5.3 General Cardiovascular System Assessment

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

When evaluating a client for possible disorders of the cardiovascular system, the nurse must attend to individual and population risk factors, cultural influence, and socioeconomic factors that may impact preventative and curative health. Client health history, physical examination findings, and diagnostic test results will also play an important role in cardiovascular system assessment.

Risk Factors, Cultural, and Socioeconomic Influences on Cardiovascular System Health

Risk Factors

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a significant global health concern, requiring providers to conduct a comprehensive risk assessment to guide client prevention and management strategies. A thorough client history is foundational for evaluating CVD risk, encompassing both modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors. Understanding contributing risk factors provides essential insights into understanding an individual’s susceptibility to developing CVD and helps health care professionals tailor interventions effectively.

In the context of client history, identifying modifiable risk factors is crucial. Modifiable risk factors are risk factors that an individual can control through their actions, behavior, or lifestyle choices. These include factors such as tobacco use, physical activity, dietary habits, stress management, and sleep habits. Metabolic syndrome is a group of conditions that increases a person’s risk of coronary heart disease, diabetes, and stroke. The conditions include elevated blood pressure, blood glucose, and triglyceride levels, as well as increased waist circumference.[1] Understanding an individual’s modifiable risk factors allows health care providers to provide specific educational interventions to help prevent cardiovascular disease.[2]

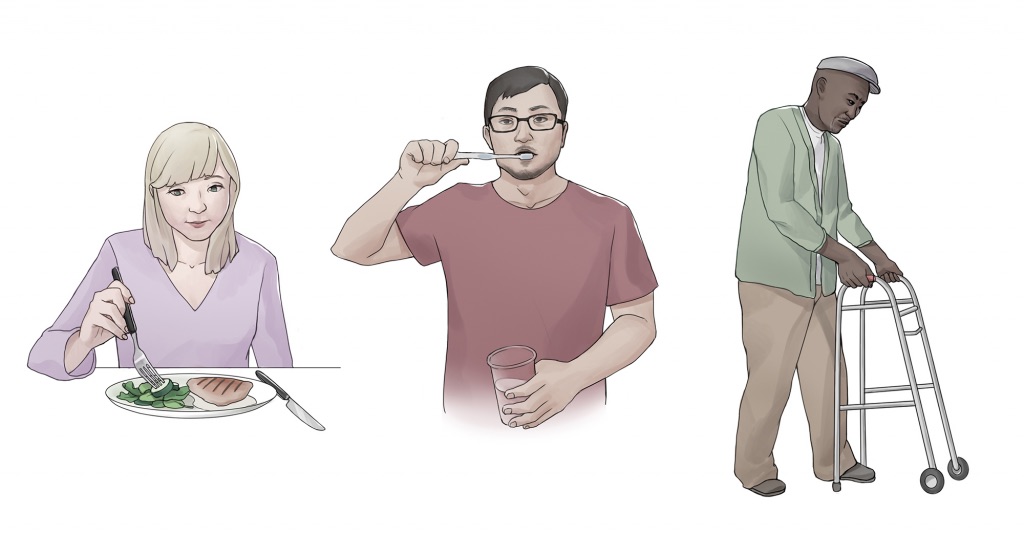

Nutritional history, in particular, plays a pivotal role in cardiovascular health. See Figure 5.16[3] for an image illustrating healthy food choices. When first assessing cardiovascular risk, it can be helpful for individuals to provide a 24-hour food intake log. Providers may ask for individuals to record this for a brief period of time, often one to three days to help understand dietary patterns. Understanding an individual’s food and fluid intake over a brief period provides insight on dietary patterns and identifies deficiencies or excesses. It can be especially helpful to examine an individual’s saturated and trans fat intake, as well as cholesterol, salt, and dietary sugar.[4],[5]

Assessing nonmodifiable risk factors is also important. Nonmodifiable risk factors are those that cannot be changed. Age, gender, and ethnic origin all contribute to an individual’s CVD risk profile. Gathering information about chronic diseases, family history, and medication history helps in gauging potential risk. Family history and genetics play a crucial role in assessing overall risk. A positive family history of coronary artery disease (CAD) in a first-degree relative emerges as a major risk factor, often outweighing other factors such as hypertension, obesity, diabetes, or even sudden cardiac death. Understanding the age, health status, and cause of death of immediate family members helps in gauging the genetic predisposition to CVD.

Social history, including occupation and lifestyle, also provides context for identifying environmental risk factors. By systematically addressing these factors, health care professionals can form a comprehensive risk assessment foundation.[6]

Cultural Factors

Recognizing the role of cultural beliefs and practices in cardiovascular health is integral to a holistic risk assessment. Dietary preferences and lifestyle habits by individuals based on their cultural beliefs may impact their CVD risk. Figure 5.17[7] emphasizes the potential impact of cultural beliefs and practices on dietary preferences. Considering these cultural aspects helps nurses tailor interventions that are culturally responsive and more likely to be effective with diverse clients.[8],[9]

Involving family members and/or significant others responsible for cooking and shopping is invaluable when providing dietary teaching. By engaging them in discussions about healthy food choices and meal preparation, the nurse ensures that interventions align with cultural values and family dynamics, fostering positive, long-term health outcomes.

Socioeconomic Factors

Socioeconomic factors significantly influence cardiovascular risk, contributing to health disparities observed across different populations. Understanding the impact of an individual’s economic status is essential, as financial limitations can impact their access to healthy foods and health care resources.[10]

Additional socioeconomic factors like income, education, and access to health care can also amplify or mitigate CVD risk. Individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds may face challenges in adopting healthy lifestyles due to limited resources or stressful environments. Access to healthy foods, such as fruits and vegetables, may pose a challenge in areas with limited grocery stores or markets. Additionally, nutritious foods are often more expensive and may create a financial burden for individuals with limited income. These factors contribute to health inequalities and highlight the importance of addressing socioeconomic determinants of cardiovascular health.[11]

See the following box for a case scenario illustrating risk factor identification.

Case Scenario: Risk Factor Identification

Maria Angleso is a 45-year-old woman who presents to the clinic for a routine check-up. She has a family history of coronary artery disease (CAD) with her father experiencing a heart attack at the age of 55. Maria is concerned about her cardiovascular health and wants to assess her risk factors. She mentions that she recently lost her job and is now experiencing financial stress. She is also the primary caregiver for her elderly mother, who has limited mobility and requires specialized care.

1. Based on the following scenario, assess Maria for cardiovascular risk factors.

Financial Stress: The recent job loss and financial stress can impact Maria’s cardiovascular health. Stress can lead to unhealthy coping mechanisms, such as poor dietary choices or increased tobacco/alcohol use. Addressing stress management strategies will be crucial.

Dietary Habits: Maria’s dietary habits, influenced by her financial situation, may include the consumption of processed or unhealthy foods due to budget constraints. Addressing her nutritional choices and providing guidance on budget-friendly, heart-healthy meal options can help mitigate this risk factor.

Physical Activity: Because Maria is the primary caregiver for her elderly mother, she may have limited time for physical activity. Encouraging her to incorporate short, regular bouts of physical activity into her daily routine can be beneficial.

Stress Management: The combined stressors of job loss and caregiving responsibilities can impact her mental well-being. Strategies such as mindfulness, relaxation techniques, or counseling can be explored to manage stress effectively.

Family History of CAD: Maria’s family history of CAD with her father having a heart attack at 55 is a nonmodifiable risk factor. It indicates a genetic predisposition to cardiovascular issues, which should be considered when assessing her overall risk.

Age: Maria is 45 years old, which is a nonmodifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Middle age is a critical period for assessing CVD risk.

Caregiver Role: While being a caregiver itself is not a traditional nonmodifiable risk factor, in this scenario, her role as a primary caregiver is nonmodifiable. It affects her ability to allocate time for certain lifestyle modifications.

