Outcome Identification

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Outcome Identification is the third step of the nursing process (and the third Standard of Practice by the American Nurses Association). This standard is defined as, “The registered nurse identifies expected outcomes for a plan individualized to the health care consumer or the situation.” The RN collaborates with the health care consumer, interprofessional team, and others to identify expected outcomes integrating the health care consumer’s culture, values, and ethical considerations. Expected outcomes are documented as measurable goals with a time frame for attainment.[1] Outcome identification is performed by RNs and is outside the scope of practice for LPN/VNs, but LPN/VNs must be aware of expected outcomes for clients in their nursing care plan.

An outcome is a “measurable behavior demonstrated by the client’s response to nursing interventions.”[2] Outcomes should be identified before nursing interventions are planned. After nursing interventions are implemented, the nurse will evaluate if the outcomes were met in the time frame indicated for that client.

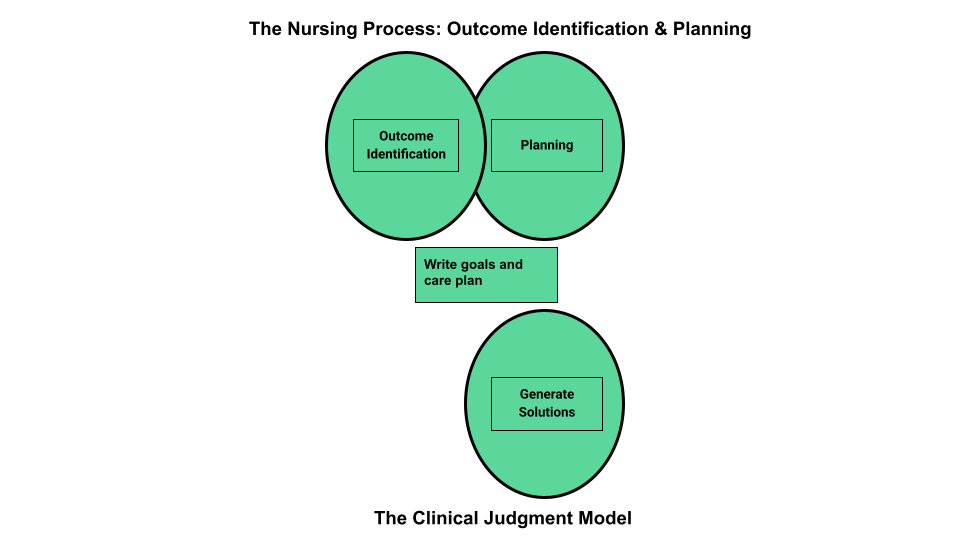

Outcome identification includes setting short- and long-term goals and then creating specific expected outcome statements for each nursing diagnosis. See Figure 4.9a for an illustration of how the Outcome Identification phase of the nursing process correlates to the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Model.[3]

Short-Term and Long-Term Goals

Nursing care should always be individualized and client centered. No two people are the same, and neither should nursing care plans be the same for two people. Goals and outcomes should be tailored specifically to each client’s needs, values, and cultural beliefs. Clients and family members should be included in the goal-setting process when feasible. Involving clients and family members promotes awareness of identified needs, ensures realistic goals, and motivates their participation in the treatment plan to achieve the mutually agreed upon goals and live life to the fullest with their current condition.

The nursing care plan is a road map used to guide client care so that all health care providers are moving toward the same client goals. Goals are broad statements of purpose that describe the overall aim of care. Goals can be short- or long-term. The time frame for short- and long-term goals is dependent on the setting in which the care is provided. For example, in a critical care area, a short-term goal might be set to be achieved within an 8-hour nursing shift, and a long-term goal might be in 24 hours. In contrast, in an outpatient setting, a short-term goal might be set to be achieved within one month and a long-term goal might be within six months.

A nursing goal is the overall direction in which the client must progress to improve the problem/nursing diagnosis and is often the opposite of the problem.

