6.7 Pneumonia

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Overview

Pathophysiology

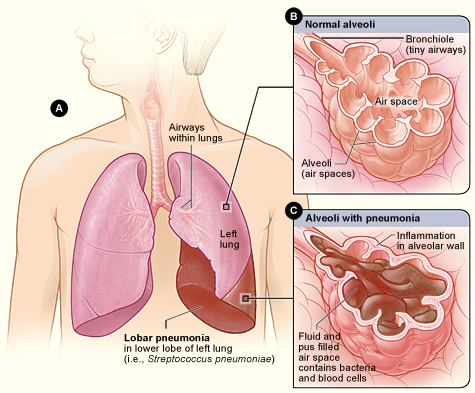

Pneumonia is a common respiratory infection that can affect people of all ages. It is characterized by inflammation and infection within the alveoli, causing them to fill with fluid or purulent material, resulting in a productive cough, fever, chills, and difficulty breathing. Pneumonia differs from chronic conditions like asthma and COPD in that it is an acute infection. Pneumonia can range in seriousness from mild to life-threatening. It is most serious for infants and young children, people older than age 65, and people with chronic health problems like COPD or weakened immune systems.[1],[2]

Pneumonia can be caused by a variety of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Common bacteria that cause pneumonia include Streptococcus pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. A variety of respiratory viruses such as rhinovirus, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and COVID-19 also cause pneumonia. Fungi can also cause pneumonia, especially in individuals with weakened immune systems.[3] See Figure 6.23[4] for an illustration of pneumonia.

Classifications of Pneumonia

Pneumonia is classified according to the type of microorganism that caused it and the location where the individual developed the infection. This classification affects the medical treatment plan and the antibiotics used to treat it. Classifications of pneumonia include the following[5]:

- Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) refers to pneumonia that began in the community (not in a hospital).

- Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) refers to pneumonia that began during or immediately following a stay in a health care setting. Health care settings include hospitals, long-term care facilities, and dialysis centers.

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) refers to when someone gets pneumonia during or after being on a ventilator.

- Aspiration pneumonia refers to when someone inhales food, drink, vomit, saliva, or medication into the lungs instead of swallowing it. Risk factors for aspiration pneumonia include difficulty swallowing, a brain injury that causes an impaired gag reflex, oversedation by medications, or excessive alcohol or drug use.[6]

Assessment

Clinical manifestations of pneumonia vary in severity and can be influenced by factors such as the causative pathogen, as well as the individual’s age, overall health, and underlying medical conditions. See Table 6.7 for a summary of clinical manifestations of pneumonia across body systems. It is essential for nurses to recognize these symptoms early and notify the health care provider of suspected pneumonia.

Table 6.7. Clinical Manifestations of Pneumonia[7],[8]

| Body System | Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Respiratory | Cough (nonproductive or productive of purulent sputum), dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain (worse with deep breathing or coughing), labored breathing, tachypnea, fine crackles on auscultation, and decreased pulse oximetry readings |

| Cardiovascular | Tachycardia |

| Nervous | New onset confusion or altered mental status |

| Gastrointestinal | Decreased appetite |

| Musculoskeletal | Muscle aches and joint pain, especially for viral causes, fatigue, and weakness |

| Integumentary | Diaphoresis and cyanosis (bluish or grayish skin due to lack of oxygen) |

| General | Fever, shaking chills (most often with high temperature), malaise (general discomfort or uneasiness), and weight loss (often due to reduced appetite) |

Diagnostic Testing

Pneumonia is typically diagnosed through a combination of clinical assessment, medical history, and diagnostic tests. Common diagnostic tests used to diagnose pneumonia are as follows:

- Chest X-Ray: A chest X-ray identifies areas of the lung that are inflamed or filled with fluid, called “consolidation.” The X-ray provides a visual confirmation of the infection and its extent in the lungs.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): An elevated white blood cell count is often an indicator of an infection.

- Sputum Culture: A sputum sample (mucus coughed up from the lungs) may be collected for laboratory testing to identify the causative microorganism. This is especially important for selecting appropriate antibiotic treatment.

In serious cases of pneumonia, especially for hospitalized clients, additional diagnostic testing may be performed[9],[10]:

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG): ABG testing assesses the amount of dissolved oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the blood and determines the severity of hypoxemia and hypercapnia.

- Bronchoscopy: In cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or when there is a need to examine the airways directly, a bronchoscopy may be performed. This involves passing a thin, flexible tube with a camera through the airways to visualize the lungs and collect samples.

- CT Scan: A computed tomography (CT) scan may be performed to provide more detailed images of the lungs.

- Blood Cultures: Blood cultures may be performed to determine if bacterial pneumonia has spread to the blood.

- Pleural Fluid Culture: A pleural fluid culture may be taken using a procedure called thoracentesis, which is a procedure where a health care provider uses a needle to take a sample of fluid from the pleural space between the lungs and chest wall.

Review normal reference ranges for common diagnostic tests in “Appendix A – Normal Reference Ranges.”

Nursing Diagnoses

Nursing priorities for clients with pneumonia are focused on improving respiratory function, alleviating symptoms, and supporting recovery while preventing complications.

