6.2 Review of Anatomy and Physiology of the Respiratory System

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

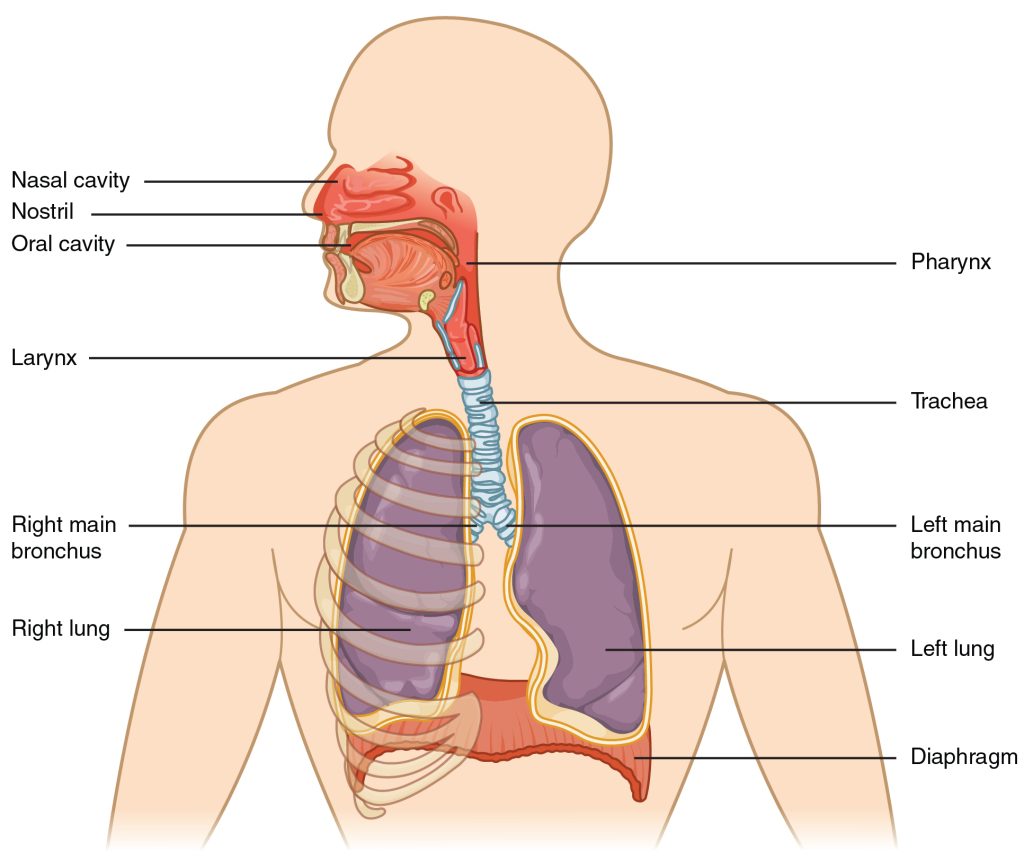

This section will review the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system. Common disorders affecting these anatomic structures are also introduced. See Figure 6.1[1] for an illustration of the major structures of the respiratory system.

Nose, Nasal Cavity, and Sinuses

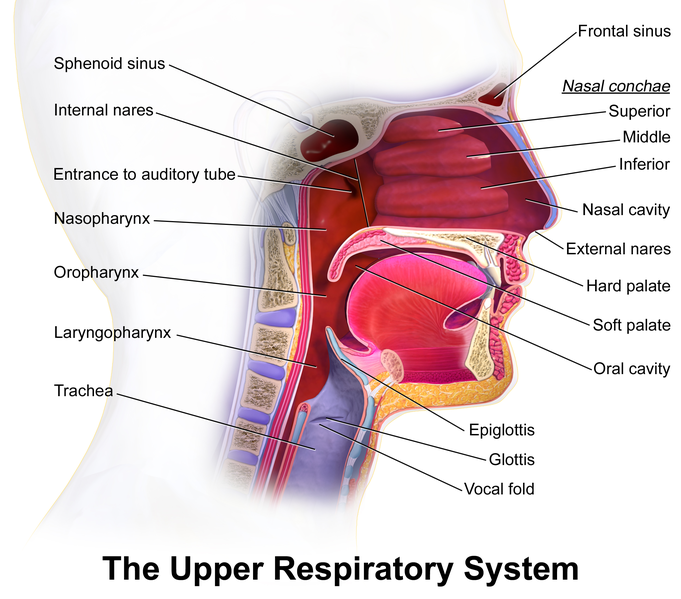

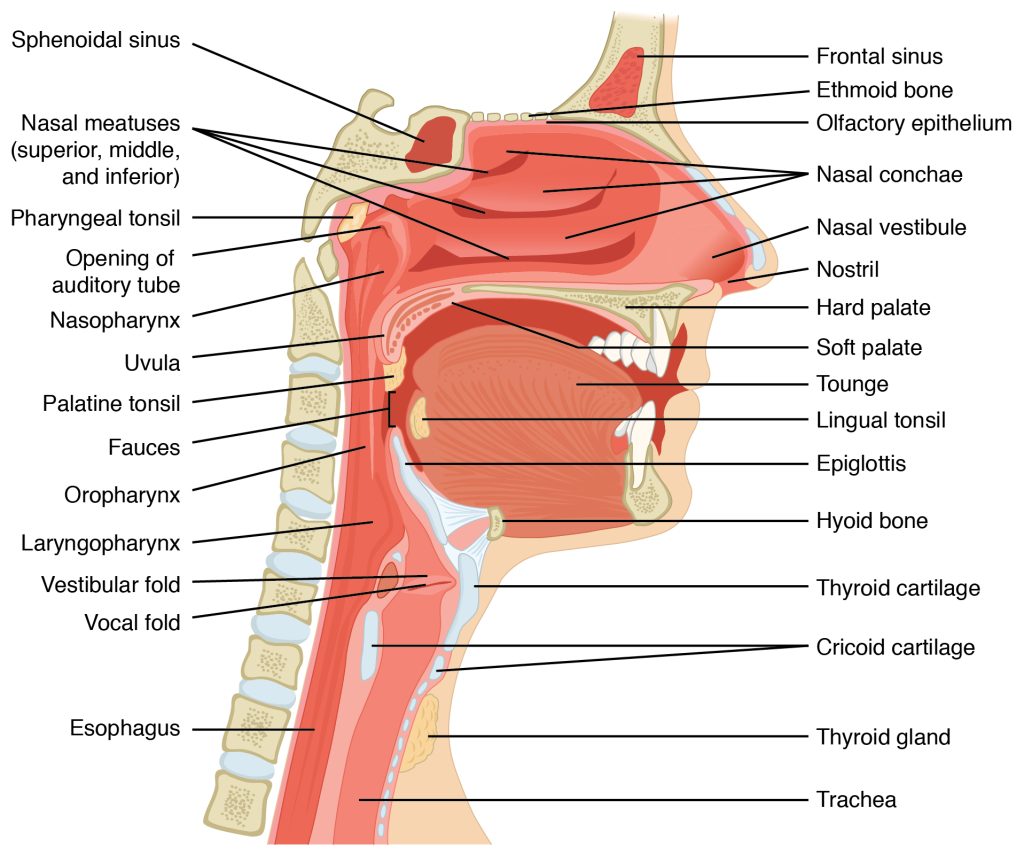

The upper respiratory system refers to the nose, nasal cavities, sinuses, pharynx, and larynx. See Figure 6.2[2] for an illustration of anatomic structures of the upper respiratory system. An upper respiratory infection (URI) refers to a viral infection of one or more of these structures.

The entrance and exit for the respiratory system are through the nose. The nostrils are the opening to the nose, also referred to as nares. The nares and nasal cavities are lined with mucous membranes, containing sebaceous glands and hair follicles that serve to prevent the passage of large debris, such as dirt, through the nasal cavity. Rhinorrhagia refers to bleeding from the nose, also called epistaxis. Rhinitis refers to inflammation of the nasal mucosa.

The nares open into the nasal cavity, which is separated into left and right sections by the nasal septum. The floor of the nasal cavity is composed of the hard palate and the soft palate. The nasal cavities are lined with mucous membranes that produce mucus, a substance created for lubrication and protection. Rhinorrhea, commonly referred to as a “runny nose,” is a medical term for excess mucus production by the nasal cavities.

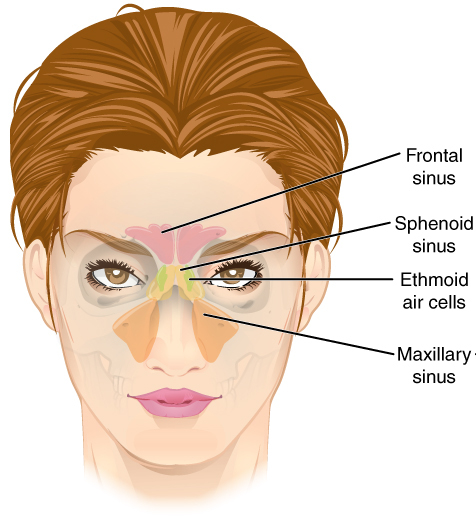

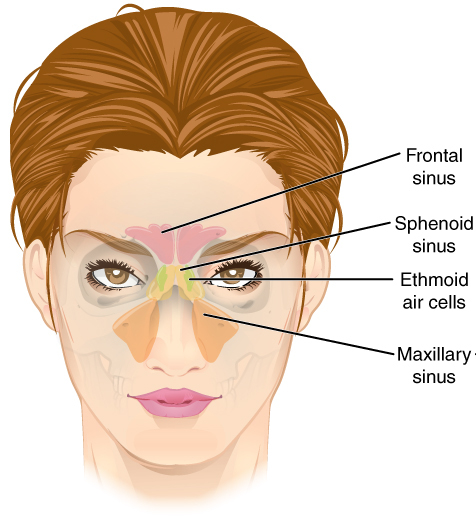

Adjacent to the nasal cavity are the sinuses that serve to warm and humidify incoming air. There are four sinuses named for their adjacent bones: frontal sinus, maxillary sinus, sphenoidal sinus, and ethmoidal sinus. Air moves from the nasal cavities and sinuses into the pharynx. Sinusitis refers to inflammation of the sinus cavities.[3]

Pharynx

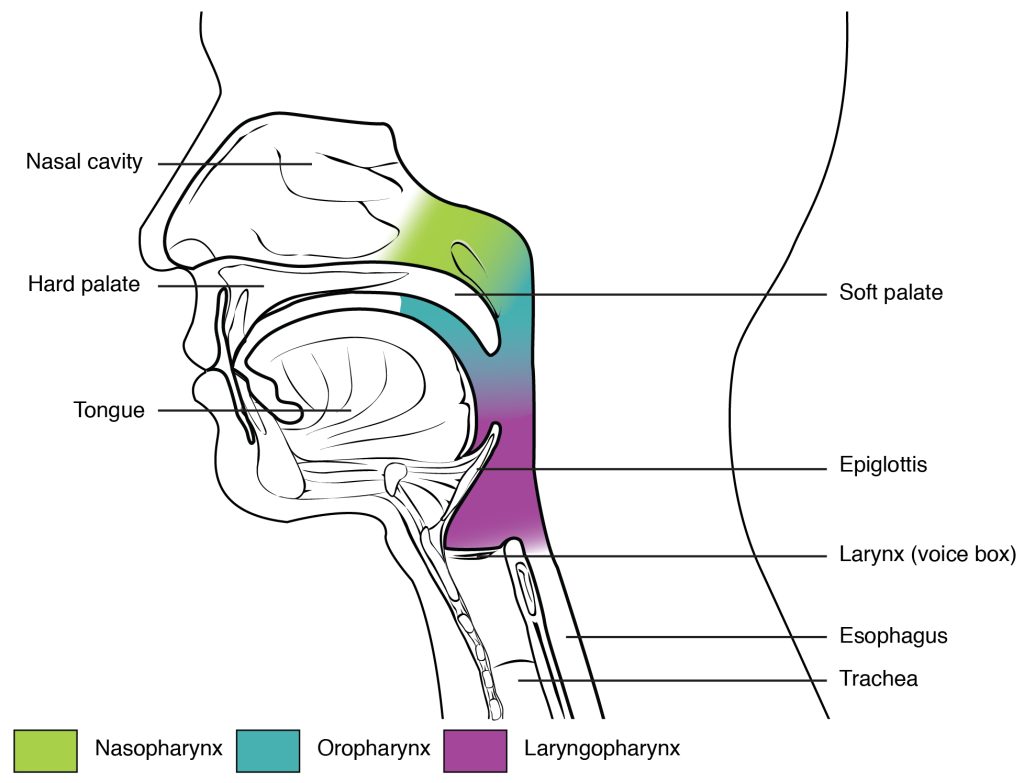

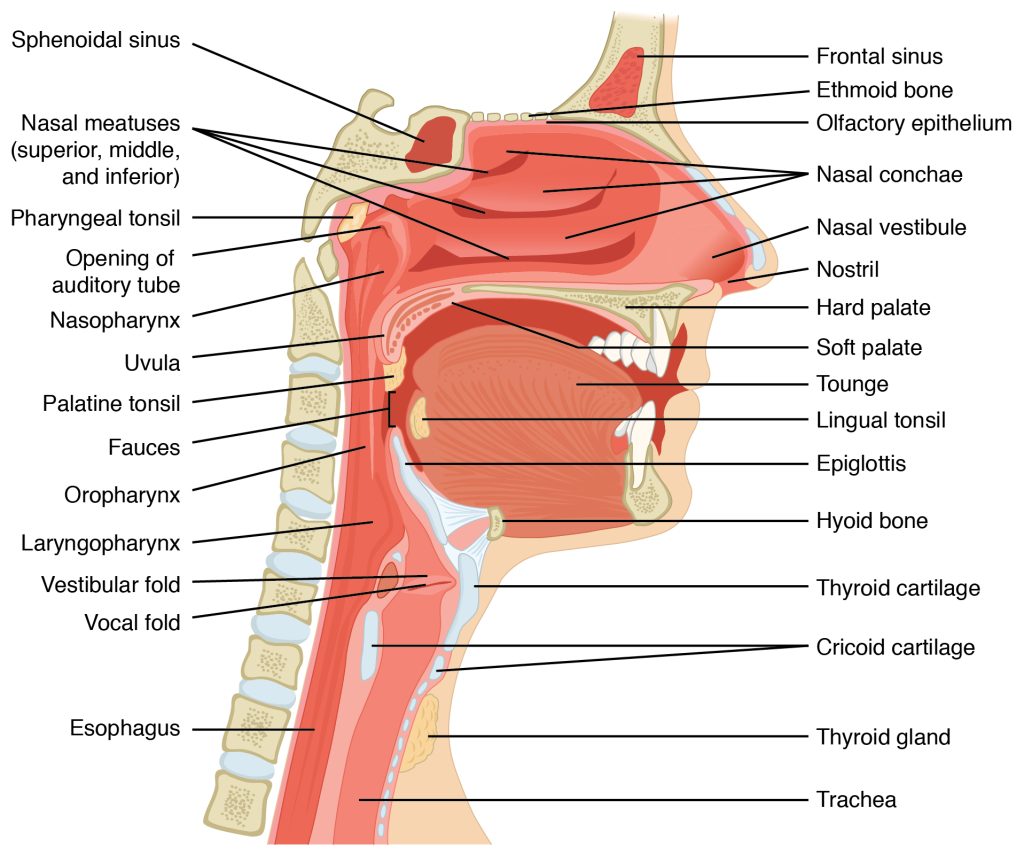

The pharynx, commonly known as the throat, is divided into three major regions: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx. See Figure 6.3[4] for an illustration of the regions of the pharynx.[5]

At the top of the nasopharynx is the pharyngeal tonsil, also called adenoid. The function of the pharyngeal tonsil is to trap and destroy invading pathogens that enter the airway during inhalation. Pharyngitis is inflammation of the pharynx, and tonsillitis is inflammation of the tonsils.[6]

The soft palate and a bulbous structure called the uvula swing upward during swallowing to close off the nasopharynx to prevent ingested materials from entering the nasal cavity. Eustachian tubes connect the middle ear cavities with the nasopharynx. This connection is why upper respiratory infections often lead to ear infections.[7]

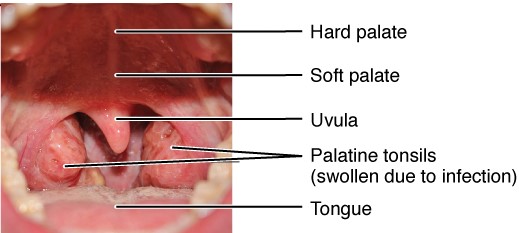

The oropharynx is bordered superiorly by the nasopharynx and anteriorly by the oral cavity. The oropharynx contains two distinct sets of tonsils called the palatine tonsils and lingual tonsils that also trap and destroy pathogens entering the body through the oral or nasal cavities. Adenoids are lymphatic tissue between the back of the nasal cavity and the pharynx. Adenoiditis refers to inflammation of the adenoids, a common medical condition in young children that can hinder speaking and breathing.[8]