Example of a Broad Goal

Refer to Scenario C in the “Assessment” section of this chapter. Ms. J. had a priority nursing diagnosis of Excess Fluid Volume. A broad goal would be, “Ms. J. will achieve a state of fluid balance.”

Expected Outcomes

Goals are broad, general statements, but outcomes are specific and measurable. Expected outcomes are statements of measurable action for the client within a specific time frame that are responsive to nursing interventions. Nurses may create expected outcomes independently or refer to classification systems for assistance. Just as NANDA-I creates and revises standardized nursing diagnoses, a similar classification and standardization process exists for expected nursing outcomes. The Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) is a list of over 330 nursing outcomes designed to coordinate with established NANDA-I diagnoses.[4]

Client-Centered

Outcome statements are always client-centered. They should be developed in collaboration with the client and individualized to meet a client’s unique needs, values, and cultural beliefs. They should start with the phrase “The client will…” Outcome statements should be directed at resolving the defining characteristics the client is exhibiting for the nursing diagnosis. Additionally, the outcome must be something the client would like to achieve.

Outcome statements should contain five components easily remembered using the “SMART” mnemonic:[5]

- Specific

- Measurable

- Attainable/Action oriented

- Relevant/Realistic

- Timeframe

See Figure 4.9[6] for an image of the SMART components of outcome statements. Each of these components is further described in the following subsections.

Specific

Outcome statements should state precisely what is to be accomplished. See examples of a not specific and a specific outcome in the following box.

Example

- Not specific outcome: “The client will increase the amount of exercise.”

- Revised as a specific outcome: “The client will participate in a bicycling exercise session daily for 30 minutes.”

Additionally, only one action should be included in each expected outcome. See examples in the following box.

Example

- More than one action: “The client will walk 50 feet three times a day with standby assistance of one and will shower in the morning until discharge” is actually two goals written as one. The outcome of ambulation should be separate from showering for precise evaluation. For instance, the client could shower but not ambulate, which would make this outcome statement very difficult to effectively evaluate.

- Revised to create two outcome statements so each can be measured: The client will walk 50 feet three times a day with standby assistance of one until discharge. The client will shower every morning until discharge.

