6.11 Other Disorders of Head and Neck

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is the medical diagnosis for inflamed sinuses that can be caused by a viral or bacterial infection. When the nasal membranes become swollen, the drainage of mucous is blocked and causes pain.

There are several types of sinusitis, including these types:

- Acute Sinusitis: Infection lasting up to 4 weeks

- Chronic Sinusitis: Infection lasting more than 12 weeks

- Recurrent Sinusitis: Several episodes of sinusitis within a year

Symptoms of sinusitis can include fever, weakness, fatigue, cough, and congestion. There may also be mucus drainage in the back of the throat, called postnasal drip. Health care providers diagnose sinusitis based on symptoms and an examination of the nose and face. Treatments include antibiotics, decongestants, and pain relievers.[1]

Pharyngitis

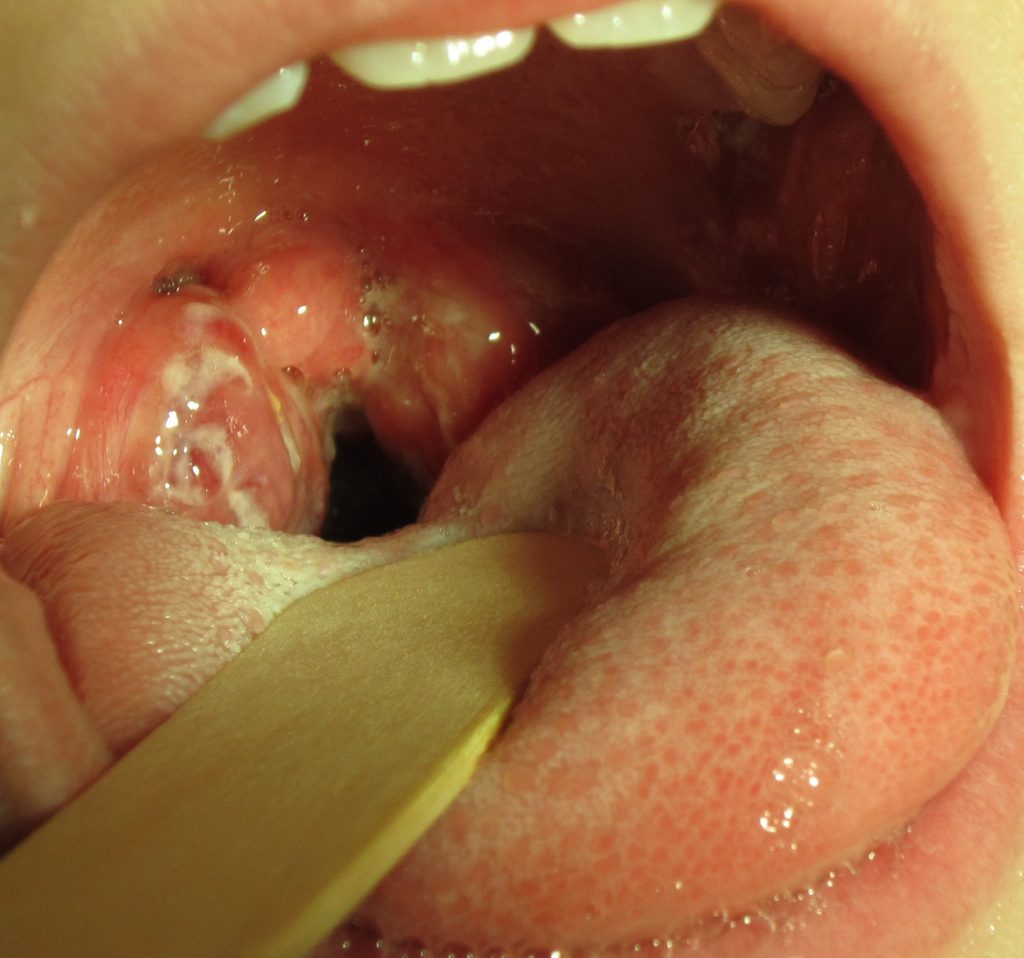

Pharyngitis is the medical term used for infection and/or inflammation in the back of the throat (pharynx). Common causes of pharyngitis are the cold viruses, influenza, strep throat caused by group A streptococcus, and mononucleosis. Strep throat typically causes white patches on the tonsils with a fever and enlarged lymph nodes. It must be treated with antibiotics to prevent potential complications in the heart and kidneys. See Figure 6.27[2] for an image of strep throat in a child.

If not diagnosed as strep throat, most cases of pharyngitis are caused by viruses, and the treatment is aimed at managing the symptoms. Nurses can teach clients the following ways to decrease the discomfort of a sore throat:

- Drink soothing liquids such as lemon tea with honey or ice water.

- Gargle several times a day with warm salt water made of 1/2 tsp. of salt in 1 cup of water.

- Suck on hard candies or throat lozenges.

