Basic Concepts Related to Wounds

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Phases of Wound Healing

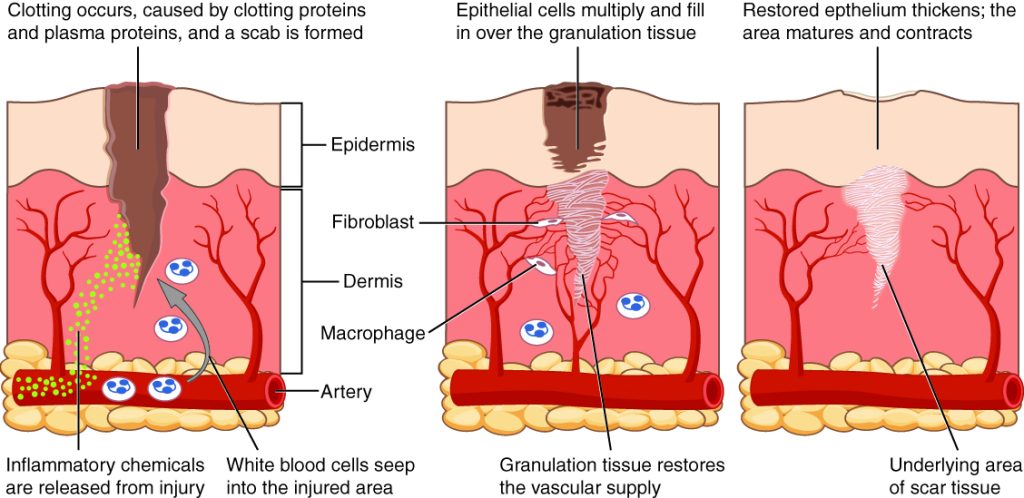

When skin is injured, there are four phases of wound healing that take place: hemostasis, inflammatory, proliferative, and maturation.[1] See Figure 20.1[2] for an illustration of the phases of wound healing.

To illustrate the phases of wound healing, imagine that you accidentally cut your finger with a knife as you were slicing an apple. Immediately after the injury occurs, blood vessels constrict, and clotting factors are activated. This is referred to as the hemostasis phase. Clotting factors form clots that stop the bleeding and act as a barrier to prevent bacterial contamination. Platelets release growth factors that alert various cells to start the repair process at the wound location. The hemostasis phase lasts up to 60 minutes, depending on the severity of the injury.[3],[4]

After the hemostasis phase, the inflammatory phase begins. Vasodilation occurs so that white blood cells in the bloodstream can move into the wound to start cleaning the wound bed. The inflammatory process appears to the observer as edema (swelling), erythema (redness), and exudate. Exudate is fluid that oozes out of a wound, also commonly called pus.[5],[6]

The proliferative phase begins within a few days after the injury and includes four important processes: epithelialization, angiogenesis, collagen formation, and contraction. Epithelialization refers to the development of new epidermis and granulation tissue. Granulation tissue is new connective tissue with new, fragile, thin-walled capillaries. Collagen is formed to provide strength and integrity to the wound. At the end of the proliferation phase, the wound begins to contract in size.[7],[8]

Capillaries begin to develop within the wound 24 hours after injury during a process called angiogenesis. These capillaries bring more oxygen and nutrients to the wound for healing. When performing dressing changes, it is essential for the nurse to protect this granulation tissue and the associated new capillaries. Healthy granulation tissue appears pink due to the new capillary formation. It is also moist, painless to the touch, and may appear “bumpy.” Conversely, unhealthy granulation tissue is dark red and painful. It bleeds easily with minimal contact and may be covered by shiny white or yellow fibrous tissue referred to as biofilm that must be removed because it impedes healing. Unhealthy granulation tissue is often caused by an infection, so wound cultures should be obtained when infection is suspected. The provider can then prescribe appropriate antibiotic treatment based on the culture results.[9]

During the maturation phase, collagen continues to be created to strengthen the wound. Collagen contributes strength to the wound to prevent it from reopening. A wound typically heals within 4-5 weeks and often leaves behind a scar. The scar tissue is initially firm, red, and slightly raised from the excess collagen deposition. Over time, the scar begins to soften, flatten, and become pale in about nine months.[10]

Types of Wound Healing

There are three types of wound healing: primary intention, secondary intention, and tertiary intention. Healing by primary intention means that the wound is sutured, stapled, glued, or otherwise closed so the wound heals beneath the closure. This type of healing occurs with clean-edged lacerations or surgical incisions, and the closed edges are referred to as approximated. See Figure 20.2[11] for an image of a surgical wound healing by primary intention.

Secondary intention occurs when the edges of a wound cannot be approximated (brought together), so the wound fills in from the bottom up by the production of granulation tissue. Examples of wounds that heal by secondary intention are pressure injuries and chainsaw injuries. Wounds that heal by secondary intention are at higher risk for infection and must be protected from contamination. See Figure 20.3[12] for an image of a wound healing by secondary intention.

Tertiary intention refers to a wound that has had to remain open or has been reopened, often due to severe infection. The wound is typically closed at a later date when infection has resolved. Wounds that heal by secondary and tertiary intention have delayed healing times and increased scar tissue.

Wound Closures

Lacerations and surgical wounds are typically closed with sutures, staples, or dermabond to facilitate healing by primary intention. See Figure 20.4[13] for an image of sutures, Figure 20.5[14] for an image of staples, and Figure 20.6[15] for an image of a wound closed with dermabond, a type of sterile surgical glue. Based on agency policy, the nurse may remove sutures and staples based on a provider order. See Figure 20.7[16] for an image of a disposable staple remover. See the checklists in the subsections later in this chapter for procedures related to surgical and staple removal.

Common Types of Wounds

There are several different types of wounds. It is important to understand different types of wounds when providing wound care because each type of wound has different characteristics and treatments. Additionally, treatments that may be helpful for one type of wound can be harmful for another type. Common types of wounds include skin tears, venous ulcers, arterial ulcers, diabetic foot wounds, and pressure injuries.[17]

Skin Tears

Skin tears are wounds caused by mechanical forces such as shear, friction, or blunt force. They typically occur in the fragile, nonelastic skin of older adults or in patients undergoing long-term corticosteroid therapy. Skin tears can be caused by the simple mechanical force used to remove an adhesive bandage or from friction as the skin brushes against a surface. Skin tears occur in the epidermis and dermis but do not extend through the subcutaneous layer. The wound bases of skin tears are typically fragile and bleed easily.[18]

Venous Ulcers

Venous ulcers are caused by lack of blood return to the heart causing pooling of fluid in the veins of the lower legs. The resulting elevated hydrostatic pressure in the veins causes fluid to seep out, macerate the skin, and cause venous ulcerations. Maceration refers to the softening and wasting away of skin due to excess fluid. Venous ulcers typically occur on the medial lower leg and have irregular edges due to the maceration. There is often a dark-colored discoloration of the lower legs, due to blood pooling and leakage of iron into the skin called hemosiderin staining. For venous ulcers to heal, compression dressings must be used, along with multilayer bandage systems, to control edema and absorb large amounts of drainage.[19] See Figure 20.8[20] for an image of a venous ulcer.

Arterial Ulcers

Arterial ulcers are caused by lack of blood flow and oxygenation to tissues. They typically occur in the distal areas of the body such as the feet, heels, and toes. Arterial ulcers have well-defined borders with a “punched out” appearance where there is a localized lack of blood flow. They are typically painful due to the lack of oxygenation to the area. The wound base may become necrotic (black) due to tissue death from ischemia. Wound dressings must maintain a moist environment, and treatment must include the removal of necrotic tissue. In severe arterial ulcers, vascular surgery may be required to reestablish blood supply to the area.[21] See Figure 20.9[22] for an image of an arterial ulcer on a patient’s foot.

Diabetic Ulcers

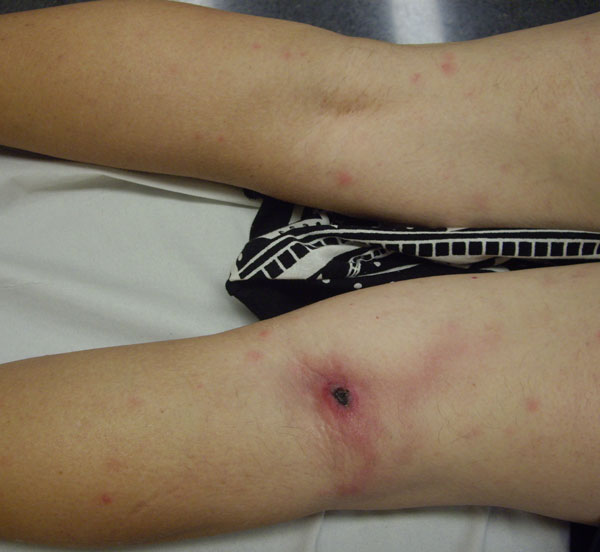

Diabetic ulcers are also called neuropathic ulcers because peripheral neuropathy is commonly present in patients with diabetes. Peripheral neuropathy is a medical condition that causes decreased sensation of pain and pressure, especially in the lower extremities. Diabetic ulcers typically develop on the plantar aspect of the feet and toes of a patient with diabetes due to lack of sensation of pressure or injury. See Figure 20.10[23] for an image of a diabetic ulcer. Wound healing is compromised in patients with diabetes due to the disease process. In addition, there is a higher risk of developing an infection that can reach the bone requiring amputation of the area. To prevent diabetic ulcers from occurring, it is vital for nurses to teach meticulous foot care to patients with diabetes and encourage the use of well-fitting shoes.[24]

Pressure Injuries

Pressure injuries are defined as “localized damage to the skin or underlying soft tissue, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of intense and prolonged pressure in combination with shear.”[25] Shear occurs when tissue layers move over the top of each other, causing blood vessels to stretch and break as they pass through the subcutaneous tissue. For example, when a patient slides down in bed, the outer skin remains immobile because it remains attached to the sheets due to friction, but deeper tissue attached to the bone moves as the patient slides down. This opposing movement of the outer layer of skin and the underlying tissues causes the capillaries to stretch and tear, which then impacts the blood flow and oxygenation of the surrounding tissues.

