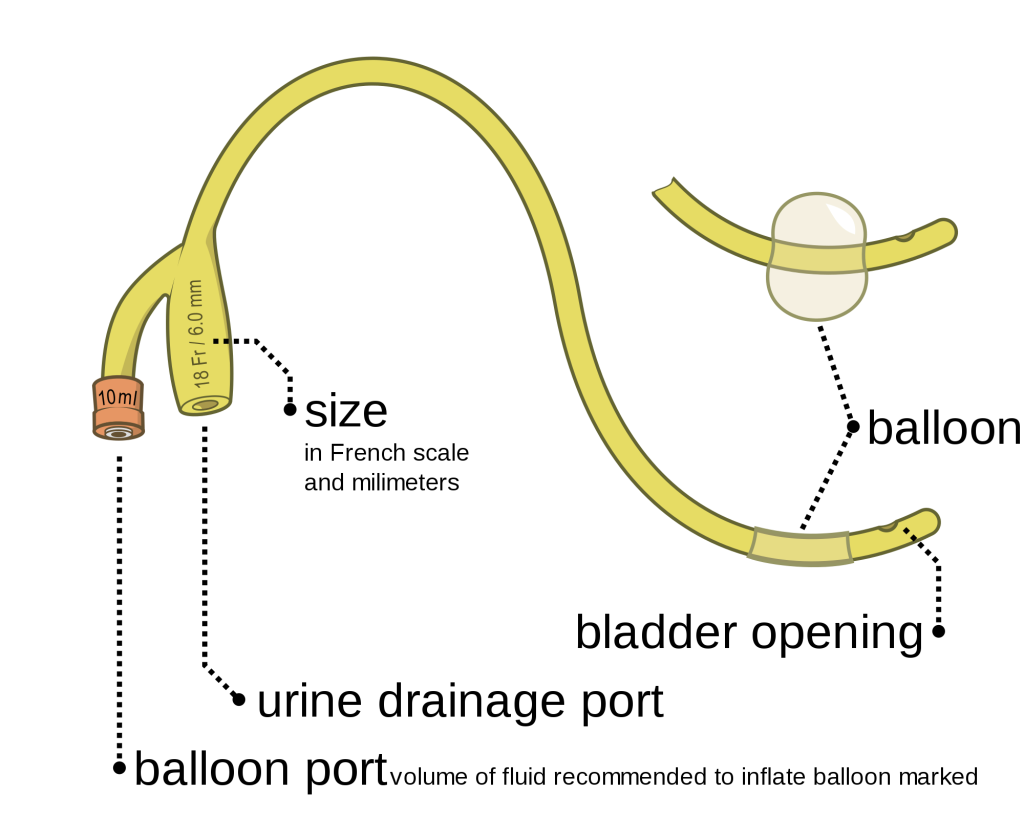

The distal end of an indwelling catheter has a urine drainage port that is connected to a drainage bag. The size of the catheter is marked at this end using the French catheter scale. A balloon port is also located at this end, where a syringe is inserted to inflate the balloon after it is inserted into the bladder. The balloon port is marked with the amount of fluid required to fill the balloon. See Figure 21.2[2] for an image of the parts of an indwelling catheter.

Catheters have different sizes, with the larger the number indicating a larger diameter of the catheter. See Figure 21.3[3] for an image of the French catheter scale.

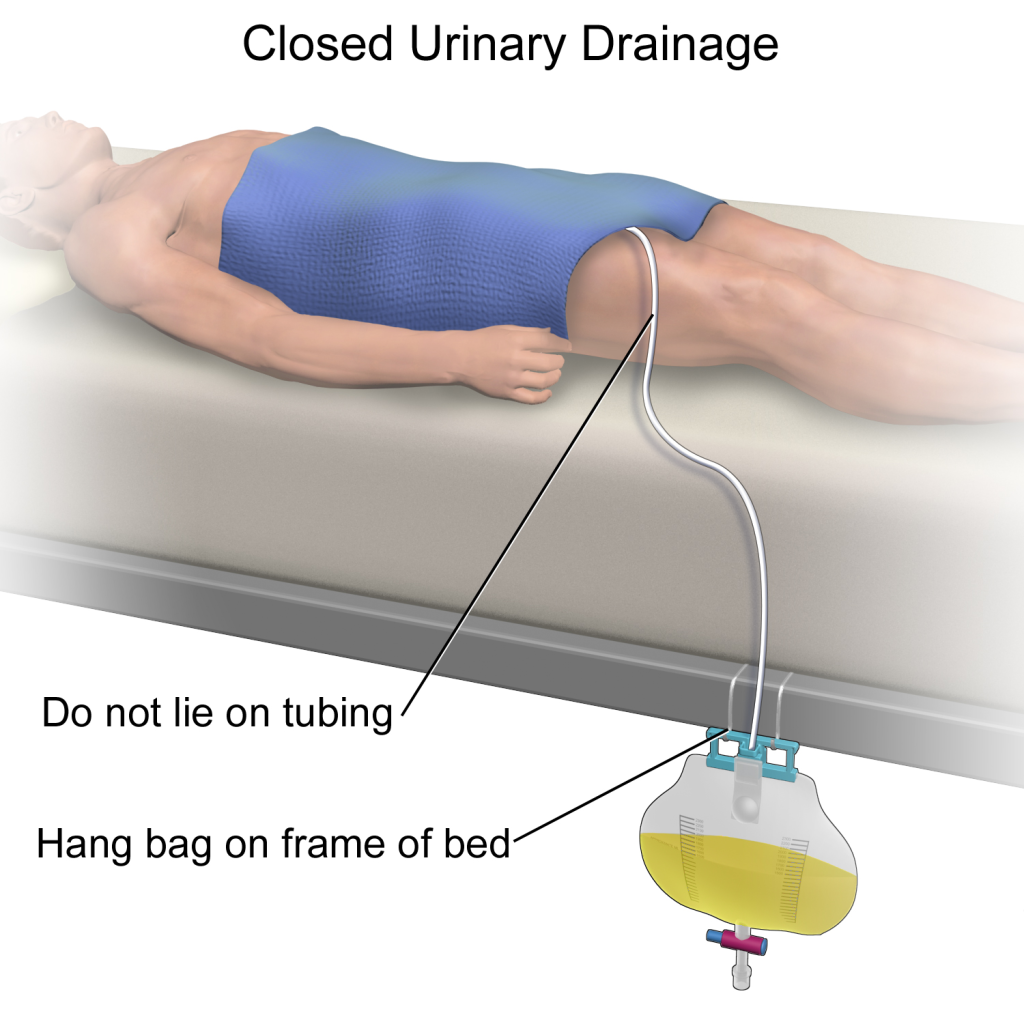

There are two common types of bags that may be attached to an indwelling catheter. During inpatient or long-term care, larger collection bags that can hold up to two liters of fluid are used. See Figure 21.4[4] for an image of a typical collection bag attached to an indwelling catheter. These bags should be emptied when they are half to two-thirds full to prevent traction on the urethra from the bag. Additionally, the collection bag should always be placed below the level of the patient’s bladder so that urine flows out of the bladder and urine does not inadvertently flow back into the bladder. Ensure the tubing is not coiled, kinked, or compressed so that urine can flow unobstructed into the bag. Slack should be maintained in the tubing to prevent injury to the patient's urethra. To prevent the development of a urinary tract infection, the bag should not be permitted to touch the floor.

See Figure 21.5[5] for an illustration of the placement of the urine collection bag when the patient is lying in bed.