- Use a cool-mist vaporizer or humidifier to moisten the air.

- Try over-the-counter pain medicines, such as acetaminophen.[3]

Tonsillitis

Tonsillitis is a common condition particularly in children that involves inflammation of the tonsils, which are two oval-shaped pads of tissue at the back of the throat. It is often caused by viral or bacterial infections, with the most frequent culprits being the Streptococcus bacteria. The inflammation can lead to symptoms such as sore throat, difficulty swallowing, fever, swollen lymph nodes, and sometimes a distinctive white or yellow coating on the tonsils. In severe cases, individuals may experience difficulty breathing due to swollen tonsils obstructing the airway.

Interventions for tonsillitis typically depend on the underlying cause. Viral tonsillitis often resolves on its own with rest, hydration, and over-the-counter pain relievers to manage symptoms. Bacterial tonsillitis, particularly when caused by Streptococcus, may require antibiotic treatment to prevent complications such as rheumatic fever. In recurrent or severe cases, surgical removal of the tonsils, known as a tonsillectomy, may be recommended to alleviate symptoms and prevent future occurrences. Regular gargling with warm salt water and maintaining good oral hygiene can also help soothe symptoms and prevent infection spread.[4]

Epistaxis

Epistaxis, the medical term for a nosebleed, is a common problem affecting up to 60 million Americans each year. Although most cases of epistaxis are minor and manageable with conservative measures, severe cases can become life-threatening if the bleeding cannot be stopped.[5] See Figure 6.28[6] for an image of a severe case of epistaxis.

The most common cause of epistaxis is dry nasal membranes in winter months due to low temperatures and low humidity. Other common causes are picking inside the nose with fingers, trauma, anatomical deformity, high blood pressure, and clotting disorders. Medications associated with epistaxis are aspirin, clopidogrel, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticoagulants.[7]

To treat a nosebleed, have the victim lean forward at the waist and pinch the lateral sides of the nose with the thumb and index finger for up to 15 minutes while breathing through the mouth.[8] Continued bleeding despite this intervention requires urgent medical intervention such as nasal packing.

Media Attributions

- Strep_throat2010-1024×958

- Epistaxis1

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Aug 17]. Sinusitis; [updated 2020, Jun 10; reviewed 2016, Oct 26]; [cited 2020, Sep 4]; https://medlineplus.gov/sinusitis.html ↵

- “Strep throat2010.JPG” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, May 1). Disparities in oral health. https://www.cdc.gov/OralHealth/oral_health_disparities/ ↵

- Anderson, J., & Paterek, E. Tonsillitis. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544342/ ↵

- Fatakia, A., Winters, R., & Amedee, R. G. (2010). Epistaxis: A common problem. The Ochsner Journal, 10(3), 176–178. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096213/ ↵

- “Epstaxis1.jpg” by Welleschik is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Fatakia, A., Winters, R., & Amedee, R. G. (2010). Epistaxis: A common problem. The Ochsner Journal, 10(3), 176–178. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096213/ ↵

- American Heart Association. (2000). Part 5: New guidelines for first aid. Circulation, 102(supplement 1). https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circ.102.suppl_1.I-77 ↵