2. Identify risk factors as modifiable or nonmodifiable.

Modifiable: Financial Stress, Dietary Habits, Physical Activity, Stress Management

Nonmodifiable: Family History, Age, Caregiver Role

Assessment

A comprehensive assessment is essential because cardiovascular disease can impact the functioning of all body systems if the transportation of blood, nutrients, oxygen, and waste products to and from various organs and tissues is affected. A comprehensive assessment includes health history, physical examination, laboratory studies, and diagnostic testing. This section will discuss the generalities of a comprehensive assessment related to the cardiovascular system. Additional details related to specific diseases are described in each cardiovascular condition section in the remainder of the chapter.

Health History

A detailed medical and family history may reveal an underlying cardiovascular disorder. Document personal or family history of cardiovascular disease such as heart attack, heart arrhythmias, valvular disorders, stroke, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or diabetes. Heart disease in first-degree relatives such as parents, siblings, or children can indicate genetic risk for CVD and other cardiac conditions.

Personal risk factors should also be assessed, including the following[12]:

- Past or current tobacco use, including the type and amount consumed and the length of exposure

- Caffeine intake

- Alcohol use, including the number of drinks per week

- Drug use

Physical Assessment

Conducting a thorough examination of all body systems provides the nurse with cues regarding potential cardiovascular disorders. Early identification of abnormal findings and notification of the health care provider can lead to prompt intervention and management and improve client outcomes. Table 5.3a summarizes assessments for each body system for abnormal findings that can be related to cardiovascular disease.

Table 5.3a. Abnormal Findings by Body System Related to CVD[13],[14],[15],[16],[17],[18]

| Body System | Abnormal Findings Related to Possible CVD |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Irregular heart rhythm: Arrhythmias

Bradycardia/Tachycardia Abnormal heart sounds (i.e., murmurs, gallops): Valve disease Elevated blood pressure: Hypertension Weak or absent peripheral pulses: CVD, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease Edema: Heart failure Jugular venous distention (JVD) (distended jugular vein when client is positioned at 45 degrees): Right-sided heart failure Crackles in the lung bases: Left-sided heart failure Cyanosis: CVD or peripheral vascular disease Venous insufficiency: Peripheral edema Arterial insufficiency: Atherosclerosis and arteriosclerosis |

| Respiratory | Dyspnea (shortness of breath), especially on exertion: Coronary artery disease or heart failure

Orthopnea (dyspnea when lying flat): Heart failure Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (sudden nighttime breathlessness): Heart failure Cough with frothy sputum: Pulmonary edema associated with heart failure |

| Neurological | Altered mental status, confusion, or disorientation: Hypoxia from CVD

Weakness or paralysis on one side of the body, difficulty speaking or slurred speech: Stroke or cerebral aneurysm Numbness and tingling (peripheral vascular disease) |

| Renal | Decreased urine output: Heart failure |

| Gastrointestinal | Ascites (abdominal distention): Right-sided heart failure

Hepatomegaly and Splenomegaly: Right-sided heart failure |

| Integumentary | Thickened nails: Impaired oxygen delivery from peripheral vascular disease

Pale, cool extremities: Peripheral vascular disease Hair loss on the lower extremities: Peripheral vascular disease Nonhealing wounds or ulcers on the lower extremities: Peripheral vascular disease Venous staining: Peripheral vascular disease |

Focused Cardiovascular System Assessment

A focused cardiovascular assessment involves assessment of the precordium (area over the heart) to identify signs of potential abnormalities, as well as peripheral assessments.

Precordium Assessment

Assessment of the precordium involves inspection, palpation, and auscultation of heart tones.[19]

Inspection

- Chest Configuration: View the chest configuration for any abnormalities, such as pectus excavatum (depression of the chest) or pectus carinatum (protrusion of the chest).

- Pulsations: Observe any abnormal pulsations or heaves (visible or palpable movements of the chest wall) in the precordial area, which could be indicative of cardiac hypertrophy.

Palpation

- Apical Impulse: Palpate for the point of maximal impulse (PMI), which is the location where the apex of the heart touches the chest wall. It is usually found in the fifth intercostal space at or just medial to the midclavicular line. Note the size, location, and amplitude of the PMI.

- Thrills: Use the palm of your hand to palpate for thrills (vibratory sensations) over the precordium, particularly in areas where murmurs are suspected.

Auscultation

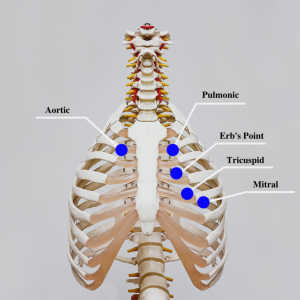

- Follow a systematic pattern when auscultating heart sounds. See Figure 5.18[20] for an illustration of thoracic landmarks for auscultation. The traditional order is as follows:

- Aortic area: Second right intercostal space

- Pulmonic area: Second left intercostal space

- Erb’s point: Third left intercostal space

- Tricuspid area: Fourth left intercostal space at the lower left sternal border

- Mitral area (also referred to as “apical”): Fifth left intercostal space at the midclavicular line

- In each of these areas, listen for the normal heart sounds (S1 and S2). S1 is the first heart sound, often described as “lub,” and corresponds to the closure of the atrioventricular valves (mitral and tricuspid valves). S2 is the second heart sound, described as “dub,” and corresponds to the closure of the semilunar valves (aortic and pulmonic valves). S2 may occur during inspiration, which is considered a normal variation.

- Listen for additional heart sounds, such as S3, S4 murmurs, and pericardial friction rub:

- S3 (also known as a ventricular gallop) is a low frequency heart sound heard shortly after the second heart sound and preceding the normal first heart sound.

- S4 (also known as an atrial gallop) is heard late in the cardiac cycle, just before the first heart sound.

- Murmurs are whooshing or swishing sounds made by rapid, choppy (turbulent) blood flow through the heart that may indicate valvular heart abnormalities. Note the timing, intensity, and location of any murmurs.

- Pericardial friction rub is a high-pitched, scratchy sound that occurs when the inflamed pericardial layers rub against each other. It is typically heard in clients with pericarditis.

Peripheral Assessment

Edema

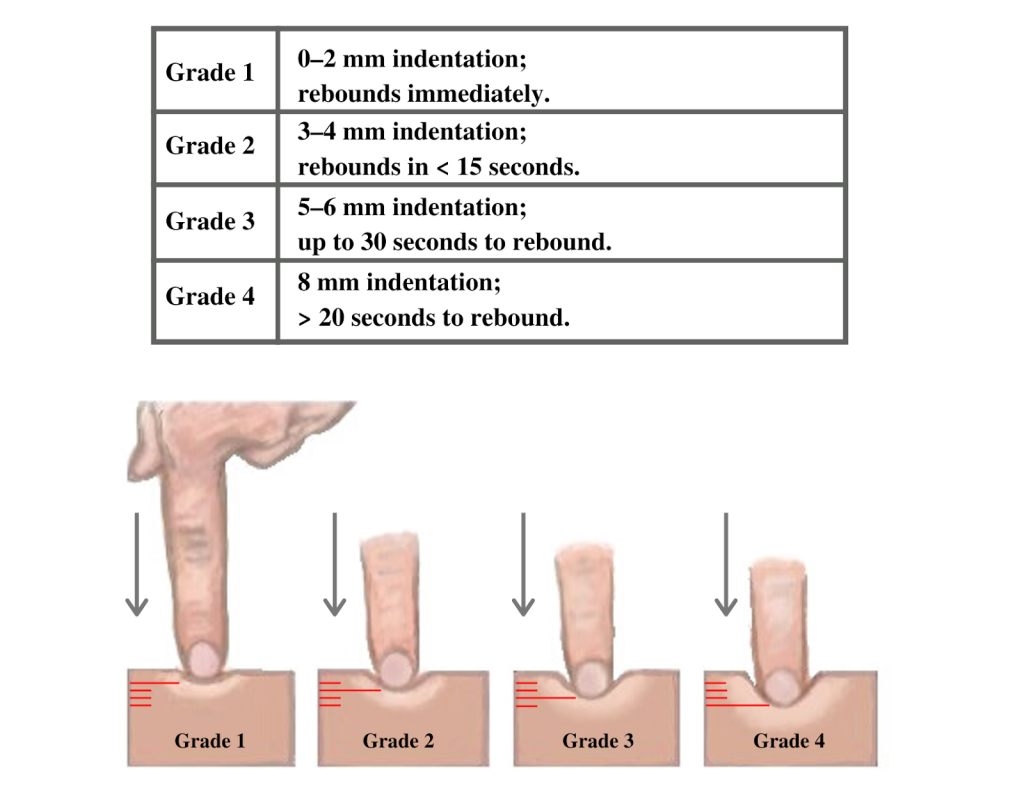

Edema occurs as a result of a buildup of fluid within the tissues. If edema is present on inspection, palpate the area to determine if the edema is pitting or nonpitting. Press on the skin to assess for indentation, ideally over a bony structure, such as the tibia. If no indentation occurs, it is referred to as nonpitting edema. If indentation occurs, it is referred to as pitting edema.