The laryngopharynx is just below the oropharynx. It is part of the pharynx (throat) located behind the larynx. The laryngopharynx separates into the trachea (the tube going into the larynx) and the esophagus (the tube going into the stomach). The epiglottis prevents food and fluid from entering the trachea while swallowing.[9]

Larynx

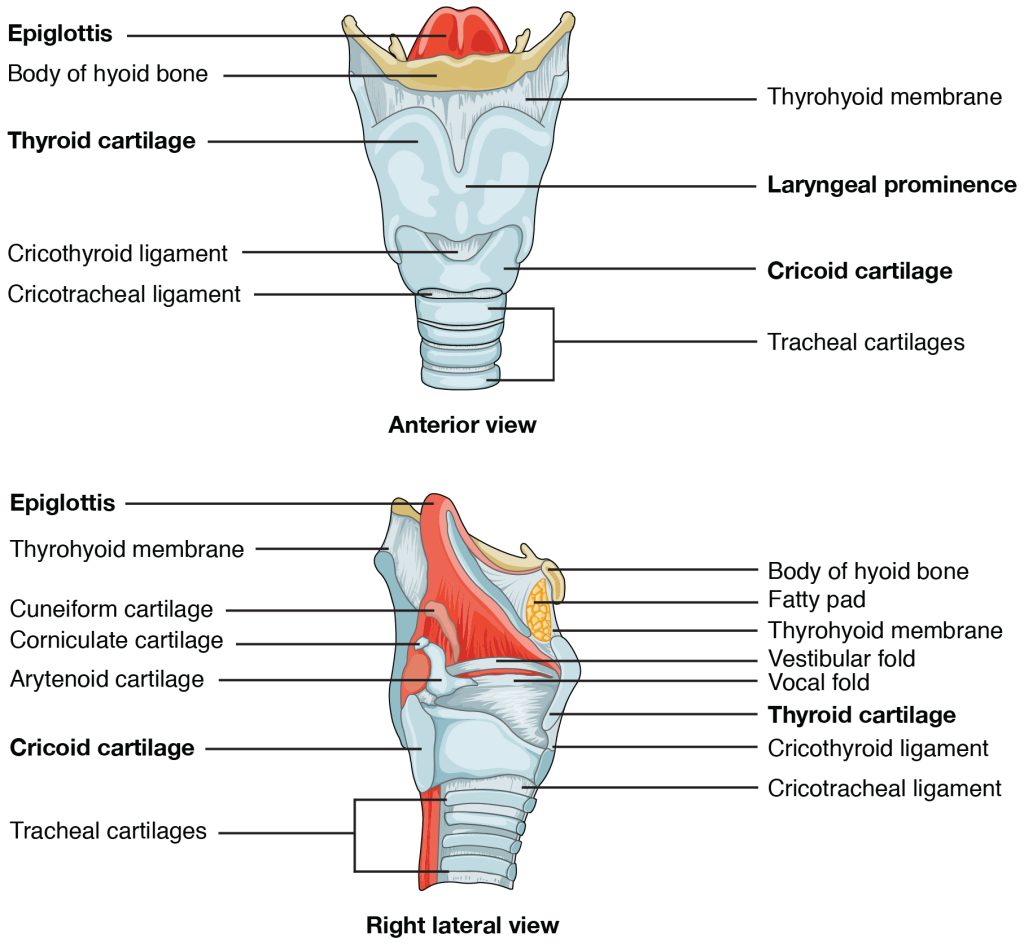

The structure of the larynx is formed by several pieces of cartilage, as shown in Figure 6.4.[10] Three large cartilage pieces form the major structure of the larynx called the thyroid cartilage (the larger piece of cartilage on the anterior side), epiglottis (at the top of the larynx), and cricoid cartilage (just inferior to the thyroid cartilage). Laryngitis refers to inflammation of the larynx, specifically the vocal cords, typically resulting in huskiness or loss of one’s voice and a cough.[11]

The epiglottis is a flap of tissue that covers the trachea during swallowing to prevent aspiration, the inhalation of food or fluids into the trachea and lower respiratory tract. The act of swallowing causes the pharynx and larynx to lift upward, allowing the pharynx to expand and the epiglottis of the larynx to swing downward, closing the opening to the trachea.[12]

Vocal cords are white, membranous folds attached by muscle to the cartilages of the larynx on their outer edges. The inner edges of the vocal cords are free, allowing oscillation as air passes through to produce sound for speaking.[13]

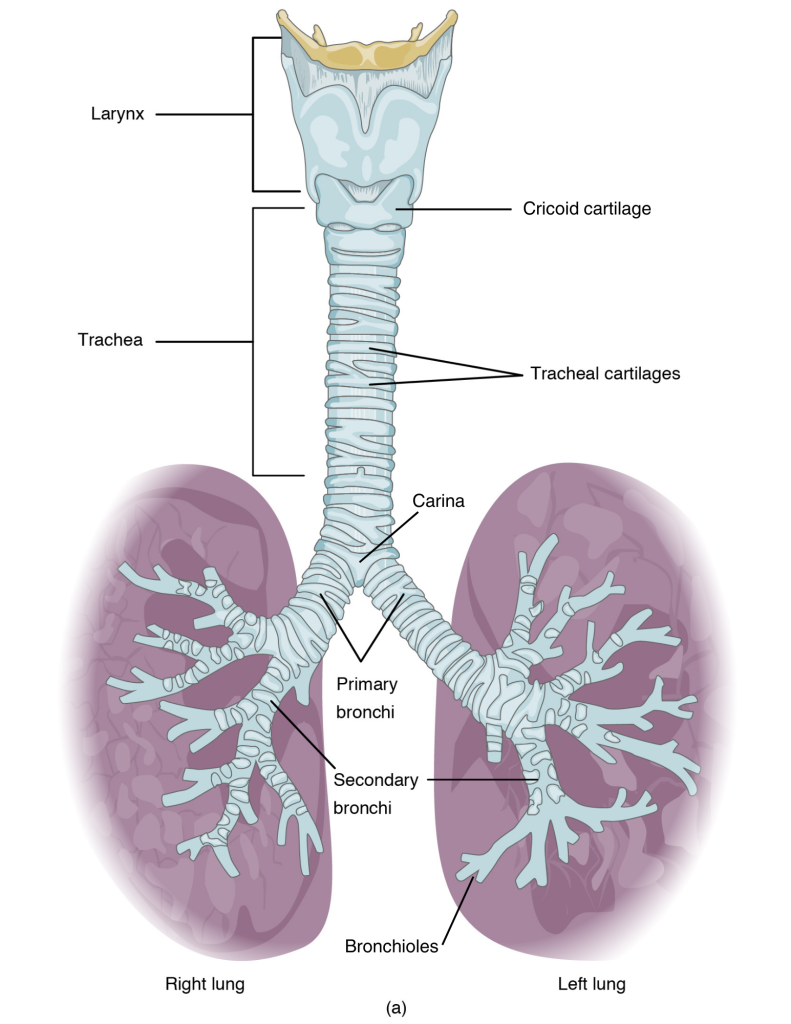

The lower respiratory tract consists of the trachea, bronchi, alveoli, and lungs.[14]

Trachea

The trachea is formed by stacked, C-shaped pieces of cartilage that are connected by dense connective tissue. See Figure 6.5[15] for an illustration of the trachea. The trachea stretches and expands slightly during inhalation and exhalation, whereas the rings of cartilage provide structural support and prevent the trachea from collapsing. The trachea is lined with cilia and mucus-secreting cells to trap debris and move it towards the pharynx to be swallowed or spit out.[16]

If the upper respiratory tract becomes blocked with mucus, inflammation, or a foreign object, no air can pass to the lungs, causing a life-threatening emergency requiring a tracheostomy. A tracheostomy is an incision created in the trachea to create an artificial opening to allow breathing when an obstruction is present.[17]

Bronchi and Bronchioles

Bronchi are the main air passageways of the lungs. The trachea branches into the right and left primary bronchi at the carina. The carina is a raised structure that contains specialized nervous system tissue that induces violent coughing if a foreign body, such as food, is present. Rings of cartilage, similar to those of the trachea, support the structure of the bronchi and prevent their collapse. The bronchi of each lung continue to branch up to 26 times creating the bronchial tree, which looks similar to the branching of an actual tree. The main function of the bronchi is to provide a passageway for air to move into and out of each lung.[18]

Bronchioles are the smallest branches of the bronchi that lead to the alveolar sacs. The muscular walls of these tiny bronchioles do not contain cartilage like those of the bronchi, so the muscular wall can change the size of the bronchioles to increase or decrease airflow to the alveoli. Bronchospasm is a symptom of many respiratory conditions that refers to a sudden constriction of the muscles in the walls of the bronchioles. Bronchitis refers to inflammation of the bronchi.[19]

The trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles are lined with mucous membranes that create mucus secretions that can be expelled through the mouth, also referred to as sputum.[20]

Alveoli

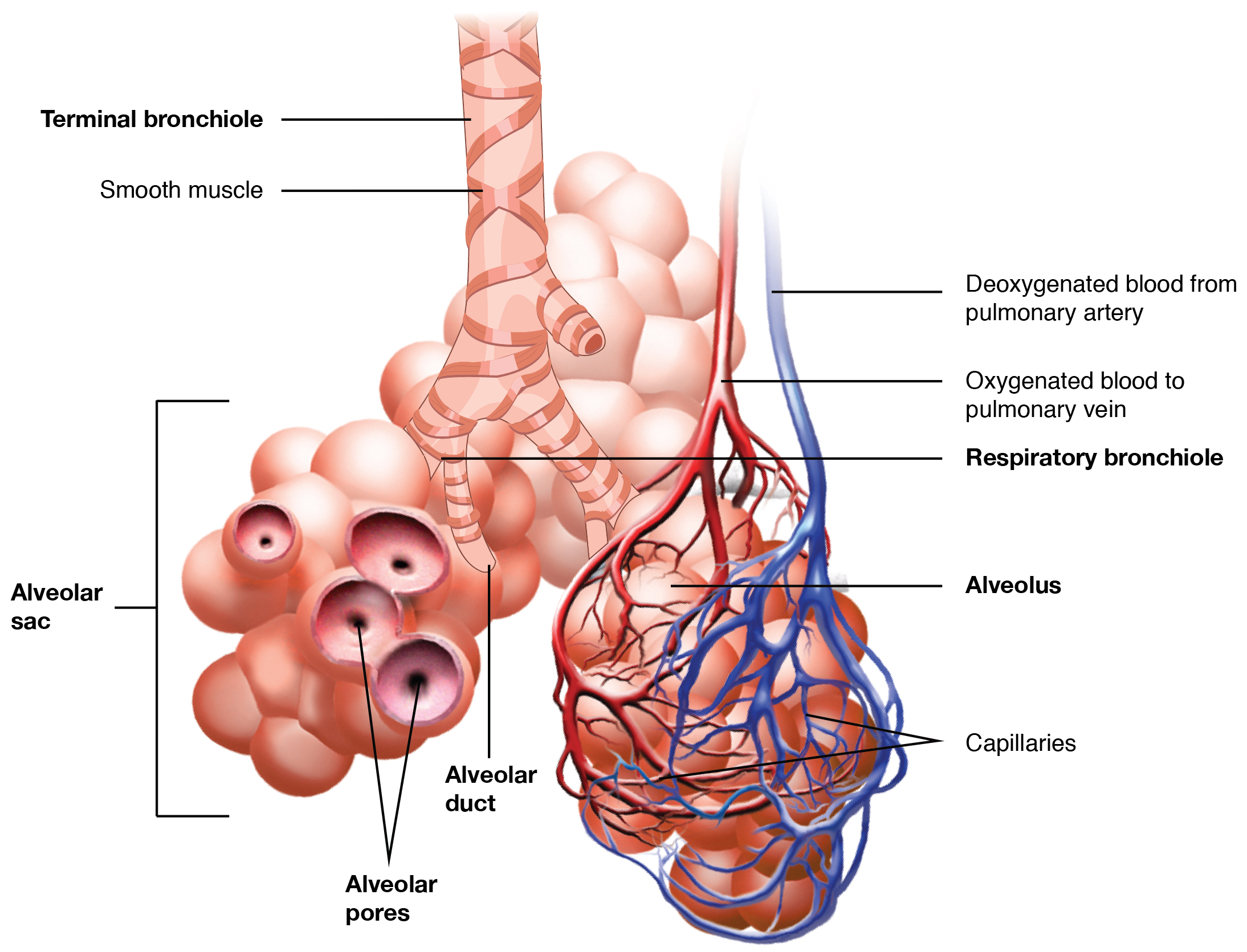

Alveoli are small, grape-like sacs where gas exchange occurs. See Figure 6.6[21] for an illustration of one alveolus surrounded by capillaries. The blue capillaries refer to deoxygenated blood transported to the lungs from the pulmonary artery, and the red capillaries refer to oxygenated blood that is being transported back to the heart via the pulmonary vein. Note in this case that a vein is carrying oxygenated blood. Veins always carry blood back to the heart, but most of the time, it is deoxygenated. However, in this case, the pulmonary vein is transporting blood that is oxygenated back to the heart because it is being transported from the lungs.[22]

Alveoli have elastic walls that allow the alveolus to stretch during air intake, which greatly increases the surface area available for gas exchange. Alveoli secrete surfactant, a slippery substance that keeps the lungs from collapsing. Atelectasis is a medical term that refers to the collapse of alveoli and/or small passageways of the lungs that can result in a partially or completely collapsed lung.[23]

Lungs

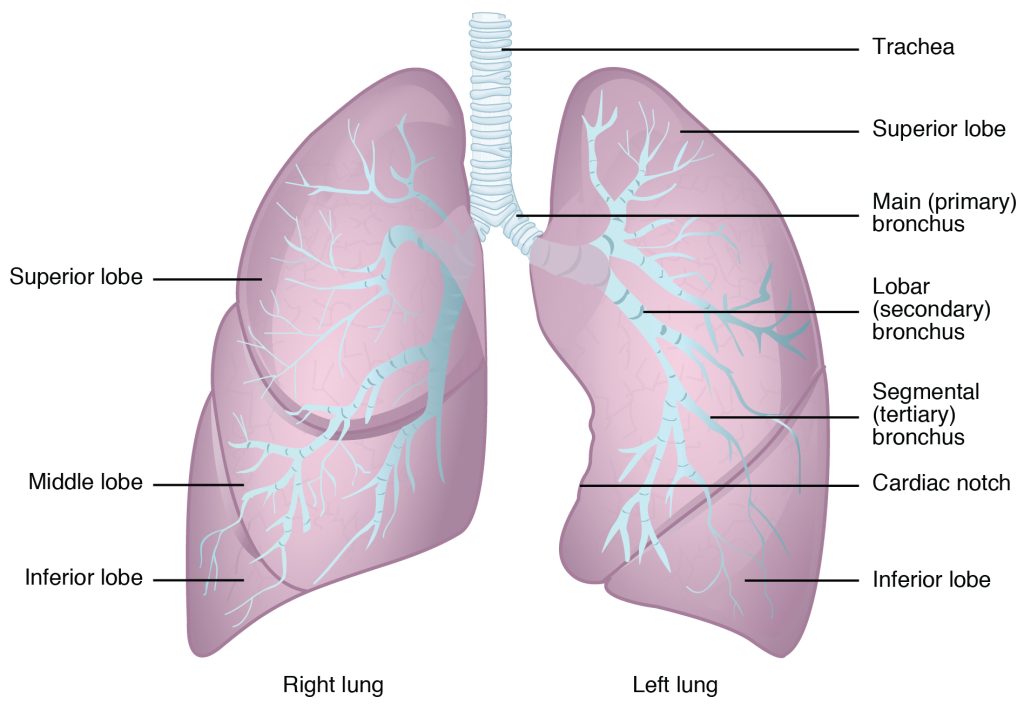

The lungs are connected to the trachea by the main (primary) bronchi that branches into the right and left bronchi. See Figure 6.7[24] for an illustration of the lungs. On the inferior surface, the lungs are bordered by the diaphragm. The cardiac notch, a medial indentation found only on the left lung, allows space for the heart. The apex of the lung is the superior region, whereas the base is the distal region near the diaphragm.[25]

Each lung is composed of smaller units called lobes. The right lung consists of three lobes: the superior, middle, and inferior lobes. The left lung is smaller and only contains two lobes, superior and inferior, as it shares space with the heart. Each lobe receives its own large bronchus that has multiple branches. A lobectomy refers to surgical removal of a lobe of the lung.[26]