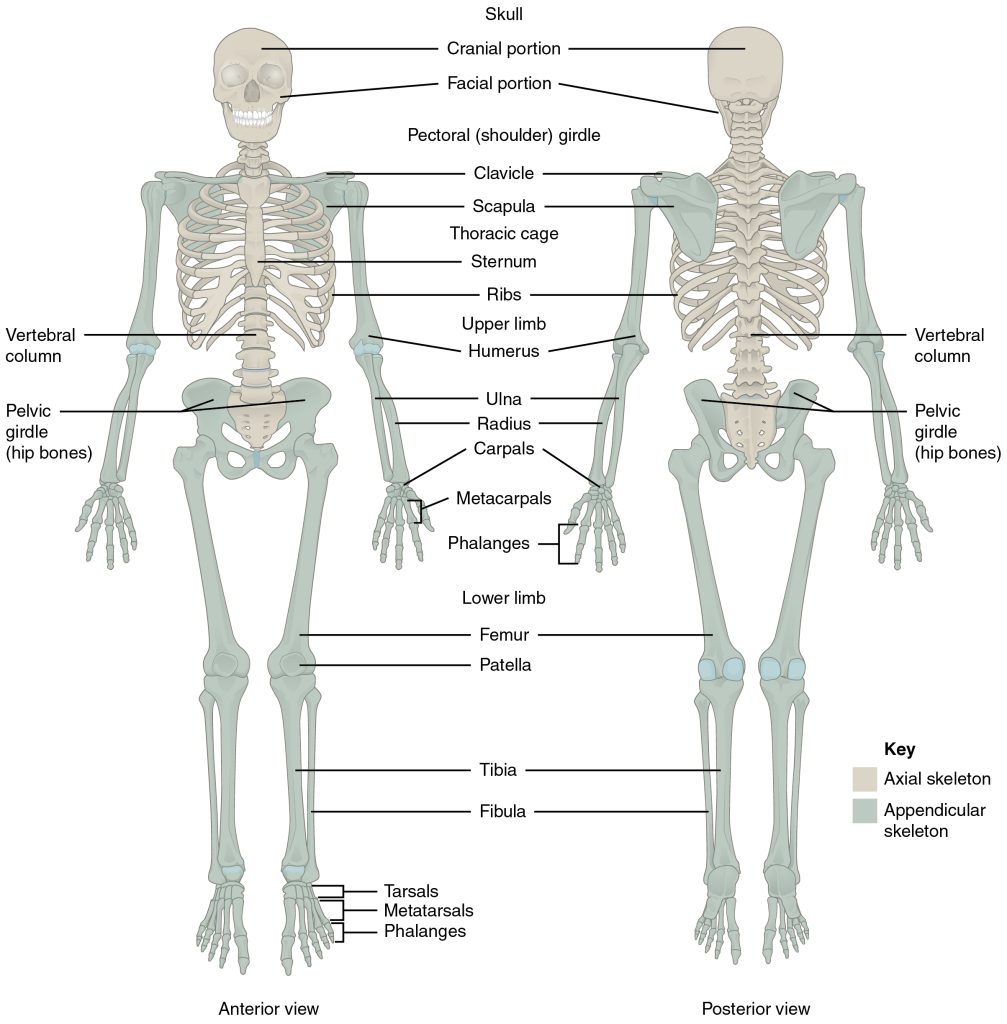

Skeleton

The skeleton is composed of 206 bones that provide the internal supporting structure of the body. See Figure 13.1[1] for an illustration of the major bones in the body. The bones of the lower limbs are adapted for weight-bearing support, stability, and walking. The upper limbs are highly mobile with large range of movements, along with the ability to easily manipulate objects with our hands and opposable thumbs.[2]

For additional information about the bones in the body, visit the OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology book.

Many different bones are connected together by ligaments. Most bones of the skill are held together by sutures, a narrow fibrous joint. Ligaments are strong bands of fibrous connective tissue that strengthen and support the joint by anchoring the bones together and preventing their separation. Ligaments allow for normal movements of a joint while also limiting the range of these motions to prevent excessive or abnormal joint movements.[3]

Muscles

There are three types of muscle tissue: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle. Skeletal muscles are attached to the skeleton and produce movement, assist in maintaining posture, protect internal organs, and generate body heat. Skeletal muscles are voluntary, meaning a person is able to consciously control them, but they also depend on signals from the nervous system to work properly. Other types of muscles are involuntary and are controlled by the autonomic nervous system, such as the smooth muscle within our bronchioles.[4] Cardiac muscles are located only in the heart and are involuntary muscles that the autonomic nervous system controls. Smooth muscle makes up the organs, blood vessels, digestive tract, skin, and other areas and is controlled by the autonomic nervous system.

See Figure 13.2[5] for an illustration of skeletal muscle.

To move the skeleton, the tension created by the contraction of the skeletal muscles is transferred to the tendons, strong bands of dense, regular connective tissue that connect muscles to bones.[6]

For additional information about skeletal muscles, visit the OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology book.

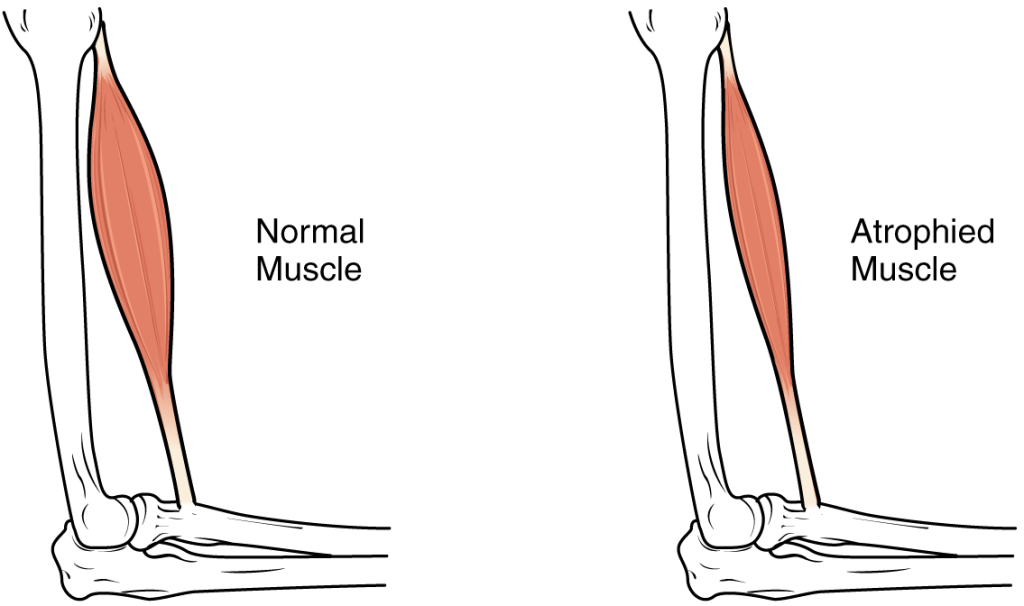

Muscle Atrophy

Muscle atrophy is the thinning or loss of muscle tissue. See Figure 13.3[7] for an image of muscle atrophy. There are three types of muscle atrophy: physiologic, pathologic, and neurogenic.