Braden Scale

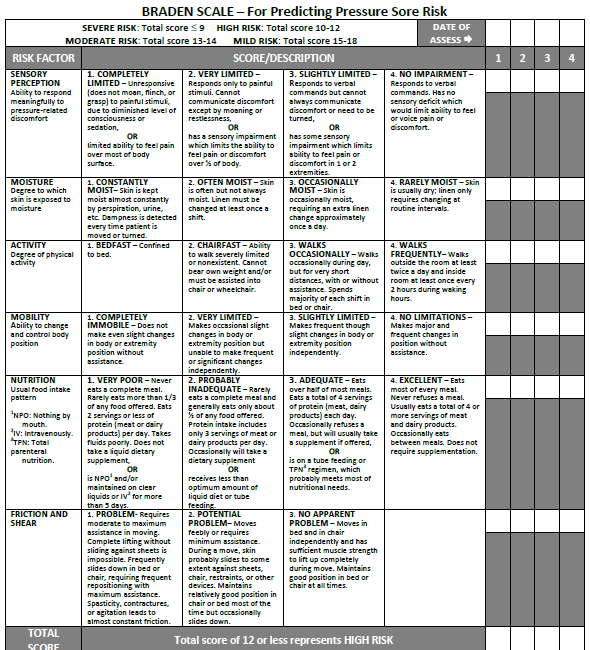

Several factors place a patient at risk for developing pressure injuries, including nutrition, mobility, sensation, and moisture. The Braden Scale is a tool commonly used in health care to provide an objective assessment of a patient’s risk for developing pressure injuries. See Figure 20.11[26] for an image of a Braden Scale. The six risk factors included on the Braden Scale are sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear, and these factors are rated on a scale from 1-4 with 1 being “completely limited” to 4 being “no impairment.” The scores from the six categories are added, and the total score indicates a patient’s risk for developing a pressure injury. A total score of 15-19 indicates mild risk, 13-14 indicates moderate risk, 10-12 indicates high risk, and less than or equal to 9 indicates severe risk. Nurses create care plans using these scores to plan interventions that prevent or treat pressure injuries.

For more information about using the Braden Scale, go to the “Integumentary” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals textbook.

Staging

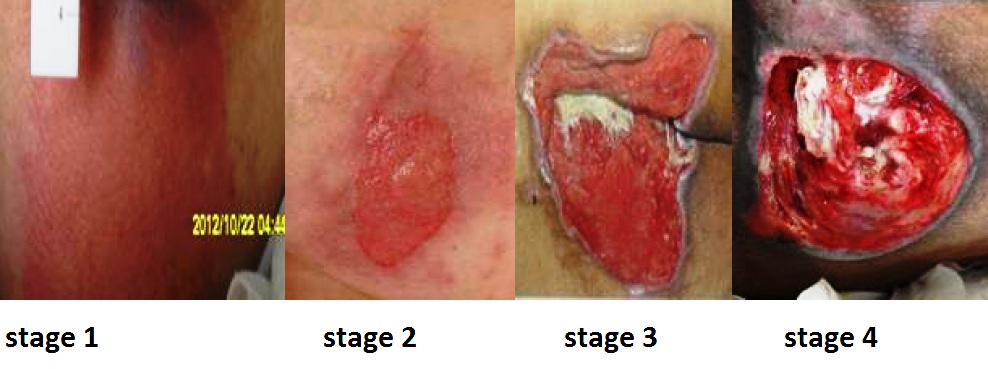

Pressure injuries commonly occur on the sacrum, heels, ischial tuberosity, and coccyx. The 2016 National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) Pressure Injury Staging System now uses the term “pressure injury” instead of pressure ulcer because an injury can occur without an ulcer present. Pressure injuries are staged from 1 through 4 based on the extent of tissue damage. For example, Stage 1 pressure injuries have reddened but intact skin, and Stage 4 pressure injuries have deep, open ulcers affecting underlying tissue and structures such as muscles, ligaments, and tendons. See Figure 20.12[27] for an image of the four stages of pressure injuries.[28] The NPUAP’s definitions of the four stages of pressure injuries are described below:

- Stage 1 pressure injuries are intact skin with a localized area of nonblanchable erythema where prolonged pressure has occurred. Nonblanchable erythema is a medical term used to describe skin redness that does not turn white when pressed.

- Stage 2 pressure injuries are partial-thickness loss of skin with exposed dermis. The wound bed is viable and may appear like an intact or ruptured blister. Stage 2 pressure injuries heal by reepithelialization and not by granulation tissue formation.[29]

- Stage 3 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss in which fat is visible, but cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, and bone are not exposed. The depth of tissue damage varies by anatomical location. Undermining and tunneling may occur in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edges becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin at the wound’s edge. Tunneling refers to passageways underneath the surface of the skin that extend from a wound and can take twists and turns. Slough and eschar may also be present in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Slough is an inflammatory exudate that is usually light yellow, soft, and moist. Eschar is dark brown/black, dry, thick, and leathery dead tissue. See Figure 20.13 [30] for an image of eschar in the center of the wound. If slough or eschar obscures the wound so that tissue loss cannot be assessed, the pressure injury is referred to as unstageable.[31] In most wounds, slough and eschar must be removed by debridement for healing to occur.

- Stage 4 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss like Stage 3 pressure injuries, but also have exposed cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, or bone. Osteomyelitis (bone infection) may be present.[32]

View a supplementary YouTube video on Pressure Injuries[33]

Factors Affecting Wound Healing

Multiple factors affect a wound’s ability to heal and are referred to as local and systemic factors. Local factors refer to factors that directly affect the wound, whereas systemic factors refer to the overall health of the patient and their ability to heal. Local factors include localized blood flow and oxygenation of the tissue, the presence of infection or a foreign body, and venous sufficiency. Venous insufficiency is a medical condition where the veins in the legs do not adequately send blood back to the heart, resulting in a pooling of fluids in the legs.[34]

Systemic factors that affect a patient’s ability to heal include nutrition, mobility, stress, diabetes, age, obesity, medications, alcohol use, and smoking.[35] When a nurse is caring for a patient with a wound that is not healing as anticipated, it is important to further assess for the potential impact of these factors:

- Nutrition. Nutritional deficiencies can have a profound impact on healing and must be addressed for chronic wounds to heal. Protein is one of the most important nutritional factors affecting wound healing. For example, in patients with pressure injuries, 30 to 35 kcal/kg of calorie intake with 1.25 to 1.5g/kg of protein and micronutrients supplementation is recommended daily.[36] In addition, vitamin C and zinc deficiency have many roles in wound healing. It is important to collaborate with a dietician to identify and manage nutritional deficiencies when a patient is experiencing poor wound healing.[37]

- Stress. Stress causes an impaired immune response that results in delayed wound healing. Although a patient cannot necessarily control the amount of stress in their life, it is possible to control one’s reaction to stress with healthy coping mechanisms. The nurse can help educate the patient about healthy coping strategies.

- Diabetes. Diabetes causes delayed wound healing due to many factors such as neuropathy, atherosclerosis (a buildup of plaque that obstructs blood flow in the arteries resulting in decreased oxygenation of tissues), a decreased host immune resistance, and increased risk for infection.[38] Read more about neuropathy and diabetic ulcers under the “Common Types of Wounds” subsection. Nurses provide vital patient education to patients with diabetes to effectively manage the disease process for improved wound healing.

- Age. Older adults have an altered inflammatory response that can impair wound healing. Nurses can educate patients about the importance of exercise for improved wound healing in older adults.[39]

- Obesity. Obese individuals frequently have wound complications, including infection, dehiscence, hematoma formation, pressure injuries, and venous injuries. Nurses can educate patients about healthy lifestyle choices to reduce obesity in patients with chronic wounds.[40]

- Medications. Medications such as corticosteroids impair wound healing due to reduced formation of granulation tissue.[41] When assessing a chronic wound that is not healing as expected, it is important to consider the side effects of the patient’s medications.

- Alcohol consumption. Research shows that exposure to alcohol impairs wound healing and increases the incidence of infection.[42] Patients with impaired healing of chronic wounds should be educated to avoid alcohol consumption.

- Smoking. Smoking impacts the inflammatory phase of the wound healing process, resulting in poor wound healing and an increased risk of infection.[43] Patients who smoke should be encouraged to stop smoking.

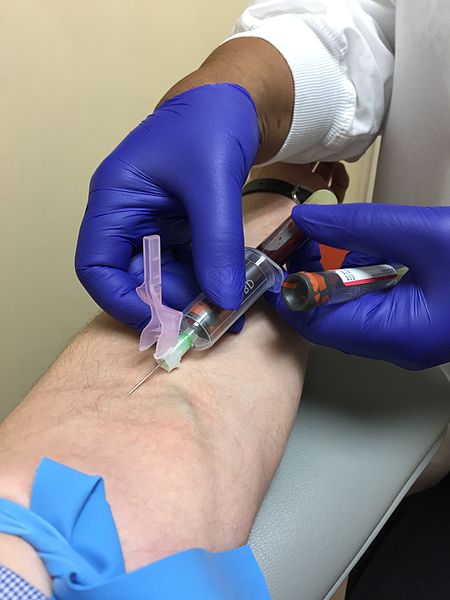

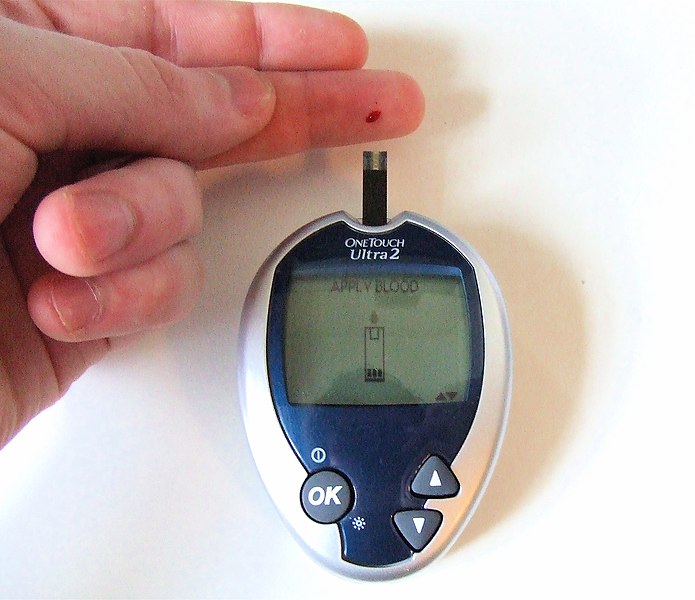

Lab Values Affecting Wound Healing

When a chronic wound is not healing as expected, laboratory test results may provide additional clues regarding the causes of the delayed healing. See Table 20.2 for lab results that offer clues to systemic issues causing delayed wound healing.[44]