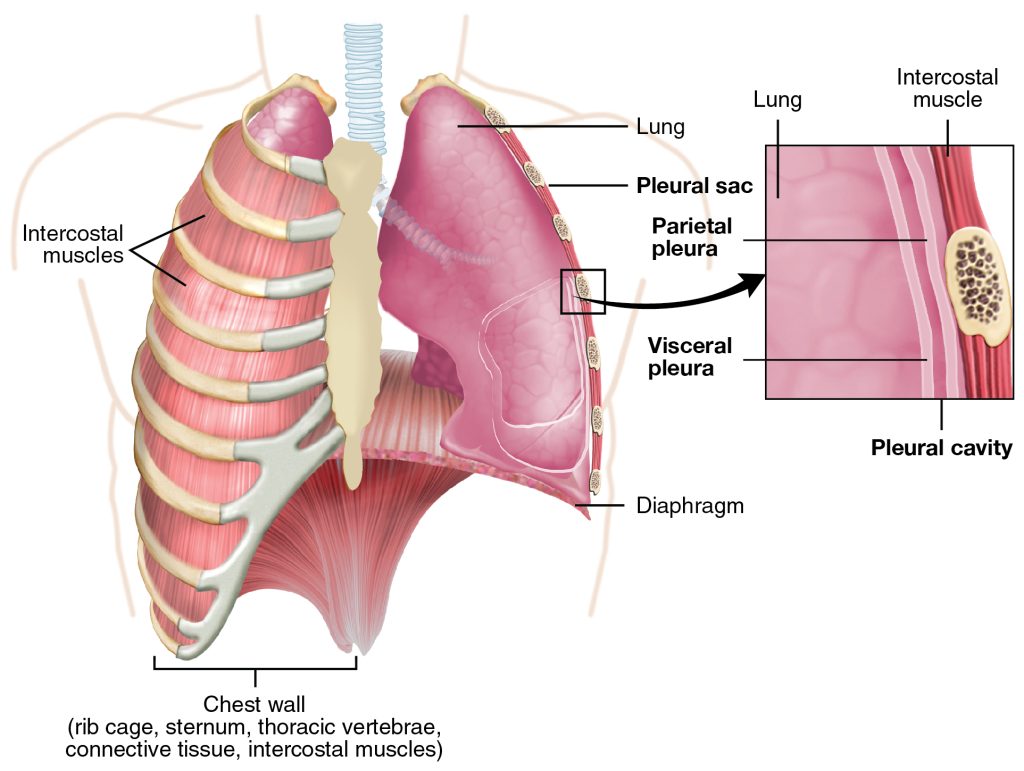

There are two pleural membranes in the lungs. The visceral pleura is a thin membrane on the outer surface of the lungs. The parietal pleura lines the inside of the thoracic cavity. Between these two membranes is the pleural cavity that contains pleural fluid to reduce friction and also sticks to the lungs to help keep them inflated. See Figure 6.8[27] for an illustration of the pleural membranes and the pleural cavity. Pleural effusion refers to excessive fluid between the pleural membranes that is commonly caused by disease or trauma.[28]

The main function of the respiratory system is gas exchange, meaning providing the body with a constant supply of oxygen to the body and removing carbon dioxide. To achieve gas exchange, the structures of the respiratory system create the mechanical movement of air into and out of the lungs called ventilation.[29]

Ventilation and the Mechanics of Breathing

The lungs bring oxygen to the cells of our body through inhalation and exhalation. Inhalation, also called inspiration, is the act of breathing air inward. During inhalation, the diaphragm contracts and flattens, creating a larger lung cavity, which decreases the pressure inside the lungs. At the same time, the intercostal muscles (the muscles between the ribs) pull downward, also causing the thoracic cavity to expand. The thoracic cavity is the space inside the chest that contains the heart, lungs, and other organs. As the thoracic cavity expands, a negative pressure (i.e., vacuum) is created inside the chest cavity, causing air to rush into the lungs (because air always moves from high pressure to low pressure).[30]

During exhalation, also called expiration or the act of breathing out, the diaphragm relaxes and the thoracic cavity springs back to its original position. This causes the volume of the thoracic cavity to decrease and pressure to increase, causing air to leave the lungs.

Lung sounds are caused by the movement of air from the trachea to the bronchioles to the alveoli and can be impacted by the presence of sputum, bronchoconstriction, or fluid in the alveoli. These sounds are referred to as rhonchi (coarse crackles), rales (fine crackles), wheezes, stridor, and pleural rub[31]:

- Rhonchi, also referred to as coarse crackles, are low-pitched, continuous sounds heard on expiration that are a sign of turbulent airflow through mucus in the large airways.

- Rales, also called fine crackles, are popping or crackling sounds heard on inspiration. They are associated with medical conditions that cause fluid accumulation within the alveolar and interstitial spaces, such as heart failure or pneumonia. The sound is similar to that produced by rubbing strands of hair together close to your ear.

- Wheezes are whistling noises produced when air is forced through airways narrowed by bronchoconstriction or mucosal edema. For example, clients with asthma commonly have wheezing.

- Stridor is heard only on inspiration. It is associated with obstruction of the trachea/upper airway.

- Pleural rub sounds like the rubbing together of leather and can be heard on inspiration and expiration. It is caused by inflammation of the pleura membranes that results in friction as the surfaces rub against each other.

Listen to lungs sounds in the “Respiratory Assessment” section of the “Respiratory Assessment” chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Forced breathing is a type of breathing that can occur during exercise, singing, or playing a musical instrument. During forced breathing, inspiration and expiration both occur due to muscle contractions. In addition to the contraction of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, other accessory muscles must also contract. Muscles of the neck contract and lift the thoracic wall, increasing lung volume, and accessory muscles of the abdomen contract, forcing abdominal organs upward against the diaphragm. This helps to push the diaphragm farther into the thorax, pushing out more air. In addition, accessory muscles help to compress the rib cage, which also reduces the volume of the thoracic cavity. These additional muscle contractions during inspiration also occur during labored breathing, a symptom of many respiratory disorders.[32]

Control of Breathing

Respiratory rate is the number of breaths taken per minute. The normal respiratory rate for adults is 12-20 breaths per minute. A child under 1 year of age has a normal respiratory rate between 30 and 60 breaths per minute. By the time a child is about eleven years old, the normal rate is closer to 14 to 22.

Respiratory rate may increase or decrease during illness or disease. Medical terms related to breathing include tachypnea (rapid breathing), bradypnea (slow breathing), and apnea (episodes of the absence of breathing). Dyspnea is a common symptom of respiratory disorders and refers to shortness of breath or a feeling of breathlessness.[33]

The respiratory rate is controlled by the respiratory center located within the medulla oblongata and pons in the brain stem, which responds primarily to changes in carbon dioxide, oxygen, and pH levels in the blood. These changes are sensed by central chemoreceptors, which are located in the brain, and peripheral chemoreceptors, which are located in the aortic arch and carotid arteries.

The major factor that drives breathing is not hypoxemia (a decreased amount of dissolved oxygen in the blood), but rather the concentration of carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is a waste product of cellular respiration and is toxic at high levels in the blood. Elevated levels of carbon dioxide are called hypercapnia. As carbon dioxide levels increase, the central chemoreceptors stimulate the contraction of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, increasing the rate and depth of respirations to help rid the body of carbon dioxide. Hyperventilation refers to rapid and deep breathing. It can occur for many reasons such as anxiety and pain, but it can also be a sign the body is trying to compensate for acidosis and increasing the pH level by eliminating excess carbon dioxide.

In contrast, low levels of carbon dioxide in the blood stimulate shallow, slow breathing to help the body retain carbon dioxide. Hypoventilation refers to slow and shallow breathing.[34] Hypoventilation can occur for several reasons, such as oversedation by opioids and exhaustion from hyperventilation. It can also be a sign the body is trying to compensate for alkalosis by retaining carbon dioxide and decreasing the pH level.

Gas Exchange

Ventilation (i.e., the mechanics of breathing) provides air to the alveoli for gas exchange. Respiration refers to the exchange of gases in the lungs between the alveoli and the pulmonary capillaries or in the tissues between the systemic capillaries and cells/tissues.

Gas exchange refers to the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide through capillary walls of the alveoli and the pulmonary capillaries, called external respiration. During external respiration, oxygen from the air we breathe diffuses into the blood. Carbon dioxide (waste) diffuses out of the blood and into the alveoli where it can be exhaled. Throughout the rest of the body, gas exchange also occurs between the systemic capillaries and body cells/tissues, called internal respiration. During internal respiration, oxygen diffuses out of the systemic capillaries and body cells/tissues, and carbon dioxide diffuses from the cells/tissues into the systemic capillaries where it is carried to the lungs. It is through this process that cells in the body are oxygenated and carbon dioxide, the waste product of cellular respiration, is removed from the body.[35]

Perfusion

In addition to adequate ventilation, the second important aspect of gas exchange is perfusion. Perfusion refers to the flow of blood. In the lungs, perfusion occurs in the pulmonary circulation as it moves from the heart into the lungs and then back to the heart for distribution to the body. The pulmonary arteries carry deoxygenated blood from the heart into the lungs, where they branch and eventually become the capillary network composed of pulmonary capillaries. These pulmonary capillaries create the respiratory membrane with the alveoli. As the blood is pumped through this capillary network, gas exchange occurs.[36]

Although a small amount of the oxygen is able to dissolve directly into the blood from the alveoli, most of the oxygen binds to hemoglobin within the red blood cells. The more oxygen the hemoglobin in the red blood cells carry, the brighter red the color of the blood. Oxygenated blood returns to the heart through the pulmonary veins to the left atrium and ventricle, where it is pumped out to the body via the aorta. The hemoglobin on the red blood cells transports the oxygen to the tissues throughout the body.[37]

Hypoxia and Hypoxemia

Diseases and disorders affecting the respiratory system can cause hypoxia, defined as reduced tissue oxygenation. Hypoxia can occur due to inadequate ventilation or impaired perfusion, also referred to as V-Q mismatch, where the ratio of air ventilating the lungs’ alveoli (V) to blood perfusing through the surrounding capillaries (Q) is not properly matched.

Pulmonary edema is an example of hypoxia caused by inadequate ventilation due to fluid accumulation in alveoli, often caused by heart failure or kidney failure. As a result of the fluid accumulation, oxygen cannot move across the alveolar membrane into the blood, and carbon dioxide cannot be removed from the blood. As a result, hypoxia and hypercapnia (high levels of carbon dioxide) may occur, requiring urgent medical interventions to sustain life by decreasing carbon dioxide levels and increasing oxygen levels.[38]

Another example of hypoxia caused by impaired perfusion is a pulmonary embolism. Let’s take a closer look at pulmonary embolism in the box below.

Pulmonary Embolism

A pulmonary embolism (PE) can occur when a clot from elsewhere in the body travels through venous circulation and gets lodged in the blood vessels of the lungs. This impedes blood flow, and impacted lung tissue dies. PEs are medical emergencies that require emergent treatment. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism involves various tests:

- CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA): Visualizes blood flow in the pulmonary arteries.

- D-dimer test: Detects the presence of a substance that may indicate the presence of a blood clot.

- Ultrasound: Checks for DVT in the legs.

- Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan: Detects blood flow and air movement in the lungs.

Signs and symptoms of PE include sudden shortness of breath, sudden anxiety or feeling of “impending doom,” chest pain, rapid heart rate, coughing up blood, sweating, feeling lightheaded or dizzy, or leg swelling or pain if a DVT is present. Read more about DVT in the “Cardiovascular Alterations” chapter. Complications of PE include death of lung tissue, increased pulmonary pressure in the arteries of the lungs, and cardiac arrest. Rapid intervention is required if PE is suspected. Treatment includes blood thinners to prevent additional clotting, thrombolytic therapy to dissolve clots, inferior vena cava (IVC) filter to prevent clots traveling to the lungs, oxygen therapy, and supportive measures such as pain management and breathing exercises.[39]

The term hypoxia and hypoxemia are not synonymous. Whereas hypoxia refers to reduced tissue oxygenation, hypoxemia is defined as a decrease in the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PaO2). Hypoxemia can be caused by impaired delivery of oxygen to the tissues or defective utilization of oxygen by tissues. Additionally, hypoxemia and hypoxia do not always coexist. For example, clients can develop hypoxemia without hypoxia if there is a compensatory increase in their hemoglobin levels and/or cardiac output (CO).[40]

Media Attributions

- 2301_Major_Respiratory_Organs

- Blausen_0872_UpperRespiratorySystem

- 2305_Divisions_of_the_Pharynx

- 2306_The_Larynx

- Trachea

- 2309_The_Respiratory_Zone

- 2312_Gross_Anatomy_of_the_Lungs

- 2313_The_Lung_Pleurea

- “2301_Major_Respiratory_Organs.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Blausen_0872_UpperRespiratorySystem.png” by Blausen.com staff (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014 is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "2305_Divisions_of_the_Pharynx.jpg" by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2306_The_Larynx.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Trachea” by Meredith Pomietlo is a derivative of "File:2308a_The Trachea" by OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2309_The_Respiratory_Zone” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “2312_Gross_Anatomy_of_the_Lungs.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "2313_The_Lung_Pleurea.jpg" by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Open RN Nursing Skills 2e by Chippewa Valley Technical College with CC BY 4.0 licensing. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medical Terminology - 2e by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, June 28). Venous thromboembolism. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/facts.html ↵

- Sarkar, M., Niranjan, N., & Banyal, P. K. (2017). Mechanisms of hypoxemia. Lung India, 34(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-2113.197116 ↵

Learning Objectives

- Perform a head and neck assessment, including the skull, face, nose, oral cavity, and neck

- Modify assessment techniques to reflect variations across the life span

- Recognize and report significant deviations from norms

- Document actions and observations

Inspection of a patient’s head, neck, and oral cavity is part of the routine daily assessment performed by a registered nurse (RN) during inpatient care.[1] There are also several head and neck conditions that the RN may be the first to notice after a patient is admitted that require notification of the health care provider. Let’s get started by reviewing the basic anatomy and physiology of the head and neck and common medical conditions.

To perform and document an accurate assessment of the head and neck, it is important to understand their basic anatomy and physiology.