Nursing diagnoses for clients with pneumonia are formulated based on the client’s assessment data, medical history, and specific needs. Common nursing diagnoses include the following[11]:

- Ineffective Airway Clearance

- Impaired Gas Exchange

- Ineffective Thermoregulation

- Decreased Activity Intolerance

- Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume

Outcome Identification

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and creating expected outcome statements customized for the client’s specific needs. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions.

Sample expected outcomes for common nursing diagnoses related to pneumonia are as follows:

- The client will maintain oxygen saturation within the target range, typically above 92%.

- The client’s signs of infection, such as fever above 101 degrees Fahrenheit and elevated white blood cell count, will improve with treatment.

- The client’s reported level of dyspnea at rest and with activity will decrease with treatment.

Interventions

Medical Interventions

Medical interventions for pneumonia aim to treat the underlying infection, alleviate symptoms, and support the client’s recovery.

Medication Therapy

A variety of medications may be prescribed for clients with pneumonia[12],[13]:

- Antibiotic Therapy: Antibiotics are prescribed if the suspected or confirmed causative agent is bacteria. The choice of antibiotic by the health care provider is based on the classification of pneumonia (i.e., CAP, HAP, VAP, or aspiration pneumonia). The antibiotic may be adjusted based on sputum or blood culture and sensitivity results. Duration of treatment is determined by the type of pneumonia and the client’s clinical response.

- Antiviral Medications: If pneumonia is caused by a viral infection, antiviral medications may be prescribed. These medications aim to reduce viral replication and severity of symptoms.

- Antifungal Medications: If pneumonia is caused by a fungal infection, antifungal medications are utilized to target and eliminate fungal pathogens, disrupting their ability to grow and reproduce.

- Bronchodilators: Bronchodilators, such as albuterol, may be administered to alleviate bronchoconstriction and improve airflow, especially in clients with concurrent obstructive lung diseases like asthma or COPD.

- Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids may be prescribed in specific cases to reduce inflammation in the airways and improve breathing.

- Antipyretics: Antipyretic medications (e.g., acetaminophen or ibuprofen) may be prescribed to reduce fever and discomfort.

- Pneumococcal and Influenza Vaccinations: To prevent future episodes of pneumonia, clients are encouraged to receive influenza, COVID, and pneumococcal vaccines.

- Oxygen Therapy: Supplemental oxygen is prescribed to maintain adequate oxygen saturation levels. Oxygen delivery methods vary based on the client’s needs and severity of respiratory distress.

- Fluid Intake: Clients are encouraged to increase fluid intake to maintain hydration and thin secretions, if not contraindicated. For hospitalized clients, IV fluids may be prescribed, especially if the client has a high fever, reduced oral intake, or difficulty swallowing.

Read additional information about oxygen equipment and safety measures in the “Oxygenation Therapy” chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Respiratory Therapies

Chest physiotherapy techniques, such as postural drainage and percussion, may be used to assist in clearing mucus and secretions from the airways. Vibratory positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy (i.e., flutter valves) may be prescribed for clients who need assistance in clearing mucus from their airways. Clients are encouraged to cough and deep breathe, and incentive spirometry devices may be prescribed to treat/prevent atelectasis. Review information about vibratory positive expiratory pressure therapy, coughing and deep breathing, and incentive spirometers in the “General Nursing Interventions Related to Respiratory Alterations” subsection earlier in this chapter.

Ventilation Support

In severe cases of pneumonia, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, commonly referred to as CPAP or BiPAP, or intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary to provide respiratory support.[14],[15] See Figure 6.24[16] for an image of a simulated client with a BiPAP mask in place.

Read more about CPAP, BiPAP, and mechanical ventilation in the “Oxygen Equipment” section of the “Oxygen Therapy” chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Pleural Procedures

In cases of pleural effusion (accumulation of fluid in the pleural cavity), procedures such as thoracentesis or chest tube insertion may be required.[17],[18]

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for pneumonia focus on promoting recovery, preventing complications, and preventing future illness.

Medication Management

Nurses safely administer prescribed antibiotics, antivirals, or antifungals that target the specific pathogen causing pneumonia. Antipyretic medications (e.g., acetaminophen or ibuprofen) are administered as needed to reduce fever and discomfort. Bronchodilators may be administered to alleviate bronchoconstriction and improve airflow, especially in clients with preexisting lung conditions. Nurses teach clients about the purpose of prescribed medications and the importance of taking the full course of antibiotics as directed.

Maintain Hydration

Nurses monitor fluid intake and output and for signs of fluid volume deficit. Clients are encouraged to maintain adequate hydration, especially if they have a fever, productive cough, or increased respiratory rate that can contribute to fluid loss. Clients are encouraged to drink at least two liters of water daily to loosen secretions, unless they are on a fluid restriction.

Assist With Respiratory Therapy

Nurses assist clients with techniques such as postural drainage, coughing and deep breathing, incentive spirometry, and/or vibratory pressure therapy, as prescribed. Effective coughing techniques are demonstrated and encouraged. Review enhanced breathing and coughing techniques in the “General Nursing Interventions Related to Respiratory Alterations” subsection earlier in this chapter.