Physiologic atrophy is caused by not using the muscles and can often be reversed with exercise and improved nutrition. People who are most affected by physiologic atrophy are those who:

- Have seated jobs, health problems that limit movement, or decreased activity levels

- Are bedridden

- Cannot move their limbs because of stroke or other brain disease

- Are in a place that lacks gravity, such as during space flights

Pathologic atrophy is seen with aging, starvation, and adverse effects of long-term use of corticosteroids. Neurogenic atrophy is the most severe type of muscle atrophy. It can be from an injured or diseased nerve that connects to the muscle. Examples of neurogenic atrophy are spinal cord injuries and polio.[8]

Although physiologic atrophy due to disuse can often be reversed with exercise, muscle atrophy caused by age is more complex. The effects of age-related atrophy are especially pronounced in people who are sedentary because the loss of muscle results in functional impairments such as trouble with walking, balance, and posture. These functional impairments can cause decreased quality of life and injuries due to falls.[9]

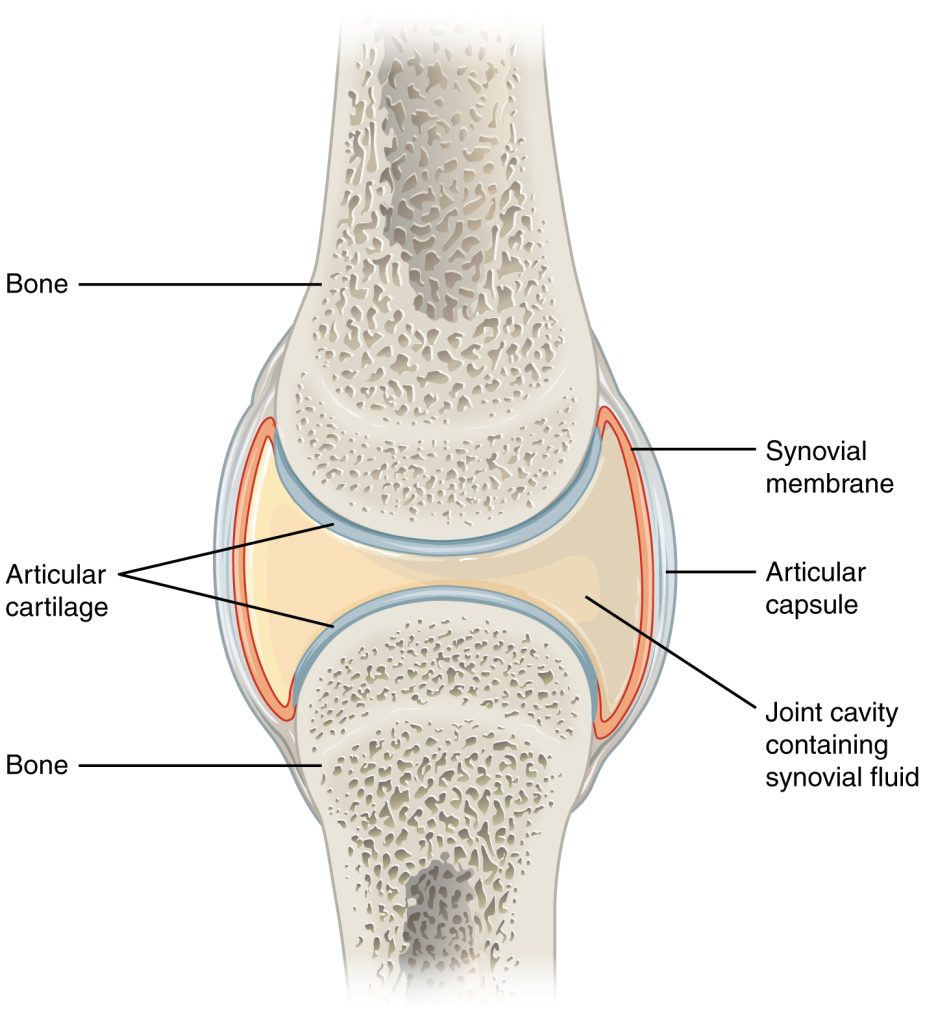

Joints

Joints are the location where bones come together. Many joints allow for movement between the bones. Synovial joints are the most common type of joint in the body. Synovial joints have a fluid-filled joint cavity where the articulating surfaces of the bones contact and move smoothly against each other. See Figure 13.4[10] for an illustration of a synovial joint. Articular cartilage is smooth, white tissue that covers the ends of bones where they come together and allows the bones to glide over each other with very little friction. Articular cartilage can be damaged by injury or normal wear and tear. Lining the inner surface of the articular capsule is a thin synovial membrane. The cells of this membrane secrete synovial fluid, a thick, slimy fluid that provides lubrication to further reduce friction between the bones of the joint.[11]