Anatomy

Skull

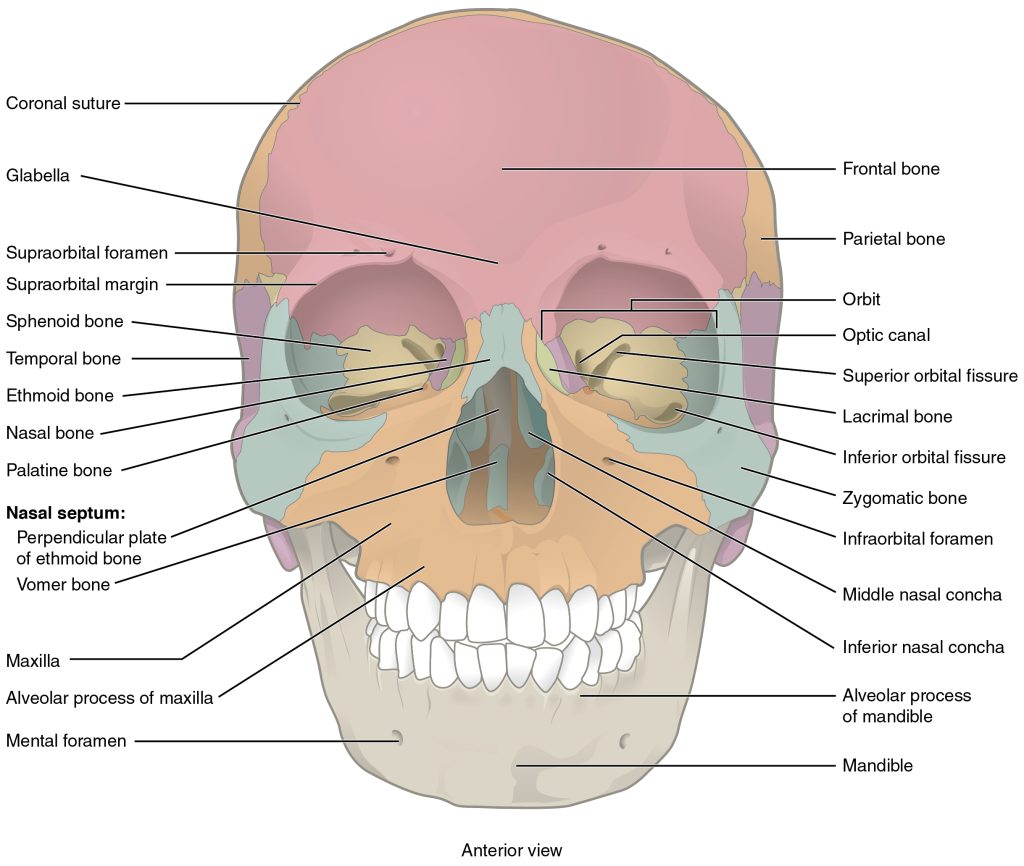

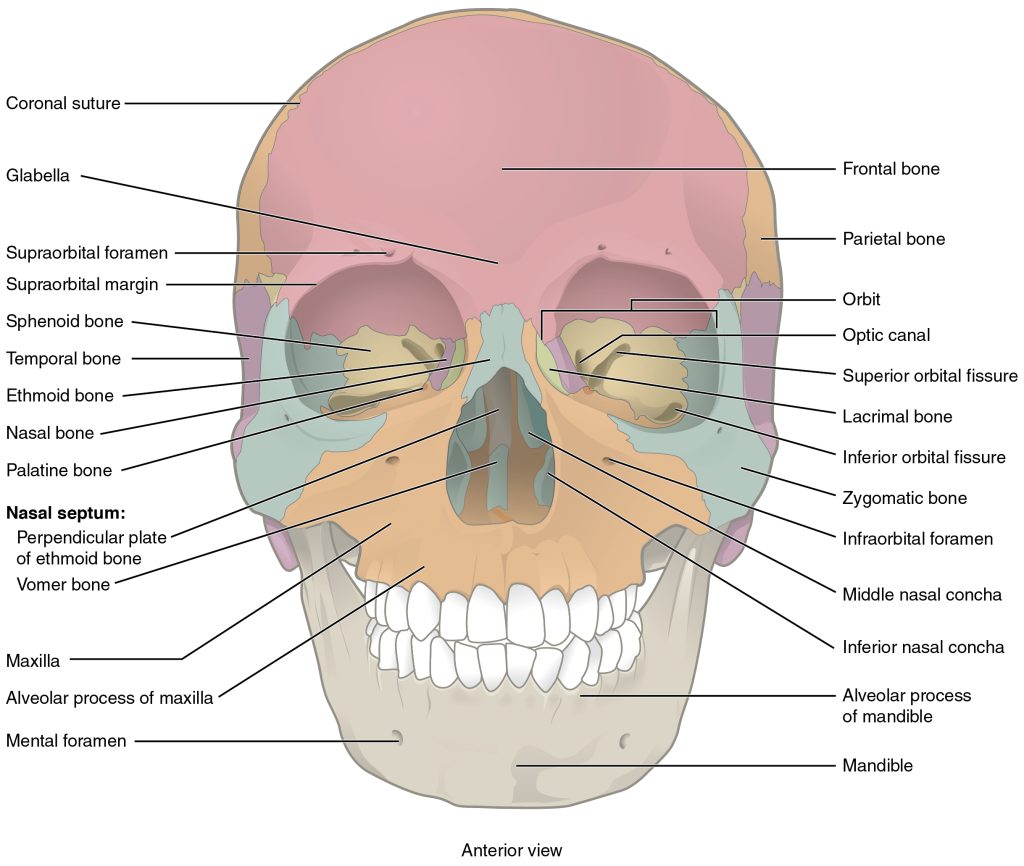

The anterior skull consists of facial bones that provide the bony support for the eyes and structures of the face. This anterior view of the skull is dominated by the openings of the orbits, the nasal cavity, and the upper and lower jaws. See Figure 7.1[2] for an illustration of the skull. The orbit is the bony socket that houses the eyeball and the muscles that move the eyeball. Inside the nasal area of the skull, the nasal cavity is divided into halves by the nasal septum that consists of both bone and cartilage components. The mandible forms the lower jaw and is the only movable bone in the skull. The maxilla forms the upper jaw and supports the upper teeth.[3]

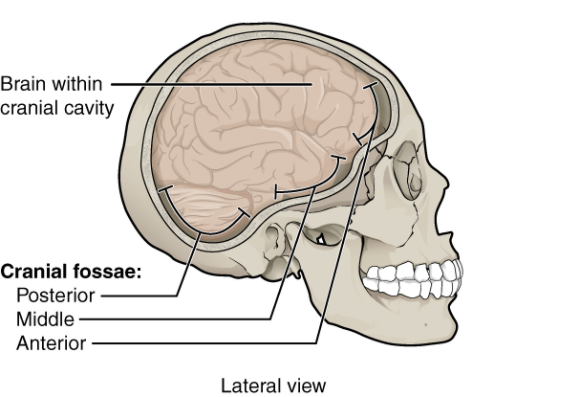

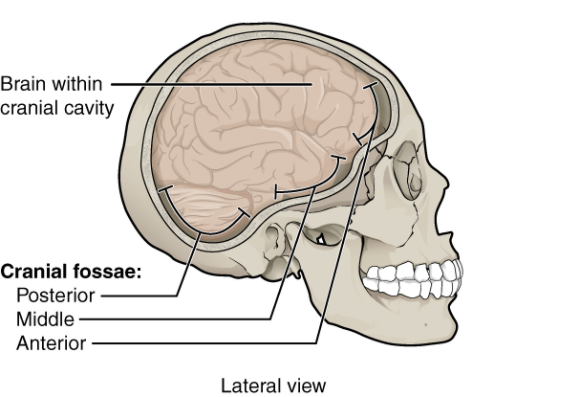

The cranium, or "brain case," surrounds and protects the brain that occupies the cranial cavity. See Figure 7.2[4] for an image of the brain within the cranial cavity. The brain case consists of eight bones, including the paired parietal and temporal bones, plus the unpaired frontal, occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid bones.[5]

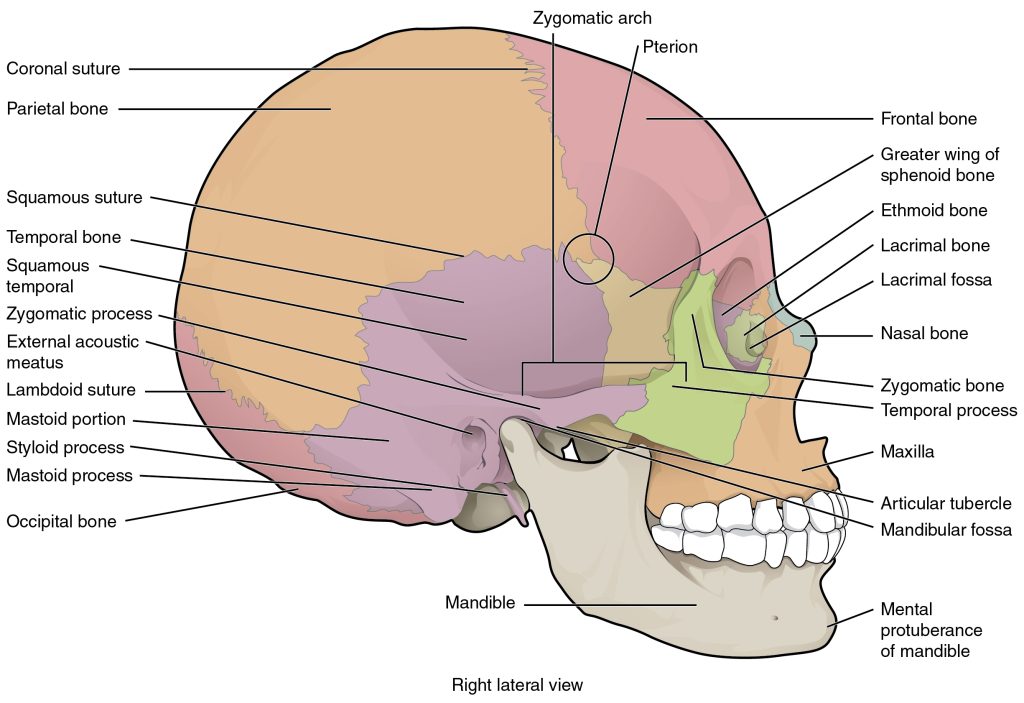

A suture is an interlocking joint between adjacent bones of the skull and is filled with dense, fibrous connective tissue that unites the bones. In a newborn infant, the pressure from vaginal delivery compresses the head and causes the bony plates to overlap at the sutures, creating a small ridge. Over the next few days, the head expands, the overlapping disappears, and the edges of the bony plates meet edge to edge. This is the normal position for the remainder of the life span and the sutures become immobile.

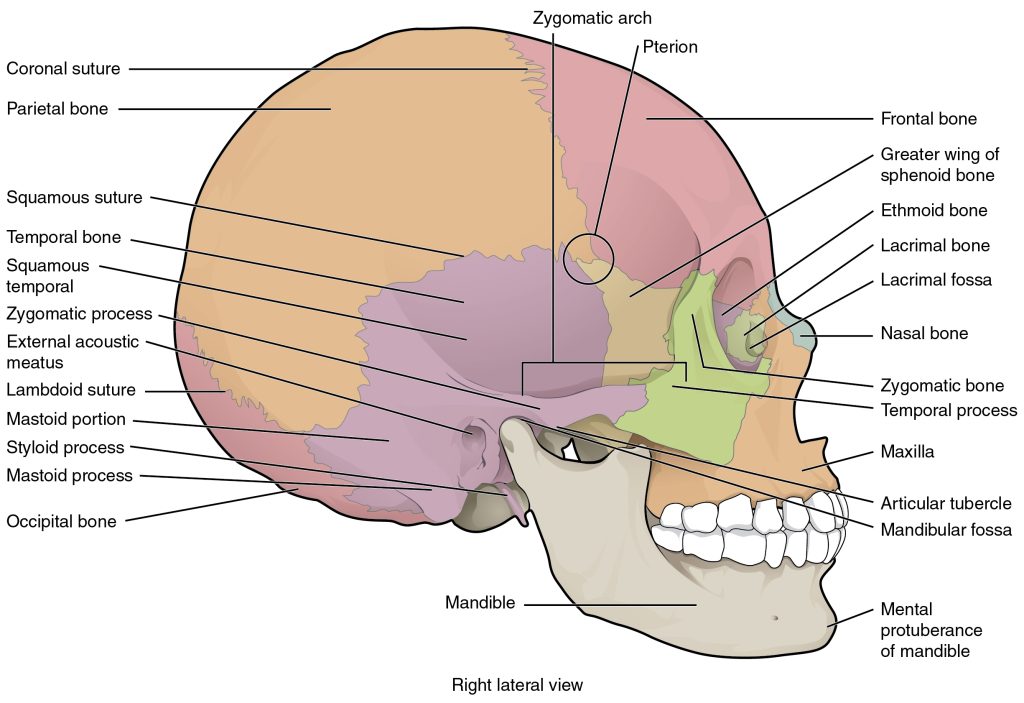

See Figure 7.3[6] for an illustration of two of the sutures, the coronal and squamous sutures, on the lateral view of the head. The coronal suture is seen on the top of the skull. It runs from side to side across the skull and joins the frontal bone to the right and left parietal bones. The squamous suture is located on the lateral side of the skull. It unites the squamous portion of the temporal bone with the parietal bone. At the intersection of the coronal and squamous sutures is the pterion, a small, capital H-shaped suture line region that unites the frontal bone, parietal bone, temporal bone, and greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The pterion is an important clinical landmark because located immediately under it, inside the skull, is a major branch of an artery that supplies the brain. A strong blow to this region can fracture the bones around the pterion. If the underlying artery is damaged, bleeding can cause the formation of a collection of blood, called a hematoma, between the brain and interior of the skull, which can be life-threatening.[7]

Paranasal Sinuses

The paranasal sinuses are hollow, air-filled spaces located within the skull. See Figure 7.4[8] for an illustration of the sinuses. The sinuses connect with the nasal cavity and are lined with nasal mucosa. They reduce bone mass, lightening the skull, and also add resonance to the voice. When a person has a cold or sinus congestion, the mucosa swells and produces excess mucus that often obstructs the narrow passageways between the sinuses and the nasal cavity. The resulting pressure produces pain and discomfort.[9]

Each of the paranasal sinuses is named for the skull bone that it occupies. The frontal sinus is located just above the eyebrows within the frontal bone. The largest sinus, the maxillary sinus, is paired and located within the right and left maxillary bones just below the orbits. The maxillary sinuses are most commonly involved during sinus infections. The sphenoid sinus is a single, midline sinus located within the body of the sphenoid bone. The lateral aspects of the ethmoid bone contain multiple small spaces separated by very thin, bony walls. Each of these spaces is called an ethmoid air cell.

Anatomy of Nose, Pharynx, and Mouth

See Figure 7.5[10] to review the anatomy of the head and neck. The major entrance and exit for the respiratory system is through the nose. The bridge of the nose consists of bone, but the protruding portion of the nose is composed of cartilage. The nares are the nostril openings that open into the nasal cavity and are separated into left and right sections by the nasal septum. The floor of the nasal cavity is composed of the palate. The hard palate is located at the anterior region of the nasal cavity and is composed of bone. The soft palate is located at the posterior portion of the nasal cavity and consists of muscle tissue. The uvula is a small, teardrop-shaped structure located at the apex of the soft palate. Both the uvula and soft palate move like a pendulum during swallowing, swinging upward to close off the nasopharynx and prevent ingested materials from entering the nasal cavity.[11]

As air is inhaled through the nose, the paranasal sinuses warm and humidify the incoming air as it moves into the pharynx. The pharynx is a tube-lined mucous membrane that begins at the nasal cavity and is divided into three major regions: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx.[12]

The nasopharynx serves only as an airway. At the top of the nasopharynx is the pharyngeal tonsil, commonly referred to as the adenoids. Adenoids are lymphoid tissue that trap and destroy invading pathogens that enter during inhalation. They are large in children but tend to regress with age and may even disappear.[13]