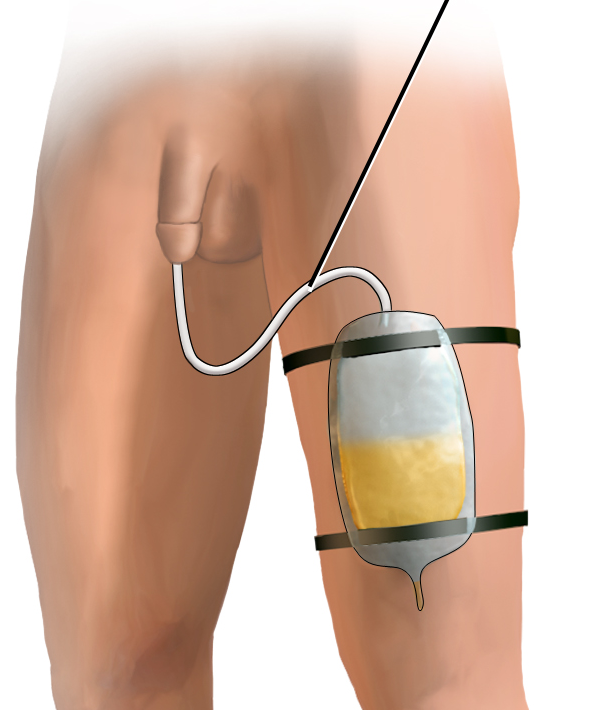

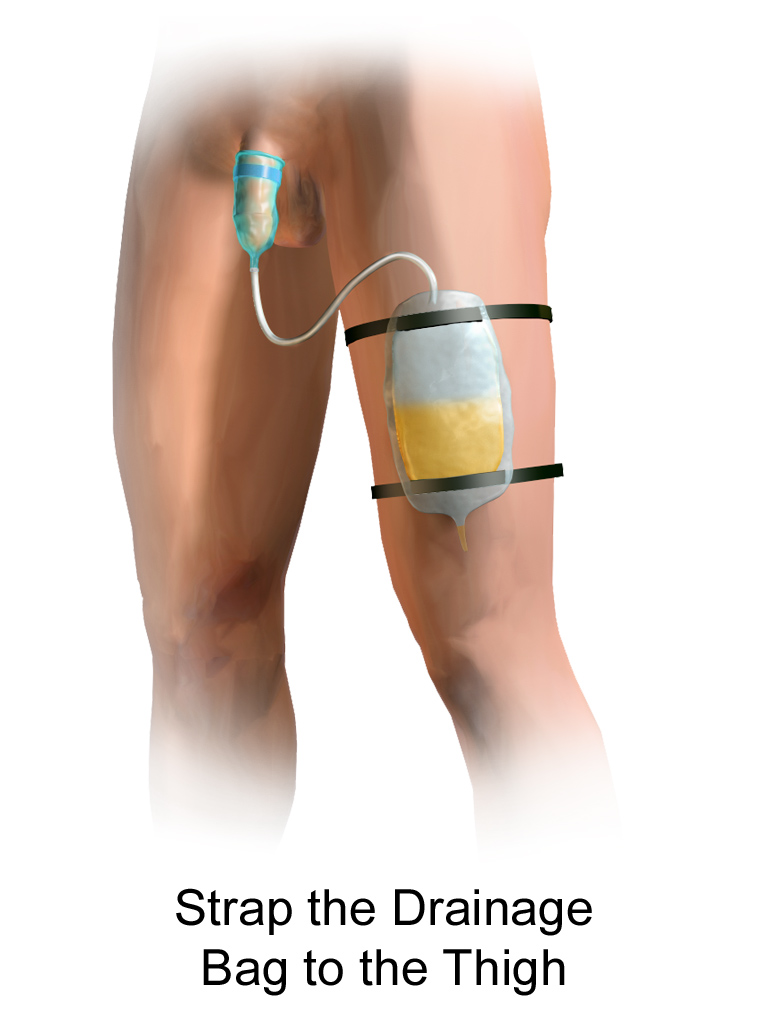

A second type of urine collection bag is a leg bag. Leg bags provide discretion when the patient is in public because they can be worn under clothing. However, leg bags are small and must be emptied more frequently than those used during inpatient care. Figure 21.6[6] for an image of leg bag and Figure 21.7[7] for an illustration of an indwelling catheter attached to a leg bag.

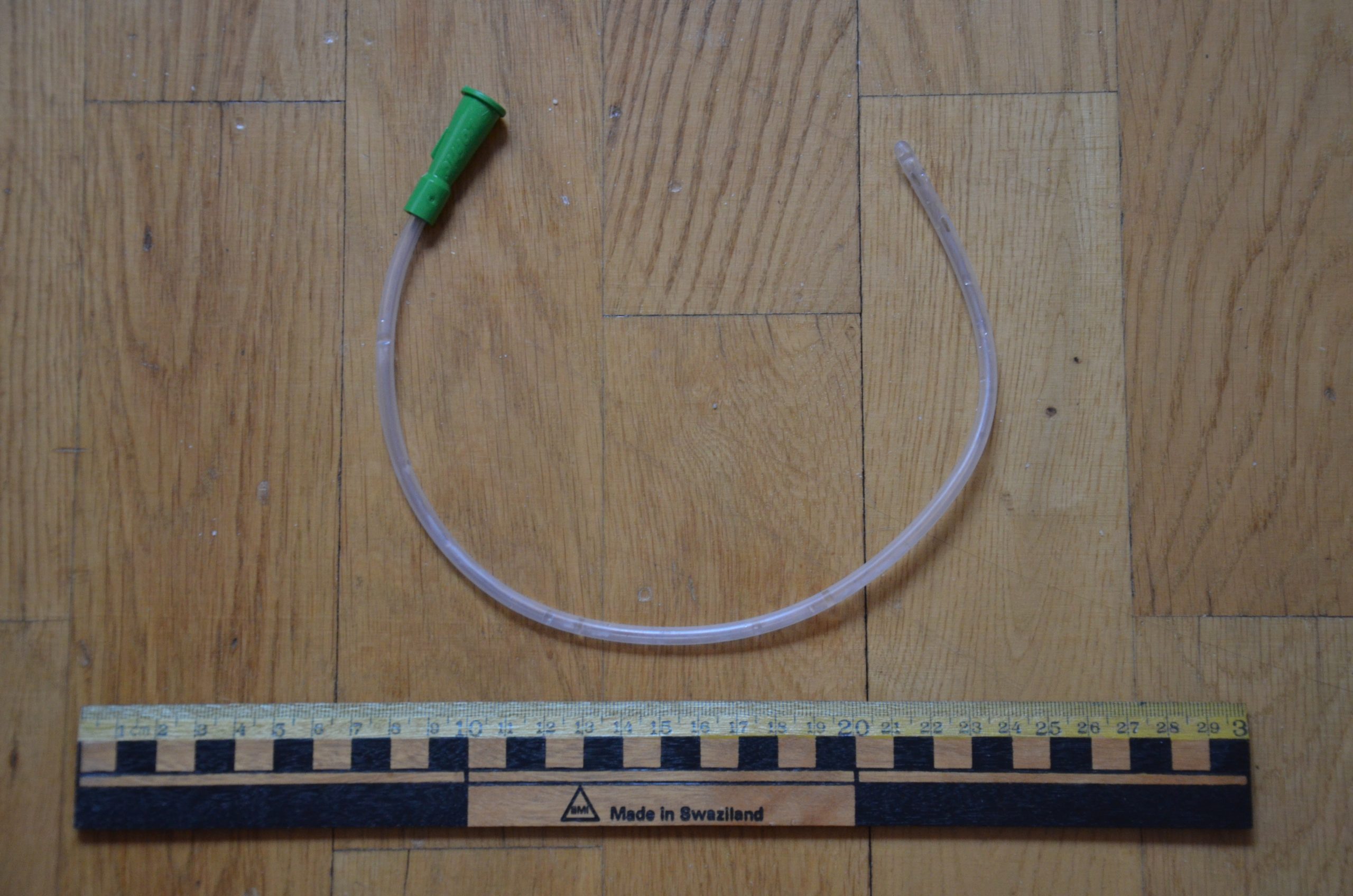

Straight Catheter

A straight catheter is used for intermittent urinary catheterization. The catheter is inserted to allow for the flow of urine and then immediately removed, so a balloon is not required at the insertion tip. See Figure 21.8[8] for an image of a straight catheter. Intermittent catheterization is used for the relief of urinary retention. It may be performed once, such as after surgery when a patient is experiencing urinary retention due to the effects of anesthesia, or performed several times a day to manage chronic urinary retention. Some patients may also independently perform self-catheterization at home to manage chronic urinary retention caused by various medical conditions. In some situations, a straight catheter is also used to obtain a sterile urine specimen for culture when a patient is unable to void into a sterile specimen cup. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), intermittent catheterization is preferred to indwelling urethral catheters whenever feasible because of decreased risk of developing a urinary tract infection.[9]

Other Types of Urinary Catheters

Coude Catheter Tip

Coude catheter tips are curved to follow the natural curve of the urethra during catheterization. They are often used when catheterizing male patients with enlarged prostate glands. See Figure 21.9[10] for an example of a urinary catheter with a coude tip. During insertion, the tip of the coude catheter must be pointed anteriorly or it can cause damage to the urethra. A thin line embedded in the catheter provides information regarding orientation during the procedure; maintain the line upwards to keep it pointed anteriorly.

Irrigation Catheter

Irrigation catheters are typically used after prostate surgery to flush the surgical area. These catheters are larger in size to allow for irrigation of the bladder to help prevent the formation of blood clots and to flush them out. See Figure 21.10[11] for an image comparing a larger 20 French catheter (typically used for irrigation) to a 14 French catheter (typically used for indwelling catheters).