Measurable

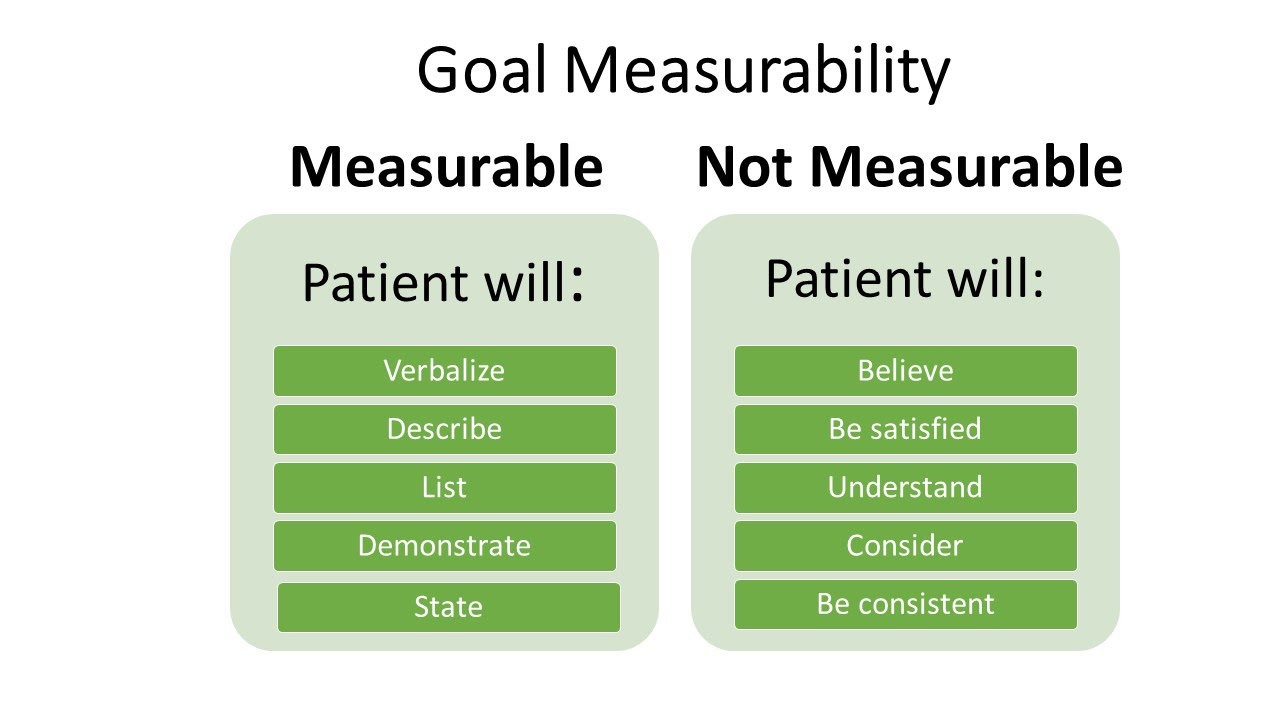

Measurable outcomes have numeric parameters or other concrete methods of judging whether the outcome was met. It is important to use objective data to measure outcomes. If terms like “acceptable” or “normal” are used in an outcome statement, it is difficult to determine whether the outcome is attained. Refer to Figure 4.10[7] for examples of verbs that are measurable and not measurable in outcome statements.

Examples of a non-measurable outcome revised to a measurable outcome is described in the following box.

Example

- Not measurable outcome: “The client will drink adequate fluid amounts every shift.”

- Revised into a measurable outcome: “The client will drink 24 ounces of fluids during every day shift (0600-1400).”

Action-Oriented and Attainable

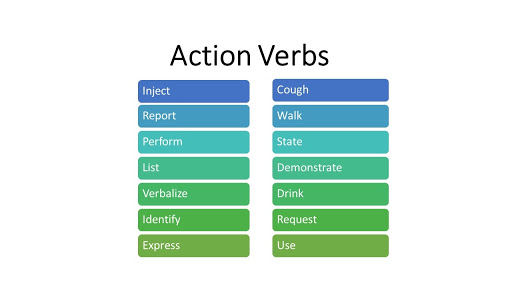

Outcome statements should be written so that there is a clear action to be taken by the client or significant others. This means that the outcome statement should include a verb. Refer to Figure 4.11[8] for examples of action verbs.

An example of a non-action-oriented outcome revised to an action-oriented outcome is provided in the following box.

Example

- Not action-oriented outcome: “The client will get increased physical activity.”

- Revised into an action-oriented outcome: “The client will list three types of aerobic activity that he would enjoy completing every week.”

Realistic and Relevant

Realistic outcomes consider the client’s physical and mental condition; their cultural and spiritual values, beliefs, and preferences; and their socioeconomic status in terms of their ability to attain these outcomes. Consideration should be also given to disease processes and the effects of conditions such as pain and decreased mobility on the client’s ability to reach expected outcomes. Other barriers to outcome attainment may be related to health literacy or lack of available resources. Outcomes should always be reevaluated and revised for attainability as needed. If an outcome is not attained, it is commonly because the original time frame was too ambitious, or the outcome was not realistic for the client.

See an example of how to revise an outcome that is not realistic into a realistic outcome in the following box.

Example

- Not realistic outcome: “The client will jog one mile every day when starting the exercise program.”

- Revised into a realistic outcome: “The client will walk ½ mile three times a week for two weeks.”

Time Limited

Outcome statements should include a time frame for evaluation. The time frame depends on the intervention and the client’s current condition. Some outcomes may need to be evaluated every shift, whereas other outcomes may be evaluated daily, weekly, or monthly. During the evaluation phase of the nursing process, the outcomes will be assessed according to the time frame specified for evaluation. If it has not been met, the nursing care plan should be revised.