Table 20.2 Lab Values Associated with Delayed Wound Healing[45]

| Abnormal Lab Value | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Low hemoglobin | Low hemoglobin indicates less oxygen is transported to the wound site. |

| Elevated white blood cells (WBC) | Increased WBC indicates infection is occurring. |

| Low platelets | Platelets are important during the proliferative phase in the creation of granulation tissue and angiogenesis.[46] |

| Low albumin | Low albumin indicates decreased protein levels. Protein is required for effective wound healing. |

| Elevated blood glucose or hemoglobin A1C | Elevated blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C levels indicate poor management of diabetes mellitus, a disease that impacts wound healing. |

| Elevated serum BUN and creatinine | BUN and creatinine levels are indicators of kidney function, with elevated levels indicating worsening kidney function. Elevated BUN (blood urea nitrogen) levels impact wound healing. |

| Positive wound culture | Positive wound cultures indicate an infection is present and provide additional information, including the type and number of bacteria present, as well as identifying antibiotics to which the bacteria is susceptible. The nurse reviews this information when administering antibiotics to ensure the prescribed therapy is effective for the type of bacteria present. |

Wound Complications

In addition to delayed wound healing, several other complications can occur. Three common complications are the development of a hematoma, infection, or dehiscence. These complications should be immediately reported to the health care provider.

Hematoma

A hematoma is an area of blood that collects outside of the larger blood vessels. A hematoma is more severe than ecchymosis (bruising) that occurs when small veins and capillaries under the skin break. The development of a hematoma at a surgical site can lead to infection and incisional dehiscence.[47] See Figure 20.14[48] for an image of a hematoma.

Infection

A break in the skin allows bacteria to enter and begin to multiply. Microbial contamination of wounds can progress from localized infection to systemic infection, sepsis, and subsequent life- and limb-threatening infection. Signs of a localized wound infection include redness, warmth, and tenderness around the wound. Purulent or malodorous drainage may also be present. Signs that a systemic infection is developing and requires urgent medical management include the following[49]:

- Fever over 101 F (38 C)

- Overall malaise (lack of energy and not feeling well)

- Change in level of consciousness/increased confusion

- Increasing or continual pain in the wound

- Expanding redness or swelling around the wound

- Loss of movement or function of the wounded area

Dehiscence

Dehiscence refers to the separation of the edges of a surgical wound. A dehisced wound can appear fully open where the tissue underneath is visible, or it can be partial where just a portion of the wound has torn open. Wound dehiscence is always a risk in a surgical wound, but the risk increases if the patient is obese, smokes, or has other health conditions, such as diabetes, that impact wound healing. Additionally, the location of the wound and the amount of physical activity in that area also increase the chances of wound dehiscence.[50] See Figure 20.15[51] for an image of dehiscence in an abdominal surgical wound in a 50-year-old obese female with a history of smoking and malnutrition.

Wound dehiscence can occur suddenly, especially in abdominal wounds when the patient is coughing or straining. Evisceration is a rare but severe surgical complication when dehiscence occurs, and the abdominal organs protrude out of the incision. Signs of impending dehiscence include redness around the wound margins and increasing drainage from the incision. The wound will also likely become increasingly painful. Suture breakage can be a sign that the wound has minor dehiscence or is about to dehisce.[52]

To prevent wound dehiscence, surgical patients must follow all post-op instructions carefully. The patient must move carefully and protect the skin from being pulled around the wound site. They should also avoid tensing the muscles surrounding the wound and avoid heavy lifting as advised.[53]

Media Attributions

- 417_Tissue_Repair

- Ventriculoperitoneal_shunt_-_surgical_wound_healing_-_belly_-_day_12

- Atrophied_skin

- Wound_closed_with_surgical_sutures

- Surgical_staples1

- Incision_wound_on_child’s_arm,_closed_with_Dermabond

- 24503995344_82cc1c6bcd_o

- Úlceras_antes_da_cirurgia

- Arterial_ulcer_peripheral_vascular_disease

- Diabetic_Planta_ulcer

- braden_Scale

- Wound_stage

- Inoculation_eschar_Rickettsia_sibirica_mongolitimonae_infection

- 3109068066_debefe26fd_o

- Bogota_bag

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “417 Tissue Repair.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Grubbs and Mannah and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Grubbs and Mannah and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Grubbs and Mannah and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Alhajj, Bansal, and Goyal and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Grubbs and Mannah and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Ventriculoperitoneal shunt - surgical wound healing - belly - day 12.jpg” by Hansmuller is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Atrophied skin.png” by sansea2 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Wound closed with surgical sutures.jpg” by Wikip2011 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Surgical staples1.jpg” by Llywrch is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5 ↵

- “Incision wound on child's arm, closed with Dermabond.jpg” by ragesoss is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Not quite scissors - TROML - 1366” by Clint Budd is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Cox, J. (2019). Wound care 101. Nursing, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000580632.58318.08 ↵

- Cox, J. (2019). Wound care 101. Nursing, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000580632.58318.08 ↵

- Cox, J. (2019). Wound care 101. Nursing, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000580632.58318.08 ↵

- “Úlceras_antes_da_cirurgia.JPG” by Nini00 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Cox, J. (2019). Wound care 101. Nursing, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000580632.58318.08 ↵

- “Arterial ulcer peripheral vascular disease.jpg” by Jonathan Moore is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Diabetic Planta ulcer.jpg” by Dr. Lorimer is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Cox, J. (2019). Wound care 101. Nursing, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000580632.58318.08 ↵

- Edsberg, L. E., Black, J. M., Goldberg, M., McNichol, L., Moore, L., & Sieggreen, M. (2016). Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised pressure injury staging system. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing: Official Publication of The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 43(6), 585–597. https://journals.lww.com/jwocnonline/Fulltext/2016/11000/Revised_National_Pressure_Ulcer_Advisory_Panel.3.aspx ↵

- The Braden Scale, from Prevention Plus, is included on the basis of Fair Use. ↵

- “Wound stage.jpg” by Babagolzadeh is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Edsberg, L. E., Black, J. M., Goldberg, M., McNichol, L., Moore, L., & Sieggreen, M. (2016). Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised pressure injury staging system. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing: Official Publication of The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 43(6), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0000000000000281 ↵

- Edsberg, L. E., Black, J. M., Goldberg, M., McNichol, L., Moore, L., & Sieggreen, M. (2016). Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised pressure injury staging system. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing: Official Publication of The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 43(6), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0000000000000281 ↵

- "Inoculation_eschar_Rickettsia_sibirica_mongolitimonae_infection.jpg" by José M. Ramos, Isabel Jado, Sergio Padilla, Mar Masiá, Pedro Anda, and Félix Gutiérrez is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Edsberg, L. E., Black, J. M., Goldberg, M., McNichol, L., Moore, L., & Sieggreen, M. (2016). Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised pressure injury staging system. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing: Official Publication of The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 43(6), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0000000000000281 ↵

- Edsberg, L. E., Black, J. M., Goldberg, M., McNichol, L., Moore, L., & Sieggreen, M. (2016). Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised pressure injury staging system. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing: Official Publication of The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 43(6), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0000000000000281 ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2018, March 7). Pressure ulcers (injuries) stages, prevention, assessment | Stage 1, 2, 3, 4 unstageable NCLEX [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/MDtPik1UE6k ↵

- Guo, S., & Dipietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125 ↵

- Guo, S., & Dipietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125 ↵

- Cox, J. (2019). Wound care 101. Nursing, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000580632.58318.08 ↵

- Guo, S., & Dipietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125 ↵

- Guo, S., & Dipietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125 ↵

- Guo, S., & Dipietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125 ↵

- Guo, S., & Dipietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125 ↵

- Guo, S., & Dipietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125 ↵

- Guo, S., & Dipietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125 ↵

- Guo, S., & Dipietro, L. A. (2010). Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research, 89(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509359125 ↵

- Grey, J. E., Enoch, S., & Harding, K. G. (2006). Wound assessment. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 332(7536), 285–288. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7536.285 ↵

- Grey, J. E., Enoch, S., & Harding, K. G. (2006). Wound assessment. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 332(7536), 285–288. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7536.285 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Grubbs and Mannah is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Edsberg, L. E., Black, J. M., Goldberg, M., McNichol, L., Moore, L., & Sieggreen, M. (2016). Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised pressure injury staging system. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing: Official Publication of The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, 43(6), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1097/won.0000000000000281 ↵

- “Ankle swell and internal bleeding” by Glen Bowman is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 ↵

- WoundSource. (2016, October 19). 8 signs of wound infection. https://www.woundsource.com/blog/8-signs-wound-infection ↵

- WoundSource. (2018, March 28). Complications in chronic wound healing and associated interventions. https://www.woundsource.com/blog/complications-in-chronic-wound-healing-and-associated-interventions ↵

- “Bogota bag.png” by Suarez-Grau, J. M., Guadalajara Jurado, J. F., Gómez Menchero, J., Bellido Luque, J. A. is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- WoundSource. (2018, March 28). Complications in chronic wound healing and associated interventions. https://www.woundsource.com/blog/complications-in-chronic-wound-healing-and-associated-interventions ↵

- WoundSource. (2018, March 28). Complications in chronic wound healing and associated interventions. https://www.woundsource.com/blog/complications-in-chronic-wound-healing-and-associated-interventions ↵

Before discussing specific procedures related to facilitating bowel and bladder function, let’s review basic concepts related to urinary and bowel elimination. When facilitating alternative methods of elimination, it is important to understand the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal and urinary systems, as well as the adverse effects of various conditions and medications on elimination. Use the information below to review information about these topics.

For more information about the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal system and medications used to treat diarrhea and constipation, visit the "Gastrointestinal" chapter of the Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook.

For more information about the anatomy and physiology of the kidneys and diuretic medications used to treat fluid overload, visit the "Cardiovascular and Renal System" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook.