Infection Control

Nurses implement appropriate infection control measures, including hand hygiene, personal protective equipment, and transmission-based precautions based on the infectious organism to prevent the spread of infection.

Immunizations

Nurses encourage clients to remain up-to-date on recommended vaccinations, including the pneumococcal vaccine for adults at risk and all those over age 65.

Review current information about “Recommended Vaccines By Age” from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Evaluation

During the evaluation stage, nurses determine the effectiveness of nursing interventions for a specific client. The previously identified expected outcomes are reviewed to determine if they were met, partially met, or not met by the time frames indicated. If outcomes are not met or only partially met by the time frame indicated, the nursing care plan is revised. Evaluation should occur every time the nurse implements interventions with a client, reviews updated laboratory or diagnostic test results, or discusses the care plan with other members of the interprofessional team.

![]() RN Recap: Pneumonia

RN Recap: Pneumonia

View a brief YouTube video overview of pneumonia[19]:

Media Attributions

- Lobar_pneumonia_illustrated

- Ramirez, J. A. (2023). Overview of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 4, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is pneumonia? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/pneumonia#:~:text=Pneumonia%20is%20an%20infection%20that,or%20fungi%20may%20cause%20pneumonia ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, September 30). Pneumonia. https://www.cdc.gov/pneumonia/index.html ↵

- “Lobar_pneumonia_illustrated.jpg” by Heart, Lung and Blood Institute is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, September 30). Pneumonia. https://www.cdc.gov/pneumonia/index.html ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2020, June 13). Pneumonia. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pneumonia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354204 ↵

- Ramirez, J. A. (2023). Overview of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 4, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is pneumonia? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/pneumonia#:~:text=Pneumonia%20is%20an%20infection%20that,or%20fungi%20may%20cause%20pneumonia ↵

- Ramirez, J. A. (2023). Overview of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 4, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is pneumonia? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/pneumonia#:~:text=Pneumonia%20is%20an%20infection%20that,or%20fungi%20may%20cause%20pneumonia ↵

- Flynn Makic, M. B., & Martinez-Kratz, M. R. (2023). Ackley and Ladwig’s Nursing diagnosis handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care (13th ed.). Elsevier. ↵

- Ramirez, J. A. (2023). Overview of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 4, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is pneumonia? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/pneumonia#:~:text=Pneumonia%20is%20an%20infection%20that,or%20fungi%20may%20cause%20pneumonia ↵

- Ramirez, J. A. (2023). Overview of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 4, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is pneumonia? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/pneumonia#:~:text=Pneumonia%20is%20an%20infection%20that,or%20fungi%20may%20cause%20pneumonia ↵

- “Simulated patient wearing a BiPAP mask” by Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Ramirez, J. A. (2023). Overview of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved October 4, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March 24). What is pneumonia? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/pneumonia#:~:text=Pneumonia%20is%20an%20infection%20that,or%20fungi%20may%20cause%20pneumonia ↵

- Open RN Project. (2024, June 23). Health Alterations - Chapter 6 - Pneumonia [Video]. You Tube. CC BY-NC 4.0 https://youtu.be/PDbrPS3X50I?si=BGo8htPvDJIqfW82 ↵

There are several types of equipment a nurse may use when providing oxygen therapy to a patient. Each device is described in detail below.

Pulse Oximeter

A pulse oximeter is a commonly used portable device used to obtain a patient’s oxygen saturation level at the bedside or in a clinic. See Figure 11.6[1] for an image of a portable pulse oximeter. The pulse oximeter, commonly referred to as a “Pulse Ox,” is an electronic device that noninvasively measures the oxygen saturation of hemoglobin in a patient’s red blood cells, referred to as SpO2. The normal range for SpO2 for an adult without an underlying respiratory condition is above 92%. The pulse oximeter analyzes light produced by the probe as it passes through the finger to determine the saturation level of the hemoglobin molecule.

Pulse oximetry readings can be inaccurate for several reasons and must be interpreted using the nurse's clinical judgment. The most common cause of inaccuracy with pulse oximeters is motion artifact. Patient movement can cause pulsatile venous flow to be incorrectly measured as arterial pulsations, thus producing false oximetry and pulse-rate readings. Another common cause of inaccuracy is poor peripheral perfusion. Poor peripheral perfusion can be caused by conditions such cardiac and vascular disease. In these situations, use a specific pulse oximeter probe for the forehead, bridge of nose, or earlobe to obtain the reading. In any clinical situation where the patient's fingertips are cool or cold, attempt to warm them by using moist heat or a warm blanket, and then apply the pulse oximetry probe when the fingers are warmed for a more accurate reading. Nail polish can also cause an inaccurate pulse oximetry reading and must be removed before placing the probe. Finally, in emergency situations such as carbon monoxide poisoning, other molecules besides oxygen can attach to hemoglobin and cause a falsely high SpO2 reading even though the patient doesn't have enough oxygen to meet metabolic demands.[2]