See an example an outcome that is not time limited revised into a time limited outcome in the following box.

Example

- Not time limited: “The client will stop smoking cigarettes.”

- Time limited: “The client will complete the smoking cessation plan by December 12, 2025.“

Putting It Together

An example of a SMART outcome for Scenario C is provided in the following box.

Example of a SMART Expected Outcome

Refer to Scenario C in the “Assessment” section of this chapter. Ms. J.’s priority nursing diagnosis statement was Excess Fluid Volume related to excess fluid intake as manifested by bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs, bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the ankles and feet, an increase weight of ten pounds, and the client reports, “My ankles are so swollen.”

The broad goal was, “Ms. J. will achieve a state of fluid balance.”

An example of a SMART expected outcome to achieve this broad goal is, “The client will have clear bilateral lung sounds within the next 24 hours.”

Media Attributions

- Outcome Identification

- SMART-goals

- Slide1

- unnamed (1)

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., & Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2018-2020. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- “Outcome Identification in the Nursing Process Compared to the NCJMM” by Tami Davis is licensed by CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Johnson, M., Moorhead, S., Bulechek, G., Butcher, H., Maas, M., & Swanson, E. (2012). NOC and NIC linkages to NANDA-I and clinical conditions: Supporting critical reasoning and quality care. Elsevier. ↵

- Campbell, J. (2020). SMART criteria. Salem Press Encyclopedia. ↵

- “SMART-goals.png” by Dungdm93 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Measurable Outcomes” by Valerie Palarski for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Action Verbs” by Valerie Palarski for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

Reality Shock

As a new graduate transitions into the role of being a registered nurse (RN), it is very common to experience something called “reality shock.” Although Kramer’s “Reality Shock” theory is several decades old, it continues to apply to new nurses transitioning to their new role through a process of learning and growing. Kramer’s Reality Shock theory characterizes four phases of transitioning into a new role referred to as the honeymoon, shock, recovery, and resolution phases[1]:

- Honeymoon phase: The first phase occurs when the newly graduated RN is excited to join the nursing profession and it is everything they imagined. During this phase, the new nurse is typically paired up with a preceptor RN to orient them to the new role.

- Shock phase: The second phase is when the new RN is the most vulnerable. They are moved off orientation and independently perform tasks without the guidance of their preceptor. The RN role is often more difficult than the new nurse previously imagined. The new RN realizes their expectations associated with the nursing role may be inconsistent with the actual responsibilities. During this phase, negative feelings regarding their new profession may arise, and the new RN is at greatest risk for leaving the unit or quitting.

- Recovery phase: The third phase is when new RNs begin to have positive feelings towards their profession again. During this phase, the new RN is able to reflect on their experiences and develop a clear understanding of their responsibilities and role expectations. The novice RN typically experiences decreased tension and anxiety and begins to assist other RNs as needed.

- Resolution phase: The fourth and final phase is usually at the end of the first year of the new position. The new RN can visualize how the role contributes to the profession, and work expectations are easily met.

Transitioning Into Practice

Over the years, the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) has researched the complex issue of retaining new nursing graduates and found the inability of new nurses to properly transition into practice can have grave consequences. New nurses care for sicker patients in increasingly complex health settings and feel increased stress levels. As a result, new nurses are involved in more patient safety and practice errors than experienced nurses. It has been reported by the NCSBN that within the first year of employment, 25% of novice RNs leave their nursing positions.[2]

There are several potential strategies for helping new nurses transition into practice. The first step of the transition is being aware of “reality shock” and the phases of the transition process. A thorough orientation process with an experienced preceptor is a traditional strategy for transitioning into a new nursing position. A newer strategy being implemented in some agencies is a nurse residency program.