For more information about applying the nursing process to facilitate elimination, visit the "Elimination" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Urinary Elimination Devices

This section will focus on the devices used to facilitate urinary elimination. Urinary catheterization is the insertion of a catheter tube into the urethral opening and placing it in the neck of the urinary bladder to drain urine. There are several types of urinary elimination devices, such as indwelling catheters, intermittent catheters, suprapubic catheters, and external devices. Each of these types of devices is described in the following subsections.

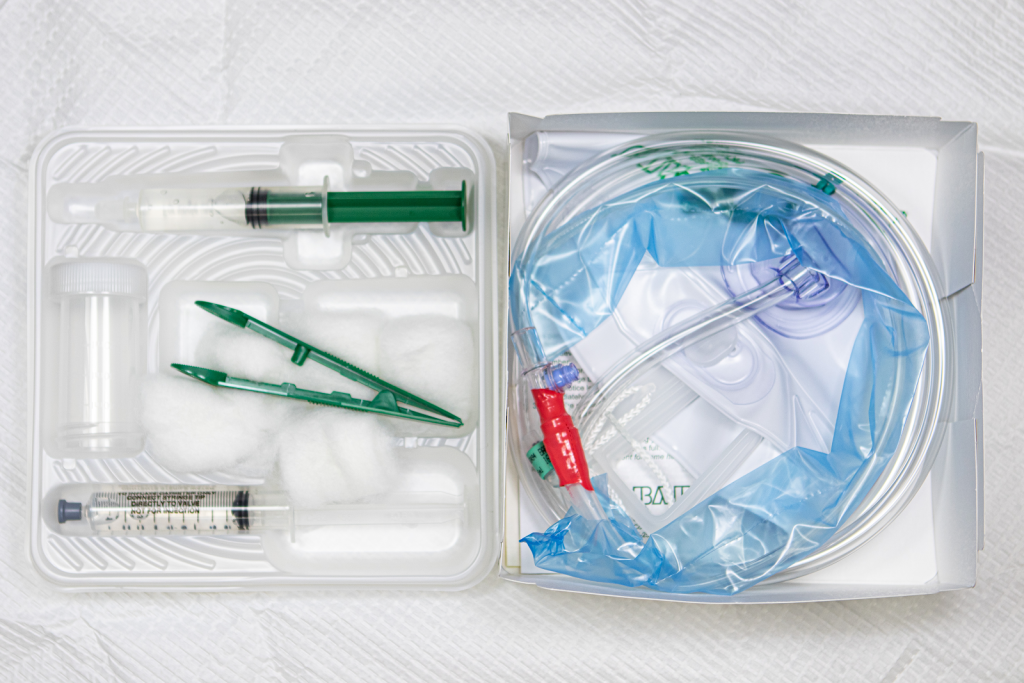

Indwelling Catheter

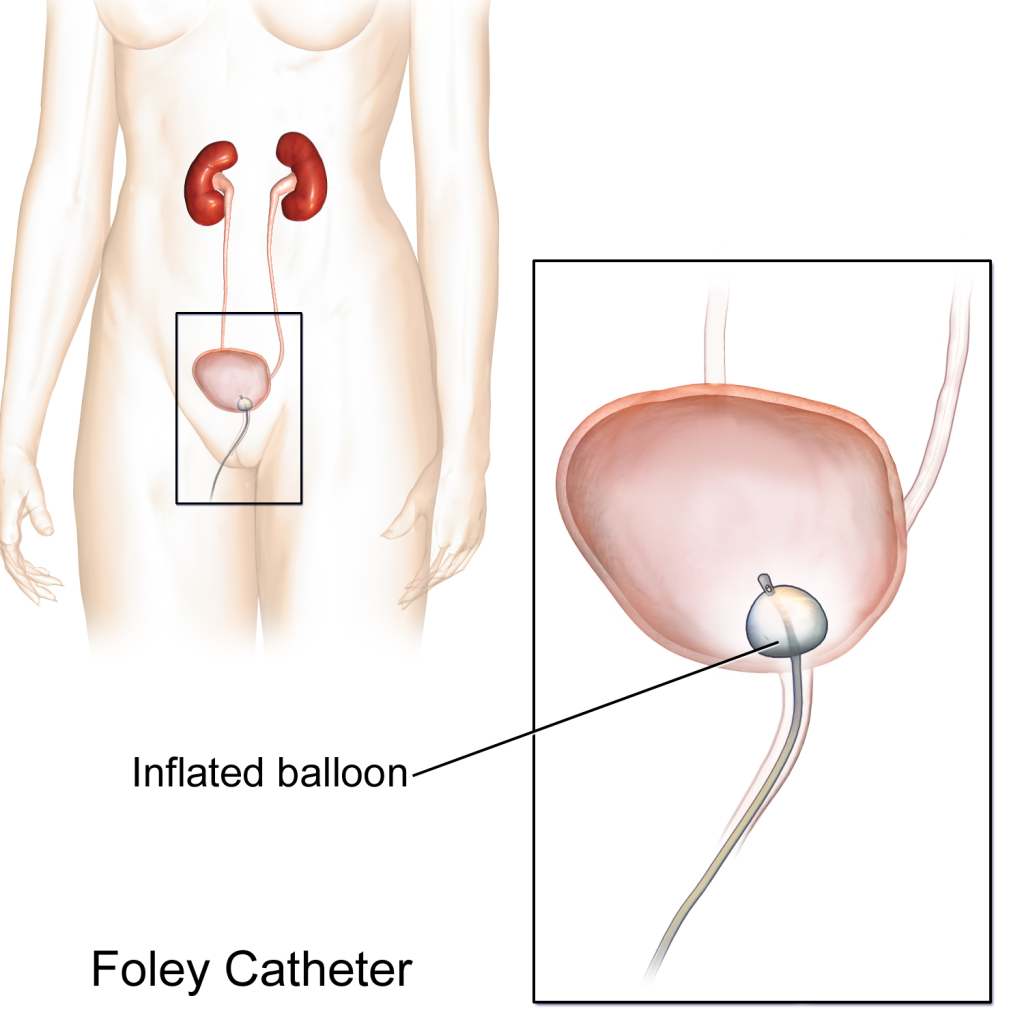

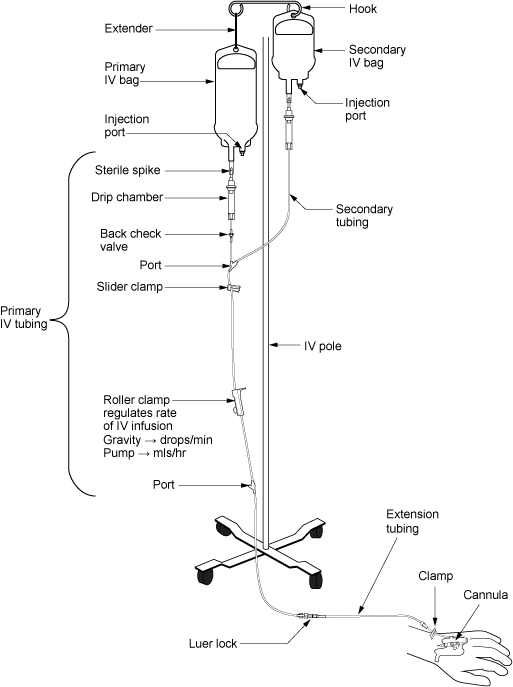

An indwelling catheter, often referred to as a “Foley catheter,” refers to a urinary catheter that remains in place after insertion into the bladder for the continual collection of urine. It has a balloon on the insertion tip to maintain placement in the neck of the bladder. The other end of the catheter is attached to a drainage bag for the collection of urine. See Figure 21.1[1] for an illustration of the anatomical placement of an indwelling catheter in the bladder neck.

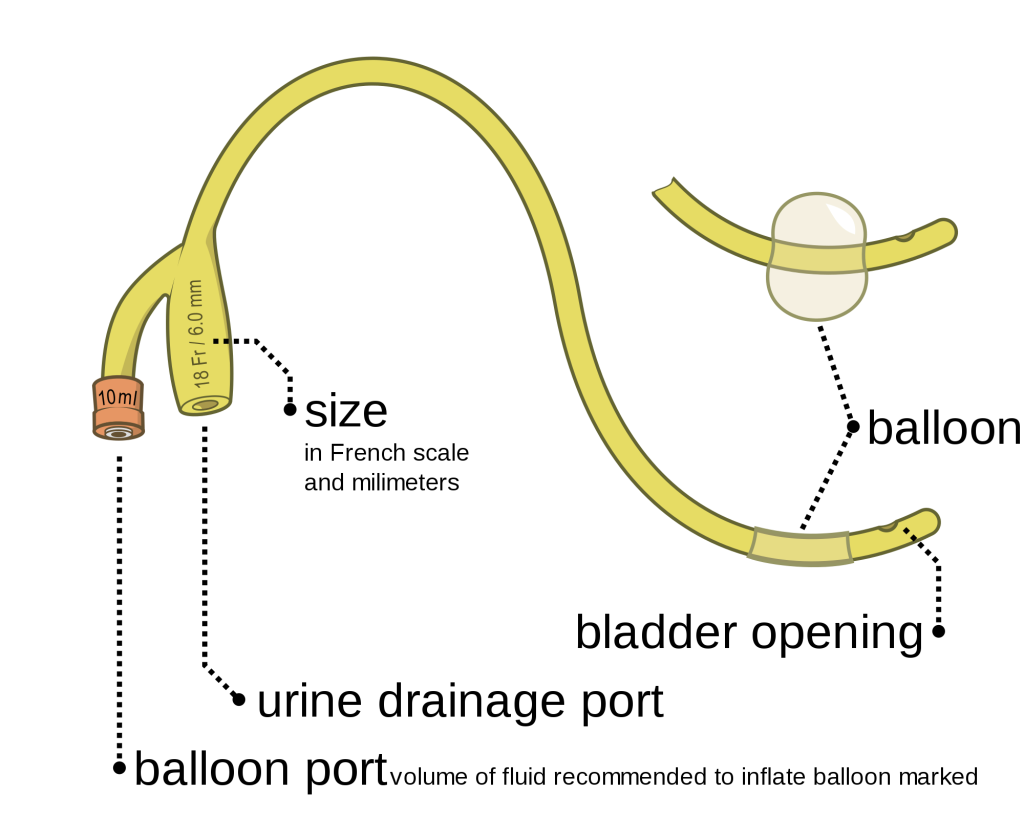

The distal end of an indwelling catheter has a urine drainage port that is connected to a drainage bag. The size of the catheter is marked at this end using the French catheter scale. A balloon port is also located at this end, where a syringe is inserted to inflate the balloon after it is inserted into the bladder. The balloon port is marked with the amount of fluid required to fill the balloon. See Figure 21.2[2] for an image of the parts of an indwelling catheter.