Suprapubic Catheters

Suprapubic catheters are surgically inserted through the abdominal wall into the bladder. This type of catheter is typically inserted when there is a blockage within the urethra that does not allow the use of a straight or indwelling catheter. Suprapubic catheters may be used for a short period of time for acute medical conditions or may be used permanently for chronic conditions. See Figure 21.11[12] for an image of a suprapubic catheter. The insertion site of a suprapubic catheter must be cleaned regularly according to agency policy with appropriate steps to prevent skin breakdown.

Male Condom Catheter

A condom catheter is a noninvasive device used for males with incontinence. It is placed over the penis and connected to a drainage bag. This device protects and promotes healing of the skin around the perineal area and inner legs and is used as an alternative to an indwelling urinary catheter. See Figure 21.12[13] for an image of a condom catheter and Figure 21.13[14] for an illustration of a condom catheter attached to a leg bag.

Female External Urinary Catheter

Female external urinary catheters (FEUC) have been recently introduced into practice to reduce the incidence of catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) in women.[15] The external female catheter device is made of a purewick material that is placed externally over the female’s urinary meatus. The wicking material is attached to a tube that is hooked to a low-suction device. When the wick becomes saturated with urine, it is suctioned into a drainage canister. Preliminary studies have found that utilizing the FEUC device reduced the risk for CAUTI.[16],[17]

View these supplementary YouTube videos on female external urinary catheters:

Students demonstrate use of PureWick female external catheter[18]

How to use the use the PureWick - a female external catheter[19]

A catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) is a common, life-threatening complication caused by indwelling urinary catheters. The development of a CAUTI is associated with patients’ increased length of stay in the hospital, resulting in additional hospital costs and a higher risk of death. It is estimated that 17% to 69% of CAUTI cases are preventable, meaning that up to 380,000 infections and 9,000 patient deaths per year related to CAUTI can be prevented with appropriate nursing measures.[20]

Nurses can save lives, prevent harm, and lower health care costs by following interventions outlined in the document created by the American Nurses Association titled Streamlined Evidence-Based RN Tool: Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) Prevention. Review the entire tool in the box provided below. Key interventions include the following:

- Ensure the patient meets CDC-approved indications prior to inserting an indwelling catheter. If the patient does not meet the approved indications, contact the provider and advocate for an alternative method to facilitate elimination.

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), appropriate indications for inserting an indwelling urinary catheter include the following[21]:

- Urinary retention or bladder outlet obstruction

- Hourly monitoring of urinary output in critically ill patients

- Perioperative use for selected surgeries

- Healing of open sacral and perineal wounds in patients with urinary incontinence

- Prolonged immobilization

- End-of-life care[22]

- Inappropriate reasons for inserting an indwelling urinary catheter include the following:

- Substitution of nursing care for a patient or resident with incontinence

- A means for obtaining a urine culture when a patient can voluntarily void

- Prolonged postoperative care without appropriate indications[23]

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), appropriate indications for inserting an indwelling urinary catheter include the following[21]:

- After an indwelling urinary catheter is inserted, assess the patient daily to determine if the patient still meets the CDC criteria for an indwelling catheter and document the findings. If the patient no longer meets the approved criteria, follow agency policy for removal.

- When an indwelling catheter is in place, prevent CAUTI by following the maintenance steps outlined by the CDC.

- Continually monitor for signs of a CAUTI and report concerns to the health care provider.[24]

- Signs and symptoms of CAUTI to urgently report to the health care provider include fever greater than 38 degrees Celsius, change in mental status such as confusion or lethargy, chills, malodorous urine, and suprapubic or flank pain. Flank pain can be assessed by assisting the patient to a sitting or side-lying position and percussing the costovertebral areas.[25]

Read a nurse-driven, evidence-based PDF tool to prevent CAUTI from the American Nurses Association[26]: Streamlined Evidence-Based RN Tool: Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) Prevention

Safely and accurately placing an indwelling urinary catheter poses several challenges that require the nurse to use clinical judgment. Challenges can include anatomical variations in a specific patient, medical conditions affecting patient positioning, and maintaining sterility of the procedure with confused or agitated patients. See the checklists on Foley Catheter Insertion (Male) and Foley Catheter Insertion (Female) for detailed instructions.

Nursing interventions to prevent the development of a catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) on insertion include the following[27]:

- Determine if insertion of an indwelling catheter meets CDC guidelines.

- Select the smallest-sized catheter that is appropriate for the patient, typically a 14 French.

- Obtain assistance as needed to facilitate patient positioning, visualization, and insertion. Many agencies require two nurses for the insertion of indwelling catheters.

- Perform perineal care before inserting a urinary catheter and regularly thereafter.

- Perform hand hygiene before and after insertion, as well as during any manipulation of the device or site.

- Maintain strict aseptic technique during insertion and use sterile gloves and equipment.

- Inflate the balloon after insertion per manufacturer instructions. It is not recommended to preinflate the balloon prior to insertion.

- Properly secure the catheter after insertion to prevent tissue damage.

- Keep the drainage bag below the bladder but not resting on the floor.

- Check the system to ensure there are no kinks or obstructions to urine flow.

- Provide routine hygiene of the urinary meatus during daily bathing and cleanse the perineal area after every bowel movement. In uncircumcised males, gently retract the foreskin, cleanse the meatus, and then return the foreskin to the original position. Do not cleanse the periurethral area with antiseptics after the catheter is in place.[28] To avoid contaminating the urinary tract, always clean by wiping away from the urinary meatus.

- Empty the collection bag regularly using a separate, clean collecting container for each patient. Avoid splashing and prevent contact of the drainage spigot with the nonsterile collecting container or other surfaces. Never allow the bag to touch the floor.[29],[30]

Video Review of Thompson Rivers University's Urinary Catheterization:

Safely and accurately placing an indwelling urinary catheter poses several challenges that require the nurse to use clinical judgment. Challenges can include anatomical variations in a specific patient, medical conditions affecting patient positioning, and maintaining sterility of the procedure with confused or agitated patients. See the checklists on Foley Catheter Insertion (Male) and Foley Catheter Insertion (Female) for detailed instructions.

Nursing interventions to prevent the development of a catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) on insertion include the following[33]:

- Determine if insertion of an indwelling catheter meets CDC guidelines.

- Select the smallest-sized catheter that is appropriate for the patient, typically a 14 French.

- Obtain assistance as needed to facilitate patient positioning, visualization, and insertion. Many agencies require two nurses for the insertion of indwelling catheters.

- Perform perineal care before inserting a urinary catheter and regularly thereafter.

- Perform hand hygiene before and after insertion, as well as during any manipulation of the device or site.

- Maintain strict aseptic technique during insertion and use sterile gloves and equipment.

- Inflate the balloon after insertion per manufacturer instructions. It is not recommended to preinflate the balloon prior to insertion.

- Properly secure the catheter after insertion to prevent tissue damage.

- Keep the drainage bag below the bladder but not resting on the floor.

- Check the system to ensure there are no kinks or obstructions to urine flow.

- Provide routine hygiene of the urinary meatus during daily bathing and cleanse the perineal area after every bowel movement. In uncircumcised males, gently retract the foreskin, cleanse the meatus, and then return the foreskin to the original position. Do not cleanse the periurethral area with antiseptics after the catheter is in place.[34] To avoid contaminating the urinary tract, always clean by wiping away from the urinary meatus.

- Empty the collection bag regularly using a separate, clean collecting container for each patient. Avoid splashing and prevent contact of the drainage spigot with the nonsterile collecting container or other surfaces. Never allow the bag to touch the floor.[35],[36]

Video Review of Thompson Rivers University's Urinary Catheterization:

When preparing to insert an indwelling urinary catheter, it is important to use the nursing process to plan and provide care to the patient. Begin by assessing the appropriateness of inserting an indwelling catheter according to CDC criteria as discussed in the “Preventing CAUTI” section of this chapter. Determine if alternative measures can be used to facilitate elimination and address any concerns with the prescribing provider before proceeding with the provider order.

Subjective Assessment

In addition to verifying the appropriateness of the insertion of an indwelling catheter according to CDC recommendations, it is also important to assess for any conditions that may interfere with the insertion of a urinary catheter when feasible. See suggested interview questions prior to inserting an indwelling catheter and their rationale in Table 21.8a.

Table 21.8a Suggested Interview Questions Prior to Urinary Catheterization

| Interview Questions | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Do you have any history of urinary problems such as frequent urinary tract infections, urinary tract surgeries, or bladder cancer?