Orientation may last anywhere from one to four months, but can be longer depending on the specialty (e.g., Intensive Care or Labor and Delivery). Orientation is based on the new nurse’s demonstration and completion of competencies. During this time, the novice RN will work with a preceptor to experience all aspects of the role.

Preceptors are experienced and competent RNs who serve as a role model and a resource to a newly hired nurse. Preceptors have the knowledge, skills, and the ability to coach the new RN into the nursing role and answer their questions. The preceptor also evaluates a new hire’s performance and provides feedback for improvement.

Nurse residency programs provide additional professional development support for all newly licensed nurses. Nurse residency programs vary from institution to institution, but many start around the time the new graduate ends their orientation with a preceptor and continue to provide routine support throughout the year. Residency programs are structured to provide a variety of learning opportunities, including nursing skill development, peer networking, and mentorship. The goal of nurse residency programs is to provide organizational support for newly licensed nurses during the critical phase of transitioning from student to professional nurse.[3] See Figure 11.5[4] for an image of new nurses participating in a nurse residency program.

Benner’s Novice to Expert Theory

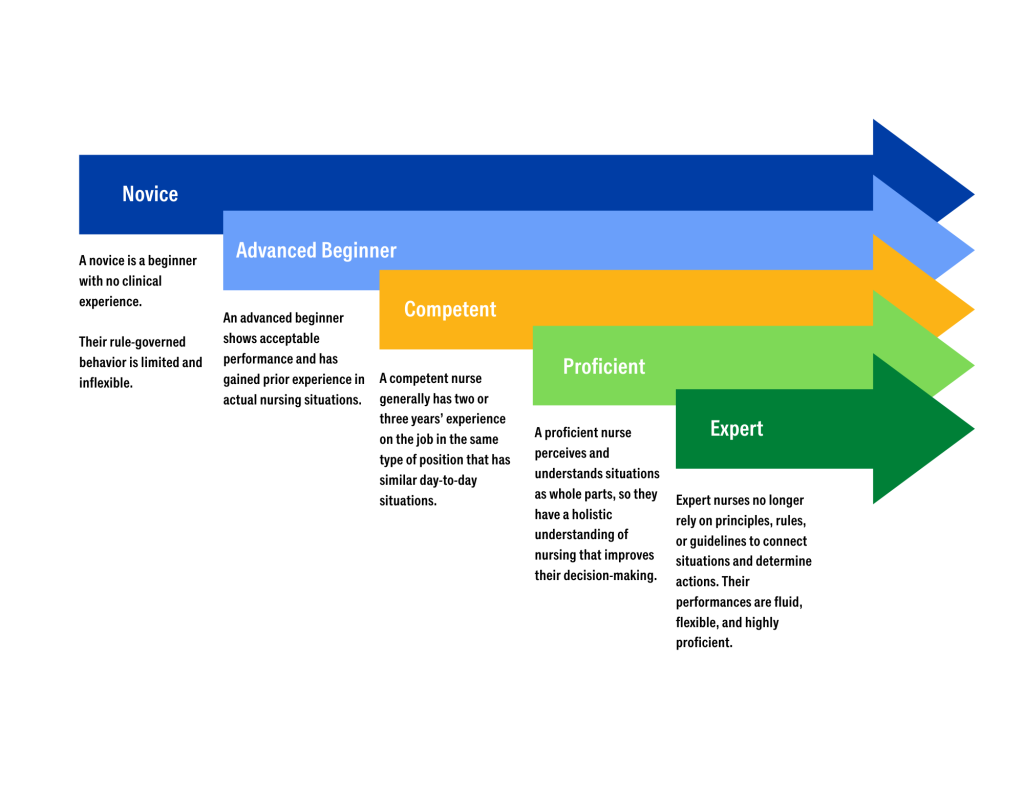

As a nursing graduate transitions into a new nursing role, a well-known theory called “Benner’s Novice to Expert Theory” explains how new hires develop skills and a holistic understanding of patient care over time, resulting from a combination of a strong educational foundation and thorough clinical experiences. See Figure 11.6[5] for an illustration of Benner’s Novice to Expert Theory. Benner’s theory identifies five levels of nursing experience: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert.[6]

- A novice is a beginner with no clinical experience. They are taught general rules to help perform tasks, and their rule-governed behavior is limited and inflexible. In other words, they are told what to do and simply follow instructions.