Note the depth of the indention and how long it takes for the skin to rebound back to its original position. The indentation and time required to rebound to the original position are graded on a scale from 1 to 4. Edema rated at 1+ indicates a barely detectable depression with immediate rebound, and 4+ indicates a deep depression with a time lapse of over 20 seconds required to rebound. See Figure 5.19[21] for an illustration of grading edema. Additionally, it is helpful to note edema may be difficult to observe in larger clients. It is also important to monitor for sudden changes in weight, which is considered a probable sign of fluid volume overload.

Capillary Refill

The capillary refill test is performed on the nail beds to monitor perfusion, the amount of blood flow to tissue. Pressure is applied to a fingernail or toenail until it pales, indicating that the blood has been forced from the tissue under the nail. This paleness is called blanching. Once the tissue has blanched, pressure is removed. Capillary refill time is defined as the time it takes for the color to return after pressure is removed. If there is sufficient blood flow to the area, a pink color should return within two to three seconds after the pressure is removed.

Read additional information about performing a focused cardiovascular assessment in the “Cardiovascular Assessment” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Life Span Considerations

Nurses consider characteristics of the pediatric clients and older adults during assessment.[22],[23]

Pediatric Considerations

- Many profound changes occur in a newborn’s cardiovascular anatomy and physiology over the first few days and weeks following birth. It is important to distinguish normal fetal to newborn cardiovascular change and signs of abnormality such as congenital heart defects.

- Newborns have incomplete sympathetic innervation and experience greater vulnerability to environmental and physiological influences without the ability to compensate.

- Infants have higher heart rates and lower blood pressures than adults.

- A small volume of blood loss in small children can be significant. For example, 100 mL of blood loss in an infant weighing 5 kg is 10% of their total blood volume.

- Establishing IV access in infants and children can be challenging due to their small veins and increased subcutaneous tissue.

Older Adult Considerations

- Cardiac valves (especially the mitral and aortic valves) often calcify in older adults, impacting their functionality and resulting in murmurs.

- Pacemaker cells decrease in number, increasing the risk of dysrhythmias.

- Increased fibrous tissue and fat in the SA node can impact the conduction of electrical impulses to the atria.

- Increased conduction time occurs (i.e., the amount of time for an electrical impulse to travel through the SA node, atria, the AV node, the bundle of His, the Purkinje fibers, and ventricles).

- The left ventricle increases in size, impacting the quantity of blood and strength of the contractions.

- Decreased sensitivity of baroreceptors and arteriosclerosis can cause orthostatic hypotension.

- Limited fluid intake (due to prescribed fluid restrictions, an attempt to manage incontinence, or decreased mobility in obtaining and drinking fluids) creates viscous blood and increases the risk for developing thrombi.

- Varicosities may develop due to the loss of elasticity of the veins, weaker leg muscles, and muscle atrophy from less exercise.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory and diagnostic testing are ordered by health care providers to identify and diagnose cardiovascular conditions.

Laboratory Studies

Several key laboratory values that play a vital role in cardiovascular assessment include troponins, CK (creatine kinase), myoglobin, lipids (total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, and LDL), CRP (C-reactive protein), B-type natriuretic peptide, electrolytes, coagulation studies, and thyroid studies. Review normal reference ranges for common diagnostic tests in “Appendix A – Normal Reference Ranges.”

- Troponins: Troponins are myocardial muscle proteins released into the bloodstream with injury to myocardial muscle. Elevated troponin levels indicate cardiac necrosis or an acute myocardial infarction (MI). Troponin T and I are highly specific to cardiac tissue, making them essential markers for diagnosing cardiac events.[24]

- CK (creatine kinase) and CK-MB: CK is an enzyme specific to cells of the brain, myocardium, and skeletal muscle. CK-MB is primarily found in myocardial muscle. CK-MB levels show a predictable rise and fall during three days, with a peak level occurring around 24 hours after the onset of chest pain. Monitoring CK and CK-MB aids in the diagnosis and assessment of MI.[25]

- Myoglobin: Myoglobin is a low-molecular-weight heme protein found in cardiac and skeletal muscle. It is the earliest marker detected after an MI, appearing as early as two hours after the event and declining rapidly after seven hours. However, myoglobin is not cardiac specific, making it less reliable than troponins for MI diagnosis.[26]

- B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP): BNP is a protein that is released by the heart, primarily in response to increased pressure or stress on the heart muscle. This protein plays a crucial role in regulating blood volume and blood pressure. Elevated levels of BNP in the blood can be indicative of heart failure.[27]

- Lipids: Lipid panel laboratory tests include the examination of high-density lipoproteins (HDL), low-density lipoproteins (LDL), and triglycerides. Total cholesterol is a combined measurement of the HDL and LDL numbers. Lipid profile assessments are crucial for identifying cardiovascular risk factors. Elevated total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL levels are associated with atherosclerosis and an increased risk of coronary artery disease (CAD). Conversely, higher levels of HDL are considered protective against CAD.[28]

- CRP (C-reactive protein): CRP is the most studied marker of inflammation. Elevated CRP levels can result from any inflammatory process in the body. While not specific to cardiovascular assessment, measuring CRP is valuable for assessing cardiovascular risk, especially in middle-aged or older individuals. Higher CRP levels may indicate an increased risk of cardiovascular events.[29]

- Electrolytes: Many electrolyte imbalances can affect the heart’s electrical activity and muscle function[30]:

- Sodium (Na+): Sodium is the most common electrolyte in extracellular fluid and plays a crucial role in regulating blood pressure, maintaining fluid balance, and transmitting nerve impulses. Elevated sodium levels can cause high blood pressure and edema.

- Potassium (K+): Potassium is the most common electrolyte inside cells and is essential for normal muscle and nerve function, including heart rhythm. Abnormal potassium levels can result in arrhythmias and muscle weakness and can be caused by kidney disease and certain medications.

- Calcium (Ca2+): Calcium is essential for muscle contraction, blood clotting, and bone health. It is tightly regulated by hormones such as the parathyroid hormone and calcitonin. Abnormal calcium levels can affect muscle and nerve function and bone health.

- Magnesium (Mg2+): Magnesium is involved in numerous biochemical processes, including muscle and nerve function, energy metabolism, and bone health. Abnormal magnesium levels can lead to muscle cramps, irregular heart rhythms, and other issues.

- Coagulation studies: Coagulation studies assess the blood’s ability to clot and include prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). Abnormal results can indicate a risk of clot formation or bleeding.

- Prothrombin time (PT): PT measures the time it takes for blood to clot after a substance called thromboplastin is added to a blood sample. It primarily evaluates the extrinsic and common coagulation pathways. PT is often used to monitor the effect of anticoagulant medications like warfarin and to diagnose bleeding disorders.

- International normalized ratio (INR): INR is a standardized measurement derived from the PT. It is used to ensure consistency in PT results between different laboratories. INR is particularly important for individuals on anticoagulant therapy (e.g., warfarin) to monitor and maintain their blood’s clotting ability within a target range.

- Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT): aPTT measures the time it takes for blood to clot after a substance that activates the intrinsic and common coagulation pathways is added to a blood sample. It is used to assess factors involved in the clotting cascade, including factors VIII, IX, XI, and XII. aPTT is used to diagnose and monitor conditions like hemophilia and to evaluate the effects of anticoagulant medications such as heparin.

- Thrombin time (TT): TT measures the time it takes for fibrinogen to convert into fibrin. It primarily assesses the final step of the clotting process. TT may be used to evaluate specific clotting disorders and fibrinogen abnormalities.

- D-dimer: D-dimer is a marker for the presence of blood clots, specifically the breakdown products of fibrin that result from the dissolution of a blood clot. Elevated levels of D-dimer may suggest the presence of an active blood clotting process in the body. D-dimer tests are often used in the diagnosis of conditions like deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).[31]

- Thyroid function tests: Thyroid hormones help regulate heart rate and cardiac output. Hypothyroidism can lead to bradycardia (slower heart rate), increased cholesterol levels, and increased risk of atherosclerosis, which can contribute to cardiovascular disease. Conversely, hyperthyroidism can cause tachycardia (rapid heart rate) and increased cardiac output, potentially leading to conditions like atrial fibrillation or heart failure. Thyroid hormones also play an important role in regulating the sensitivity of the heart to adrenaline (epinephrine) and norepinephrine, which are hormones that influence heart rate and contractility. Abnormal levels of T4 and T3 can disrupt these processes and affect heart function.[32]

Diagnostic Testing

Providers who suspect a cardiac disorder may initially order a chest X-ray to assess the size of cardiac structures and to check for fluid in the lungs. Other common diagnostic tests related to the cardiovascular system include electrocardiograms (ECG), Holter monitors, echocardiograms, cardiac stress tests, and cardiac catheterization.

Electrocardiogram

An electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG) is an important diagnostic tool to help identify cardiac abnormalities. See Figure 5.20[33] for an image of a client undergoing an ECG and Figure 5.21[34] for an image of a normal ECG strip showing normal sinus rhythm. ECG records the electrical activity of the heart and allows health care professionals to assess the heart’s rhythm and identify various cardiac conduction abnormalities called dysrhythmias or arrhythmias. Cardiac dysrhythmias can range from asymptomatic conditions to life-threatening events that impair the delivery of oxygenated blood to tissues and organs. See Table 5.3b for a summary of common dysrhythmias. An ECG is also a critical tool for diagnosing myocardial ischemia (i.e., a “heart attack”). Specific changes in an ECG tracing can reflect elevation or depression of the ST segment, allowing a provider to identify where potential ischemia or infarction of cardiac tissue may be occurring within the heart.[35]

Nurses must recognize abnormal ECG rhythms requiring prompt intervention. View images of ECGs for Abnormal Rhythms in Nursing Advanced Skills, Chapter 7 Appendix.

Table 5.3b. Common Cardiac Arrhythmias

| Cardiac Rhythm | Rate | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Sinus Rhythm | 60-100 beats per minute (bpm) | Healthy, regular heart rhythm. |

| Sinus Bradycardia | Fewer than 60 bpm in adults | May be normal for well-conditioned athlete, a side effect of medications, or a symptom of various medical conditions. May require a pacemaker if the client is symptomatic. |

| Sinus Tachycardia | Greater than 100 bpm in adults | May be caused by fever, stress, pain, or hypoxia or a symptom of various medical conditions. Transient sinus tachycardia is a normal finding during strenuous physical activity. |

| Atrial Fibrillation (A-Fib) | Irregularly irregular rhythm and rate | Characterized by atrial quivering that can cause decreased cardiac output because the ventricles are not able to fill and pump the appropriate amount of blood with each beat. A-fib increases the risk of stroke. May require a pacemaker. A-fib is a common cardiac arrhythmia with aging individuals. |

| Atrial Flutter | Regular rate | Atrial impulses are fast and regular, with rates between 250-300, and the ventricular rate is not the same as the atrial rate. As a result, the client’s cardiac output decreases. |

| Ventricular Tachycardia (VT or V-tach) | Greater than 100 beats per minute | The ventricular rate is often over 120 beats per minute, resulting in rapidly worsening cardiac output. The client may only be able to tolerate this rapid ventricular rhythm for a short period of time before losing consciousness. V-tach requires emergency response. |

| Ventricular Fibrillation (VF) | No heart rate | Characterized by quivering ventricles with no effective contractions and no cardiac output. This is the most dangerous arrhythmia because of lack of cardiac output and requires immediate initiation of CPR and emergency response. |

| First-Degree Heart Block | Variable | Characterized by a prolonged interval between atrial and ventricular contraction. Can be normal or an early sign of degeneration that can progress to more severe blocks. |

| Second-Degree Heart Block | Variable | Characterized by dropped ventricular beats that can result in decreased cardiac output. May require a pacemaker if symptomatic. |

| Third-Degree Heart Block | Variable | Characterized by a complete electrical dissociation between the atria and ventricles. May require a pacemaker to help maintain adequate cardiac output. |

Read additional information about abnormal heart rhythms and view ECG strips in the “Interpret Basic ECG” chapter in Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills.

Pacemakers

Pacemakers may be inserted in clients to restore normal cardiac conduction and minimize the impact of arrythmias on cardiac output. Pacemakers send electrical impulses to mimic the coordinated actions of the sinus to AV node conduction, restoring efficiency and synchronization to the contraction and relaxation of the heart tissue. Pacemakers are a relatively small battery-powered device that has leads connected to heart tissue. The device can sense the inherent electrical impulses of the heart tissue and override them when needed. The pacemaker includes a generator, a battery, and a small computer to regulate the heart impulses. The pacemaker leads include insulated wires that can be placed inside or onto the cardiac tissue. Pacemakers may be temporary or permanent, depending on the underlying cause of the cardiac arrythmia.

- Transvenous pacemakers are inserted through a vein and threaded into the heart. The generator is commonly placed in a small pectoral pocket in the upper chest.

- Epicardial pacemakers are inserted through an incision in the chest and the leads are attached to the heart. The pacemaker is inserted into a pocket in the skin of the abdomen.

A cardiac provider will determine the type of pacemaker that is required and the settings that will restore appropriate cardiac function to the client. A single chamber pacemaker sends impulses to the right ventricle, whereas a dual-chamber pacemaker can send signals to the upper and lower right heart chambers. Biventricular pacemakers stimulate both lower ventricles of the heart and are used in situations of advanced heart failure.

People who have a permanent pacemaker will require periodic monitoring. The status of the pacemaker will be regularly checked or “interrogated” (often done remotely using a telephone or a secure web-based system) to provide information regarding the heart rhythm, the functioning of the pacemaker leads/generator, the electrical activity initiated by the pacemaker, or inherent to the heart, the battery life and the presence of any abnormal heart rhythms. Individuals with implantable pacemakers should be cautioned regarding the use of magnetic devices directly over the device and should never undergo MRI imaging.[36]

Holter Monitors

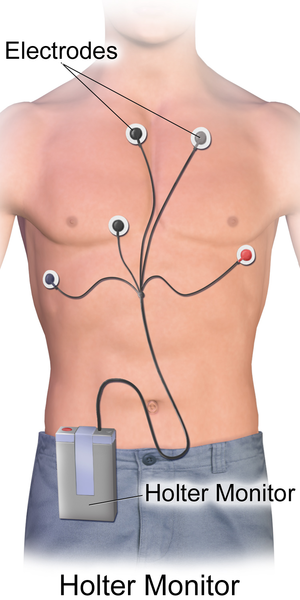

Holter monitors are portable devices that continuously record a client’s heart rhythm and electrical activity over an extended period, typically 24 to 48 hours. See Figure 5.22[37] for an illustration of a Holter monitor. Its primary purpose is to detect and document irregularities in the heart’s electrical patterns, such as arrhythmias, which may not be captured during brief in-office ECGs. Additionally, clients may activate a trigger on a Holter device to denote the occurrence of cardiac symptoms, such as increased shortness of breath, fatigue, or dizziness. A cardiologist can then review the symptom timestamp and accompanying EGC tracing to identify if an arrhythmia occurred at that time.[38]

By providing a thorough real-time analysis of a client’s heart rate and rhythm during their daily activities, the results of a Holter monitor help health care professionals identify and diagnose a variety of cardiac conditions, including atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardias, bradycardias, and heart blocks.