Catheters have different sizes, with the larger the number indicating a larger diameter of the catheter. See Figure 21.3[3] for an image of the French catheter scale.

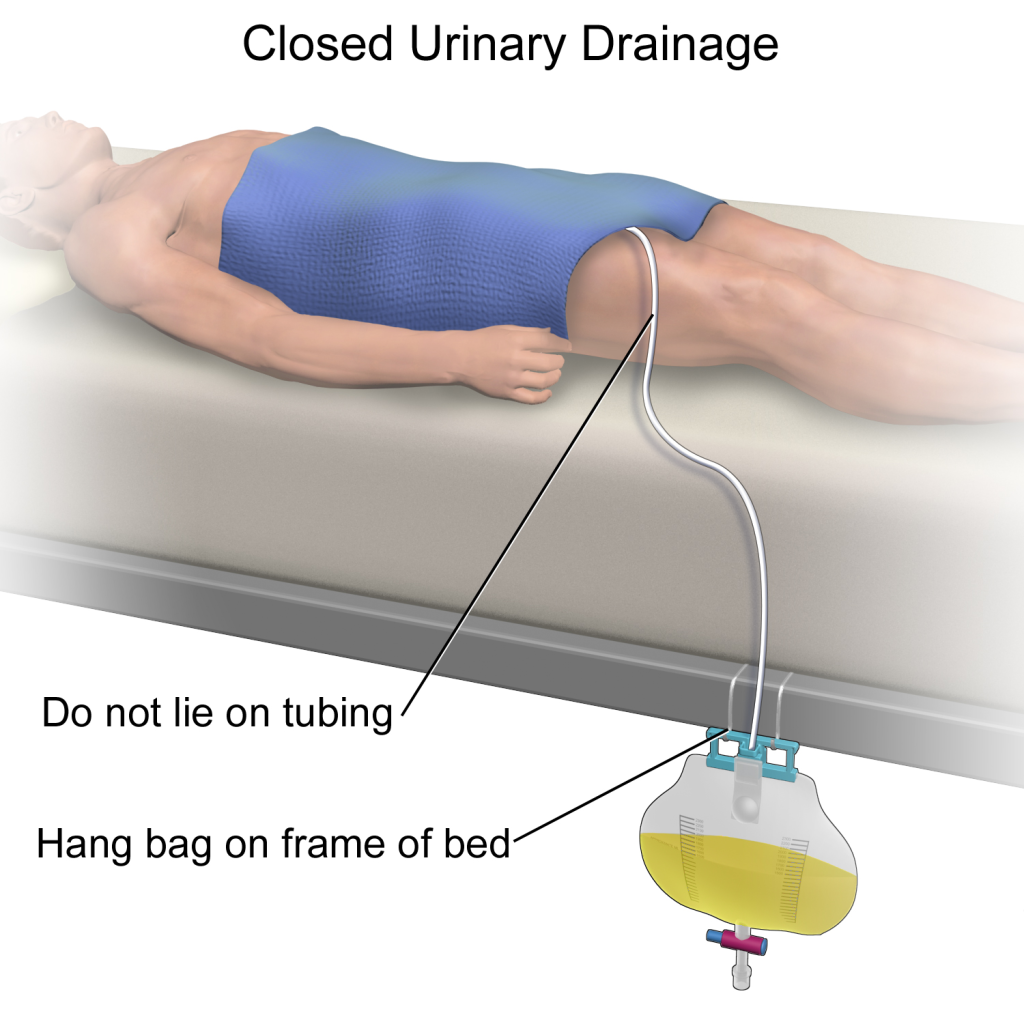

There are two common types of bags that may be attached to an indwelling catheter. During inpatient or long-term care, larger collection bags that can hold up to two liters of fluid are used. See Figure 21.4[4] for an image of a typical collection bag attached to an indwelling catheter. These bags should be emptied when they are half to two-thirds full to prevent traction on the urethra from the bag. Additionally, the collection bag should always be placed below the level of the patient’s bladder so that urine flows out of the bladder and urine does not inadvertently flow back into the bladder. Ensure the tubing is not coiled, kinked, or compressed so that urine can flow unobstructed into the bag. Slack should be maintained in the tubing to prevent injury to the patient's urethra. To prevent the development of a urinary tract infection, the bag should not be permitted to touch the floor.

See Figure 21.5[5] for an illustration of the placement of the urine collection bag when the patient is lying in bed.

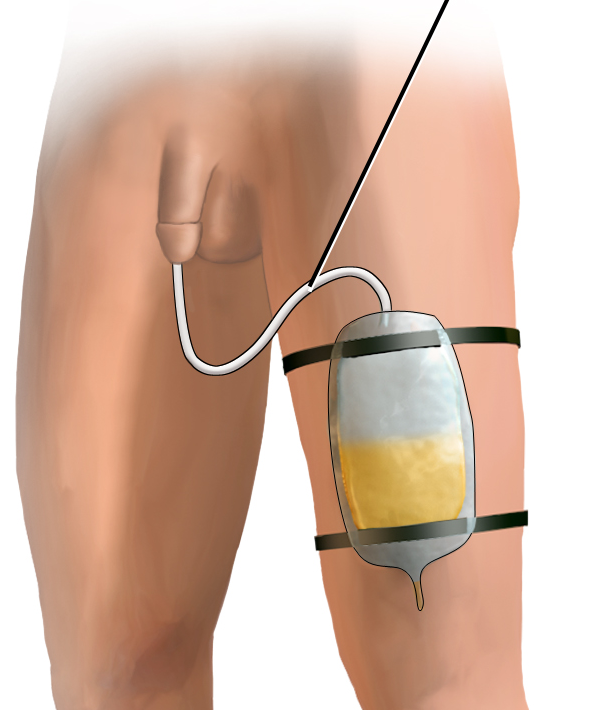

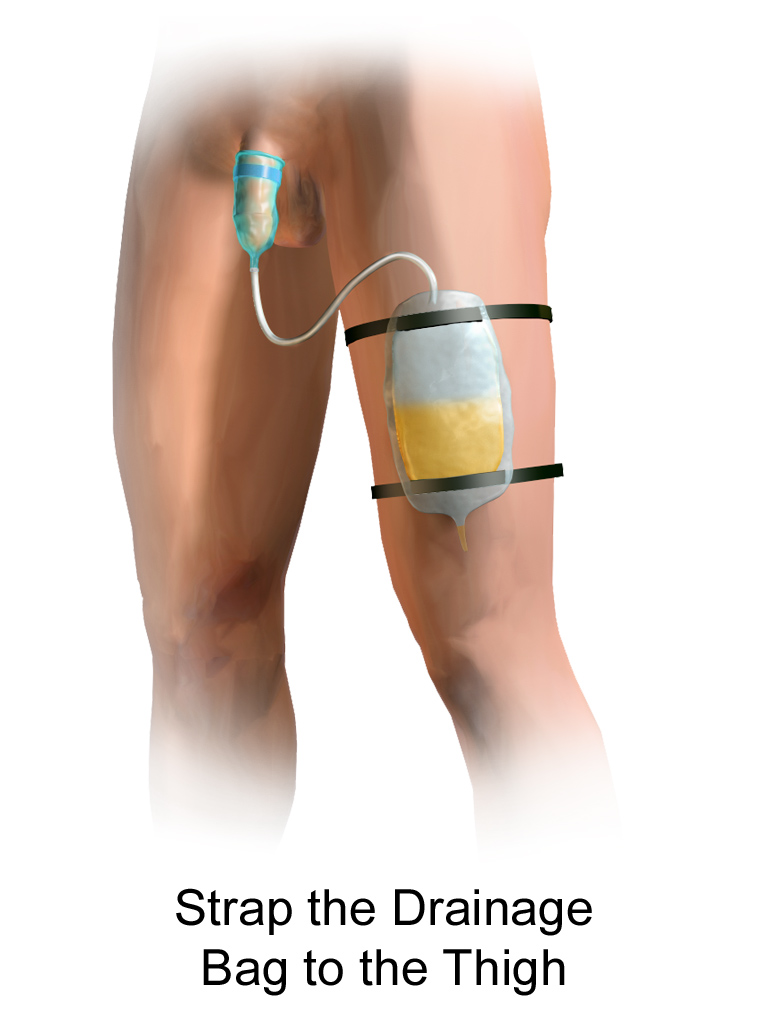

A second type of urine collection bag is a leg bag. Leg bags provide discretion when the patient is in public because they can be worn under clothing. However, leg bags are small and must be emptied more frequently than those used during inpatient care. Figure 21.6[6] for an image of leg bag and Figure 21.7[7] for an illustration of an indwelling catheter attached to a leg bag.