Oxygen Flow Meter

In inpatient settings, rooms are equipped with wall-mounted oxygen supply outlets that are nationally standardized in a green color, whereas air outlets are standardized with a yellow color. Oxygen flow meters are attached to the green oxygen outlets, and then the oxygenation device is attached to the flow meter. See Figure 11.7[3] for an image of an oxygen flow meter. An oxygen flow meter consists of a glass cylinder containing a steel ball with an opening through which oxygen from the supply source is injected through an adapter. This adapter is commonly referred to as a “tree” because of its appearance. Oxygen is turned on, and the flow rate of oxygen is controlled by turning the green valve on the side of the glass cylinder. The flow rate is set according to the location of a steel ball inside the cylinder and the numbered lines on the glass cylinder. The line corresponding to the ordered liter flow rate should intersect the middle of the metal ball in the flow meter. For example, in Figure 11.7 the flow rate is currently set at 2 liter per minute (L/min). It is essential to implement safety precautions whenever oxygen is used. Read more about "Safety with Oxygen Therapy" later in this section.

Portable Oxygen Supply Devices

Portable oxygen tanks are commonly used when transporting a patient to procedures within the hospital or to other agencies. See Figure 11.8[4] for an image of a portable oxygen tank. Oxygenation devices are connected to the tank in a similar manner as the wall-mounted oxygen flow meter. It is crucial for nurses and transporters to ensure the tank has an adequate amount of oxygen for use during transport, is turned on, and the appropriate flow rate is set.

Instead of oxygen tanks, oxygen concentrators are commonly used by patients in their home environment. See Figure 11.9[5] for an image of a home oxygen concentrator. Oxygen concentrators are also produced in portable sizes that are lightweight and easy for patient use while travelling and mobile in the community. See Figure 11.10[6] for an image of a portable oxygen concentrator. Oxygen concentrators work by taking the 21% concentration of oxygen in the air, running it through a molecular sleeve to remove the nitrogen and concentrating the oxygen to a 96% level, thus producing between 1 and 6 liters per minute of oxygen. Oxygen concentrators may provide pulse flow or continuous flow. Pulse flow only occurs on inhalation, whereas continuous flow delivers oxygen throughout the entire breath cycle. Pulse versions are the most lightweight because oxygen is provided only as needed by the patient.[7]

Nasal Cannula

A nasal cannula is the simplest oxygenation device and consists of oxygen tubing connected to two short prongs that are inserted into the patient’s nares. See Figure 11.11[8] for an image of a nasal cannula. The tubing is connected to the flow meter of the oxygen supply source. To prevent drying out the patient's mucus membranes, humidification may be added for hospitalized patients receiving oxygen flow rates greater than 4 L/minute or for those receiving oxygen therapy for longer periods of time.[9]

Nasal cannulas are the most common type of oxygen equipment. They are used for short- and long-term therapy (i.e., COPD patients) and are best used with stable patients who require low amounts of oxygen.

Flow rate: Nasal cannulas can have a flow rate ranging from 1 to 6 liters per minute (L/min), with a 4% increase in FiO2 for every liter of oxygen, resulting in range of fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) levels of 24-44%.

Advantages: Nasal cannulas are easy to use, inexpensive, and disposable. They are convenient because the patient can talk and eat while receiving oxygen.

Limitations: The nasal prongs of nasal cannula are easily dislodged, especially when the patient is sleeping. The tubing placed on the face can cause skin breakdown in the nose and above the ears, so the nurse must vigilantly monitor these areas. Based on agency policy, the nurse should add padding to the oxygen tubing as needed to avoid skin breakdown and may apply a water-based lubricant to prevent drying. However, petroleum-based lubricant should not be used due to the risk of flammability. Nasal cannulas are not as effective if the patient is a mouth breather or has blocked nostrils, a deviated septum, or nasal polyps.[10]

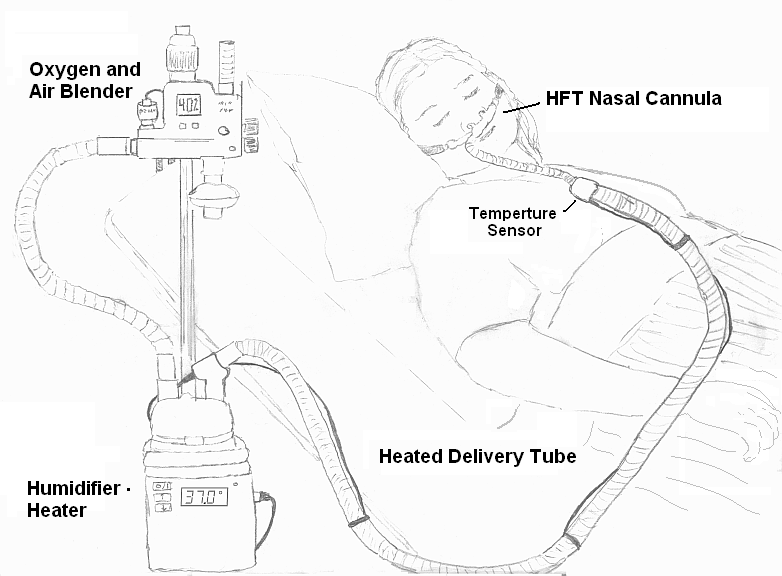

High-Flow Nasal Cannula

High-flow nasal cannula therapy is an oxygen supply system capable of delivering up to 100% humidified and heated oxygen at a flow rate of up to 60 liters per minute.[11] Patients with high-flow nasal cannulas are generally in critical condition and require advanced monitoring. See Figure 11.12[12] for an illustration of a high-flow nasal cannula system that is initially set up by a respiratory therapist and then maintained by a nurse.