For males: Do you have any history of prostate enlargement or prostate problems? For females: Have you had any gynecological surgeries? |

Previous medical conditions and surgeries may interfere with urinary catheter placement. Information about a male patient’s prostate will assist in determining the size and type of catheter used. (Recall that using a catheter with a coude tip is helpful when a male patient has an enlarged prostate.) If a patient has a history of previous urinary tract infections, they may be at higher risk of developing CAUTI. |

| Have you ever had a urinary catheter placed in the past? If so, were there any problems with placement or did you experience any problems while the catheter was in place? | Questioning the patient about placement and prior catheterizations assists the nurse in identifying any problems with catheterization or if the patient has had the procedure before, they may know what to expect. |

| Do you have any questions about this procedure? How do you feel about undergoing catheterization? | The nurse should encourage patient involvement with their care and identify any fears or anxiety. Nurses can decrease or eliminate these fears and anxieties with additional information or reassurance. |

| Do you take any medications that increase urination such as diuretics or any medications that decrease urgency or frequency? If so, please describe. | Identifying medications that increase or decrease urine output is important to consider when monitoring urine output after the catheter is in place. |

| Have you had any orthopedic surgeries that may affect your ability to bend your knees or hips? Are you able to tolerate lying flat for a short period of time? | The patient may not be able to tolerate the positioning required for catheter insertion. If so, additional assistance from other staff may be required for patient comfort and safety. |

Cultural Considerations

When inserting urinary catheters, be aware of and respect cultural beliefs related to privacy, family involvement, and the request for a same-gender nurse. Inserting a urinary catheter requires visualization and manipulation of anatomical areas that are considered private by most patients. These procedures can cause emotional distress, especially if the patient has experienced any history of abuse or trauma.

Objective Assessment

In addition to performing a subjective assessment, there are several objective assessments to complete prior to insertion. See Table 21.8b for a list of objective assessments and their rationale.

Table 21.8b Objective Assessment

| Objective Data Collection | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Review the patient’s medical record for any documented medical conditions the patient may not have reported, such as urethral strictures, structural problems with the bladder or urethra, or frequent urinary tract infections. | Any type of obstruction or scar tissue within these areas may prevent the catheter from advancing into the bladder. |

| Analyze the patient's weight and most recent electrolyte values. | Weight is used to determine a patient's fluid status, especially if they have fluid overload. Electrolyte levels are also affected by fluid balance and the use of diuretic medications. Establish a baseline to use to evaluate outcomes after placing the urinary catheter. |

| Determine the patient's level of consciousness, ability to cooperate, developmental level, and age. | Evaluate the patient’s ability to follow directions and cooperate during the procedure and seek additional assistance during the procedure if needed. This data will impact how to explain the procedure to the patient. |

| Perform physical assessment of the bladder and perineum. Palpate the bladder for signs of fullness and discomfort. (Bladder emptying may also be assessed using a bladder scanner per agency policy). Inspect the perineum for erythema, discharge, drainage, skin ulcerations, or odor. Note the position of anatomical landmarks. For example, in females identify the urethra versus the vaginal opening. | A full bladder produces discomfort and urgency to void, especially on palpation. These symptoms should be relieved with the placement of a urinary catheter.

Identify any abnormal physical signs in the perineal area that may interfere with comfort during insertion. Determining the urethral opening improves accuracy and ease of insertion. |

| When examining the perineal area, note the approximate diameter of the urinary meatus. Choose the smallest, appropriately sized diameter catheter. | An appropriately sized catheter is important to avoid unnecessary discomfort or trauma to the urinary tissue. Catheters that are 14 French diameter are typically used in adults. |

Life Span Considerations

Children

It is often helpful to explain the catheterization procedure using a doll or toy. According to agency policy, a parent, caregiver, or other adult should be present in the room during the procedure. Asking a younger child to blow into a straw can help relax the pelvic muscles during catheterization.

Older Adults

The urethral meatus of older women may be difficult to identify due to atrophy of the urogenital tissue. The risk of developing a urinary tract infection may also be increased due to chronic disease and incontinence.

Expected Outcomes/Planning

Expected patient outcomes following urinary catheterization should be planned and then evaluated and documented after the procedure is completed. See Table 21.8c for sample expected outcomes related to urinary catheterization.

Table 21.8c Expected Outcomes of Urinary Catheterization

| Expected Outcomes | Rationale |

|---|---|

| The patient’s bladder is nondistended and not palpable. | Verifies appropriate bladder emptying. |

| The patient reports no abdominal or bladder discomfort or pressure. | Verifies correct catheter placement by allowing urine flow and relieving discomfort or pressure. |

| Urine output is at least 30 mL/hr. | Verifies correct catheter placement and appropriate kidney functioning. If urine output is less than 30 mL/hour, check tubing for kinking and obstruction, and notify the provider if there is no improvement after manipulating the tubing. |

| Patient verbalizes understanding of the purpose of the catheter and signs of a urinary tract infection to report. | Verifies the patient's understanding of the procedure and signs of complications. |

Implementation

When inserting an indwelling urinary catheter, the expected finding is that the catheter is inserted accurately and without discomfort, and immediate flow of clear, yellow urine into the collection bag occurs. However, unexpected events and findings can occur. See Table 21.8d for examples of unexpected findings and suggested follow-up actions.

Table 21.8d Unexpected Findings and Follow-Up Actions

| Unexpected Findings | Follow-Up Action |

|---|---|

| Urine flow does not occur when catheterizing a female patient. | The catheter may have entered the vagina and not the urethral meatus. Leave the catheter in the vagina as a landmark to avoid incorrect reinsertion. Obtain a new catheter kit and cleanse the urinary meatus again before reinsertion. If reinsertion is successful into the bladder, remove the catheter that is in vagina after the second attempt. |

| Sterile field is broken during the procedure. | If supplies or the catheter become contaminated, obtain a new catheter kit and restart the procedure. |

| Patient reports continued bladder pain or discomfort although urinary flow indicates correct catheter placement. | Ensure there is no tension pulling at the catheter. It may be helpful to deflate the balloon and advance the catheter another 2-3 inches to ensure it is in the bladder and not the urethra. If these actions do not resolve the discomfort, notify the provider because it is possible the patient is experiencing bladder spasms. Continue to monitor urine output for clarity, color, and amount and for signs of urinary tract infection. |

| The nurse is unable to advance the catheter on a male patient with an enlarged prostate. | Do not force advancement because this may cause further damage. Ask the patient to take deep breaths and try again. If a second attempt is unsuccessful, obtain a coude catheter and attempt to reinsert. If unsuccessful with a coude catheter, notify the provider. |

| Urine is cloudy, concentrated, malodorous, dark amber in color, or contains sediment, blood, or pus. | Notify the health care provider of signs and symptoms of a possible urinary tract infection. Obtain a urine specimen as prescribed. |

Evaluation

Evaluate the success of the expected outcomes established prior to the procedure.

Sample Documentation for Expected Findings

A size 14F Foley catheter inserted per provider prescription. Indication: Prolonged urinary retention. Procedure and purpose of Foley catheter explained to patient. Patient denies allergies to iodine, orthopedic limitations, or previous genitourinary surgeries. Balloon inflated with 10 mL of sterile water. Patient verbalized no discomfort or pain with balloon inflation or during the procedure. Peri-care provided before and after procedure. Catheter tubing secured to right upper thigh with stat lock. Drainage bag attached, tubing coiled loosely with no kinks, bag is below bladder level on bed frame. Urine drained with procedure 375 mL. Urine is clear, amber in color, no sediment. Patient resting comfortably; instructed the patient to notify the nurse if develops any bladder pain, discomfort, or spasms. Patient verbalized understanding.

Sample Documentation for Unexpected Findings

A size 14F Foley catheter inserted per provider prescription. Indication is for oliguria with accurate output measurements required. Procedure and purpose of Foley catheter explained to patient. Patient denies allergies to iodine, orthopedic limitations, or previous genitourinary surgeries. As the balloon was being inflated with sterile water, patient began to report discomfort. Water removed, catheter advanced one inch and balloon reinflated with 10 mL of sterile water. Patient denied discomfort after the catheter advancement. Catheter tubing secured to right upper thigh with stat lock. Drainage bag attached, tubing coiled loosely with no kinks, bag is below bladder level. Urine drained with procedure 100 mL. Urine is dark amber, noticeable sediment in tubing, with foul odor. Patient resting comfortably, denies any bladder pain or discomfort. Instructed the patient to notify the nurse if develops any bladder pain, discomfort, or urinary spasms. Patient verbalized understanding. Notify the health care provider of urine assessment. Continue monitoring patient for any new or worsening symptoms such as change in mental status, fever, chills, or hematuria.