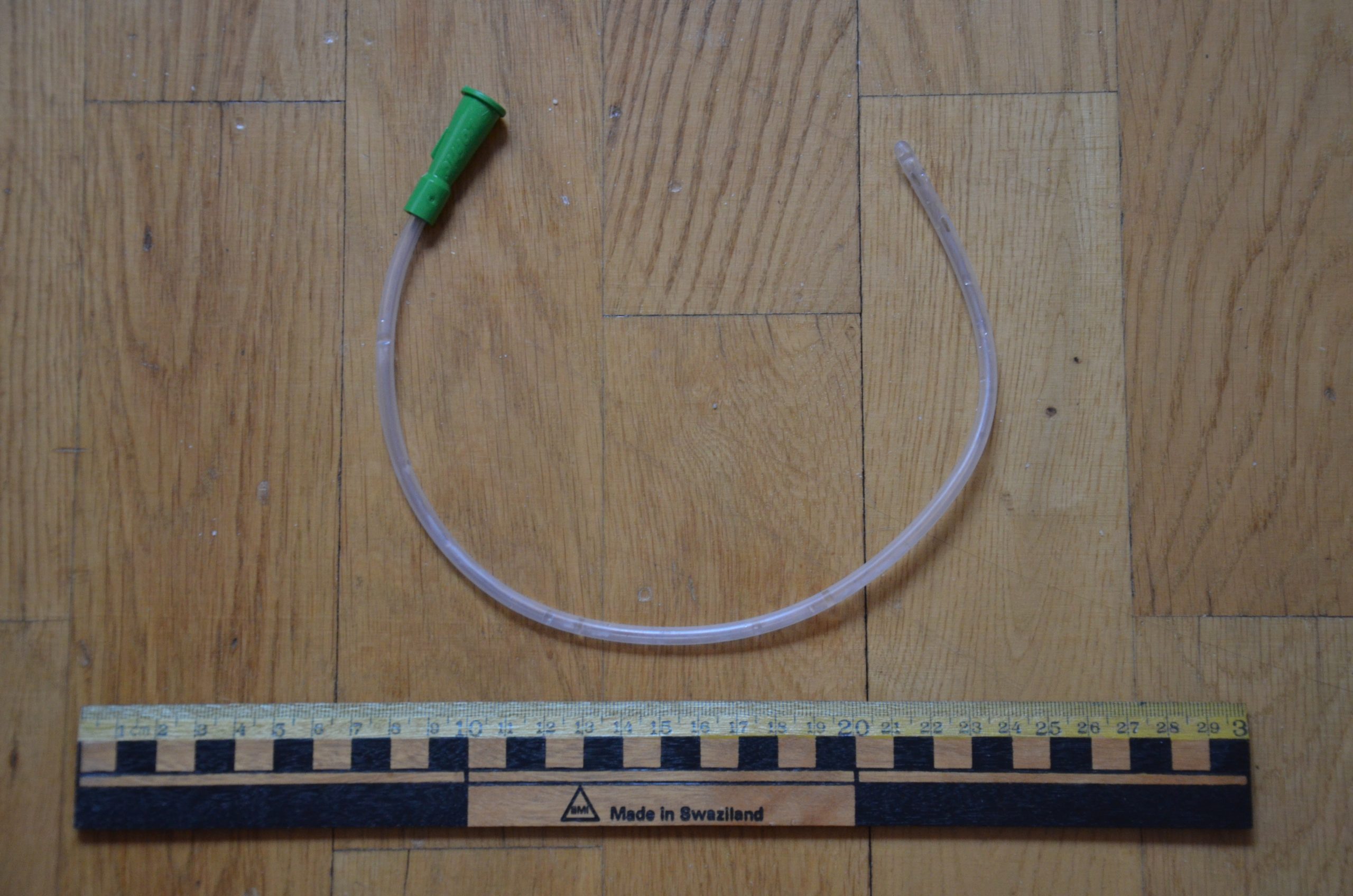

Straight Catheter

A straight catheter is used for intermittent urinary catheterization. The catheter is inserted to allow for the flow of urine and then immediately removed, so a balloon is not required at the insertion tip. See Figure 21.8[8] for an image of a straight catheter. Intermittent catheterization is used for the relief of urinary retention. It may be performed once, such as after surgery when a patient is experiencing urinary retention due to the effects of anesthesia, or performed several times a day to manage chronic urinary retention. Some patients may also independently perform self-catheterization at home to manage chronic urinary retention caused by various medical conditions. In some situations, a straight catheter is also used to obtain a sterile urine specimen for culture when a patient is unable to void into a sterile specimen cup. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), intermittent catheterization is preferred to indwelling urethral catheters whenever feasible because of decreased risk of developing a urinary tract infection.[9]

Other Types of Urinary Catheters

Coude Catheter Tip

Coude catheter tips are curved to follow the natural curve of the urethra during catheterization. They are often used when catheterizing male patients with enlarged prostate glands. See Figure 21.9[10] for an example of a urinary catheter with a coude tip. During insertion, the tip of the coude catheter must be pointed anteriorly or it can cause damage to the urethra. A thin line embedded in the catheter provides information regarding orientation during the procedure; maintain the line upwards to keep it pointed anteriorly.

Irrigation Catheter

Irrigation catheters are typically used after prostate surgery to flush the surgical area. These catheters are larger in size to allow for irrigation of the bladder to help prevent the formation of blood clots and to flush them out. See Figure 21.10[11] for an image comparing a larger 20 French catheter (typically used for irrigation) to a 14 French catheter (typically used for indwelling catheters).

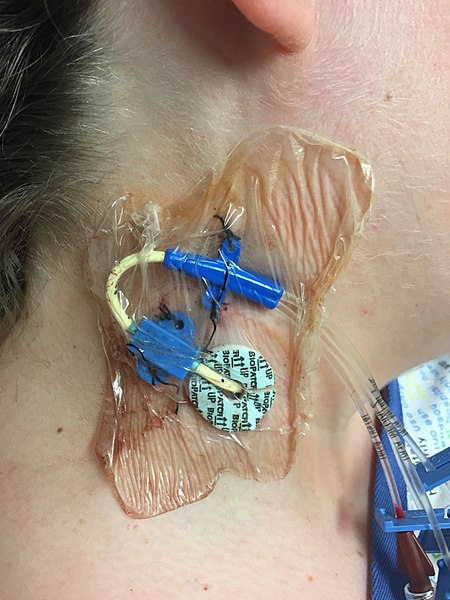

Suprapubic Catheters

Suprapubic catheters are surgically inserted through the abdominal wall into the bladder. This type of catheter is typically inserted when there is a blockage within the urethra that does not allow the use of a straight or indwelling catheter. Suprapubic catheters may be used for a short period of time for acute medical conditions or may be used permanently for chronic conditions. See Figure 21.11[12] for an image of a suprapubic catheter. The insertion site of a suprapubic catheter must be cleaned regularly according to agency policy with appropriate steps to prevent skin breakdown.

Male Condom Catheter

A condom catheter is a noninvasive device used for males with incontinence. It is placed over the penis and connected to a drainage bag. This device protects and promotes healing of the skin around the perineal area and inner legs and is used as an alternative to an indwelling urinary catheter. See Figure 21.12[13] for an image of a condom catheter and Figure 21.13[14] for an illustration of a condom catheter attached to a leg bag.

Female External Urinary Catheter

Female external urinary catheters (FEUC) have been recently introduced into practice to reduce the incidence of catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) in women.[15] The external female catheter device is made of a purewick material that is placed externally over the female’s urinary meatus. The wicking material is attached to a tube that is hooked to a low-suction device. When the wick becomes saturated with urine, it is suctioned into a drainage canister. Preliminary studies have found that utilizing the FEUC device reduced the risk for CAUTI.[16],[17]

View these supplementary YouTube videos on female external urinary catheters:

Students demonstrate use of PureWick female external catheter[18]

How to use the use the PureWick - a female external catheter[19]

Safely and accurately placing an indwelling urinary catheter poses several challenges that require the nurse to use clinical judgment. Challenges can include anatomical variations in a specific patient, medical conditions affecting patient positioning, and maintaining sterility of the procedure with confused or agitated patients. See the checklists on Foley Catheter Insertion (Male) and Foley Catheter Insertion (Female) for detailed instructions.

Nursing interventions to prevent the development of a catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) on insertion include the following[20]:

- Determine if insertion of an indwelling catheter meets CDC guidelines.

- Select the smallest-sized catheter that is appropriate for the patient, typically a 14 French.

- Obtain assistance as needed to facilitate patient positioning, visualization, and insertion. Many agencies require two nurses for the insertion of indwelling catheters.

- Perform perineal care before inserting a urinary catheter and regularly thereafter.

- Perform hand hygiene before and after insertion, as well as during any manipulation of the device or site.

- Maintain strict aseptic technique during insertion and use sterile gloves and equipment.

- Inflate the balloon after insertion per manufacturer instructions. It is not recommended to preinflate the balloon prior to insertion.

- Properly secure the catheter after insertion to prevent tissue damage.

- Keep the drainage bag below the bladder but not resting on the floor.

- Check the system to ensure there are no kinks or obstructions to urine flow.

- Provide routine hygiene of the urinary meatus during daily bathing and cleanse the perineal area after every bowel movement. In uncircumcised males, gently retract the foreskin, cleanse the meatus, and then return the foreskin to the original position. Do not cleanse the periurethral area with antiseptics after the catheter is in place.[21] To avoid contaminating the urinary tract, always clean by wiping away from the urinary meatus.

- Empty the collection bag regularly using a separate, clean collecting container for each patient. Avoid splashing and prevent contact of the drainage spigot with the nonsterile collecting container or other surfaces. Never allow the bag to touch the floor.[22],[23]

Video Review of Thompson Rivers University's Urinary Catheterization:

Swelling in tissues caused by fluid retention.