Simple Mask

A simple mask fits over the mouth and nose of the patient and contains exhalation ports (i.e., holes on the side of the mask) through which the patient exhales carbon dioxide. These holes should always remain open. The mask is held in place by an elastic band placed around the back of the head. It also has a metal piece near the top that can be pinched and shaped over the patient's nose to create a better fit. Humidified air may be attached if the oxygen concentrations are drying for the patient. See Figure 11.13[13] for an image of a simple face mask.

Flow Rate: Simple masks should be set to a flow rate of 6 to 10 L/min, resulting in oxygen concentration (FiO2) levels of 35%-50%. The flow rate should never be set below 6 L/min because this can result in the patient rebreathing their exhaled carbon dioxide.

Advantages: Face masks are used to provide moderate oxygen concentrations. Their efficiency in oxygen delivery depends on how well the mask fits and the patient’s respiratory demands.

Disadvantages: Face masks must be removed when eating, and they may feel confining for some patients who feel claustrophobic with the mask on.[14]

Non-Rebreather Mask

A non-rebreather mask consists of a mask attached to a reservoir bag that is attached with tubing to a flow meter. See Figure 11.14[15] for an image of a non-rebreather mask. It has a series of one-way valves between the mask and the bag and also on the covers on the exhalation ports. The reservoir bag should never totally deflate; if the bag deflates, there is a problem and immediate intervention is required. The one-way valves function so that on inspiration, the patient only breathes in from the reservoir bag; on exhalation, carbon dioxide is directed out through the exhalation ports. Non-rebreather masks are used for patients who can breathe on their own but require higher concentrations of oxygen to maintain satisfactory blood oxygenation levels.

Flow rate: The flow rate for a non-rebreather mask should be set to deliver a minimum of 10 to 15 L/minute. The reservoir bag should be inflated prior to placing the mask on the patient. With a good fit, the non-rebreather mask can deliver between 60% and 80% FiO2.

Advantages: Non-rebreather masks deliver high levels of oxygen noninvasively to patients who can otherwise breathe unassisted.

Disadvantages: Due to the one-way valves in non-rebreather masks, there is a high risk of suffocation if the gas flow is interrupted. The mask requires a tight seal and may feel hot and confining to the patient. It will interfere with talking, and the patient cannot eat with the mask on.

Partial Rebreather Mask

The partial rebreather mask looks very similar to the non-rebreather mask. The difference between the masks is a partial rebreather mask does not contain one-way valves, so the patient’s exhaled air mixes with their inhaled air. A partial rebreather mask requires 10-15 L/min of oxygen, but only delivers 35-50% FiO2.

Venturi Mask

Venturi masks are indicated for patients who require a specific amount of supplemental oxygen to avoid complications, such as those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Different types of adaptors are attached to a face mask that set the flow rate to achieve a specific FiO2 ranging from 24% to 60%. Venturi adapters are typically set up by a respiratory therapist, but in some facilities, they may be set up by a nurse according to agency policy.

Flow rate: The flow rate depends on the adaptor and does not correspond to the flow meter. Consult with a respiratory therapist before changing the flow rate.

Advantages: A specific amount of FiO2 is delivered to patients whose breathing status may be affected by high levels of oxygen.

Oxymask

An oxymask is an oxygen delivery device that has an open design that eliminates the need for valves and reservoirs. O2 flow is directed towards the nose and mouth. Large openings in the mask allow CO2 to escape, decrease claustrophobia, increase ability to communicate, and allow for delivery of PO fluids and medications without removing the mask.

Flow rate: An oxymask can deliver 24-90% oxygen concentration on 1-15 LPM oxygen, which increases flexibility and safety of the product.

Advantages: The oxymask increases flexibility and safety due to variable oxygen flow rates. It also can decrease claustrophobia and increase the ability to communicate without removing the mask.

Oxymizer

An oxymizer is a special nasal cannula that provides a larger luminal diameter in combination with an oxygen reservoir. The oxymizer is designed as either a moustache or pendant style. Some patients don’t like the weight of the device, which is greater due to the oxygen reservoir and tubing size.

Flow rate: The flow rate is 1/4 to 1/2 of the previous flow rate required. The oxymizer can deliver up to 15 LPM.

Advantages: The oxymizer is able to help maintain adequate O2 saturations in hypoxic patients with a lower flow rate, resulting in reduced O2 costs, longer portable O2 sources, and decreased nasal irritation and dryness.