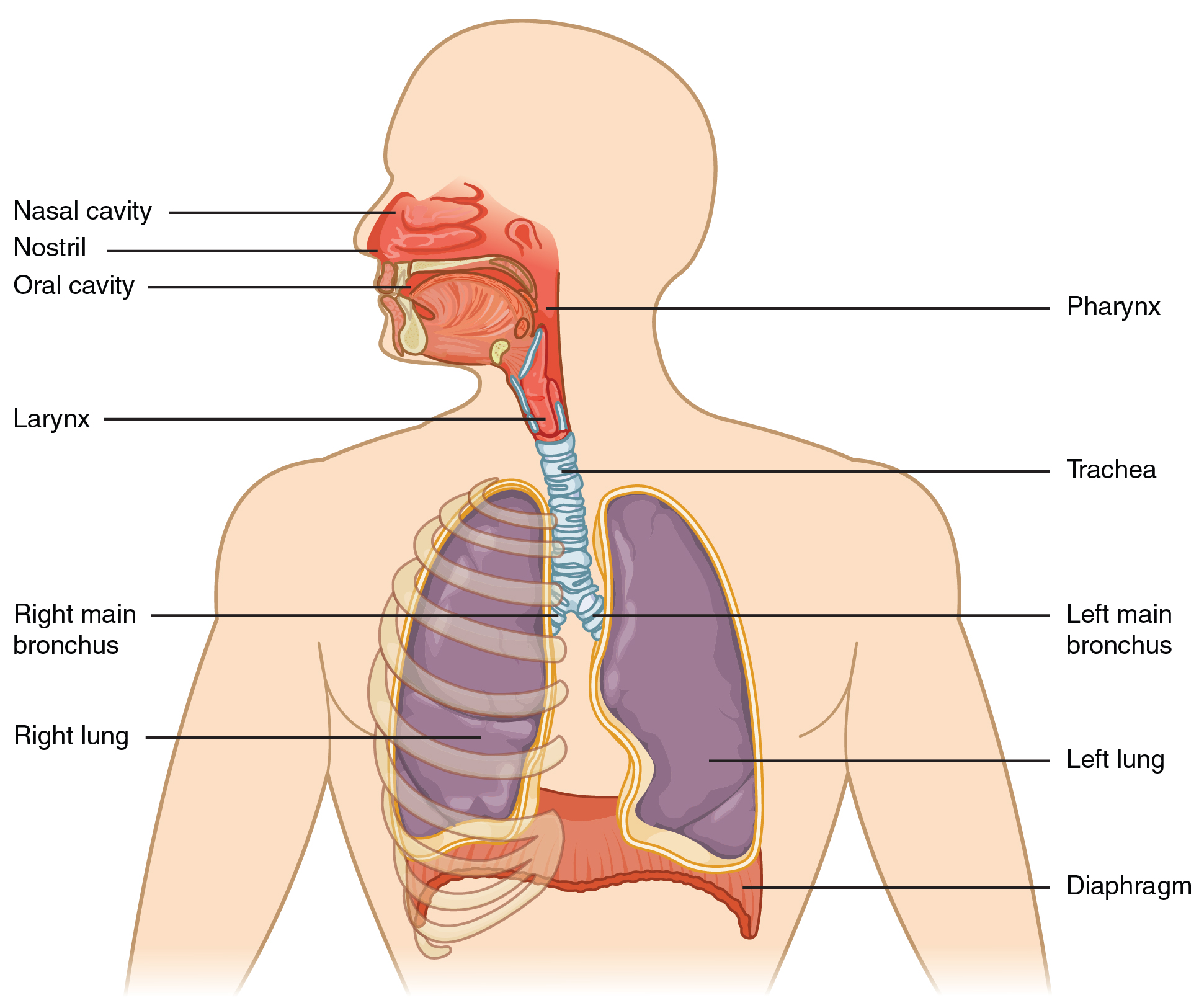

Respiratory System Anatomy

It is important for the nurse to have an understanding of the underlying structures of the respiratory system before performing suctioning to ensure that care is given to protect sensitive tissues and that airways are appropriately assessed during the suctioning procedure. See Figure 22.1[39] for an illustration of the anatomy of the respiratory system.

Maintaining a patent airway is a top priority and one of the “ABCs” of patient care (i.e., Airway, Breathing, and Circulation). Suctioning is often required in acute care settings for patients who cannot maintain their own airway due to a variety of medical conditions such as respiratory failure, stroke, unconsciousness, or postoperative care. The suctioning procedure is useful for removing mucus that may obstruct the airway and compromise the patient’s breathing ability.

To read more details about the respiratory system, see the “Respiratory Assessment” chapter.

Respiratory Failure and Respiratory Arrest

Respiratory failure and respiratory arrest often require emergency suctioning. Respiratory failure is a life-threatening condition that is caused when the respiratory system cannot get enough oxygen from the lungs into the blood to oxygenate the tissues, or there are high levels of carbon dioxide in the blood that the body cannot effectively eliminate via the lungs. Acute respiratory failure can happen quickly without much warning. It is often caused by a disease or injury that affects breathing, such as pneumonia, opioid overdose, stroke, or a lung or spinal cord injury. Acute respiratory failure requires emergency treatment. Untreated respiratory failure can lead to respiratory arrest.

Signs and symptoms of respiratory failure include shortness of breath (dyspnea), rapid breathing (tachypnea), rapid heart rate (tachycardia), unusual sweating (diaphoresis), decreasing pulse oximetry readings below 90%, and air hunger (a feeling as if you can't breathe in enough air). In severe cases, signs and symptoms may include cyanosis (a bluish color of the skin, lips, and fingernails), confusion, and sleepiness.

The main goal of treating respiratory failure is to ensure that sufficient oxygen reaches the lungs and is transported to the other organs while carbon dioxide is cleared from the body.[40] Treatment measures may include suctioning to clear the airway while also providing supplemental oxygen using various oxygenation devices. Severe respiratory distress may require intubation and mechanical ventilation, or the emergency placement of a tracheostomy may be performed if the airway is obstructed. For additional details about oxygenation and various oxygenation devices, go to the “Oxygen Therapy" chapter.

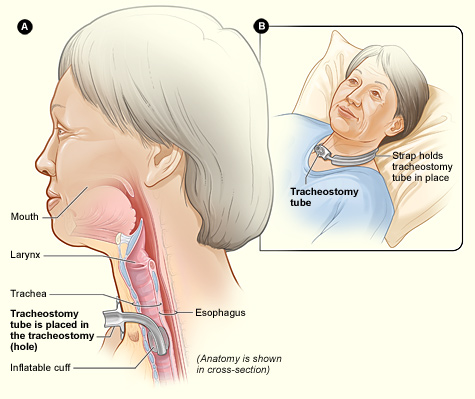

Tracheostomy

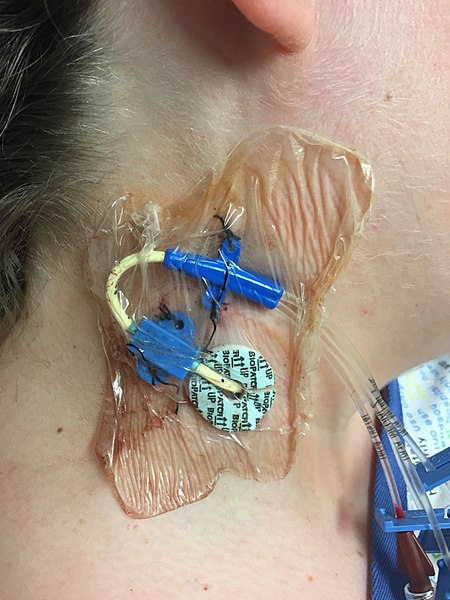

A tracheostomy is a surgically created opening called a stoma that goes from the front of the patient’s neck into the trachea. A tracheostomy tube is placed through the stoma and directly into the trachea to maintain an open (patent) airway. See Figure 22.2[41] for an illustration of a patient with a tracheostomy tube in place.

Placement of a tracheostomy tube may be performed emergently or as a planned procedure due to the following:

- A large object blocking the airway

- Respiratory failure or arrest

- Severe neck or mouth injuries

- A swollen or blocked airway due to inhalation of harmful material such as smoke, steam, or other toxic gases

- Cancer of the throat or neck, which can affect breathing by pressing on the airway

- Paralysis of the muscles that affect swallowing

- Surgery around the larynx that prevents normal breathing and swallowing

- Long-term oxygen therapy via a mechanical ventilator[42]

See Figure 22.3[43] for an image of the parts of a tracheostomy tube. The outside end of the outer cannula has a flange that is placed against the patient’s neck. The flange is secured around the patient’s neck with tie straps, and a split 4" x 4" tracheostomy dressing is placed under the flange to absorb secretions. A cuff is typically present on the distal end of the outer cannula to make a tight seal in the airway. (See the top image in Figure 22.3.) The cuff is inflated and deflated with a syringe attached to the pilot balloon. Most tracheostomy tubes have a hollow inner cannula inside the outer cannula that is either disposable or removed for cleaning as part of the tracheostomy care procedure. (See the middle image of Figure 22.3.) A solid obturator is used during the initial tracheostomy insertion procedure to help guide the outer cannula through the tracheostomy and into the airway. (See the bottom image of Figure 22.3.) It is removed after insertion and the inner cannula is slid into place.