Types of Synovial Joints

There are six types of synovial joints. See Figure 13.5[12] for an illustration of the types of synovial joints. Some joints are relatively immobile but stable. Other joints have more freedom of movement but are at greater risk of injury. For example, the hinge joint of the knee allows flexion and extension, whereas the ball and socket joint of the hip and shoulder allows flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and rotation. The knee, hip, and shoulder joints are commonly injured and are discussed in more detail in the following subsections.

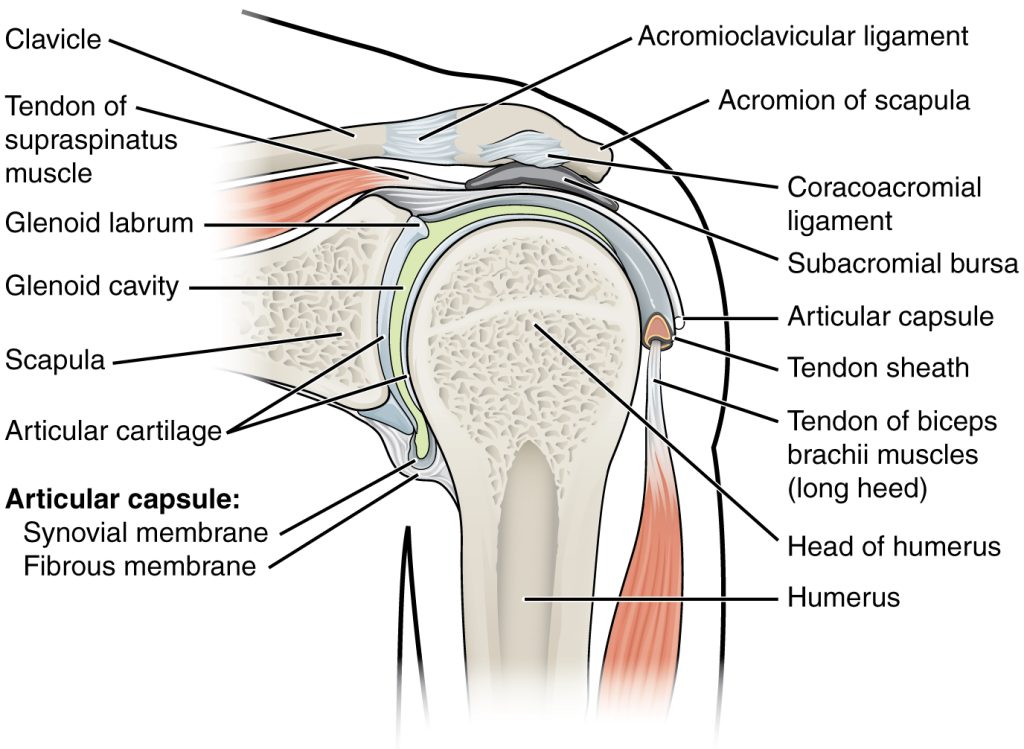

Shoulder Joint

The shoulder joint is a ball-and-socket joint formed by the articulation between the head of the humerus and the glenoid cavity of the scapula. This joint has the largest range of motion of any joint in the body. See Figure 13.6[13] to review the anatomy of the shoulder joint. Injuries to the shoulder joint are common, especially during repetitive abductive use of the upper limb such as during throwing, swimming, or racquet sports.[14]