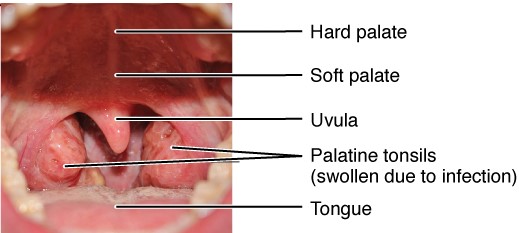

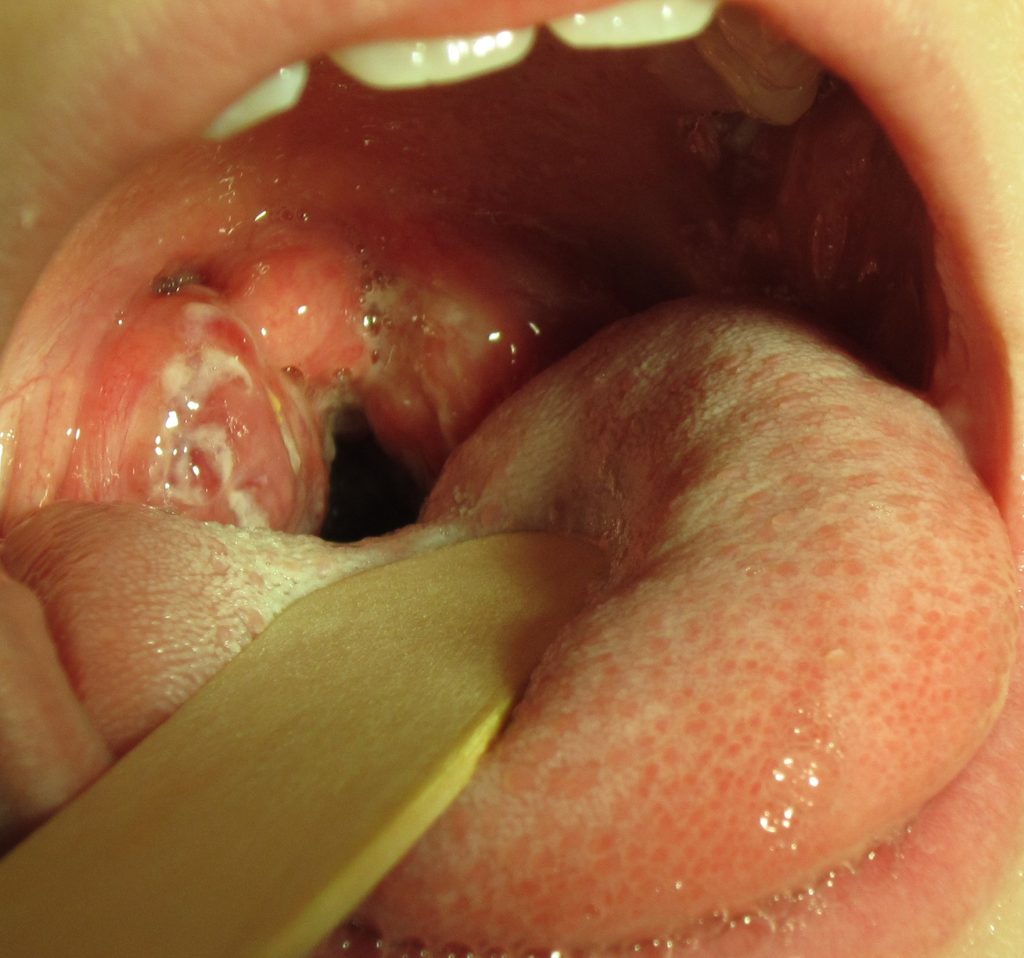

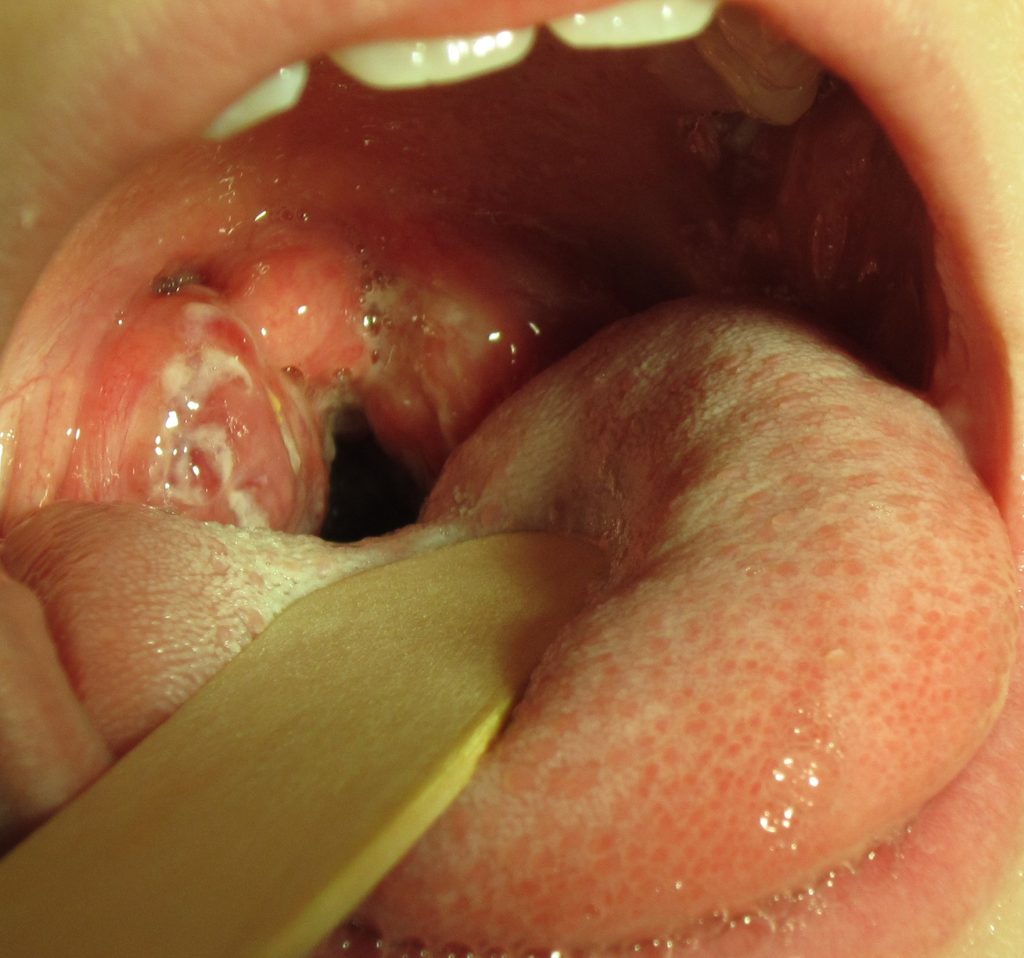

The oropharynx is a passageway for both air and food. The oropharynx is bordered superiorly by the nasopharynx and anteriorly by the oral cavity. The oropharynx contains two sets of tonsils, the palatine and lingual tonsils. The palatine tonsil is located laterally in the oropharynx, and the lingual tonsil is located at the base of the tongue. Similar to the pharyngeal tonsil, the palatine and lingual tonsils are composed of lymphoid tissue and trap and destroy pathogens entering the body through the oral or nasal cavities. See Figure 7.6[14] for an image of the oral cavity and oropharynx with enlarged palatine tonsils.

The laryngopharynx is inferior to the oropharynx and posterior to the larynx. It continues the route for ingested material and air until its inferior end where the digestive and respiratory systems diverge. Anteriorly, the laryngopharynx opens into the larynx, and posteriorly, it enters the esophagus that leads to the stomach. The larynx connects the pharynx to the trachea and helps regulate the volume of air that enters and leaves the lungs. It also contains the vocal cords that vibrate as air passes over them to produce the sound of a person’s voice. The trachea extends from the larynx to the lungs. The epiglottis is a flexible piece of cartilage that covers the opening of the trachea during swallowing to prevent ingested material from entering the trachea.[15]

Muscles and Nerves of the Head and Neck

Facial Muscles

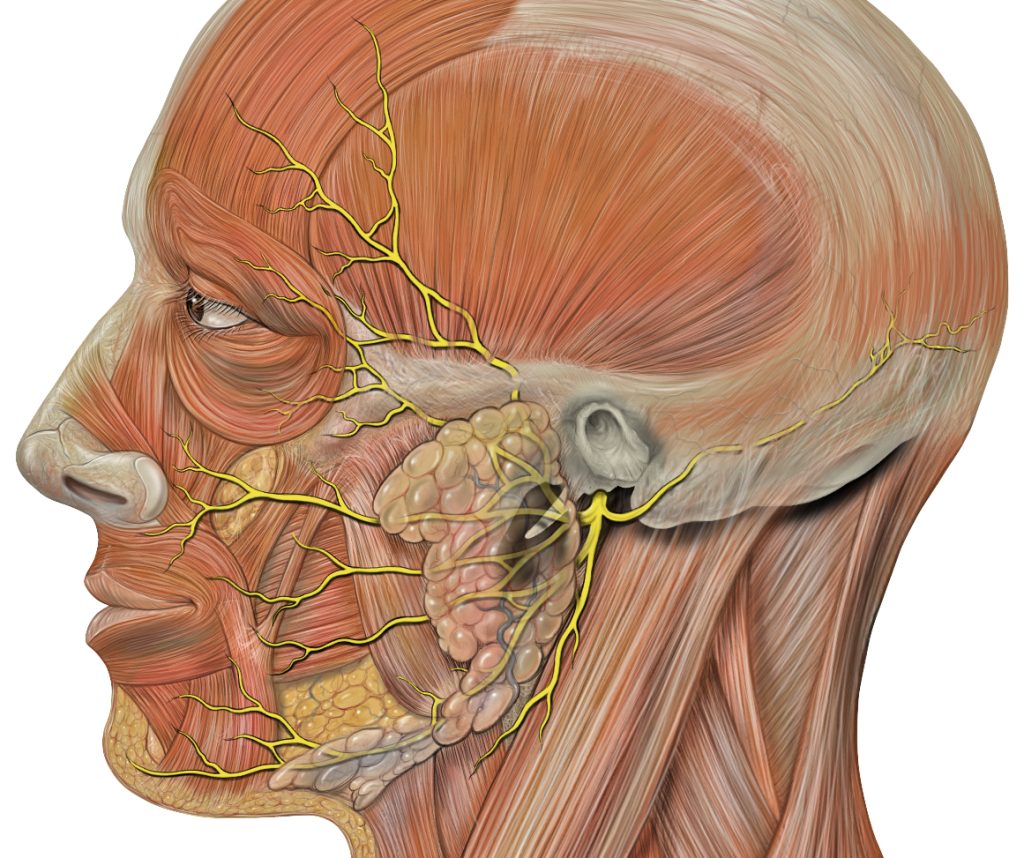

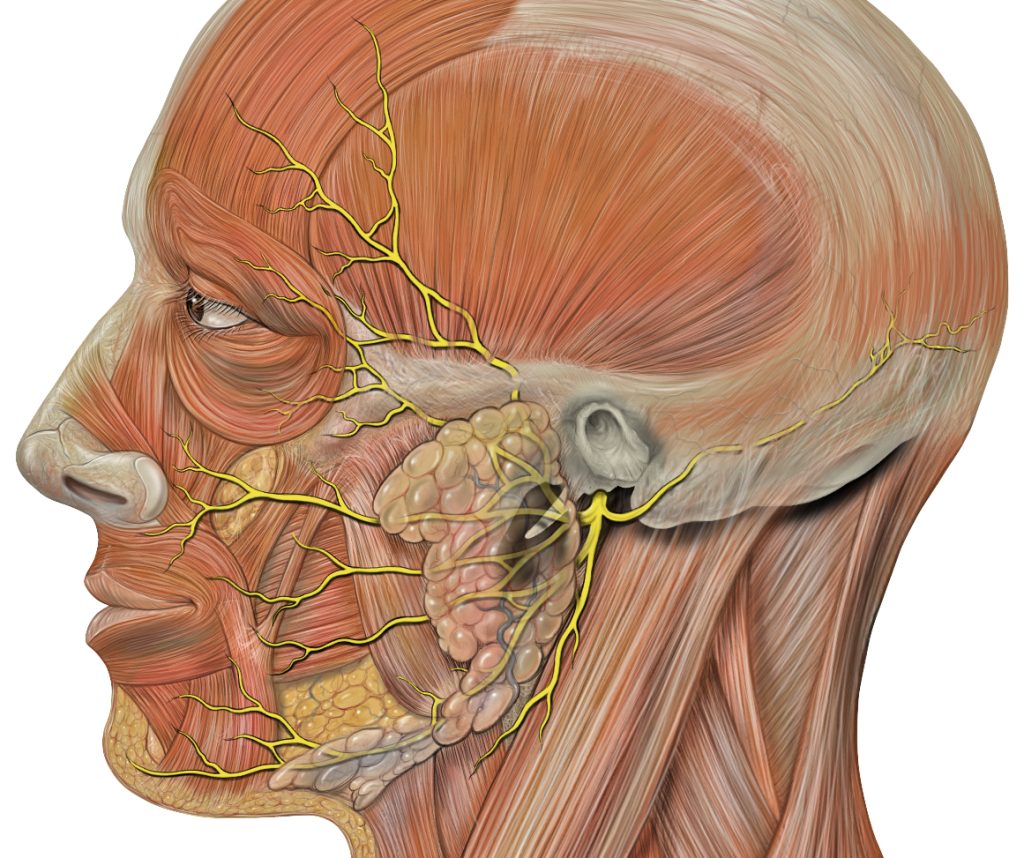

Several nerves innervate the facial muscles to create facial expressions. See Figure 7.7[16] for an illustration of nerves innervating facial muscles. These nerves and muscles are tested during a cranial nerve exam. See more information about performing a cranial nerve exam in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

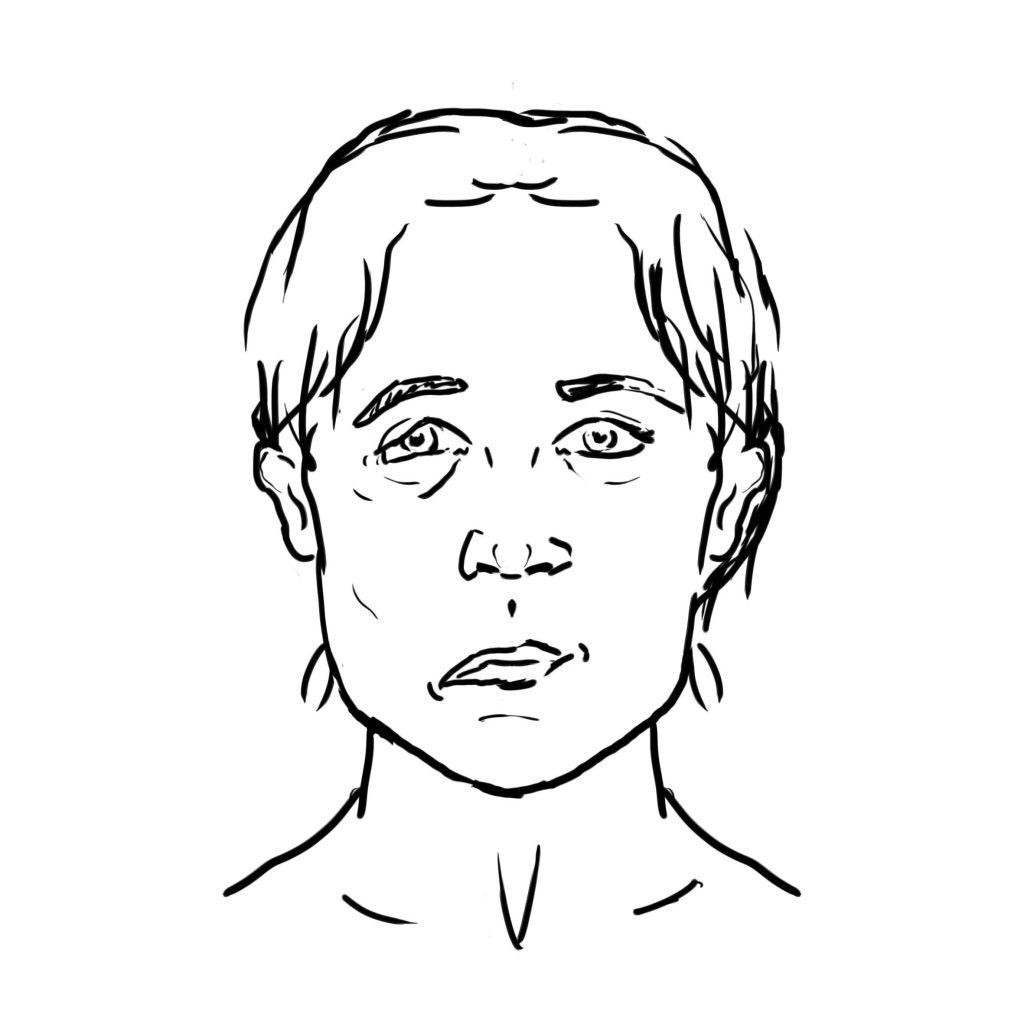

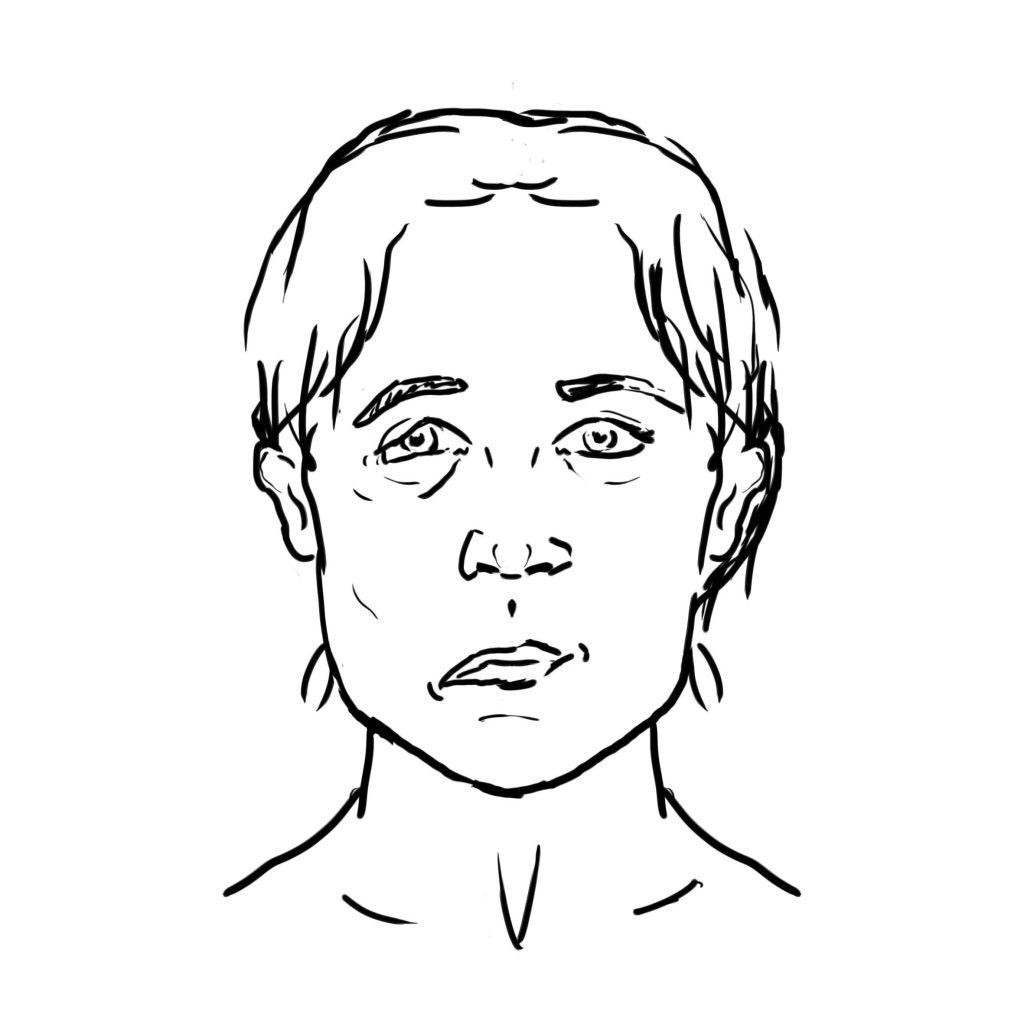

When a patient is experiencing a cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke), it is common for facial drooping to occur. Facial drooping is an asymmetrical facial expression that occurs due to damage of the nerve innervating a specific part of the face. See Figure 7.8[17] for an image of facial drooping occurring on the patient’s right side of their face.