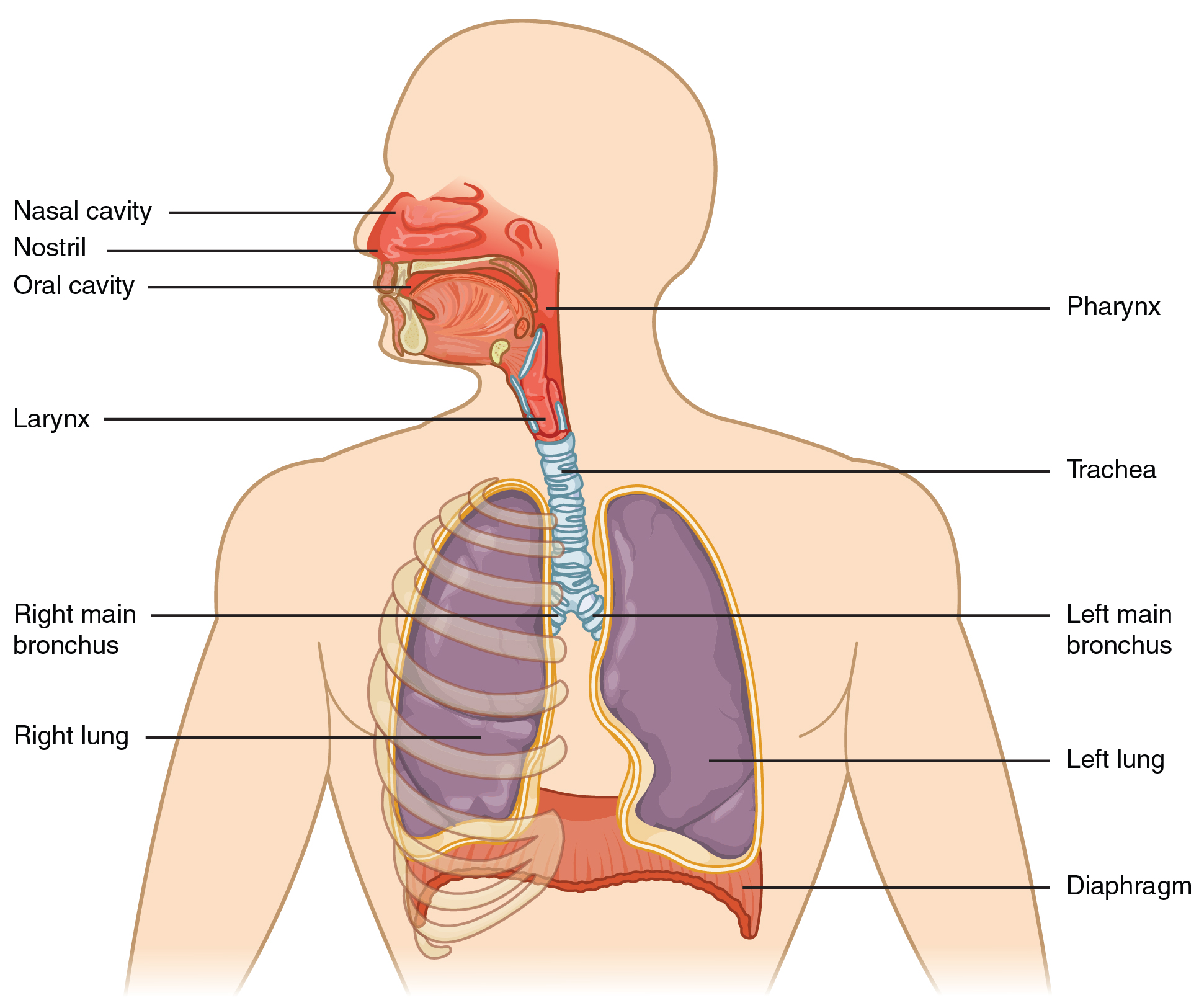

With an understanding of the basic structures and primary functions of the respiratory system, the nurse collects subjective and objective data to perform a focused respiratory assessment.

Subjective Assessment

Collect data using interview questions, paying particular attention to what the patient is reporting. The interview should include questions regarding any current and past history of respiratory health conditions or illnesses, medications, and reported symptoms. Consider the patient’s age, gender, family history, race, culture, environmental factors, and current health practices when gathering subjective data. The information discovered during the interview process guides the physical exam and subsequent patient education. See Table 10.3a for sample interview questions to use during a focused respiratory assessment.[26]

Table 10.3a Interview Questions for Subjective Assessment of the Respiratory System

| Interview Questions | Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a respiratory condition, such as asthma, COPD, pneumonia, or allergies?

Do you use oxygen or peak flow meter? Do you use home respiratory equipment like CPAP, BiPAP, or nebulizer devices? |

Please describe the conditions and treatments. |

| Are you currently taking any medications, herbs, or supplements for respiratory concerns? | Please identify what you are taking and the purpose of each. |

| Have you had any feelings of breathlessness

(dyspnea)? |

Note: If the shortness of breath is severe or associated with chest pain, discontinue the interview and obtain emergency assistance.

Are you having any shortness of breath now? If yes, please rate the shortness of breath from 0-10 with "0" being none and "10" being severe? Does anything bring on the shortness of breath (such as activity, animals, food, or dust)? If activity causes the shortness of breath, how much exertion is required to bring on the shortness of breath? When did the shortness of breath start? Is the shortness of breath associated with chest pain or discomfort? How long does the shortness of breath last? What makes the shortness of breath go away? Is the shortness of breath related to a position, like lying down? Do you sleep in a recliner or upright in bed? Do you wake up at night feeling short of breath? How many pillows do you sleep on? How does the shortness of breath affect your daily activities? |

| Do you have a cough? | When you cough, do you bring up anything? What color is the phlegm?

Do you cough up any blood (hemoptysis)? Do you have any associated symptoms with the cough such as fever, chills, or night sweats? How long have you had the cough? Does anything bring on the cough (such as activity, dust, animals, or change in position)? What have you used to treat the cough? Has it been effective? |

| Do you smoke or vape? | What products do you smoke/vape? If cigarettes are smoked, how many packs a day do you smoke?

How long have you smoked/vaped? Have you ever tried to quit smoking/vaping? What strategies gave you the best success? Are you interested in quitting smoking/vaping? If the patient is ready to quit, the five successful interventions are the "5 A's": Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange. Ask - Identify and document smoking status for every patient at every visit. Advise - In a clear, strong, and personalized manner, urge every user to quit. Assess - Is the user willing to make a quitting attempt at this time? Assist - For the patient willing to make a quitting attempt, use counseling and pharmacotherapy to help them quit. Arrange - Schedule follow-up contact, in person or by telephone, preferably within the first week after the quit date.[27] |

Life Span Considerations

Depending on the age and capability of the child, subjective data may also need to be retrieved from a parent and/or legal guardian.

Pediatric

- Is your child up-to-date with recommended immunizations?

- Is your child experiencing any cold symptoms (such as runny nose, cough, or nasal congestion)?

- How is your child’s appetite? Is there any decrease or change recently in appetite or wet diapers?

- Does your child have any hospitalization history related to respiratory illness?

- Did your child have any history of frequent ear infections as an infant?

Older Adult

- Have you noticed a change in your breathing?

- Do you get short of breath with activities that you did not before?

- Can you describe your energy level? Is there any change from previous?

Objective Assessment

A focused respiratory objective assessment includes interpretation of vital signs; inspection of the patient’s breathing pattern, skin color, and respiratory status; palpation to identify abnormalities; and auscultation of lung sounds using a stethoscope. For more information regarding interpreting vital signs, see the “General Survey” chapter. The nurse must have an understanding of what is expected for the patient’s age, gender, development, race, culture, environmental factors, and current health condition to determine the meaning of the data that is being collected.

Evaluate Vital Signs

The vital signs may be taken by the nurse or delegated to unlicensed assistive personnel such as a nursing assistant or medical assistant. Evaluate the respiratory rate and pulse oximetry readings to verify the patient is stable before proceeding with the physical exam. The normal range of a respiratory rate for an adult is 12-20 breaths per minute at rest, and the normal range for oxygen saturation of the blood is 94–98% (SpO₂).[28] Bradypnea is less than 12 breaths per minute, and tachypnea is greater than 20 breaths per minute.

Inspection

Inspection during a focused respiratory assessment includes observation of level of consciousness, breathing rate, pattern and effort, skin color, chest configuration, and symmetry of expansion.

- Assess the level of consciousness. The patient should be alert and cooperative. Hypoxemia (low blood levels of oxygen) or hypercapnia (high blood levels of carbon dioxide) can cause a decreased level of consciousness, irritability, anxiousness, restlessness, or confusion.

- Obtain the respiratory rate over a full minute. The normal range for the respiratory rate of an adult is 12-20 breaths per minute.

- Observe the breathing pattern, including the rhythm, effort, and use of accessory muscles. Breathing effort should be nonlabored and in a regular rhythm. Observe the depth of respiration and note if the respiration is shallow or deep. Pursed-lip breathing, nasal flaring, audible breathing, intercostal retractions, anxiety, and use of accessory muscles are signs of respiratory difficulty. Inspiration should last half as long as expiration unless the patient is active, in which case the inspiration-expiration ratio increases to 1:1.

- Observe the pattern of expiration and patient position. Patients who experience difficulty expelling air, such as those with emphysema, may have prolonged expiration cycles. Some patients may experience difficulty with breathing specifically when lying down. This symptom is known as orthopnea. Additionally, patients who are experiencing significant breathing difficulty may experience most relief while in a “tripod” position. This can be achieved by having the patient sit at the side of the bed with legs dangling toward the floor. The patient can then rest their arms on an overbed table to allow for maximum lung expansion. This position mimics the same position you might take at the end of running a race when you lean over and place your hands on your knees to “catch your breath.”

- Observe the patient’s color in their lips, face, hands, and feet. Patients with light skin tones should be pink in color. For those with darker skin tones, assess for pallor on the palms, conjunctivae, or inner aspect of the lower lip. Cyanosis is a bluish discoloration of the skin, lips, and nail beds, which may indicate decreased perfusion and oxygenation. Pallor is the loss of color, or paleness of the skin or mucous membranes and usually the result of reduced blood flow, oxygenation, or decreased number of red blood cells.