When a tracheostomy is placed, the provider determines if a fenestrated or unfenestrated outer cannula is needed based on the patient's condition. A fenestrated tube is used for patients who can speak with their tracheostomy tube in place. Under the guidance of a speech pathologist and respiratory therapist, the inner cannula is eventually removed from a fenestrated tube and the cuff deflated so the patient is able to speak. Otherwise, a patient with a tracheostomy tube is unable to speak because there is no airflow over the vocal cords, and alternative communication measures, such as a whiteboard, pen and paper, or computer device with note-taking ability, must be put into place by the nurse. Suctioning should never be performed through a fenestrated tube without first inserting a nonfenestrated inner cannula, or severe tracheal damage can occur. See Figure 22.4[44] for images of a fenestrated and nonfenestrated outer cannula.

Caring for a patient with a tracheostomy tube includes providing routine tracheostomy care and suctioning. Tracheostomy care is a procedure performed routinely to keep the flange, tracheostomy dressing, ties or straps, and surrounding area clean to reduce the introduction of bacteria into the trachea and lungs. The inner cannula becomes occluded with secretions and must be cleaned or replaced frequently according to agency policy to maintain an open airway. Suctioning through the tracheostomy tube is also performed to remove mucus and to maintain a patent airway.

Suctioning via the oropharyngeal (mouth) and nasopharyngeal (nasal) routes is performed to remove accumulated saliva, pulmonary secretions, blood, vomitus, and other foreign material from these areas that cannot be removed by the patient’s spontaneous cough or other less invasive procedures. Nasal and pharyngeal suctioning are performed in a wide variety of settings, including critical care units, emergency departments, inpatient acute care, skilled nursing facility care, home care, and outpatient/ambulatory care. Suctioning is indicated when the patient is unable to clear secretions and/or when there is audible or visible evidence of secretions in the large/central airways that persist in spite of the patient's best cough effort. Need for suctioning is evidenced by one or more of the following:

- Visible secretions in the airway

- Chest auscultation of coarse, gurgling breath sounds, rhonchi, or diminished breath sounds

- Reported feeling of secretions in the chest

- Suspected aspiration of gastric or upper airway secretions

- Clinically apparent increased work of breathing

- Restlessness

- Unrelieved coughing[45]

In emergent situations, a provider order is not necessary for suctioning to maintain a patient’s airway. However, routine suctioning does require a provider order.

For oropharyngeal suctioning, a device called a Yankauer suction tip is typically used for suctioning mouth secretions. A Yankauer device is rigid and has several holes for suctioning secretions that are commonly thick and difficult for the patient to clear. See Figure 22.5[46] for an image of a Yankauer device. In many agencies, Yankauer suctioning can be delegated to trained assistive personnel if the patient is stable, but the nurse is responsible for assessing and documenting the patient’s respiratory status.

Nasopharyngeal suctioning removes secretions from the nasal cavity, pharynx, and throat by inserting a flexible, soft suction catheter through the nares. This type of suctioning is performed when oral suctioning with a Yankauer is ineffective. See Figure 22.6[47] for an image of a sterile suction catheter.

![“DSC_0210-150x150.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT) is licensed under CC BY 4.0. [/footnote] Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/5-7-oral-suctioning/ Photo of a sterile suction catheter being handled by a person wearing gloves](https://opencontent.ccbcmd.edu/app/uploads/sites/30/2024/08/DSC_0210-scaled-1.jpg)

Extension tubing is used to attach the Yankauer or suction catheter device to a suction canister that is attached to wall suction or a portable suction source. The amount of suction is set to an appropriate pressure according to the patient’s age. See Figure 22.7[48] for an image of extension tubing attached to a suction canister that is connected to a wall suctioning source.

![“DSC_0206-e1437445438554.jpg” by by British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT) is licensed under CC BY 4.0. [/footnote]. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/5-7-oral-suctioning/ Photo showing tubing attaching suction canister to wall suction source](https://opencontent.ccbcmd.edu/app/uploads/sites/30/2024/08/DSC_0206-e1437445438554-scaled-1.jpg)

Follow agency policy regarding setting suction pressure. Pressure should not exceed 150 mm Hg because higher pressures have been shown to cause trauma, hypoxemia, and atelectasis. The following ranges are appropriate pressure according to the patient's age:

- Neonates: 60-80 mm Hg

- Infants: 80-100 mm Hg

- Children: 100-120 mm Hg

- Adults: 100-150 mm Hg

Checklist for Oropharyngeal or Nasopharyngeal Suctioning

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Oropharyngeal or Nasopharyngeal Suctioning.”

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: Yankauer or suction catheter, suction machine or wall suction device, suction canister, connecting tubing, pulse oximeter, stethoscope, PPE (e.g., mask, goggles or face shield, nonsterile gloves), sterile gloves for suctioning with sterile suction catheter, towel or disposable paper drape, nonsterile basin or disposable cup, water soluble lubricant, normal saline or tap water.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Adjust the bed to a comfortable working height and lower the side rail closest to you.

- Position the patient:

- If conscious, place the patient in a semi-Fowler’s position.

- If unconscious, place the patient in the lateral position, facing you.

- Move the bedside table close to your work area and raise it to waist height.

- Place a towel or waterproof pad across the patient’s chest.

- Adjust the suction to the appropriate pressure:

- Adults and adolescents: no more than 150 mm Hg

- Children: no more than 120 mmHg

- Infants: no more than 100 mm Hg

- Neonates: no more than 80 mm Hg

For a portable unit:

- Adults: 10 to 15 cm Hg

- Adolescents: 8 to 15 cm Hg

- Children: 8 to 10 cm Hg

- Infants: 8 to 10 cm Hg

- Neonates: 6 to 8 cm Hg

- Put on a clean glove and occlude the end of the connection tubing to check suction pressure.

- Place the connecting tubing in a convenient location (e.g., at the head of the bed).

- Open the sterile suction package using aseptic technique. (NOTE: The open wrapper or container becomes a sterile field to hold other supplies.) Carefully remove the sterile container, touching only the outside surface. Set it up on the work surface and fill with sterile saline using sterile technique.

- Place a small amount of water-soluble lubricant on the sterile field, taking care to avoid touching the sterile field with the lubricant package.

- Increase the patient’s supplemental oxygen level or apply supplemental oxygen per facility policy or primary care provider order.

- Don additional PPE. Put on a face shield or goggles and mask.

- Don sterile gloves. The dominant hand will manipulate the catheter and must remain sterile.

- The nondominant hand is considered clean rather than sterile and will control the suction valve on the catheter.

- In the home setting and other community-based settings, maintenance of sterility is not necessary.

- With the dominant gloved hand, pick up the sterile suction catheter. Pick up the connecting tubing with the nondominant hand and connect the tubing and suction catheter.

- Moisten the catheter by dipping it into the container of sterile saline. Occlude the suction valve on the catheter to check for suction.

- Encourage the patient to take several deep breaths.

- Apply lubricant to the first 2 to 3 inches of the catheter, using the lubricant that was placed on the sterile field.

- Remove the oxygen delivery device, if appropriate. Do not apply suction as the catheter is inserted. Hold the catheter between your thumb and forefinger.

- Insert the catheter. For nasopharyngeal suctioning, gently insert the catheter through the naris and along the floor of the nostril toward the trachea. Roll the catheter between your fingers to help advance it. Advance the catheter approximately 5 to 6 inches to reach the pharynx. For oropharyngeal suctioning, insert the catheter through the mouth, along the side of the mouth toward the trachea. Advance the catheter 3 to 4 inches to reach the pharynx.

- Apply suction by intermittently occluding the suction valve on the catheter with the thumb of your nondominant hand and continuously rotate the catheter as it is being withdrawn.[50]

- Suction only on withdrawal and do not suction for more than 10 to 15 seconds at a time to minimize tissue trauma.

- Replace the oxygen delivery device using your nondominant hand, if appropriate, and have the patient take several deep breaths.

- Flush the catheter with saline. Assess the effectiveness of suctioning by listening to lung sounds and repeat, as needed, and according to the patient’s tolerance. Wrap the suction catheter around your dominant hand between attempts:

- Repeat the procedure up to three times until gurgling or bubbling sounds stop, and respirations are quiet. Allow 30 seconds to 1 minute between passes to allow reoxygenation and reventilation.[51]

- When suctioning is completed, remove gloves from the dominant hand over the coiled catheter, pulling them off inside out.