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP)

A continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device is used for people who are able to breathe spontaneously on their own but need help in keeping their airway unobstructed, such as those with obstructive sleep apnea. (See Table 11.2c in the “Basic Concepts of Oxygenation” section for more information about obstructive sleep apnea.) The CPAP device consists of a special mask that covers the patient’s nose, or nose and mouth, and is attached to a machine that continuously applies mild air pressure to keep the patient’s airways from collapsing.

A prescription is required for a CPAP device in the hospital or patient’s home environment. In the hospital, the FiO2 is set up with the CPAP mask by the respiratory therapist. In a home setting, an adapter is added so that oxygen is attached using a flow meter with preprogrammed settings so the patient and/or nurse are only required to turn the machine on before sleeping and off upon awakening. It is important to keep the mask and tubing clean to prevent infection, so be sure to follow agency policy for cleaning the equipment regularly. If a humidifier is attached, distilled water or sterile water should be used to fill it, but never tap water. See Figure 11.15[16] for an illustration of a patient wearing a CPAP device while sleeping.

View a supplementary YouTube video from the FDA on CPAP Tips[17]

BiPAP

A bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) device is similar to a CPAP device in that it is used to prevent airways from collapsing, but BiPAP devices have two pressure settings. One setting occurs during inhalation and a lower pressure setting is used during exhalation. Patients using BiPAP devices in their home environment for obstructive sleep apnea often find these two pressures more tolerable because they don’t have to exhale against continuous pressure. In acute-care settings, BiPAP devices are also used for patients in acute respiratory distress as a noninvasive alternative to intubation and mechanical ventilation and are managed by respiratory therapists. BiPAP devices in home settings are set up in a similar manner as CPAP machines for ease of use. See Figure 11.16[18] for an image of a simulated patient wearing a BiPAP mask in a hospital setting with continuous pulse oximetry monitoring.

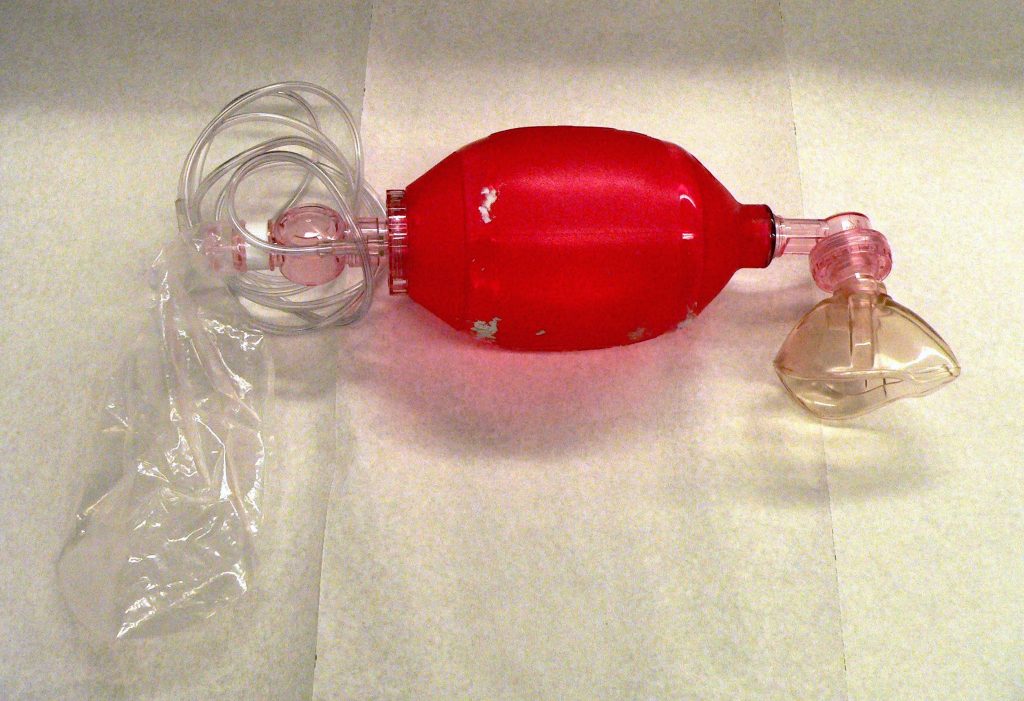

Bag Valve Mask (Ambu Bag)

A bag valve mask, commonly known as an “Ambu bag,” is a handheld device used in emergency situations for patients who are not breathing (respiratory arrest) or who are not breathing adequately (respiratory failure). In this manner, this device is different from the other devices because it assists with ventilation, the movement of air into and out of the lungs, as well as oxygenation. See Figure 11.17[19] for an image of a bag valve mask. Bag valve masks are produced in different sizes for infants, children, and adults to prevent lung injury, so it is important to use the correct size for the patient.