Echocardiogram

A transthoracic echocardiogram is a noninvasive diagnostic test that uses sound waves (ultrasound) to create real-time images of the heart’s structure and function. See Figure 5.23[39] for an image of a pediatric client undergoing a transthoracic echocardiogram. A trained sonographer or cardiologist applies a gel and a transducer to the client’s chest. The transducer is moved to different areas of the chest to obtain various views of the heart, including the heart chambers, valves, walls, and blood flow patterns. Doppler ultrasound is also commonly used during echocardiography to determine the speed and direction of blood flow through the valves and chambers of the heart.

A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) is similar to transthoracic although it is invasive in nature. The provider may order a transesophageal echocardiogram to gain a more detailed view of the heart and aorta. To perform a transesophageal echocardiogram, a probe and ultrasound wand are guided down the esophagus and close to the position of the heart, and the ultrasound is performed. Conscious sedation is administered to enhance client comfort. Both diagnostic tools are very helpful for identifying heart failure, valvular regurgitation, and stenosis.[40],[41]

A key measurement during an echocardiogram is the client’s ejection fraction. Ejection fraction measures the amount of blood the left ventricle of the heart pumps out to the body with each heartbeat. For example, an ejection fraction of 60 percent means that 60 percent of the total amount of blood in the left ventricle is pushed out with each heartbeat. A normal heart’s ejection fraction is between 55 and 70 percent. The ejection fraction is used to diagnose and monitor heart failure.

Cardiac Stress Test

A cardiac stress test (also known as an exercise stress test or treadmill test) is a diagnostic procedure used to evaluate the performance and function of the heart during physical activity. It helps identify potential heart problems, such as coronary artery disease (CAD), arrhythmias, and heart valve issues. During a cardiac stress test procedure, a client is asked to walk on a treadmill or pedal a stationary bicycle with the exercise requirement gradually increasing over time. See Figure 5.24[42] for an image of a cardiac stress test.

During the procedure, client symptoms are monitored for occurrence of chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, and dizziness. The client’s ECG is also closely monitored to detect any changes in heart’s electrical activity during exercise. The test is terminated when the client has achieved a target heart rate, if symptoms of discomfort occur, if the client’s experiences significant ECG changes, or if the maximum duration of exercise has occurred. Cardiac stress tests may also be performed with the administration of medications such as dobutamine or adenosine for individuals who are unable to tolerate exercise-induced stress testing. The medications can simulate the workload that would typically occur during physical exercise.[43]

Cardiac Catheterization

Cardiac catheterization is a valuable diagnostic procedure in the evaluation and management of cardiovascular health alterations. Cardiac catheterization, performed in association with a coronary angiogram, is a diagnostic procedure used to visualize the coronary arteries, heart chambers, and great vessels. It involves the insertion of a thin, flexible tube (catheter) into the blood vessels, usually through the femoral or radial artery, to access the heart and its surrounding structures.[44],[45] See Figure 5.25[46] for an image of a cardiac catheterization procedure with the image of the client’s coronary arteries and heart chambers displayed on the monitor.

Providers order cardiac catheterization for many diagnostic purposes, such as the following:

- Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease (CAD): Identifies blocked or narrowed coronary arteries, guiding decisions about interventions such as angioplasty (use of a balloon to stretch open a blocked artery) or stent (insertion of a small mesh tube to help expand an artery) placement.

- Evaluation of Valvular Heart Disease: Measures pressure gradients across heart valves and assesses valve function.

- Investigation of Congenital Heart Abnormalities: Assesses structural abnormalities of the heart and great vessels in pediatric and adult clients.

- Measurement of Cardiac Function: Directly measures cardiac output, ejection fraction, and other important parameters of cardiac function.

See the following box regarding nursing interventions to prepare a client for cardiac catheterization.

Client Preparation for Cardiac Catheterization[47]

Before a cardiac catheterization procedure, thorough client preparation is needed. This involves collaboration from the nurse and health care team to ensure that all client safety procedural tasks have been addressed.

Informed Consent: The nurse ensures signed informed consent has been obtained and the client understands the procedure, its risks, and alternatives. Concerns are forwarded to the physician before the procedure begins.

Baseline Vital Signs: Baseline vital signs, including blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and temperature are documented. Monitoring trends in these parameters during the procedure is vital for detecting potential complications.

History/Allergy Assessment: A detailed history, including any known allergies, particularly iodine allergies or previous adverse reactions to contrast agents, is obtained. It is crucial to notify the health care team of a history of iodine or iodinated contrast media allergy because contrast agents are commonly used during cardiac catheterization. Allergic reactions can range from mild rashes to severe anaphylactic reactions. Clients with known allergies may require alternative contrast media or premedication to reduce the risk of an allergic response. The client’s renal function should also be assessed because contrast dye can impact renal function.

NPO Status: The client must remain NPO (nothing by mouth) for a specified period before the procedure (usually 6-8 hours), as dictated by agency guidelines.

Medication Management: The client’s current medications should be reviewed for anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents that pose bleeding risks.

IV Access: Intravenous (IV) access is established for administering medications, contrast, and fluids during the procedure, which may be obtained via peripheral and/or central access.

Groin Prep: The groin area is prepared because the femoral artery is often used as the access point for inserting catheters. Prep involves shaving or clipping hair according to agency guidelines and cleansing the area with an antiseptic solution, such as chlorhexidine. If a radial approach is used, cleansing of the wrist and radial artery site with antiseptic is sufficient.

Health Teaching and Support: Health teaching is provided, including what to expect during and after the procedure. Emotional support is provided because many clients experience anxiety related to this invasive procedure.

During cardiac catheterization, a catheter is inserted through the access site and advanced through the blood vessels until it reaches the coronary arteries or the heart chambers. Contrast dye is injected through the catheter, and X-ray imaging is used to visualize the coronary arteries and identify areas of narrowing or blockage. Measurements of pressures and blood oxygen saturations within the heart may be taken to identify abnormalities in valve function. If areas of blockage or narrowing are noted within the coronary arteries, an angioplasty may be performed where a balloon is inflated to help open the coronary artery. After the balloon is inflated, a stent is often inserted to help keep the coronary artery open. After the procedure has been completed, the catheter is removed, and pressure is applied to the access site until bleeding stops.[48] Clients will receive instruction to minimize movement and pressure to the catheter insertion site for a specified period. The site should be closely monitored for recurrent bleeding and pressure should be immediately applied to the insertion site if bleeding recurs. Urinary output is also closely monitored to ensure the contrast dye has not impeded renal function. Additional post-procedure education should include assessing for infection, reporting any signs of chest discomfort, knowing the guidelines for activity progression, etc.

See the following box for a case study related to a cardiac catheterization procedure.

Cardiac Catheterization Case Study

Michael is a 58-year-old man who has been experiencing recurrent episodes of chest pain and shortness of breath. His medical history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and a family history of coronary artery disease (CAD). After a thorough evaluation, it has been determined that a coronary angiography (heart catheterization) is necessary to assess the extent of his coronary artery disease.

1. What are the key steps and considerations in preparing Michael for a coronary angiography procedure?

Medical history, allergies, current medications, renal function, baseline vitals/assessment, client comfort, IV access.

2. How can health care providers ensure that Michael provides informed consent for the coronary angiography procedure?

Provide verbal instruction/written materials or brochures explaining coronary angiography, its purpose, benefits, risks, alternate procedures, and expectations before, during, and after the procedure.

3. Following the coronary angiography, what immediate post-procedure monitoring should be in place for Michael?

Vital signs monitoring, cardiac monitoring, access site monitoring, fluid balance, urine output.