Neck Muscles

The muscles of the anterior neck assist in swallowing and speech by controlling the positions of the larynx and the hyoid bone, a horseshoe-shaped bone that functions as a solid foundation on which the tongue can move. The head, attached to the top of the vertebral column, is balanced, moved, and rotated by the neck muscles. When these muscles act unilaterally, the head rotates. When they contract bilaterally, the head flexes or extends. The major muscle that laterally flexes and rotates the head is the sternocleidomastoid. The trapezius muscle elevates the shoulders (shrugging), pulls the shoulder blades together, and tilts the head backwards. See Figure 7.9[18] for an illustration of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.[19] Both of these muscles are tested during a cranial nerve assessment. See more information about cranial nerve assessment in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

Jaw Muscles

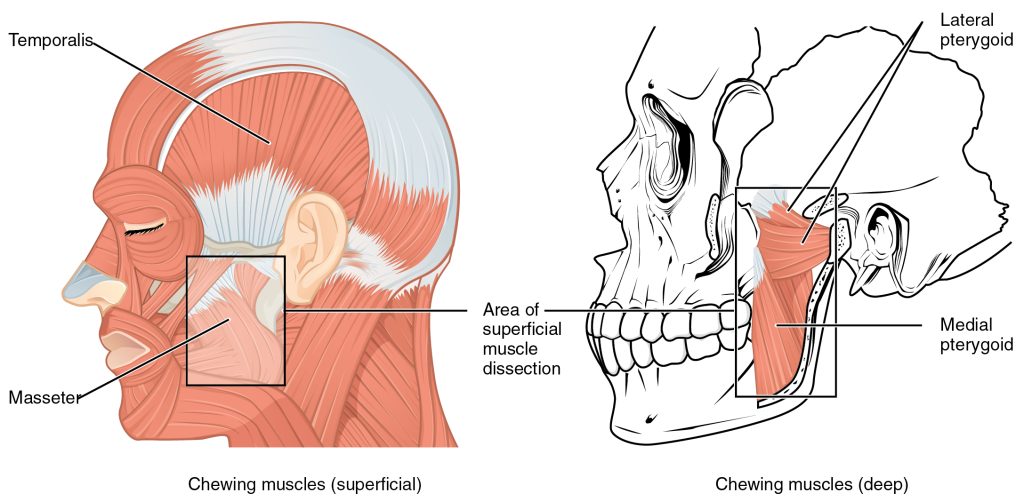

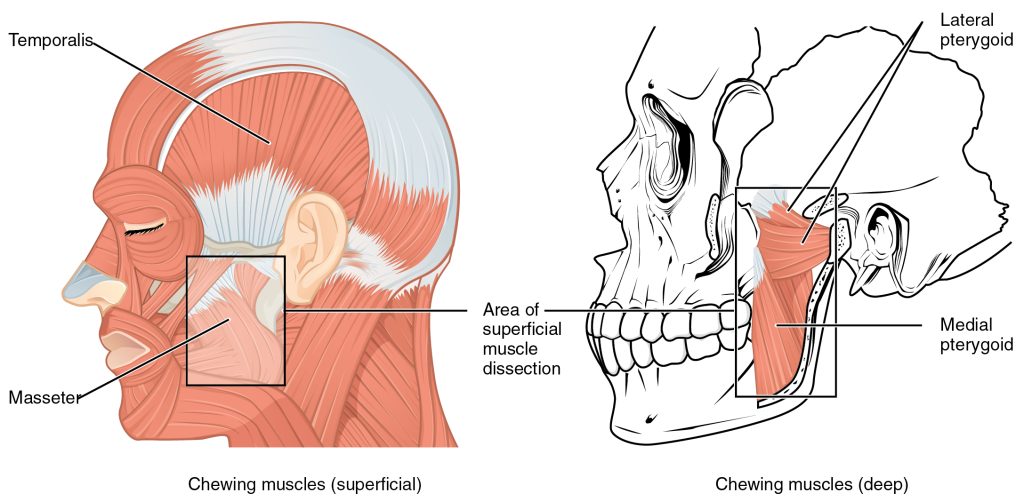

The masseter muscle is the main muscle used for chewing because it elevates the mandible (lower jaw) to close the mouth. It is assisted by the temporalis muscle that retracts the mandible. The temporalis muscle can be felt moving by placing fingers on the patient’s temple as they chew. See Figure 7.10[20] for an illustration of the masseter and temporalis muscles.[21]

Tongue Muscles

Muscles of the tongue are necessary for chewing, swallowing, and speech. Because it is so moveable, the tongue facilitates complex speech patterns and sounds.[22]

Airway and Unconsciousness

When a patient becomes unconscious and is lying supine, the tongue often moves backwards and blocks the airway. This is why it is important to open the airway when performing CPR by using a chin-thrust maneuver. See Figure 7.11[23] for an image of the tongue blocking the airway. In a similar manner, when a patient is administered general anesthesia during surgery, the tongue relaxes and can block the airway. For this reason, endotracheal intubation is performed during surgery with general anesthesia by placing a tube into the trachea to maintain an open airway to the lungs. After surgery, patients often report a sore or scratchy throat for a few days due to the endotracheal intubation.[24]

Swallowing

Swallowing is a complex process that uses 50 pairs of muscles and many nerves to receive food in the mouth, prepare it, and move it from the mouth to the stomach. Swallowing occurs in three stages. During the first stage, called the oral phase, the tongue collects the food or liquid and makes it ready for swallowing. The tongue and jaw move solid food around in the mouth so it can be chewed and made the right size and texture to swallow by mixing food with saliva. The second stage begins when the tongue pushes the food or liquid to the back of the mouth. This triggers a swallowing response that passes the food through the pharynx. During this phase, called the pharyngeal phase, the epiglottis closes off the larynx and breathing stops to prevent food or liquid from entering the airway and lungs. The third stage begins when food or liquid enters the esophagus, and it is carried to the stomach. The passage through the esophagus, called the esophageal phase, usually occurs in about three seconds.[25]

View the following video from Medline Plus on the swallowing process:

Dysphagia is the medical term for swallowing difficulties that occur when there is a problem with the nerves or structures involved in the swallowing process.[27] Nurses are often the first to notice signs of dysphagia in their patients that can occur due to a multitude of medical conditions such as a stroke, head injury, or dementia. For more information about the symptoms, screening, and treatment for dysphagia, go to the "Common Conditions of the Head and Neck" section.

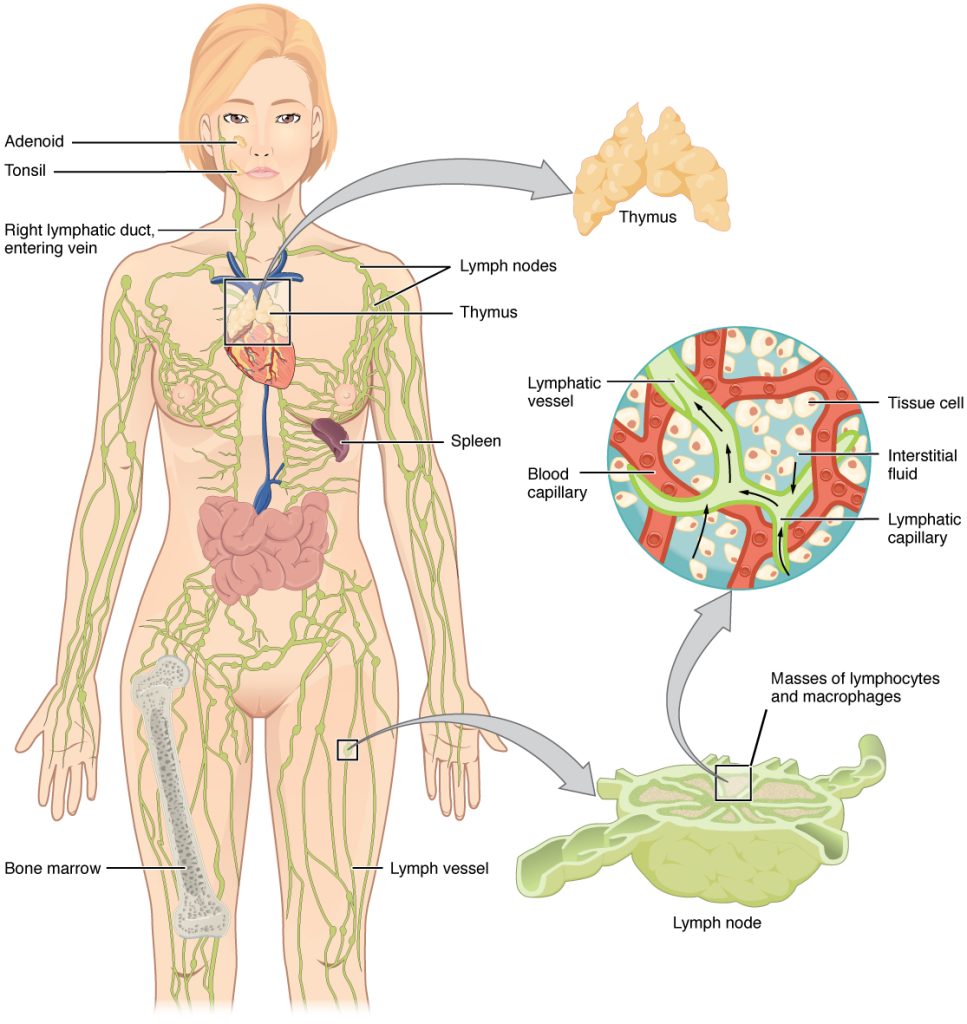

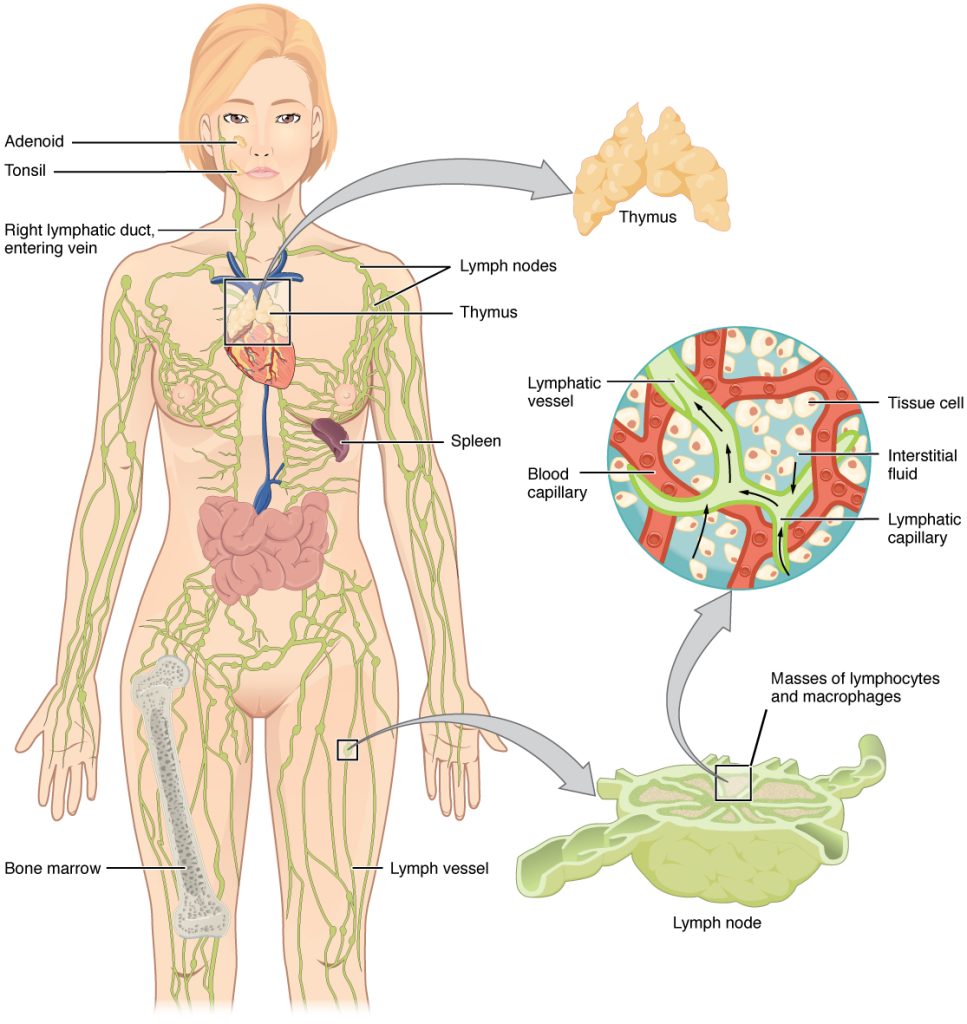

Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system is the system of vessels, cells, and organs that carries excess interstitial fluid to the bloodstream and filters pathogens from the blood through lymph nodes found near the neck, armpits, chest, abdomen, and groin. See Figure 7.12[28] and Figure 7.13[29] for an illustration of the lymph nodes found in the head and neck regions. When a person is fighting off an infection, the lymph nodes in that region become enlarged, indicating an active immune response to infection.[30]

![]“Cervical lymph nodes and level.png” by Mikael Häggström, M.D. is licensed under CC0 1.0 Illustration of lymph nodes in head and neck, with labels](https://opencontent.ccbcmd.edu/app/uploads/sites/30/2024/08/Cervical_lymph_nodes_and_levels-1024x551.png)

To perform and document an accurate assessment of the head and neck, it is important to understand their basic anatomy and physiology.

Anatomy

Skull

The anterior skull consists of facial bones that provide the bony support for the eyes and structures of the face. This anterior view of the skull is dominated by the openings of the orbits, the nasal cavity, and the upper and lower jaws. See Figure 7.1[31] for an illustration of the skull. The orbit is the bony socket that houses the eyeball and the muscles that move the eyeball. Inside the nasal area of the skull, the nasal cavity is divided into halves by the nasal septum that consists of both bone and cartilage components. The mandible forms the lower jaw and is the only movable bone in the skull. The maxilla forms the upper jaw and supports the upper teeth.[32]

The cranium, or "brain case," surrounds and protects the brain that occupies the cranial cavity. See Figure 7.2[33] for an image of the brain within the cranial cavity. The brain case consists of eight bones, including the paired parietal and temporal bones, plus the unpaired frontal, occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid bones.[34]

A suture is an interlocking joint between adjacent bones of the skull and is filled with dense, fibrous connective tissue that unites the bones. In a newborn infant, the pressure from vaginal delivery compresses the head and causes the bony plates to overlap at the sutures, creating a small ridge. Over the next few days, the head expands, the overlapping disappears, and the edges of the bony plates meet edge to edge. This is the normal position for the remainder of the life span and the sutures become immobile.

See Figure 7.3[35] for an illustration of two of the sutures, the coronal and squamous sutures, on the lateral view of the head. The coronal suture is seen on the top of the skull. It runs from side to side across the skull and joins the frontal bone to the right and left parietal bones. The squamous suture is located on the lateral side of the skull. It unites the squamous portion of the temporal bone with the parietal bone. At the intersection of the coronal and squamous sutures is the pterion, a small, capital H-shaped suture line region that unites the frontal bone, parietal bone, temporal bone, and greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The pterion is an important clinical landmark because located immediately under it, inside the skull, is a major branch of an artery that supplies the brain. A strong blow to this region can fracture the bones around the pterion. If the underlying artery is damaged, bleeding can cause the formation of a collection of blood, called a hematoma, between the brain and interior of the skull, which can be life-threatening.[36]

Paranasal Sinuses

The paranasal sinuses are hollow, air-filled spaces located within the skull. See Figure 7.4[37] for an illustration of the sinuses. The sinuses connect with the nasal cavity and are lined with nasal mucosa. They reduce bone mass, lightening the skull, and also add resonance to the voice. When a person has a cold or sinus congestion, the mucosa swells and produces excess mucus that often obstructs the narrow passageways between the sinuses and the nasal cavity. The resulting pressure produces pain and discomfort.[38]

Each of the paranasal sinuses is named for the skull bone that it occupies. The frontal sinus is located just above the eyebrows within the frontal bone. The largest sinus, the maxillary sinus, is paired and located within the right and left maxillary bones just below the orbits. The maxillary sinuses are most commonly involved during sinus infections. The sphenoid sinus is a single, midline sinus located within the body of the sphenoid bone. The lateral aspects of the ethmoid bone contain multiple small spaces separated by very thin, bony walls. Each of these spaces is called an ethmoid air cell.

Anatomy of Nose, Pharynx, and Mouth

See Figure 7.5[39] to review the anatomy of the head and neck. The major entrance and exit for the respiratory system is through the nose. The bridge of the nose consists of bone, but the protruding portion of the nose is composed of cartilage. The nares are the nostril openings that open into the nasal cavity and are separated into left and right sections by the nasal septum. The floor of the nasal cavity is composed of the palate. The hard palate is located at the anterior region of the nasal cavity and is composed of bone. The soft palate is located at the posterior portion of the nasal cavity and consists of muscle tissue. The uvula is a small, teardrop-shaped structure located at the apex of the soft palate. Both the uvula and soft palate move like a pendulum during swallowing, swinging upward to close off the nasopharynx and prevent ingested materials from entering the nasal cavity.[40]

As air is inhaled through the nose, the paranasal sinuses warm and humidify the incoming air as it moves into the pharynx. The pharynx is a tube-lined mucous membrane that begins at the nasal cavity and is divided into three major regions: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx.[41]

The nasopharynx serves only as an airway. At the top of the nasopharynx is the pharyngeal tonsil, commonly referred to as the adenoids. Adenoids are lymphoid tissue that trap and destroy invading pathogens that enter during inhalation. They are large in children but tend to regress with age and may even disappear.[42]

The oropharynx is a passageway for both air and food. The oropharynx is bordered superiorly by the nasopharynx and anteriorly by the oral cavity. The oropharynx contains two sets of tonsils, the palatine and lingual tonsils. The palatine tonsil is located laterally in the oropharynx, and the lingual tonsil is located at the base of the tongue. Similar to the pharyngeal tonsil, the palatine and lingual tonsils are composed of lymphoid tissue and trap and destroy pathogens entering the body through the oral or nasal cavities. See Figure 7.6[43] for an image of the oral cavity and oropharynx with enlarged palatine tonsils.