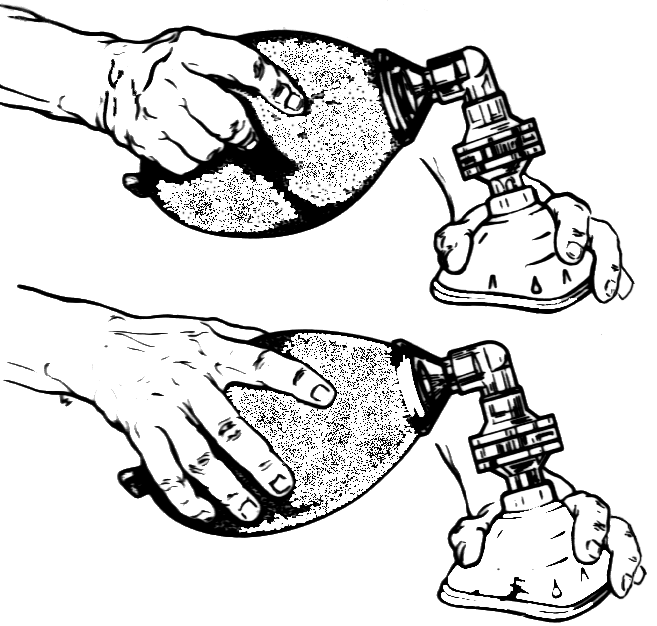

When using a bag mask valve, the rescuer manually compresses the bag to force air into the lungs. Squeezing the bag once every 5 to 6 seconds for an adult or once every 3 seconds for an infant or child provides an adequate respiratory rate. In inpatient settings, the bag mask valve is attached to an oxygen supply to increase the concentration of oxygenation provided with each breath. See Figure 11.18[20] for an illustration of operating a bag valve mask.

It is vital to obtain a tight seal of the mask to the patient’s face, but this is difficult for a single rescuer to achieve. Therefore, two rescuers are recommended; one rescuer performs a jaw thrust maneuver, secures the mask to the patient's face with both hands, and focuses on maintaining a leak-proof mask seal, while the other rescuer squeezes the bag and focuses on the amount and the timing.

Flow rate: The flow rate for a bag valve mask attached to an oxygen source should be set to 15 L/minute, resulting in FiO2 of 100%.

Advantages: A bag valve mask is portable and provides immediate assistance to patients in respiratory failure or respiratory arrest. It also can be used to hyperoxygenate patients before procedures that can cause hypoxia, such as tracheal suctioning.

Disadvantages: The rate and depth of compression of the bag must be closely monitored to prevent injury to the patient. In the event of respiratory failure when the patient is still breathing, the bag compressions must be coordinated with the patient’s inhalations to ensure that oxygen is delivered, and asynchrony of breaths is prevented. Complications may also result from overinflating or overpressurizing the patient. Complications include lung injury or the inflation of the stomach that can lead to aspiration of stomach contents. Additionally, rescuers may tire after a few minutes of manually compressing the bag, resulting in less-than-optimal ventilation. Alternatively, an endotracheal tube (ET) can be inserted by an advanced practitioner to substitute for the mask portion of this device. See more information about endotracheal tubes below.

Endotracheal Intubation

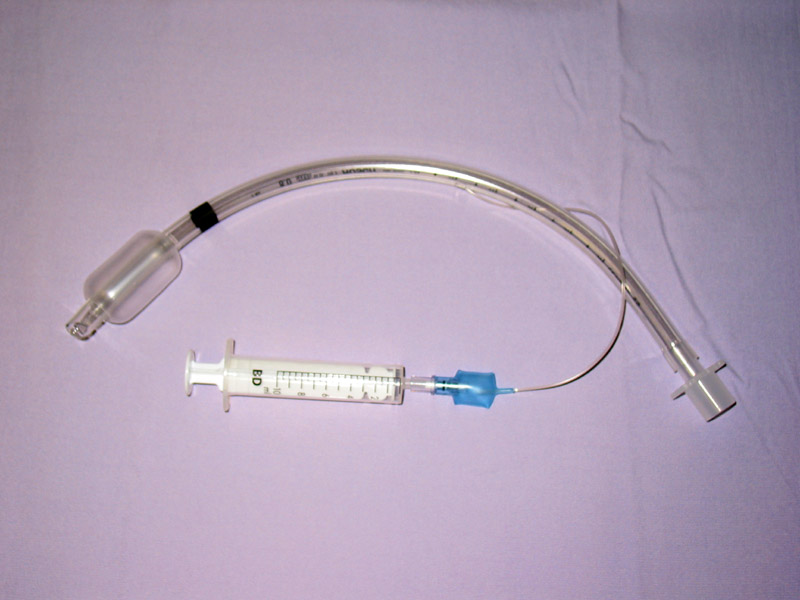

When a patient is receiving general anesthesia prior to a procedure or surgery or is experiencing respiratory failure or respiratory arrest, an endotracheal tube (ET) is inserted by an advanced practitioner, such as a respiratory therapist, paramedic, or anesthesiologist, to maintain a secure airway. The ET tube is sealed within the trachea with an inflatable cuff, and oxygen is supplied via a bag valve mask or via mechanical ventilation. See Figure 11.19[21] for an image of a cuffed endotracheal tube.