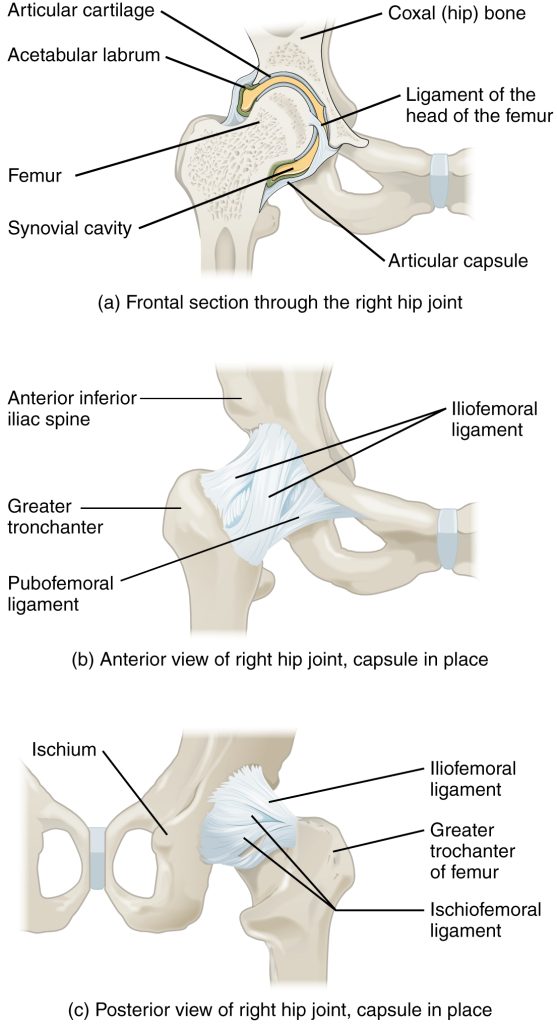

Hip Joint

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint between the head of the femur and the acetabulum of the hip bone. The hip carries the weight of the body and thus requires strength and stability during standing and walking.[15]

See Figure 13.7[16] for an illustration of the hip joint.

A common hip injury in older adults, often referred to as a “broken hip,” is actually a fracture of the head of the femur. Hip fractures are commonly caused by falls.[17]

See more information about hip fractures under the “Common Musculoskeletal Conditions” section.

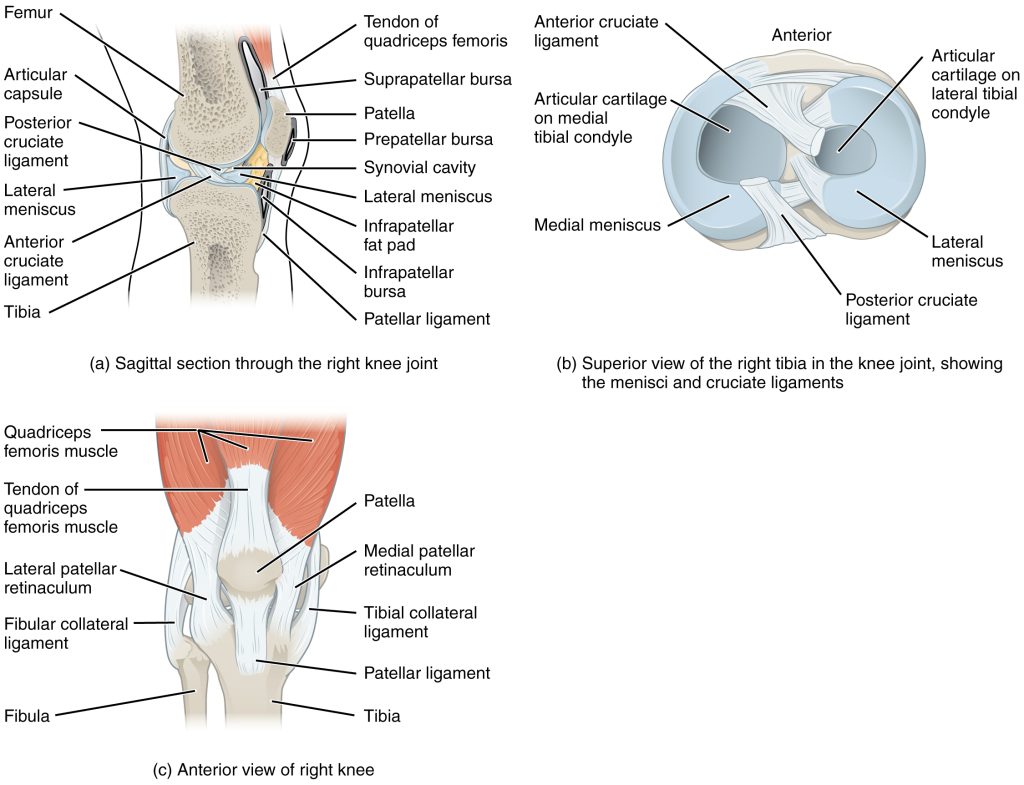

Knee Joint

The knee functions as a hinge joint that allows flexion and extension of the leg. In addition, some rotation of the leg is available. See Figure 13.8[18] for an illustration of the knee joint. The knee is vulnerable to injuries associated with hyperextension, twisting, or blows to the medial or lateral side of the joint, particularly while weight-bearing.[19]

The knee joint has multiple ligaments that provide support, especially in the extended position. On the outside of the knee joint are the lateral collateral, medial collateral, and tibial collateral ligaments. The lateral collateral ligament is on the lateral side of the knee and spans from the lateral side of the femur to the head of the fibula. The medial collateral ligament runs from the medial side of the femur to the medial tibia. The tibial collateral ligament crosses the knee and is attached to the articular capsule and to the medial meniscus. In the fully extended knee position, both collateral ligaments are taut and stabilize the knee by preventing side-to-side or rotational motions between the femur and tibia.[20]