The laryngopharynx is inferior to the oropharynx and posterior to the larynx. It continues the route for ingested material and air until its inferior end where the digestive and respiratory systems diverge. Anteriorly, the laryngopharynx opens into the larynx, and posteriorly, it enters the esophagus that leads to the stomach. The larynx connects the pharynx to the trachea and helps regulate the volume of air that enters and leaves the lungs. It also contains the vocal cords that vibrate as air passes over them to produce the sound of a person’s voice. The trachea extends from the larynx to the lungs. The epiglottis is a flexible piece of cartilage that covers the opening of the trachea during swallowing to prevent ingested material from entering the trachea.[44]

Muscles and Nerves of the Head and Neck

Facial Muscles

Several nerves innervate the facial muscles to create facial expressions. See Figure 7.7[45] for an illustration of nerves innervating facial muscles. These nerves and muscles are tested during a cranial nerve exam. See more information about performing a cranial nerve exam in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

When a patient is experiencing a cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke), it is common for facial drooping to occur. Facial drooping is an asymmetrical facial expression that occurs due to damage of the nerve innervating a specific part of the face. See Figure 7.8[46] for an image of facial drooping occurring on the patient’s right side of their face.

Neck Muscles

The muscles of the anterior neck assist in swallowing and speech by controlling the positions of the larynx and the hyoid bone, a horseshoe-shaped bone that functions as a solid foundation on which the tongue can move. The head, attached to the top of the vertebral column, is balanced, moved, and rotated by the neck muscles. When these muscles act unilaterally, the head rotates. When they contract bilaterally, the head flexes or extends. The major muscle that laterally flexes and rotates the head is the sternocleidomastoid. The trapezius muscle elevates the shoulders (shrugging), pulls the shoulder blades together, and tilts the head backwards. See Figure 7.9[47] for an illustration of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.[48] Both of these muscles are tested during a cranial nerve assessment. See more information about cranial nerve assessment in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

Jaw Muscles

The masseter muscle is the main muscle used for chewing because it elevates the mandible (lower jaw) to close the mouth. It is assisted by the temporalis muscle that retracts the mandible. The temporalis muscle can be felt moving by placing fingers on the patient’s temple as they chew. See Figure 7.10[49] for an illustration of the masseter and temporalis muscles.[50]

Tongue Muscles

Muscles of the tongue are necessary for chewing, swallowing, and speech. Because it is so moveable, the tongue facilitates complex speech patterns and sounds.[51]

Airway and Unconsciousness

When a patient becomes unconscious and is lying supine, the tongue often moves backwards and blocks the airway. This is why it is important to open the airway when performing CPR by using a chin-thrust maneuver. See Figure 7.11[52] for an image of the tongue blocking the airway. In a similar manner, when a patient is administered general anesthesia during surgery, the tongue relaxes and can block the airway. For this reason, endotracheal intubation is performed during surgery with general anesthesia by placing a tube into the trachea to maintain an open airway to the lungs. After surgery, patients often report a sore or scratchy throat for a few days due to the endotracheal intubation.[53]

Swallowing

Swallowing is a complex process that uses 50 pairs of muscles and many nerves to receive food in the mouth, prepare it, and move it from the mouth to the stomach. Swallowing occurs in three stages. During the first stage, called the oral phase, the tongue collects the food or liquid and makes it ready for swallowing. The tongue and jaw move solid food around in the mouth so it can be chewed and made the right size and texture to swallow by mixing food with saliva. The second stage begins when the tongue pushes the food or liquid to the back of the mouth. This triggers a swallowing response that passes the food through the pharynx. During this phase, called the pharyngeal phase, the epiglottis closes off the larynx and breathing stops to prevent food or liquid from entering the airway and lungs. The third stage begins when food or liquid enters the esophagus, and it is carried to the stomach. The passage through the esophagus, called the esophageal phase, usually occurs in about three seconds.[54]

View the following video from Medline Plus on the swallowing process:

Dysphagia is the medical term for swallowing difficulties that occur when there is a problem with the nerves or structures involved in the swallowing process.[56] Nurses are often the first to notice signs of dysphagia in their patients that can occur due to a multitude of medical conditions such as a stroke, head injury, or dementia. For more information about the symptoms, screening, and treatment for dysphagia, go to the "Common Conditions of the Head and Neck" section.

Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system is the system of vessels, cells, and organs that carries excess interstitial fluid to the bloodstream and filters pathogens from the blood through lymph nodes found near the neck, armpits, chest, abdomen, and groin. See Figure 7.12[57] and Figure 7.13[58] for an illustration of the lymph nodes found in the head and neck regions. When a person is fighting off an infection, the lymph nodes in that region become enlarged, indicating an active immune response to infection.[59]

![]“Cervical lymph nodes and level.png” by Mikael Häggström, M.D. is licensed under CC0 1.0 Illustration of lymph nodes in head and neck, with labels](https://opencontent.ccbcmd.edu/app/uploads/sites/30/2024/08/Cervical_lymph_nodes_and_levels-1024x551.png)

Headache

A headache is a common type of pain that patients experience in everyday life and a major reason for missed time at work or school. Headaches range greatly in severity of pain and frequency of occurrence. For example, some patients experience mild headaches once or twice a year, whereas others experience disabling migraine headaches more than 15 days a month. Severe headaches such as migraines may be accompanied by symptoms of nausea or increased sensitivity to noise or light. Primary headaches occur independently and are not caused by another medical condition. Migraine, cluster, and tension-type headaches are types of primary headaches. Secondary headaches are symptoms of another health disorder that causes pain-sensitive nerve endings to be pressed on or pulled out of place. They may result from underlying conditions including fever, infection, medication overuse, stress or emotional conflict, high blood pressure, psychiatric disorders, head injury or trauma, stroke, tumors, and nerve disorders such as trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic pain condition that typically affects the trigeminal nerve on one side of the cheek.[60]

Not all headaches require medical attention, but some types of headaches can signify a serious disorder and require prompt medical care. Symptoms of headaches that require immediate medical attention include a sudden, severe headache unlike any the patient has ever had; a sudden headache associated with a stiff neck; a headache associated with convulsions, confusion, or loss of consciousness; a headache following a blow to the head; or a persistent headache in a person who was previously headache free.[61]

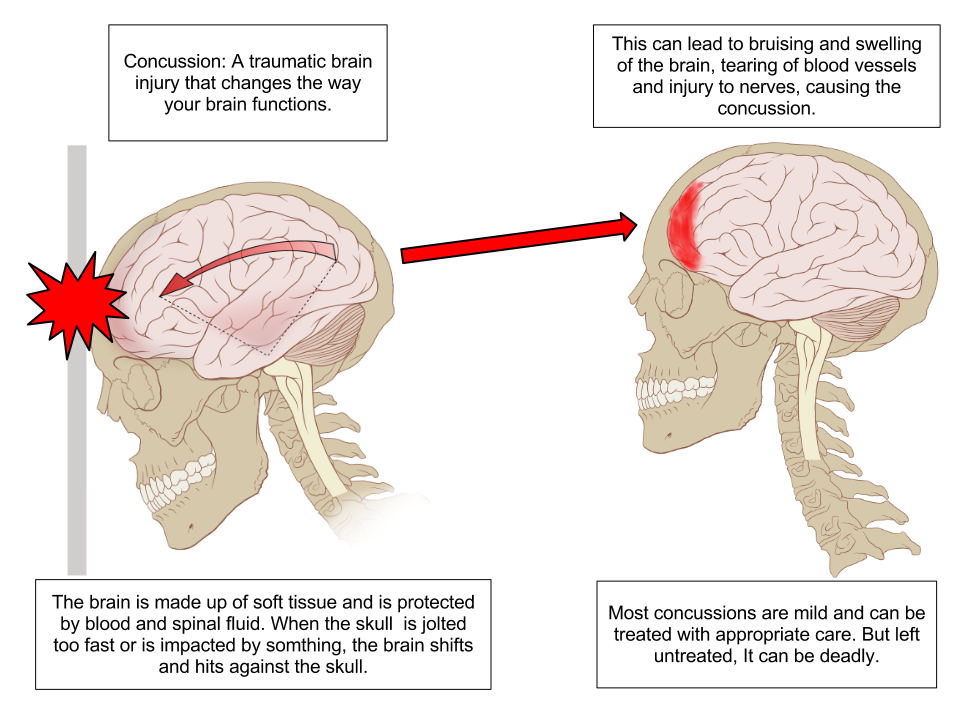

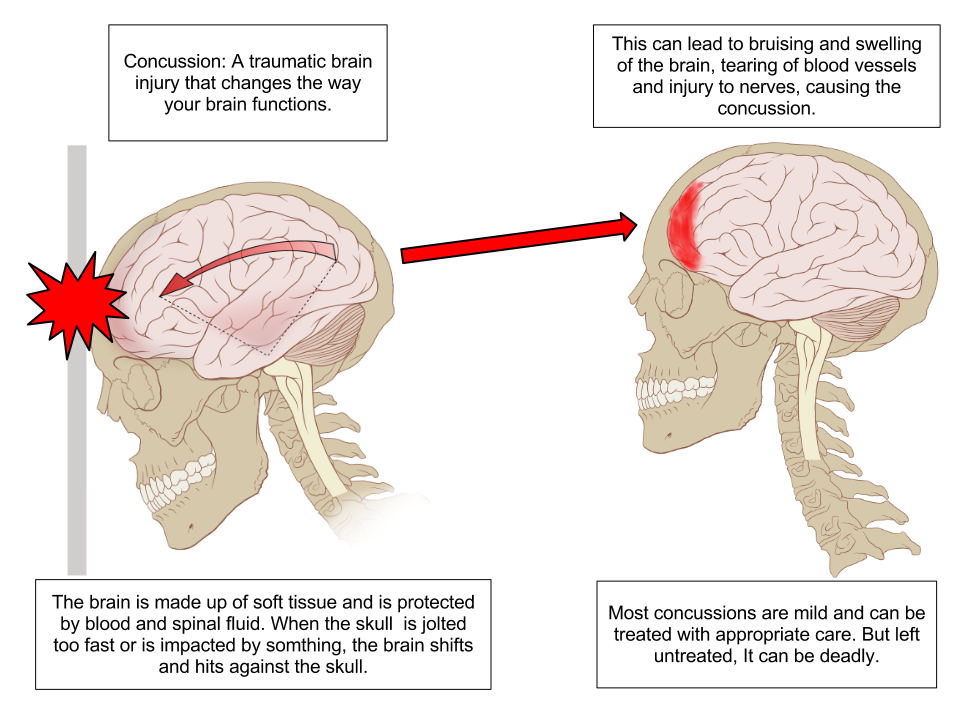

Concussion

A concussion is a type of traumatic brain injury caused by a blow to the head or by a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth. This sudden movement causes the brain to bounce around in the skull, creating chemical changes in the brain and sometimes damaging brain cells.[62] See Figure 7.14[63] for an illustration of a concussion.

Review of Concussions on YouTube[64]

A person who has experienced a concussion may report the following symptoms:

- Headache or “pressure” in head

- Nausea or vomiting

- Balance problems or dizziness or double or blurry vision

- Light or noise sensitivity

- Feeling sluggish, hazy, foggy, or groggy

- Confusion, concentration, or memory problems

- Just not “feeling right” or “feeling down”[65]

The following signs may be observed in someone who has experienced a concussion:

- Can’t recall events prior to or after a hit or fall

- Appears dazed or stunned

- Forgets an instruction, is confused about an assignment or position, or is unsure of the game, score, or opponent

- Moves clumsily

- Answers questions slowly

- Loses consciousness (even briefly)

- Shows mood, behavior, or personality changes[66]

Anyone suspected of experiencing a concussion should immediately be seen by a health care provider or go to the emergency department for further testing.

Read more information about concussion signs and symptoms on the CDC's Concussion Signs and Symptoms webpage.

Head Injury

Head and traumatic brain injuries are major causes of immediate death and disability. Falls are the most common cause of head injuries in young children (ages 0–4 years), adolescents (15–19 years), and the elderly (over 65 years). Strong blows to the brain case of the skull can produce fractures resulting in bleeding inside the skull. A blow to the lateral side of the head may fracture the bones of the pterion. If the underlying artery is damaged, bleeding can cause the formation of a hematoma (collection of blood) between the brain and interior of the skull. As blood accumulates, it will put pressure on the brain. Symptoms associated with a hematoma may not be apparent immediately following the injury, but if untreated, blood accumulation will continue to exert increasing pressure on the brain and can result in death within a few hours.[67]

See Figure 7.15[68] for an image of an epidural hematoma indicated by a red arrow associated with a skull fracture.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is the medical diagnosis for inflamed sinuses that can be caused by a viral or bacterial infection. When the nasal membranes become swollen, the drainage of mucous is blocked and causes pain.

There are several types of sinusitis, including these types:

- Acute Sinusitis: Infection lasting up to 4 weeks

- Chronic Sinusitis: Infection lasting more than 12 weeks

- Recurrent Sinusitis: Several episodes of sinusitis within a year

Symptoms of sinusitis can include fever, weakness, fatigue, cough, and congestion. There may also be mucus drainage in the back of the throat, called postnasal drip. Health care providers diagnose sinusitis based on symptoms and an examination of the nose and face. Treatments include antibiotics, decongestants, and pain relievers.[69]

Pharyngitis

Pharyngitis is the medical term used for infection and/or inflammation in the back of the throat (pharynx). Common causes of pharyngitis are the cold viruses, influenza, strep throat caused by group A streptococcus, and mononucleosis. Strep throat typically causes white patches on the tonsils with a fever and enlarged lymph nodes. It must be treated with antibiotics to prevent potential complications in the heart and kidneys. See Figure 7.16[70] for an image of strep throat in a child.

If not diagnosed as strep throat, most cases of pharyngitis are caused by viruses, and the treatment is aimed at managing the symptoms. Nurses can teach patients the following ways to decrease the discomfort of a sore throat:

- Drink soothing liquids such as lemon tea with honey or ice water.

- Gargle several times a day with warm salt water made of 1/2 tsp. of salt in 1 cup of water.

- Suck on hard candies or throat lozenges.

- Use a cool-mist vaporizer or humidifier to moisten the air.

- Try over-the-counter pain medicines, such as acetaminophen.[71]

Epistaxis

Epistaxis, the medical term for a nosebleed, is a common problem affecting up to 60 million Americans each year. Although most cases of epistaxis are minor and manageable with conservative measures, severe cases can become life-threatening if the bleeding cannot be stopped.[72] See Figure 7.17[73] for an image of a severe case of epistaxis.

The most common cause of epistaxis is dry nasal membranes in winter months due to low temperatures and low humidity. Other common causes are picking inside the nose with fingers, trauma, anatomical deformity, high blood pressure, and clotting disorders. Medications associated with epistaxis are aspirin, clopidogrel, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticoagulants.[74]

To treat a nosebleed, have the victim lean forward at the waist and pinch the lateral sides of the nose with the thumb and index finger for up to 15 minutes while breathing through the mouth.[75] Continued bleeding despite this intervention requires urgent medical intervention such as nasal packing.

Cleft Lip and Palate

During embryonic development, the right and left maxilla bones come together at the midline to form the upper jaw. At the same time, the muscle and skin overlying these bones join together to form the upper lip. Inside the mouth, the palatine processes of the maxilla bones, along with the horizontal plates of the right and left palatine bones, join together to form the hard palate. If an error occurs in these developmental processes, a birth defect of cleft lip or cleft palate may result.

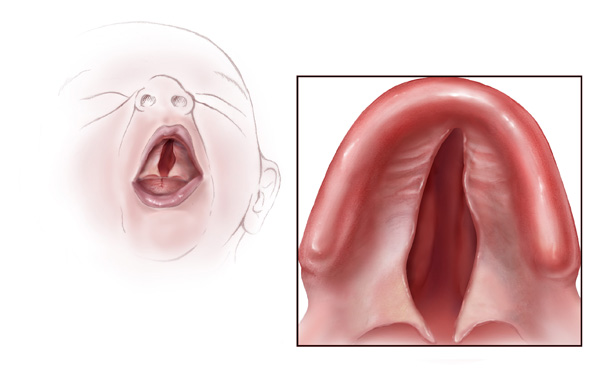

Cleft lip is a common developmental defect that affects approximately 1:1,000 births, most of which are male. This defect involves a partial or complete failure of the right and left portions of the upper lip to fuse together, leaving a cleft (gap). See Figure 7.18[76] for an image of an infant with a cleft lip.