Mechanical Ventilator

A mechanical ventilator is a machine attached to an endotracheal tube to assist or replace spontaneous breathing. Mechanical ventilation is termed invasive because it requires placement of a device inside the trachea through the mouth, such as an endotracheal tube. Mechanical ventilators are managed by respiratory therapists via protocol or provider order. FiO2 can be set from 21-100%. Nurses collaborate with respiratory therapists and the health care providers regarding the overall care of the patient on a mechanical ventilator. See Figure 11.20[22] for an image of a simulated patient who is intubated with an endotracheal tube and attached to a mechanical ventilator.

Tracheostomy

A tracheostomy is a surgically made hole called a stoma that goes from the front of the patient’s neck into the trachea. A tracheostomy tube is placed through the stoma and directly into the trachea to maintain an open (patent) airway and to administer oxygen. A tracheostomy may be performed emergently or as a planned procedure. Read more about tracheostomies in the "Tracheostomy Care and Suctioning" chapter.

Flow Rates and Oxygen Percentages

When administering oxygen to a patient, it is important to ensure that oxygen flow rates are appropriately set according to the type of administration device. Review Table 11.3a to review appropriate settings for various types of oxygenation devices.

Table 11.3a Settings of Oxygenation Devices

| Device | Flow Rates and Oxygen Percentage |

|---|---|

| Nasal Cannula | Flow rate: 1-6 L/min

FiO2: 24% to 44% |

| High-Flow Nasal Cannula | Flow rate: up to 60 L/min

FiO2: Up to 100% |

| Simple Mask | Flow rate: 6-10 L/min

FiO2: 28% to 50% |

| Non-Rebreather Mask | Flow rate: 10 to 15 L/min

FiO2: 60-80% Safety Note: The reservoir bag should always be partially inflated. |

| CPAP, BiPAP, Venturi Mask, Mechanical Ventilator | Use the settings provided by the respiratory therapist and/or provider order.

|

| Bag Valve Mask | Flow rate: 15 L/min

FiO2: 100% Squeeze the bag once every 5 to 6 seconds for an adult or once every 3 seconds for an infant or child. |

Safety With Oxygen Therapy

Oxygen therapy supports life, but it also supports fire. While there are many benefits to oxygen therapy, there are also many hazards. Oxygen must be administered cautiously and according to the safety guidelines in Table 11.3b.[23]

Table 11.3b Oxygen Therapy Safety Guidelines

| Guideline | Additional Information |

|---|---|

| Remember that oxygen is a medication. | Oxygen is a medication and should not be adjusted without consultation with a physician or respiratory therapist. |

| Store oxygen cylinders correctly. | When using oxygen cylinders, store them upright, chained, or in appropriate holders so that they will not fall. Full oxygen tanks should be stored separately from partially full or empty oxygen tanks. |

| Use tank holders appropriately. | When transporting a patient, proper tank holders must be used per The Joint Commission guidelines. Tanks should never be placed on the patient’s bed. |

| Do not allow smoking near the oxygen devices. | Oxygen supports combustion. No smoking is permitted around any oxygen delivery devices in the hospital or home environment. |

| Keep oxygen cylinders away from heat sources. | Keep oxygen delivery systems at least 5 feet from any heat source. |

| Check for electrical hazards in the home or hospital prior to use. | Determine that electrical equipment in the room or home is in safe working condition. A small electrical spark in the presence of oxygen will result in a serious fire. The use of a gas stove, kerosene space heater, or smoker is unsafe in the presence of oxygen. Avoid items that may create a spark (e.g., electrical razor, hair dryer, synthetic fabrics that cause static electricity, or mechanical toys) with nasal cannula in use. Petroleum-based lubricants should not be used on the lips or around the nasal cannula. |

| Check levels of oxygen in portable tanks. | Check oxygen levels of portable tanks before transporting a patient to ensure that there is enough oxygen in the tank. |

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of a “Cardiovascular Assessment."[24]

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: stethoscope and watch with a second hand.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Conduct a focused interview related to cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disease.

- Ask relevant focused questions based on patient status. See Tables 9.3a and 9.3b for example questions.

- Inspect:

- Face, lips, and extremities for pallor or cyanosis

- Neck for jugular vein distension (JVD) in upright position or with head of bed at 30- or 45-degree angle

- Chest for deformities and wounds/scars on chest

- Bilateral arms/hands, noting color, warmth, movement, sensation (CWMS), edema, and color of nail beds

- Bilateral legs, noting CWMS, edema to lower legs and feet, presence of superficial distended veins, and color of nail beds

- Auscultate with both the bell and the diaphragm of the stethoscope over five auscultation areas of the heart. Auscultate the apical pulse at the fifth intercostal space, midclavicular line for one minute. Note the rate and rhythm. Identify the S1 and S2 sounds and follow up on any unexpected findings (e.g., extra sounds or irregular rhythm).

- Palpate the radial, brachial, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibialis pulses bilaterally. Palpate the carotid pulse one side at a time. Note presence/amplitude of pulse and any unexpected findings requiring follow-up.

- Palpate the nail beds on each extremity for capillary refill. Document the capillary refill time.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.