- Remove the glove from the nondominant hand and dispose of gloves, catheter, and the container with solution in the appropriate receptacle.

- Turn off the suction. Remove the supplemental oxygen placed for suctioning, if appropriate.

- Remove face shield or goggles and mask; perform hand hygiene.

- Perform oral hygiene on the patient after suctioning.

- Reassess the patient’s respiratory status, including respiratory rate, effort, oxygen saturation, and lung sounds.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the procedure and related assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

Sample Documentation

Sample Documentation of Expected Findings

Patient complaining of difficulty coughing up secretions. Order obtained for nasopharyngeal suctioning. Procedure explained to patient. Vitals signs prior to procedure: heart rate 88 regular, respiratory rate 28/minute, O2 saturation 88% on room air. Coarse rhonchi present over anterior upper airway. No cyanosis. Patient suctioned through left nare x 1 at 120 mm Hg with small amount clear, white, thick sputum obtained. Post-procedure vital signs: heart rate 78 regular, respiratory rate 18/minute, O2 saturation 94% room air. Lung sounds clear to auscultation and no cyanosis present.

Sample Documentation of Unexpected Findings

Patient complaining of difficulty expectorating secretions. Order obtained for nasopharyngeal suctioning and procedure explained to patient. Vital signs prior to procedure: heart rate 88 and regular, respiratory rate 28/minute, and O2 sat 88% room air. Coarse rhonchi present over anterior upper airway. No cyanosis. After first suctioning pass, patient coughing uncontrollably. Procedure stopped and emergency assistance requested from respiratory therapist. Post-procedure vital signs: heart rate 78 and regular, respiratory rate 18/minute, and O2 sat 94% room air. Course rhonchi remain over anterior upper airway but no cyanosis present. Dr. Smith notified and STAT order for chest X-ray received. Dr. Smith to be called with results.

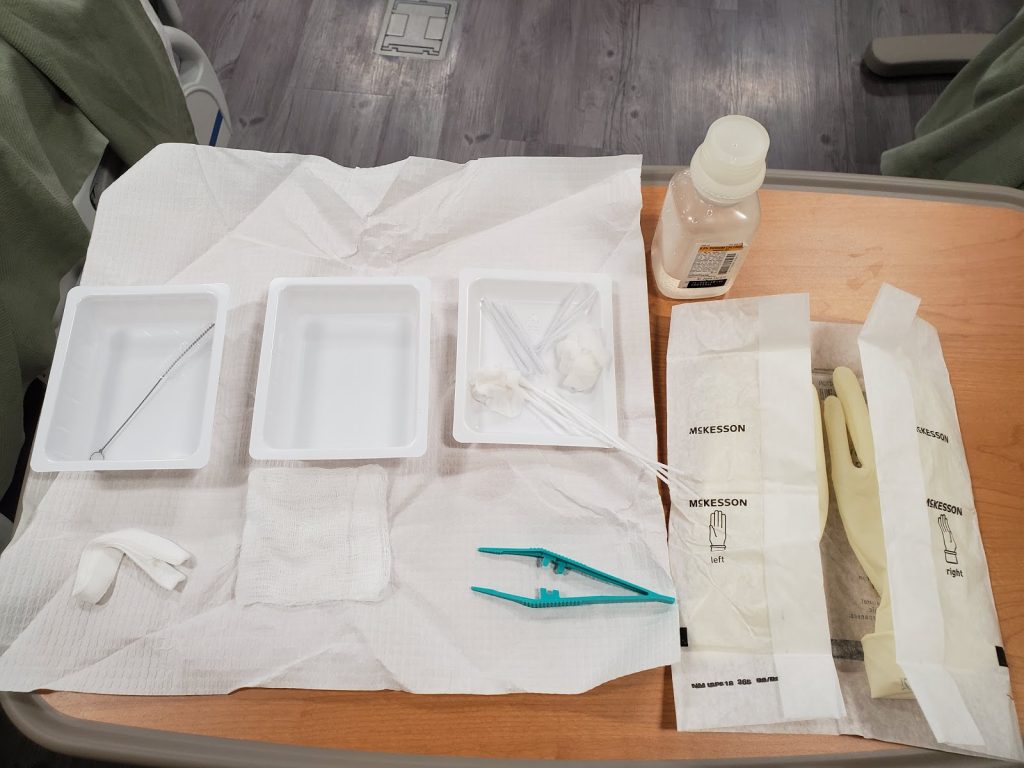

Tracheostomy care is provided on a routine basis to keep the tracheostomy tube’s flange, inner cannula, and surrounding area clean and dry and to reduce the amount of bacteria entering the artificial airway, lungs, and maintain skin integrity. See Figure 22.9[52] for an image of a sterile tracheostomy care kit.

Replacing and Cleaning an Inner Cannula

The primary purpose of the inner cannula is to prevent tracheostomy tube obstruction. Many sources of obstruction can be prevented if the inner cannula is regularly cleaned and replaced. Some inner cannulas are designed to be disposable, while others are reusable for a number of days. Follow agency policy for inner cannula replacement or cleaning, but as a rule of thumb, inner cannula cleaning should be performed every 12-24 hours at a minimum. Cleaning may be needed more frequently depending on the type of equipment, the amount and thickness of secretions, and the patient’s ability to cough up the secretions.

Changing the inner cannula may encourage the patient to cough and bring mucus out of the tracheostomy. For this reason, the inner cannula should be replaced prior to changing the tracheostomy dressing to prevent secretions from soiling the new dressing. If the inner cannula is disposable, no cleaning is required.[53]

Checklist for Tracheostomy Care With a Reusable Inner Cannula

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Tracheostomy Care.”

Stoma site should be assessed and a clean dressing applied at least once per shift. Wet or soiled dressings should be changed immediately.[54] Follow agency policy regarding cleaning the inner cannula; it should be inspected at least twice daily and cleaned as needed.

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: bedside table, towel, sterile gloves, pulse oximeter, PPE (i.e., mask, goggles, gown, or face shield), tracheostomy suctioning equipment, bag valve mask (should be located in the room), and a sterile tracheostomy care kit (or sterile cotton-tipped applicators, sterile manufactured tracheostomy split sponge dressing, sterile basin, normal saline, and a disposable inner cannula or a small, sterile brush to clean the reusable inner cannula).

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Raise the bed to waist level and place the patient in a semi-Fowler’s position.

- Verify that there is a backup tracheostomy kit available.

- Don appropriate PPE.

- Perform tracheal suctioning if indicated.

- Remove and discard the tracheostomy dressing. Inspect drainage on the dressing for color and amount and note any odor.

- Inspect stoma site for redness, drainage, and signs and symptoms of infection.

- Remove the gloves and perform proper hand hygiene.

- Open the sterile package and loosen the bottle cap of sterile saline.

- Don one sterile glove on the dominant hand.

- Open the sterile drape and place it on the patient’s chest.

- Set up the equipment on the sterile field.

- Remove the cap and pour saline in both basins with the ungloved hand (4"-6” above basin).

- Don the second sterile glove.

- Prepare and arrange supplies. Place pipe cleaners, trach ties, trach dressing, and forceps on the field. Moisten cotton applicators and place them in the third (empty) basin. Moisten two 4" x 4" pads in saline, wring out, open, and separately place each one in the third basin. Leave one 4" x 4" dry.

- With nondominant “contaminated” hand, remove the trach collar (if applicable) and remove (unlock and twist) the inner cannula. If the patient requires continuous supplemental oxygen, place the oxygenation device near the outer cannula or ask a staff member to assist in maintaining the oxygen supply to the patient.

- Place the inner cannula in the saline basin.

- Pick up the inner cannula with your nondominant hand, holding it only by the end usually exposed to air.

- With your dominant hand, use a brush to clean the inner cannula. Place the brush back into the saline basin.

- After cleaning, place the inner cannula in the second saline basin with your nondominant hand and agitate for approximately 10 seconds to rinse off debris. Repeat cleansing with brush as needed.

- Dry the inner cannula with the pipe cleaners and place the inner cannula back into the outer cannula. Lock it into place and pull gently to ensure it is locked appropriately. Reattach the preexisting oxygenation device.

- Clean the stoma with cotton applicators using one on the superior aspect and one on the inferior aspect.

- With your dominant, noncontaminated hand, moisten sterile gauze with sterile saline and wring out excess. Assess the stoma for infection and skin breakdown caused by flange pressure. Clean the stoma with the moistened gauze starting at the 12 o’clock position of the stoma and wipe toward the 3 o’clock position. Begin again with a new gauze square at 12 o’clock and clean toward 9 o’clock. To clean the lower half of the site, start at the 3 o’clock position and clean toward 6 o’clock; then wipe from 9 o’clock to 6 o’clock, using a clean moistened gauze square for each wipe. Continue this pattern on the surrounding skin and tube flange. Avoid using a hydrogen peroxide mixture because it can impair healing.[55]

- Use sterile gauze to dry the area.