Media Attributions

- pexels-photo-4262171

- Cardiac Ausculation image8-768×768

- Grading Edema

- ambulance-emergency-medic-health-vehicle-rescue

- Holter_Monitor

- 5619843496_1201a6a160_o

- A_cardiac_catheterization_procedure_in_the_Naval_Medical_Center_San_Diego_hospital’s_cardiac_catheterization_laboratory

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, May 18). What Is metabolic syndrome? National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/metabolic-syndrome ↵

- Wilson, P. (2023). Overview of established risk factors for cardiovascular disease. UpToDate. Retrieved August 23, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- “food1.jpg” by bigbrand . is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Fawzy, A. M., & Lip, G. Y. H. (2021). Cardiovascular disease prevention: Risk factor modification at the heart of the matter. The Lancet Regional Health Western Pacific, 17, 100291. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34734203/ ↵

- American Heart Association. (2022, December 6). Understand your risks to prevent a heart attack. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-attack/understand-your-risks-to-prevent-a-heart-attack ↵

- Wilson, P. (2023). Overview of established risk factors for cardiovascular disease. UpToDate. Retrieved August 23, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- “family-setting-the-table-for-dinner” by August de Richlieu, via Pexels.com is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Boudi, F. B. (2021, October 21). Risk factors for coronary artery disease. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/164163-overview ↵

- Schultz, W. M., Heval, K., Lisko, J., Varghese, T., Shen, J., Sandesara, P., Quyyumi, A. A., Taylor, H., Gulati, M., Harold, J., Mieres, J., Ferdinand, K., Menash, G., & Sperling, L. (2018). Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation, 137(20), 2166-2178. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.117.029652 ↵

- Schultz, W. M., Heval, K., Lisko, J., Varghese, T., Shen, J., Sandesara, P., Quyyumi, A. A., Taylor, H., Gulati, M., Harold, J., Mieres, J., Ferdinand, K., Menash, G., & Sperling, L. (2018). Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation, 137(20), 2166-2178. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.117.029652 ↵

- Schultz, W. M., Heval, K., Lisko, J., Varghese, T., Shen, J., Sandesara, P., Quyyumi, A. A., Taylor, H., Gulati, M., Harold, J., Mieres, J., Ferdinand, K., Menash, G., & Sperling, L. (2018). Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation, 137(20), 2166-2178. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.117.029652 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, May 15). About heart disease. https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/about.htm ↵

- Colucci, W. S., & Borlaug, B. A. (2022). Heart failure: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Basile, J., & Bloch, M. J. (2023). Overview of hypertension in adults. UpToDate. Retrieved August 29, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Crea, F., Kolodgie, F., Finn, A. & Virmani, R. (2022). Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes related to atherosclerosis. UpToDate. Retrieved August 20, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Neschis, D. G., & Golden, M. A. (2022). Clinical features and diagnosis of lower extremity peripheral artery disease. UpToDate. Retrieved August 30, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Dalman, R. L., & Mell, M. (2023). Overview of abdominal aortic aneurysm. UpToDate. Retrieved September 1, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Spelman, D. (2022). Complications and outcome of infective endocarditis. UpToDate. Retrieved September 2, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Meyer, T. E. (2022). Auscultation of heart sound. UpToDate. Retrieved August 24, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- “Cardiac Auscultation Areas” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Grading of Edema” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Queensland Pediatric Emergency Care. (2022). How children are different - Anatomical and physiological differences. https://www.childrens.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/179725/how-children-are-different-anatomical-and-physiological-differences.pdf ↵

- Saikia, D., & Mahanta, B. (2019). Cardiovascular and respiratory physiology in children. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 63(9), 690–697. https://doi.org/10.4103/ija.IJA_490_19. ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, January 15). Blood tests for heart disease. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/heart-disease/art-20049357 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, January 15). Blood tests for heart disease. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/heart-disease/art-20049357 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, January 15). Blood tests for heart disease. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/heart-disease/art-20049357 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, January 15). Blood tests for heart disease. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/heart-disease/art-20049357 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, January 15). Blood tests for heart disease. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/heart-disease/art-20049357 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, January 15). Blood tests for heart disease. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/heart-disease/art-20049357 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, January 15). Blood tests for heart disease. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/heart-disease/art-20049357 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, January 15). Blood tests for heart disease. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/heart-disease/art-20049357 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022, January 15). Blood tests for heart disease. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/heart-disease/art-20049357 ↵

- “ambulance-emergency-medic-health-vehicle-rescue.jpg” by unknown author, via pxfuel.com is licensed under CC0 ↵

- “Normal Sinus Rhythm” by Deanna Hoyord is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Prutkin, J. M. (2023). ECG tutorial: Basic principles of ECG analysis. UpToDate. Retrieved August 25, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Olshansky, B. (2022, Nov.). Patient education: Pacemakers (Beyond the basics). UpToDate. Retrieved August 25, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pacemakers-beyond-the-basics ↵

- “Holter_Monitor.png” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Madias, C. (2022). Ambulatory ECG monitoring. UpToDate. Retrieved August 25, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- “5619843496” by Jeremy Miles is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 ↵

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Echocardiogram. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/echocardiogram ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Echocardiogram. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/echocardiogram/about/pac-20393856 ↵

- “a-cardiologist-examining-a-patient-undergoing-cardiac-stress-test” by Los Muertos Crew, via Pexels.com is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Askew, J. W., Chareonthaitawee, P., & Arruda-Olsen, A. M. (2022). Selecting the optimal cardiac stress test. UpToDate. Retrieved August 26, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Kern, M. J. (2022). Cardiac catheterization techniques: Normal hemodynamics. UpToDate. Retrieved August 26, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Velagapudi, P. (2022). Preparing patients for cardiac catheterization and possible coronary artery intervention. UpToDate. Retrieved August 27, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- “A_cardiac_catheterization_procedure_in_the_Naval_Medical_Center_San_Diego_hospital’s_cardiac_catheterization_laboratory.jpg” by Navy Medicine is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- Velagapudi, P. (2022). Preparing patients for cardiac catheterization and possible coronary artery intervention. UpToDate. Retrieved August 27, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Kern, M. J. (2022). Cardiac catheterization techniques: Normal hemodynamics. UpToDate. Retrieved August 26, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

Answer Key to Chapter 5 Learning Activities

Section 5.3 Military Time

- 7:30 PM

- 12:30 AM

- 0900

- 2200

Section 5.4 Household and Metric Equivalents

- 5 mL

- 30 mL

- 500 mg

- 3636 grams

- 0.7 cm

Section 5.5 Rounding

- 6.5

- 6.5

- 5.5

- 5.5

- 0.19

- 0.19

- 0.2

- 0.2

Answers to interactive elements are given within the interactive element.

Use this checklist to perform a "General Survey." Checklists for hand washing, using hand sanitizer, and obtaining vital signs are included in Appendix A.

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Knock, enter the room, greet the patient, and provide for privacy.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Ask the patient their legal name and date of birth to establish two unique identifiers. Verify the information provided in their chart or wristband, if present. Use one of the following for the second verification:

- Scan wristband

- Compare name/DOB to MAR

- Ask staff to verify patient (in settings where wristbands are not worn)

- Compare picture on MAR to patient

- Address patient needs (pain, toileting, glasses/hearing aids) prior to starting assessment. Note if the patient has signs of distress such as difficulty breathing or chest pain. If signs are present, defer general survey and obtain emergency assistance per agency policy.

- Explain the procedure to the patient; ask if they have any questions. Obtain an interpreter as needed if English is not the patient’s primary language.

- Pause and explain to the instructor what you would purposefully observe and assess during a general survey assessment.

- Upon completion of the survey, thank the patient and ask if anything is needed.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene and clean stethoscope.

- Follow agency policy for reporting findings outside of normal range.

- Document the assessment.

Use this checklist to perform a "General Survey." Checklists for hand washing, using hand sanitizer, and obtaining vital signs are included in Appendix A.