Inside the knee joint are the anterior cruciate ligament and posterior cruciate ligament. These ligaments are anchored inferiorly to the tibia and run diagonally upward to attach to the inner aspect of a femoral condyle. The posterior cruciate ligament supports the knee when it is flexed and weight-bearing such as when walking downhill. The anterior cruciate ligament becomes tight when the knee is extended and resists hyperextension.[21]

The patella is a bone incorporated into the tendon of the quadriceps muscle, the large muscle of the anterior thigh. The patella protects the quadriceps tendon from friction against the distal femur. Continuing from the patella to the anterior tibia just below the knee is the patellar ligament. Acting via the patella and patellar ligament, the quadriceps is a powerful muscle that extends the leg at the knee and provides support and stabilization for the knee joint.

Located between the articulating surfaces of the femur and tibia are two articular discs, the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus. Each meniscus is a C-shaped fibrocartilage that provides padding between the bones.[22]

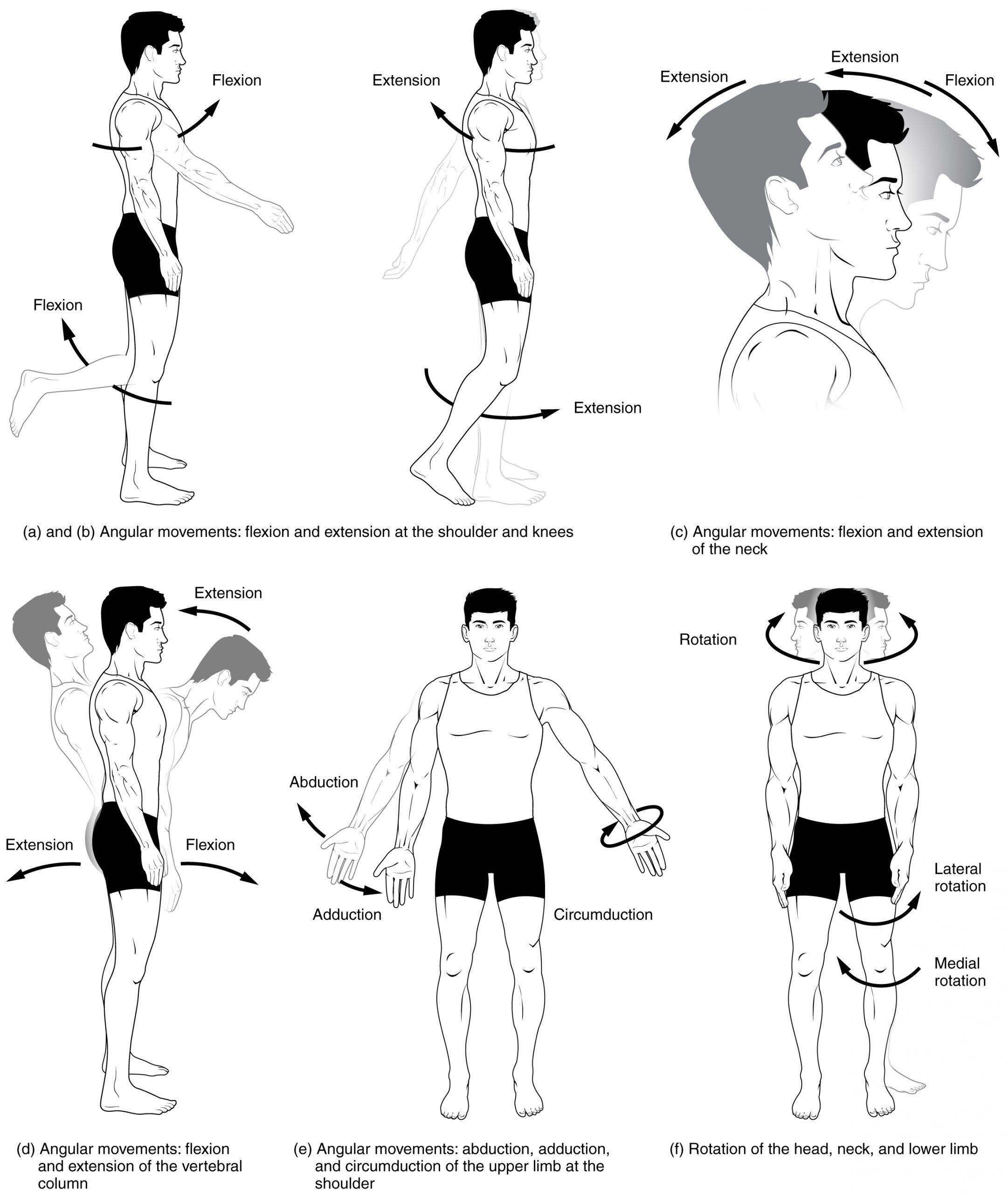

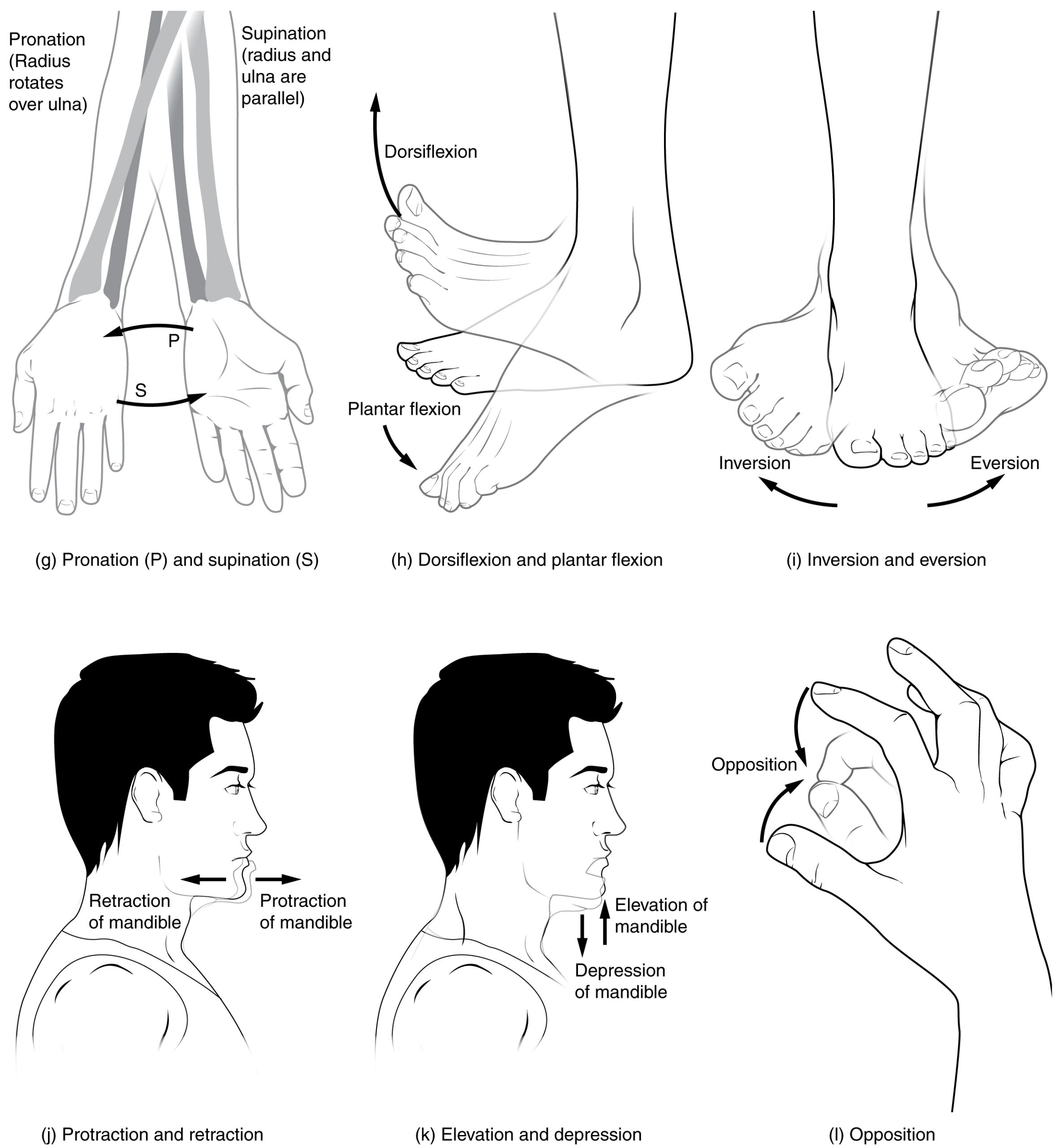

Joint Movements

Several movements may be performed by synovial joints. Abduction is the movement away from the midline of the body. Adduction is the movement toward the middle line of the body. Extension is the straightening of limbs (increase in angle) at a joint. Flexion is bending the limbs (reduction of angle) at a joint. Rotation is a circular movement around a fixed point. See Figures 13.9[23] and 13.10[24] for images of the types of movements of different joints in the body.

Joint Sounds

Sounds that occur as joints are moving are often referred to as crepitus. There are many different types of sounds that can occur as a joint moves, and patients may describe these sounds as popping, snapping, catching, clicking, crunching, cracking, crackling, creaking, grinding, grating, and clunking. There are several potential causes of these noises such as bursting of tiny bubbles in the synovial fluid, snapping of ligaments, or a disease condition. While assessing joints, be aware that joint noises are common during activity and are usually painless and harmless, but if they are associated with an injury or are accompanied by pain or swelling, they should be reported to the health care provider for follow-up.[25]

View a supplementary video from Physitutors called Why Your Knees Crack | Joint Crepitations.[26]