- An advanced beginner shows acceptable performance and has gained prior experience in actual nursing situations. This experience helps the nurse recognize recurring patterns of patient symptoms and behaviors. An advanced beginner begins to formulate strategies, based on their previous experiences, to guide actions.

- A competent nurse generally has two or three years’ experience on the job in the same type of position that has similar day-to-day situations. Competent nurses become aware of long-term goals and gain perspective from planning their own actions. This helps them achieve greater efficiency and organization.

- A proficient nurse perceives and understands situations as whole parts, so they have a holistic understanding of nursing that improves their decision-making. Proficient nurses have learned what to expect in various patient situations and how to modify plans as needed.

- Expert nurses no longer rely on principles, rules, or guidelines to connect situations and determine actions. They have a deeper background of experience and an intuitive grasp of clinical situations. Their performances are fluid, flexible, and highly proficient.[7]

Mentorship

The value of mentorship in the nursing profession is immense, impacting both the personal and professional development of nurses and the overall quality of patient care. Mentorship involves experienced nurses providing guidance, support, and knowledge to less experienced or new nurses, fostering their growth and integration into the profession. This relationship is essential for building a competent, confident, and resilient nursing workforce.[8]

One of the primary benefits of mentorship is the enhancement of clinical skills and knowledge. Experienced mentors share their expertise, clinical insights, and practical tips with mentees, helping them develop critical thinking and problem-solving abilities. This hands-on learning experience is invaluable, as it bridges the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. Through mentorship, new nurses gain confidence in their clinical competencies, leading to improved patient care and safety.[9]

Mentorship also plays a crucial role in professional development. Mentors guide mentees in setting career goals, navigating career paths, and pursuing continuing education opportunities. They offer advice on advancing in the profession, whether through specialization, leadership roles, or academic achievements. This guidance helps nurses achieve their professional aspirations and contribute more effectively to the health care system. Additionally, mentors often serve as role models, demonstrating the qualities and behaviors essential for success in nursing.[10]

The supportive nature of mentorship fosters emotional and psychological well-being. The transition from nursing school to clinical practice can be challenging and stressful. Having a mentor provides new nurses with a trusted confidant who offers encouragement, listens to concerns, and provides constructive feedback. This support system helps reduce feelings of isolation and burnout, promoting job satisfaction and retention. Mentors can also help new nurses develop coping strategies and resilience, which are critical for long-term success in the demanding field of health care.[11]

Mentorship contributes to the creation of a positive and collaborative workplace culture. By fostering strong relationships between experienced and novice nurses, mentorship programs encourage teamwork, mutual respect, and knowledge sharing. This collaborative environment enhances communication, reduces errors, and improves overall patient outcomes. Furthermore, a culture of mentorship promotes lifelong learning and continuous improvement, essential elements for maintaining high standards of care in a rapidly evolving health care landscape. For mentors, the experience is also enriching and rewarding. Mentoring provides opportunities for professional growth, leadership development, and personal satisfaction. It allows experienced nurses to reflect on their own practices, stay current with new trends and technologies, and contribute to the future of the nursing profession. The act of mentoring fosters a sense of purpose and fulfillment, reinforcing the mentor's commitment to the profession and enhancing their own career satisfaction.[12]

Mentorship is a cornerstone of the nursing profession, offering substantial benefits to individual nurses, health care organizations, and patients. It enhances clinical skills, supports professional development, fosters emotional well-being, and promotes a positive workplace culture. By investing in mentorship programs, health care organizations can ensure the growth and success of their nursing staff, ultimately leading to higher quality care and better patient outcomes.

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style Case Study. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[13]