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Knock, enter the room, greet the patient, and provide for privacy.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Ask the patient their legal name and date of birth to establish two unique identifiers. Verify the information provided in their chart or wristband, if present. Use one of the following for the second verification:

- Scan wristband

- Compare name/DOB to MAR

- Ask staff to verify patient (in settings where wristbands are not worn)

- Compare picture on MAR to patient

- Address patient needs (pain, toileting, glasses/hearing aids) prior to starting assessment. Note if the patient has signs of distress such as difficulty breathing or chest pain. If signs are present, defer general survey and obtain emergency assistance per agency policy.

- Explain the procedure to the patient; ask if they have any questions. Obtain an interpreter as needed if English is not the patient’s primary language.

- Pause and explain to the instructor what you would purposefully observe and assess during a general survey assessment.

- Upon completion of the survey, thank the patient and ask if anything is needed.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene and clean stethoscope.

- Follow agency policy for reporting findings outside of normal range.

- Document the assessment.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Maria is working on a medical surgical unit and receives a direct admission from the internal medicine clinic. She arrives at the patient’s room to complete the initial admission assessment. All of the following conditions are found. Of these conditions, which of the following should be reported immediately to the health care provider.

- Patient ambulates with assistance of wheeled walker.

- Patient’s BMI is outside of the normal range.

- Patient appears unkempt and has strong body odor.

- Patient is experiencing increased difficulty breathing.

"Vital Signs Case Study” by Susan Jepsen for Lansing Community College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 1.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 2.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 3.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 4.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 5.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 6.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 7.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Maria is working on a medical surgical unit and receives a direct admission from the internal medicine clinic. She arrives at the patient’s room to complete the initial admission assessment. All of the following conditions are found. Of these conditions, which of the following should be reported immediately to the health care provider.

- Patient ambulates with assistance of wheeled walker.

- Patient’s BMI is outside of the normal range.

- Patient appears unkempt and has strong body odor.

- Patient is experiencing increased difficulty breathing.

"Vital Signs Case Study” by Susan Jepsen for Lansing Community College is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 1.

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 2.

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 3.

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 4.

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 5.

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 6.

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 1, Assignment 7.

Sample Documentation of Expected Findings

Mrs. Smith is a 65-year-old patient who appears her stated age. Calm, cooperative, alert, and oriented x 3. Well-groomed with clean clothing and appropriate for weather. Speech is clear, understandable, and follows instructions appropriately. Moves all extremities equally bilaterally with good posture. Gait is smooth and maintains balance without assistance. Skin warm and mucous membranes moist. 5’4” and weighs 143 pounds with BMI of 24 in normal weight category. Vital signs: BP 120/70, pulse 74 and regular, respiratory rate 14, temperature 36.8 Celsius, SpO2 98% on room air.

Sample Documentation of Unexpected Findings

Mrs. Smith is a 65-year-old patient with older appearance than stated age. Slightly agitated during the interview. Oriented to person only and denies pain. Wearing a heavy winter coat on a warm summer day and unclean body odor. Slow to respond to questions and does not follow commands. Neglect noted of right arm. Gait shuffling with stooped posture with no assistive device. 5’4” and weighs 102 pounds with BMI of 17.5 in the underweight category. Vital signs: BP 186/55, pulse 102 and irregular, respiratory rate 22, temperature 38.1 Celsius, and SpO2 88% on room air.

Sample Documentation of Expected Findings

Mrs. Smith is a 65-year-old patient who appears her stated age. Calm, cooperative, alert, and oriented x 3. Well-groomed with clean clothing and appropriate for weather. Speech is clear, understandable, and follows instructions appropriately. Moves all extremities equally bilaterally with good posture. Gait is smooth and maintains balance without assistance. Skin warm and mucous membranes moist. 5’4” and weighs 143 pounds with BMI of 24 in normal weight category. Vital signs: BP 120/70, pulse 74 and regular, respiratory rate 14, temperature 36.8 Celsius, SpO2 98% on room air.

Sample Documentation of Unexpected Findings

Mrs. Smith is a 65-year-old patient with older appearance than stated age. Slightly agitated during the interview. Oriented to person only and denies pain. Wearing a heavy winter coat on a warm summer day and unclean body odor. Slow to respond to questions and does not follow commands. Neglect noted of right arm. Gait shuffling with stooped posture with no assistive device. 5’4” and weighs 102 pounds with BMI of 17.5 in the underweight category. Vital signs: BP 186/55, pulse 102 and irregular, respiratory rate 22, temperature 38.1 Celsius, and SpO2 88% on room air.

Affect: Outward display of one’s emotional state. A “flat” affect with little display of emotion is associated with depression.

AIDET: Mnemonic for introducing oneself in health care that includes Acknowledge, Introduce, Duration, Explanation, and Thank You.[1]

Auscultation: Listening to sounds, such as heart, lung, and bowel sounds, created by organs using a stethoscope.

BMI: A standardized reference range to gauge a patient’s weight status.

Cultural safety: The creation of safe spaces for patients to interact with health professionals without judgment, racial reductionism, racialization, or discrimination.

Developmental stages: A person’s life span can be classified into nine categories of development, including Prenatal Development, Infancy and Toddlerhood, Early Childhood, Middle Childhood, Adolescence, Early Adulthood, Middle Adulthood, Late Adulthood, and Death and Dying.

Family dynamics: Patterns of interactions between family members that influence family structure, hierarchy, roles, values, and behaviors.

General survey assessment: A component of a patient assessment that observes the entire patient as a whole. Observation includes using all five senses to gather cues that provide a guideline for additional focused assessments in areas of concern.

Inspection: The observation of a patient’s anatomical structures.

Medical asepsis: Measures to prevent the spread of infection in health care agencies.

Objective data: Information observed through your sense of hearing, sight, smell, and touch while assessing the patient.

Older adults: People over the age of 65.

Percussion: An advanced physical examination technique where body parts are tapped with fingers to determine their size and if fluid is present.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Includes gloves, gowns, goggles, face shields, and masks, along with environmental controls, to prevent the transmission of infection for patients who are diagnosed or suspected of having an infectious disease.

Physical examination: A systematic data collection method of the body that uses the techniques of inspection, auscultation, palpation, and percussion.

Primary data: Information provided directly by the patient.

Primary survey: A brief observation at the start of a shift or visit to verify the patient is stable by assessing mental status, airway, breathing, and circulation.

Secondary data: Information collected from a family member, chart, or other sources.

Subjective data: Information obtained from the patient and/or family members that offers important cues from their perspectives.

Affect: Outward display of one’s emotional state. A “flat” affect with little display of emotion is associated with depression.

AIDET: Mnemonic for introducing oneself in health care that includes Acknowledge, Introduce, Duration, Explanation, and Thank You.[2]

Auscultation: Listening to sounds, such as heart, lung, and bowel sounds, created by organs using a stethoscope.

BMI: A standardized reference range to gauge a patient’s weight status.

Cultural safety: The creation of safe spaces for patients to interact with health professionals without judgment, racial reductionism, racialization, or discrimination.

Developmental stages: A person’s life span can be classified into nine categories of development, including Prenatal Development, Infancy and Toddlerhood, Early Childhood, Middle Childhood, Adolescence, Early Adulthood, Middle Adulthood, Late Adulthood, and Death and Dying.

Family dynamics: Patterns of interactions between family members that influence family structure, hierarchy, roles, values, and behaviors.

General survey assessment: A component of a patient assessment that observes the entire patient as a whole. Observation includes using all five senses to gather cues that provide a guideline for additional focused assessments in areas of concern.

Inspection: The observation of a patient’s anatomical structures.

Medical asepsis: Measures to prevent the spread of infection in health care agencies.

Objective data: Information observed through your sense of hearing, sight, smell, and touch while assessing the patient.

Older adults: People over the age of 65.

Percussion: An advanced physical examination technique where body parts are tapped with fingers to determine their size and if fluid is present.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Includes gloves, gowns, goggles, face shields, and masks, along with environmental controls, to prevent the transmission of infection for patients who are diagnosed or suspected of having an infectious disease.

Physical examination: A systematic data collection method of the body that uses the techniques of inspection, auscultation, palpation, and percussion.