- Apply the sterile tracheostomy split sponge dressing by only touching the outer edges.

- Replace trach ties as needed. (The literature overwhelmingly recommends a two-person technique when changing the securing device to prevent tube dislodgement. In the two-person technique, one person holds the trach tube in place while the other changes the securing device). Thread the clean tie through the opening on one side of the trach tube. Bring the tie around the back of the neck, keeping one end longer than the other. Secure the tie on the opposite side of the trach. Make sure that only one finger can be inserted under the tie.

- Remove the old tracheostomy ties.

- Remove gloves and perform proper hand hygiene.

- Provide oral care. Oral care keeps the mouth and teeth not only clean, but also has been shown to prevent hospital-acquired pneumonia.

- Lower the bed to the lowest position. If the patient is on a mechanical ventilator, the head of the bed should be maintained at 30-45 degrees to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the procedure and related assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

Sample Documentation

Sample Documentation of Expected Findings

Tracheostomy care provided with sterile technique. Stoma site free of redness or drainage. Inner cannula cleaned and stoma dressing changed. Patient tolerated the procedure without difficulties.

Sample Documentation of Unexpected Findings

Tracheostomy care provided with sterile technique. Stoma site is erythematous, warm, and tender to palpation. Inner cannula cleaned and stoma dressing changed. Patient tolerated the procedure without difficulties. Dr. Smith notified of change in condition of stoma at 1315 and stated would assess the patient this afternoon.

View the following YouTube videos from Santa Fe College for more information on tracheostomy care and suctioning:

Learning Activities

(Answers to “Learning Activities” can be found in the “Answer Key” at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. You are caring for a patient with a tracheostomy. What supplies should you ensure are in the patient's room when you first assess the patient?

2. Your patient with a tracheostomy puts on their call light. As you enter the room, the patient is coughing violently and turning red. Prioritize the action steps that you will take.

- Assess lung sounds

- Suction patient

- Provide oxygen via the trach collar if warranted

- Check pulse oximetry

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 22, Assignment 1.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 22, Assignment 2.

Learning Activities

(Answers to “Learning Activities” can be found in the “Answer Key” at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. You are caring for a patient with a tracheostomy. What supplies should you ensure are in the patient's room when you first assess the patient?

2. Your patient with a tracheostomy puts on their call light. As you enter the room, the patient is coughing violently and turning red. Prioritize the action steps that you will take.

- Assess lung sounds

- Suction patient

- Provide oxygen via the trach collar if warranted

- Check pulse oximetry

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 22, Assignment 1.

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 22, Assignment 2.

Fenestrated cannula: Type of tracheostomy tube that contains holes so the patient can speak if the cuff is deflated and the inner cannula is removed.

Flange: The end of the tracheostomy tube that is placed securely against the patient’s neck.

Inner cannula: The cannula inside the outer cannula that is removed during tracheostomy care by the nurse. Inner cannulas can be disposable or reusable with appropriate cleaning.

Oropharyngeal suctioning: Suction of secretions through the mouth, often using a Yankauer device.

Outer cannula: The outer cannula placed by the provider through the tracheostomy stoma and continuously remains in place.

Suction canister: A container for collecting suctioned secretions that is attached to a suction source.

Suction catheter: A soft, flexible, sterile catheter used for nasopharyngeal and tracheostomy suctioning.

Tracheostomy: A surgically created opening that goes from the front of the neck into the trachea.

Tracheostomy dressing: A manufactured dressing used with tracheostomies that does not shed fibers, which could potentially be inhaled by the patient.

Yankauer suction tip: Rigid device used to suction secretions from the mouth.

Nurses access patients' veins to collect blood (i.e., perform phlebotomy) and to administer intravenous (IV) therapy. This section will describe several methods for collecting blood, as well as review the basic concepts of IV therapy.

Blood Collection

Nurses collect blood samples from patients using several methods, including venipuncture, capillary blood sampling, and blood draws from venous access devices. Blood may also be drawn from arteries by specially trained professionals for certain laboratory testing.

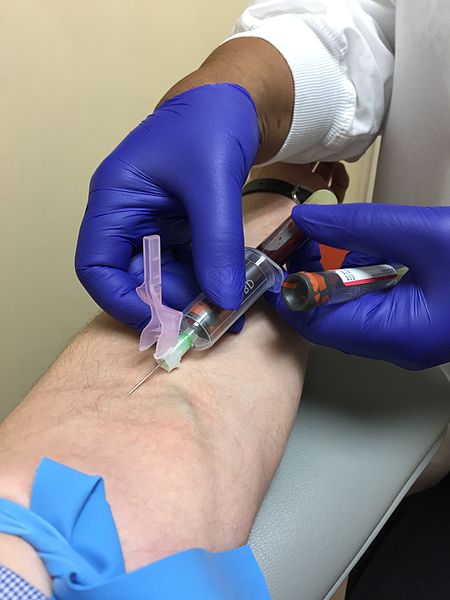

Venipuncture

Venipuncture involves the process of introducing a needle into a patient’s vein to collect a blood sample or insert an IV catheter. See Figure 23.1[58] for an image of venipuncture. Blood sampling with venipuncture may be initiated by nurses, phlebotomists, or other trained personnel. Venipuncture for collection of a blood sample is an important part of data collection to assess a patient’s health status. It is commonly performed to examine hematologic and immune issues such as the body’s oxygen-carrying capacity, infection, and clotting function. It is also useful for assessing metabolic and nutrition issues such as electrolyte status and kidney functioning.

Blood collection is commonly performed via venipuncture from veins in the arms or hands. The most common sites for venipuncture are the large veins located on the antecubital fossa (i.e., the inner side of the elbow). These veins are often preferred for venipuncture because their larger size increases their ability to withstand repetitive blood sampling. However, these veins are not preferred for intravenous therapy due to the mechanical obstruction that can occur in the IV catheter when the elbow joint is contracted.

To perform the skill of venipuncture, the nurse performs many similar steps that occur with IV cannulation. The process of venipuncture for blood sample collection is outlined in the Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills "Perform Venipuncture Blood Draw" checklist.

Blood Samples From Central Venous Access Devices

Blood may also be collected by nurses from a patient's existing central venous access device (CVAD). A CVAD is a type of vascular access that involves the insertion of a catheter into a large vein in the arm, neck, chest, or groin.[59]

CVADs are discussed in more detail in the Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills "Manage Central Lines" chapter that also contains the "Obtain a Blood Sample From a CVAD" checklist.

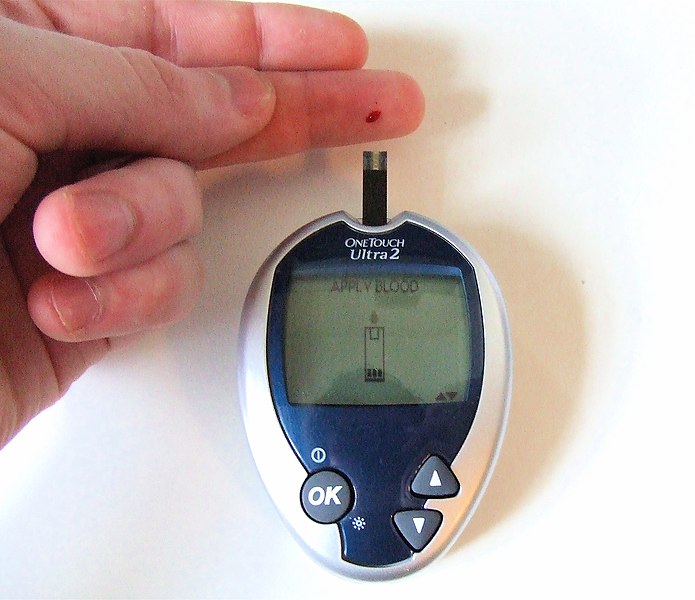

Capillary Blood Sampling

Nurses also collect small amounts of blood for testing via capillary blood sampling. Capillary blood testing occurs when blood is collected from capillaries located near the surface of the skin. Capillaries in the fingers are used for testing in adults whereas capillaries in the heels are used for infants. An example of capillary blood testing is bedside glucose testing. See Figure 23.2[60] for an image of capillary blood glucose testing.

Capillary blood testing is typically used when repetitive sampling is needed. However, not all blood tests can be performed on capillary blood, and some clinical conditions make capillary blood testing inappropriate, such as when a patient is hypotensive with limited venous return.

Review how to perform capillary blood glucose testing in the "Blood Glucose Monitoring" section of the "Specimen Collection" chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills.

Arterial Blood Sampling