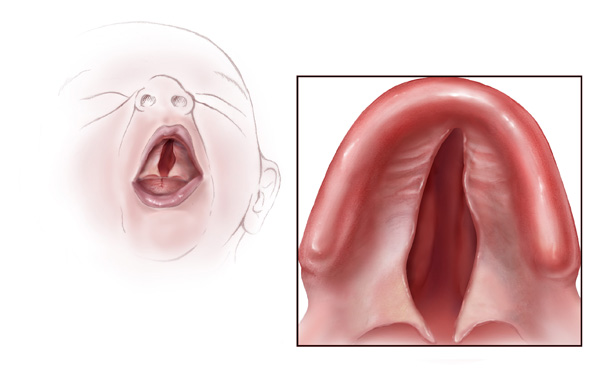

A more severe developmental defect is a cleft palate that affects the hard palate, the bony structure that separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity. See Figure 7.19[77] for an illustration of a cleft palate. Cleft palate affects approximately 1:2,500 births and is more common in females. It results from a failure of the two halves of the hard palate to completely come together and fuse at the midline, thus leaving a gap between the nasal and oral cavities. In severe cases, the bony gap continues into the anterior upper jaw where the alveolar processes of the maxilla bones also do not properly join together above the front teeth. If this occurs, a cleft lip will also be seen. Because of the communication between the oral and nasal cavities, a cleft palate makes it very difficult for an infant to generate the suckling needed for nursing, thus creating risk for malnutrition. Surgical repair is required to correct a cleft palate.[78]

Poor Oral Health

Despite major improvements in oral health for the population as a whole, oral health disparities continue to exist for many racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups in the United States. Healthy People 2020, a nationwide initiative geared to improve the health of Americans, identified improved oral health as a health care goal. A growing body of evidence has also shown that periodontal disease is associated with negative systemic health consequences. Periodontal diseases are infections and inflammation of the gums and bone that surround and support the teeth. Red, swollen, and bleeding gums are signs of periodontal disease. Other symptoms of periodontal disease include bad breath, loose teeth, and painful chewing.[79] In 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 42% of U.S. adults have some form of periodontitis, and almost 60% of adults aged 65 and older have periodontitis. See Figure 7.20[80] for an image of a patient with periodontal disease. Nurses may encounter patients who complain of bleeding gums, or they may discover other signs of periodontal disease during a physical assessment.

Because many Americans lack access to oral care, it is important for nurses to perform routine oral assessment and identify needs for follow-up. If signs and/or symptoms indicate potential periodontal disease, the patient should be referred to a dental health professional for a more thorough evaluation.[81]

Thrush/Candidiasis

Candidiasis is a fungal infection caused by Candida. Candida normally lives on the skin and inside the body without causing any problems, but it can multiply and cause an infection if the environment inside the mouth, throat, or esophagus changes in a way that encourages fungal growth.[82] See Figure 7.21[83] for an image of candidiasis.

Candidiasis in the mouth and throat can have many symptoms, including the following:

- White patches on the inner cheeks, tongue, roof of the mouth, and throat

- Redness or soreness

- Cotton-like feeling in the mouth

- Loss of taste

- Pain while eating or swallowing

- Cracking and redness at the corners of the mouth[84]

Candidiasis in the mouth or throat is common in babies but is uncommon in healthy adults. Risk factors for getting candidiasis as an adult include the following:

- Wearing dentures

- Diabetes

- Cancer

- HIV/AIDS

- Taking antibiotics or corticosteroids including inhaled corticosteroids for conditions like asthma

- Taking medications that cause dry mouth or have medical conditions that cause dry mouth

- Smoking

The treatment for mild to moderate cases of candidiasis infections in the mouth or throat is typically an antifungal medicine applied to the inside of the mouth for 7 to 14 days, such as clotrimazole, miconazole, or nystatin.

"Meth Mouth"

The use of methamphetamine (i.e., meth), a strong stimulant drug, has become an alarming public health issue in the United States. A common sign of meth abuse is extreme tooth and gum decay often referred to as “Meth Mouth.” See Figure 7.22[85] for an image of Meth Mouth.

Signs of Meth Mouth include the following:

- Dry Mouth. Methamphetamines dry out the salivary glands, and the acid content in the mouth will start to destroy the enamel on the teeth. Eventually this will lead to cavities.

- Cracked Teeth. Methamphetamine can make the user feel anxious, hyper, or nervous, so they clench or grind their teeth. You may see severe wear patterns on their teeth.

- Tooth Decay. Methamphetamine users crave beverages high in sugar while they are “high.” The bacteria that feed on the sugars in the mouth will secrete acid, which can lead to more tooth destruction. With methamphetamine users, tooth decay will start at the gum line and eventually spread throughout the tooth. The front teeth are usually destroyed first.

- Gum Disease. Methamphetamine users do not seek out regular dental treatment. Lack of oral health care can contribute to periodontal disease. Methamphetamines also cause the blood vessels that supply the oral tissues to shrink in size, reducing blood flow, causing the tissues to break down.

- Lesions. Users who smoke methamphetamine may present with lesions and/or burns on their lips or gingival inside the cheeks or on the hard palate. Users who snort may present with burns in the back of their throats.[86]

Nurses who notice possible signs of "Meth Mouth" should report their concerns to the health care provider, not only for a referral for dental care, but also for treatment of suspected substance abuse.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is the medical term for difficulty swallowing that can be caused by many medical conditions. Nurses are often the first health care professionals to notice a patient’s difficulty swallowing as they administer medications or monitor food intake. Early identification of dysphagia, especially after a patient has experienced a cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke) or other head injury, helps to prevent aspiration pneumonia.[87] Aspiration pneumonia is a type of lung infection caused by material from the stomach or mouth entering the lungs and can be life-threatening.

Signs of dysphagia include the following:

- Coughing during or right after eating or drinking

- Wet or gurgly sounding voice during or after eating or drinking

- Extra effort or time required to chew or swallow

- Food or liquid leaking from mouth

- Food getting stuck in the mouth

- Difficulty breathing after meals[88]

The Barnes-Jewish Hospital-Stroke Dysphagia Screen (BJH-SDS) is an example of a simple, evidence-based bedside screening tool that can be used by nursing staff to efficiently identify swallowing impairments in patients who have experienced a stroke. See internet resource below for an image of the dysphagia screening tool. The result of the screening test is recorded as a “fail” if any of the five items tested are abnormal (Glasgow Coma Scale < 13, facial/tongue/palatal asymmetry or weakness, or signs of aspiration on the 3-ounce water test) or “pass” if all five items tested were normal. Patients with a failed screening result are placed on nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status until further evaluation is completed by a speech therapist. For more information about using the Glasgow Coma Scale, see the "Assessing Mental Status" section in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

View a PDF sample of a Nursing Bedside Swallow Screen.

Enlarged Lymph Nodes

Lymphadenopathy is the medical term for swollen lymph nodes. In a child, a node is considered enlarged if it is more than 1 centimeter (0.4 inch) wide. See Figure 7.23[89] for an image of an enlarged cervical lymph node.

Common infections such as a cold, pharyngitis, sinusitis, mononucleosis, strep throat, ear infection, or infected tooth often cause swollen lymph nodes. However, swollen lymph nodes can also signify more serious conditions. Notify the health care provider if the patient’s lymph nodes have the following characteristics:

- Do not decrease in size after several weeks or continue to get larger

- Are red and tender

- Feel hard, irregular, or fixed in place

- Are associated with night sweats or unexplained weight loss

- Are larger than 1 centimeter in diameter

The health care provider may order blood tests, a chest X-ray, or a biopsy of the lymph node if these signs occur.[90]

Thyroid

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland located at the front of the neck that controls many of the body’s important functions. The thyroid gland makes hormones that affect breathing, heart rate, digestion, and body temperature. If the thyroid makes too much or not enough thyroid hormone, many body systems are affected. In hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland doesn’t produce enough hormone and many body functions slow down. When the thyroid makes too much hormone, a condition called hyperthyroidism, many body systems speed up.[91]

A goiter is an abnormal enlargement of the thyroid gland that can occur with hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. If you find a goiter when assessing a patient’s neck, notify the health care provider for additional testing and treatment. See Figure 7.24[92] for an image of a goiter.

Headache

A headache is a common type of pain that patients experience in everyday life and a major reason for missed time at work or school. Headaches range greatly in severity of pain and frequency of occurrence. For example, some patients experience mild headaches once or twice a year, whereas others experience disabling migraine headaches more than 15 days a month. Severe headaches such as migraines may be accompanied by symptoms of nausea or increased sensitivity to noise or light. Primary headaches occur independently and are not caused by another medical condition. Migraine, cluster, and tension-type headaches are types of primary headaches. Secondary headaches are symptoms of another health disorder that causes pain-sensitive nerve endings to be pressed on or pulled out of place. They may result from underlying conditions including fever, infection, medication overuse, stress or emotional conflict, high blood pressure, psychiatric disorders, head injury or trauma, stroke, tumors, and nerve disorders such as trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic pain condition that typically affects the trigeminal nerve on one side of the cheek.[93]

Not all headaches require medical attention, but some types of headaches can signify a serious disorder and require prompt medical care. Symptoms of headaches that require immediate medical attention include a sudden, severe headache unlike any the patient has ever had; a sudden headache associated with a stiff neck; a headache associated with convulsions, confusion, or loss of consciousness; a headache following a blow to the head; or a persistent headache in a person who was previously headache free.[94]

Concussion

A concussion is a type of traumatic brain injury caused by a blow to the head or by a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth. This sudden movement causes the brain to bounce around in the skull, creating chemical changes in the brain and sometimes damaging brain cells.[95] See Figure 7.14[96] for an illustration of a concussion.

Review of Concussions on YouTube[97]

A person who has experienced a concussion may report the following symptoms:

- Headache or “pressure” in head

- Nausea or vomiting

- Balance problems or dizziness or double or blurry vision

- Light or noise sensitivity

- Feeling sluggish, hazy, foggy, or groggy

- Confusion, concentration, or memory problems

- Just not “feeling right” or “feeling down”[98]

The following signs may be observed in someone who has experienced a concussion:

- Can’t recall events prior to or after a hit or fall

- Appears dazed or stunned

- Forgets an instruction, is confused about an assignment or position, or is unsure of the game, score, or opponent

- Moves clumsily

- Answers questions slowly

- Loses consciousness (even briefly)

- Shows mood, behavior, or personality changes[99]

Anyone suspected of experiencing a concussion should immediately be seen by a health care provider or go to the emergency department for further testing.

Read more information about concussion signs and symptoms on the CDC's Concussion Signs and Symptoms webpage.

Head Injury

Head and traumatic brain injuries are major causes of immediate death and disability. Falls are the most common cause of head injuries in young children (ages 0–4 years), adolescents (15–19 years), and the elderly (over 65 years). Strong blows to the brain case of the skull can produce fractures resulting in bleeding inside the skull. A blow to the lateral side of the head may fracture the bones of the pterion. If the underlying artery is damaged, bleeding can cause the formation of a hematoma (collection of blood) between the brain and interior of the skull. As blood accumulates, it will put pressure on the brain. Symptoms associated with a hematoma may not be apparent immediately following the injury, but if untreated, blood accumulation will continue to exert increasing pressure on the brain and can result in death within a few hours.[100]

See Figure 7.15[101] for an image of an epidural hematoma indicated by a red arrow associated with a skull fracture.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is the medical diagnosis for inflamed sinuses that can be caused by a viral or bacterial infection. When the nasal membranes become swollen, the drainage of mucous is blocked and causes pain.

There are several types of sinusitis, including these types:

- Acute Sinusitis: Infection lasting up to 4 weeks

- Chronic Sinusitis: Infection lasting more than 12 weeks

- Recurrent Sinusitis: Several episodes of sinusitis within a year

Symptoms of sinusitis can include fever, weakness, fatigue, cough, and congestion. There may also be mucus drainage in the back of the throat, called postnasal drip. Health care providers diagnose sinusitis based on symptoms and an examination of the nose and face. Treatments include antibiotics, decongestants, and pain relievers.[102]

Pharyngitis

Pharyngitis is the medical term used for infection and/or inflammation in the back of the throat (pharynx). Common causes of pharyngitis are the cold viruses, influenza, strep throat caused by group A streptococcus, and mononucleosis. Strep throat typically causes white patches on the tonsils with a fever and enlarged lymph nodes. It must be treated with antibiotics to prevent potential complications in the heart and kidneys. See Figure 7.16[103] for an image of strep throat in a child.

If not diagnosed as strep throat, most cases of pharyngitis are caused by viruses, and the treatment is aimed at managing the symptoms. Nurses can teach patients the following ways to decrease the discomfort of a sore throat:

- Drink soothing liquids such as lemon tea with honey or ice water.

- Gargle several times a day with warm salt water made of 1/2 tsp. of salt in 1 cup of water.

- Suck on hard candies or throat lozenges.

- Use a cool-mist vaporizer or humidifier to moisten the air.

- Try over-the-counter pain medicines, such as acetaminophen.[104]

Epistaxis

Epistaxis, the medical term for a nosebleed, is a common problem affecting up to 60 million Americans each year. Although most cases of epistaxis are minor and manageable with conservative measures, severe cases can become life-threatening if the bleeding cannot be stopped.[105] See Figure 7.17[106] for an image of a severe case of epistaxis.

The most common cause of epistaxis is dry nasal membranes in winter months due to low temperatures and low humidity. Other common causes are picking inside the nose with fingers, trauma, anatomical deformity, high blood pressure, and clotting disorders. Medications associated with epistaxis are aspirin, clopidogrel, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticoagulants.[107]

To treat a nosebleed, have the victim lean forward at the waist and pinch the lateral sides of the nose with the thumb and index finger for up to 15 minutes while breathing through the mouth.[108] Continued bleeding despite this intervention requires urgent medical intervention such as nasal packing.

Cleft Lip and Palate

During embryonic development, the right and left maxilla bones come together at the midline to form the upper jaw. At the same time, the muscle and skin overlying these bones join together to form the upper lip. Inside the mouth, the palatine processes of the maxilla bones, along with the horizontal plates of the right and left palatine bones, join together to form the hard palate. If an error occurs in these developmental processes, a birth defect of cleft lip or cleft palate may result.

Cleft lip is a common developmental defect that affects approximately 1:1,000 births, most of which are male. This defect involves a partial or complete failure of the right and left portions of the upper lip to fuse together, leaving a cleft (gap). See Figure 7.18[109] for an image of an infant with a cleft lip.

A more severe developmental defect is a cleft palate that affects the hard palate, the bony structure that separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity. See Figure 7.19[110] for an illustration of a cleft palate. Cleft palate affects approximately 1:2,500 births and is more common in females. It results from a failure of the two halves of the hard palate to completely come together and fuse at the midline, thus leaving a gap between the nasal and oral cavities. In severe cases, the bony gap continues into the anterior upper jaw where the alveolar processes of the maxilla bones also do not properly join together above the front teeth. If this occurs, a cleft lip will also be seen. Because of the communication between the oral and nasal cavities, a cleft palate makes it very difficult for an infant to generate the suckling needed for nursing, thus creating risk for malnutrition. Surgical repair is required to correct a cleft palate.[111]

Poor Oral Health

Despite major improvements in oral health for the population as a whole, oral health disparities continue to exist for many racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups in the United States. Healthy People 2020, a nationwide initiative geared to improve the health of Americans, identified improved oral health as a health care goal. A growing body of evidence has also shown that periodontal disease is associated with negative systemic health consequences. Periodontal diseases are infections and inflammation of the gums and bone that surround and support the teeth. Red, swollen, and bleeding gums are signs of periodontal disease. Other symptoms of periodontal disease include bad breath, loose teeth, and painful chewing.[112] In 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 42% of U.S. adults have some form of periodontitis, and almost 60% of adults aged 65 and older have periodontitis. See Figure 7.20[113] for an image of a patient with periodontal disease. Nurses may encounter patients who complain of bleeding gums, or they may discover other signs of periodontal disease during a physical assessment.

Because many Americans lack access to oral care, it is important for nurses to perform routine oral assessment and identify needs for follow-up. If signs and/or symptoms indicate potential periodontal disease, the patient should be referred to a dental health professional for a more thorough evaluation.[114]

Thrush/Candidiasis

Candidiasis is a fungal infection caused by Candida. Candida normally lives on the skin and inside the body without causing any problems, but it can multiply and cause an infection if the environment inside the mouth, throat, or esophagus changes in a way that encourages fungal growth.[115] See Figure 7.21[116] for an image of candidiasis.

Candidiasis in the mouth and throat can have many symptoms, including the following:

- White patches on the inner cheeks, tongue, roof of the mouth, and throat

- Redness or soreness

- Cotton-like feeling in the mouth

- Loss of taste

- Pain while eating or swallowing

- Cracking and redness at the corners of the mouth[117]

Candidiasis in the mouth or throat is common in babies but is uncommon in healthy adults. Risk factors for getting candidiasis as an adult include the following:

- Wearing dentures