Primary data: Information provided directly by the patient.

Primary survey: A brief observation at the start of a shift or visit to verify the patient is stable by assessing mental status, airway, breathing, and circulation.

Secondary data: Information collected from a family member, chart, or other sources.

Subjective data: Information obtained from the patient and/or family members that offers important cues from their perspectives.

"'Sickness' is what is happening to the patient. Listen to them."[3]

The profession of nursing is defined by the American Nurses Association as “the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in recognition of the connection of all humanity.[4] Simply put, nurses treat human responses to health problems and/or life processes. Nurses look at each person holistically, including emotional, spiritual, psychosocial, and physical health needs. They also consider problems and issues that the person experiences as a part of a family and a community. To collect detailed information about a patient’s human response to illness and life processes, nurses perform a health history. A health history is part of the Assessment phase of the nursing process. It consists of using directed, focused interview questions and open-ended questions to obtain symptoms and perceptions from the patient about their illnesses, functioning, and life processes. While obtaining a health history, the nurse is also simultaneously performing a general survey. Visit the "General Survey Assessment" chapter for more information.

Learning Objectives

- Establish a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship

- Use effective verbal and nonverbal communication techniques

- Collect health history data

- Modify assessment techniques to reflect variations across the life span and cultural variations

- Document actions and observations

- Recognize and report significant deviations from norms

"'Sickness' is what is happening to the patient. Listen to them."[5]

The profession of nursing is defined by the American Nurses Association as “the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in recognition of the connection of all humanity.[6] Simply put, nurses treat human responses to health problems and/or life processes. Nurses look at each person holistically, including emotional, spiritual, psychosocial, and physical health needs. They also consider problems and issues that the person experiences as a part of a family and a community. To collect detailed information about a patient’s human response to illness and life processes, nurses perform a health history. A health history is part of the Assessment phase of the nursing process. It consists of using directed, focused interview questions and open-ended questions to obtain symptoms and perceptions from the patient about their illnesses, functioning, and life processes. While obtaining a health history, the nurse is also simultaneously performing a general survey. Visit the "General Survey Assessment" chapter for more information.

During a health history, the nurse collects subjective data from the patient, their caregivers, and/or family members using focused and open-ended questions. Before discussing the components of a health history, let’s review some important concepts related to assessment and communicating effectively with patients.

Subjective Versus Objective Data

Obtaining a patient’s health history is a component of the Assessment phase of the nursing process. Information obtained while performing a health history is called subjective data. Subjective data is information obtained from the patient and/or family members and can provide important cues about functioning and unmet needs requiring assistance. Subjective data is considered a symptom because it is something the patient reports. When documenting subjective data in a progress note, it should be included in quotation marks and start with verbiage such as, “The patient reports…” or “The patient’s wife states…” An example of subjective data is when the patient reports, “I feel dizzy.”

A patient is considered the primary source of subjective data. Secondary sources of data include information from the patient's chart, family members, or other health care team members. Patients are often accompanied by their care partners. Care partners are family and friends who are involved in helping to care for the patient. For example, parents are care partners for children; spouses are often care partners for each other, and adult children are often care partners for their aging parents. When obtaining a health history, care partners may contribute important information related to the health and needs of the patient. If data is gathered from someone other than the patient, the nurse should document where the information is obtained.

Objective data is information observed through your senses of hearing, sight, smell, and touch while assessing the patient. Objective data is obtained during the physical examination component of the assessment process. Examples of objective data are vital signs, physical examination findings, and laboratory results. An example of objective data is recording a blood pressure reading of 140/86. Subjective data and objective data are often recorded together during an assessment. For example, the symptom the patient reports, “I feel itchy all over,” is documented in association with the sign of an observed raised red rash located on the upper back and chest.

Addressing Barriers and Adapting Communication

It is vital to establish rapport with a patient before asking questions about sensitive topics to obtain accurate data regarding the mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of a patient’s condition. When interviewing a patient, also consider the patient’s developmental status and level of understanding. Ask one question at a time and allow adequate time for the patient to respond. If the patient does not provide an answer even with additional time, try rephrasing the question in a different way for improved understanding.

If any barriers to communication exist, adapt your communication to that patient’s specific needs.

For more information, visit the "Communication" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Cultural Safety

It is important to conduct a health history in a culturally safe manner. Cultural safety refers to the creation of safe spaces for patients to interact with health professionals without judgment or discrimination. Focus on factors related to a person’s cultural background that may influence their health status. It is helpful to use an open-ended question to allow the patient to share what they believe to be important. For example, ask “I am interested in your cultural background as it relates to your health. Can you share with me what is important to know about your cultural background as part of your health care?”

If a patient’s primary language is not English, it is important to obtain a medical translator, as needed, prior to initiating the health history. The patient's family member or care partner should not interpret for the patient. The patient may not want their care partner to be aware of their health problems or their care partner may not be familiar with correct medical terminology that can result in miscommunication.

During a health history, the nurse collects subjective data from the patient, their caregivers, and/or family members using focused and open-ended questions. Before discussing the components of a health history, let’s review some important concepts related to assessment and communicating effectively with patients.

Subjective Versus Objective Data

Obtaining a patient’s health history is a component of the Assessment phase of the nursing process. Information obtained while performing a health history is called subjective data. Subjective data is information obtained from the patient and/or family members and can provide important cues about functioning and unmet needs requiring assistance. Subjective data is considered a symptom because it is something the patient reports. When documenting subjective data in a progress note, it should be included in quotation marks and start with verbiage such as, “The patient reports…” or “The patient’s wife states…” An example of subjective data is when the patient reports, “I feel dizzy.”

A patient is considered the primary source of subjective data. Secondary sources of data include information from the patient's chart, family members, or other health care team members. Patients are often accompanied by their care partners. Care partners are family and friends who are involved in helping to care for the patient. For example, parents are care partners for children; spouses are often care partners for each other, and adult children are often care partners for their aging parents. When obtaining a health history, care partners may contribute important information related to the health and needs of the patient. If data is gathered from someone other than the patient, the nurse should document where the information is obtained.

Objective data is information observed through your senses of hearing, sight, smell, and touch while assessing the patient. Objective data is obtained during the physical examination component of the assessment process. Examples of objective data are vital signs, physical examination findings, and laboratory results. An example of objective data is recording a blood pressure reading of 140/86. Subjective data and objective data are often recorded together during an assessment. For example, the symptom the patient reports, “I feel itchy all over,” is documented in association with the sign of an observed raised red rash located on the upper back and chest.

Addressing Barriers and Adapting Communication

It is vital to establish rapport with a patient before asking questions about sensitive topics to obtain accurate data regarding the mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of a patient’s condition. When interviewing a patient, also consider the patient’s developmental status and level of understanding. Ask one question at a time and allow adequate time for the patient to respond. If the patient does not provide an answer even with additional time, try rephrasing the question in a different way for improved understanding.

If any barriers to communication exist, adapt your communication to that patient’s specific needs.

For more information, visit the "Communication" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Cultural Safety

It is important to conduct a health history in a culturally safe manner. Cultural safety refers to the creation of safe spaces for patients to interact with health professionals without judgment or discrimination. Focus on factors related to a person’s cultural background that may influence their health status. It is helpful to use an open-ended question to allow the patient to share what they believe to be important. For example, ask “I am interested in your cultural background as it relates to your health. Can you share with me what is important to know about your cultural background as part of your health care?”

If a patient’s primary language is not English, it is important to obtain a medical translator, as needed, prior to initiating the health history. The patient's family member or care partner should not interpret for the patient. The patient may not want their care partner to be aware of their health problems or their care partner may not be familiar with correct medical terminology that can result in miscommunication.

The purpose of obtaining a health history is to gather subjective data from the patient and/or their care partners to collaboratively create a nursing care plan that will promote health and maximize functioning. A comprehensive health history is completed by a registered nurse and may not be delegated. It is typically done on admission to a health care agency or during the initial visit to a health care provider, and information is reviewed for accuracy and currency at subsequent admissions or visits.