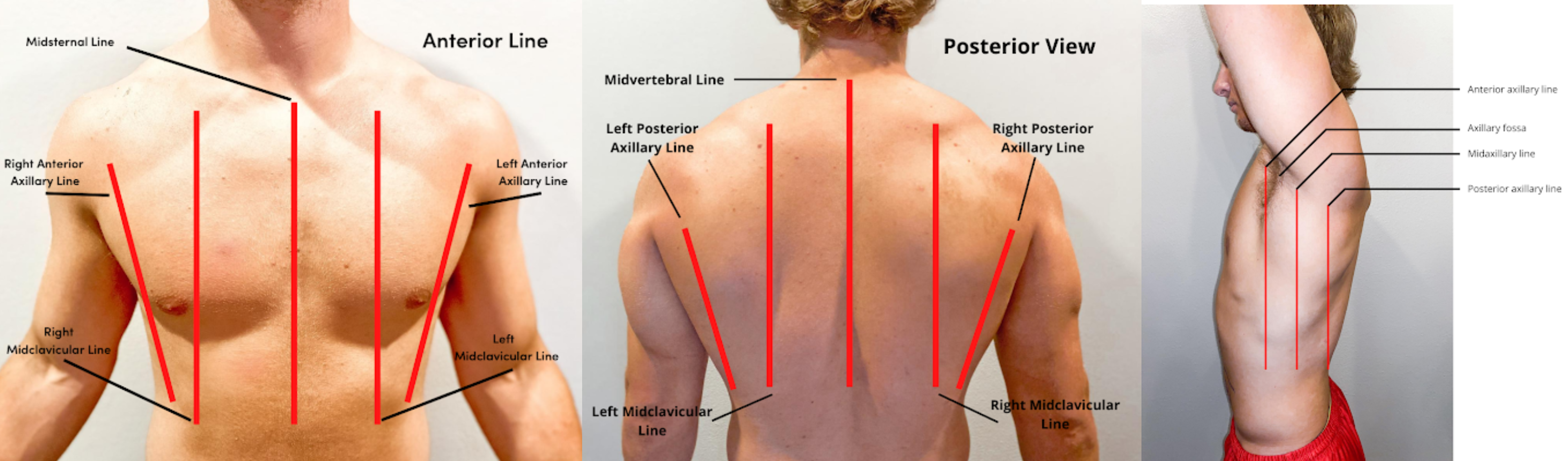

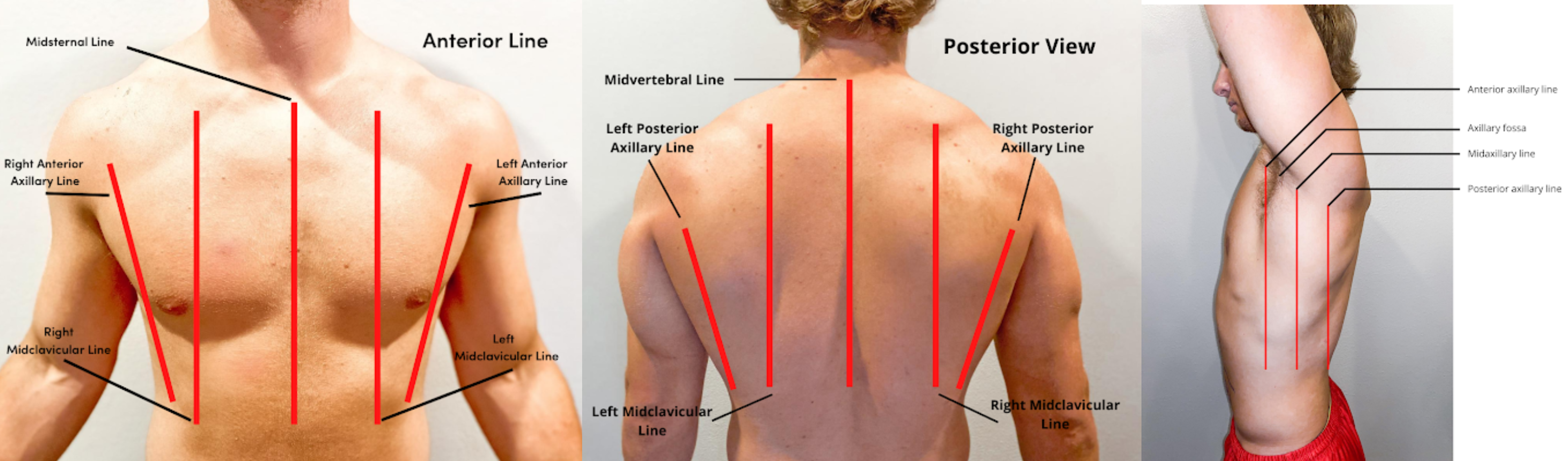

- Inspect the chest for symmetry and configuration. The trachea should be midline, and the clavicles should be symmetrical. See Figure 10.2[29] for visual landmarks when inspecting the thorax anteriorly, posteriorly, and laterally. Note the location of the ribs, sternum, clavicle, and scapula, as well as the underlying lobes of the lungs.

- Chest movement should be symmetrical on inspiration and expiration.

- Observe the anterior-posterior diameter of the patient’s chest and compare to the transverse diameter. The expected anteroposterior-transverse ratio should be 1:2. A patient with a 1:1 ratio is described as barrel-chested. This ratio is often seen in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to hyperinflation of the lungs. See Figure 10.3[30] for an image of a patient with a barrel chest.

- Older patients may have changes in their anatomy, such as kyphosis, an outward curvature of the spine.

- Inspect the fingers for clubbing if the patient has a history of chronic respiratory disease. Clubbing is a bulbous enlargement of the tips of the fingers due to chronic hypoxia. See Figure 10.4[31] for an image of clubbing.

Palpation

- Palpation of the chest may be performed to investigate for areas of abnormality related to injury or procedural complications. For example, if a patient has a chest tube or has recently had one removed, the nurse may palpate near the tube insertion site to assess for areas of air leak or crepitus. Crepitus feels like a popping or crackling sensation when the skin is palpated and is a sign of air trapped under the subcutaneous tissues. If palpating the chest, use light pressure with the fingertips to examine the anterior and posterior chest wall. Chest palpation may be performed to assess specifically for growths, masses, crepitus, pain, or tenderness.

- Confirm symmetric chest expansion by placing your hands on the anterior or posterior chest at the same level, with thumbs over the sternum anteriorly or the spine posteriorly. As the patient inhales, your thumbs should move apart symmetrically. Unequal expansion can occur with pneumonia, thoracic trauma, such as fractured ribs, or pneumothorax.

Auscultation

Using the diaphragm of the stethoscope, listen to the movement of air through the airways during inspiration and expiration. Instruct the patient to take deep breaths through their mouth. Listen through the entire respiratory cycle because different sounds may be heard on inspiration and expiration. Allow the patient to rest between respiratory cycles, if needed, to avoid fatigue with deep breathing during auscultation. As you move across the different lung fields, the sounds produced by airflow vary depending on the area you are auscultating because the size of the airways change.

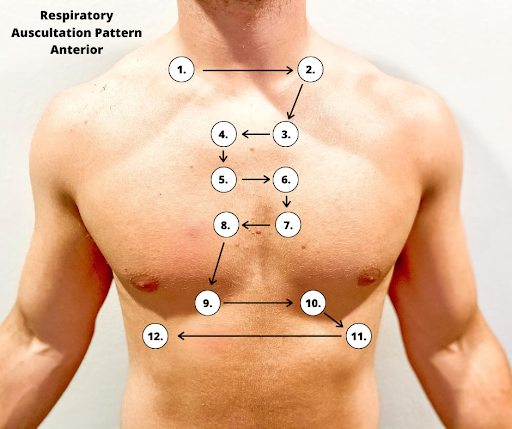

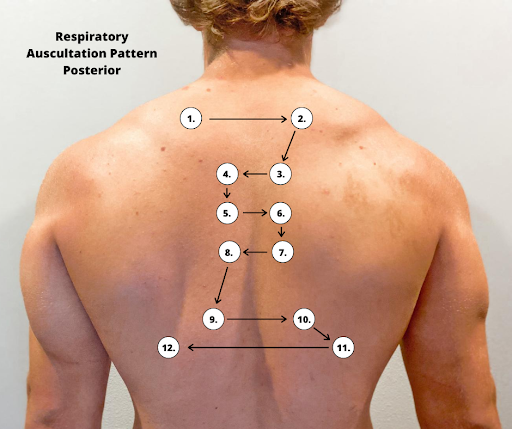

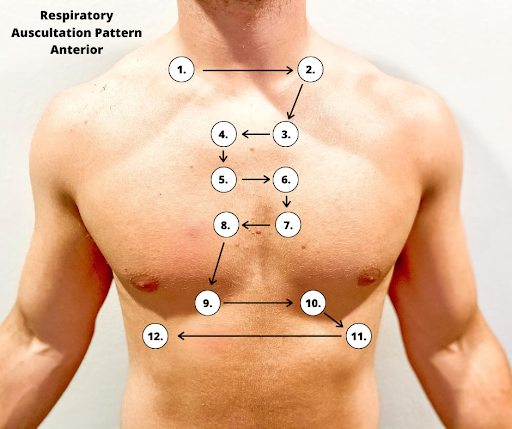

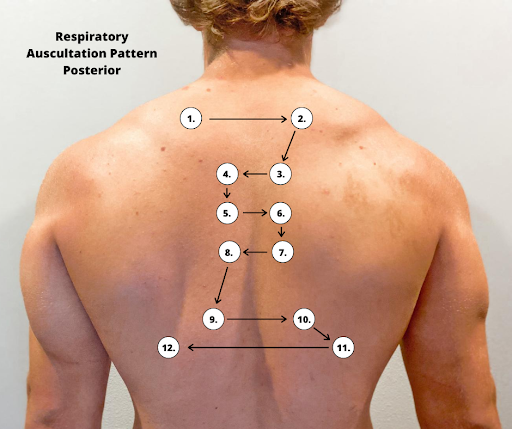

Correct placement of the stethoscope during auscultation of lung sounds is important to obtain a quality assessment. The stethoscope should not be placed over clothes or hair because these may create inaccurate sounds from friction. The best position to listen to lung sounds is with the patient sitting upright; however, if the patient is acutely ill or unable to sit upright, turn them side to side in a lying position. Avoid listening over bones, such as the scapulae or clavicles or over the female breasts to ensure you are hearing adequate sound transmission. Listen to sounds from side to side rather than down one side and then down the other side. This side-to-side pattern allows you to compare sounds in symmetrical lung fields. See Figures 10.5[32] and 10.6[33] for landmarks of stethoscope placement over the anterior and posterior chest wall.

Expected Breath Sounds

It is important upon auscultation to have awareness of expected breath sounds in various anatomical locations.

- Bronchial breath sounds are heard over the trachea and larynx and are high-pitched and loud.

- Bronchovesicular sounds are medium-pitched and heard over the major bronchi.

- Vesicular breath sounds are heard over the lung surfaces, are lower-pitched, and often described as soft, rustling sounds.

Adventitious Lung Sounds

Adventitious lung sounds are sounds heard in addition to normal breath sounds. They most often indicate an airway problem or disease, such as accumulation of mucus or fluids in the airways, obstruction, inflammation, or infection. These sounds include rales/crackles, rhonchi/wheezes, stridor, and pleural rub:

- Coarse crackles, also called rhonchi, are low-pitched, loud, continuous sounds frequently heard on expiration. They are a sign of turbulent airflow through secretions in the large airways.

Rhonchi Lung Sounds on YouTube [34]

- Fine crackles, also called rales, are popping or crackling sounds heard on inspiration. They occur in association with conditions that cause fluid to accumulate within the alveolar and interstitial spaces, such as heart failure or pneumonia. Fine crackles are soft, high-pitched, and very brief. For this reason, it is essential to listen to lung sounds with the stethoscope placed on the patient's skin and not over their clothing or hospital gown. The sound is similar to that produced by rubbing strands of hair together close to your ear.

- Wheezes are whistling-type noises produced during expiration (and sometimes inspiration) when air is forced through airways narrowed by bronchoconstriction or associated mucosal edema. For example, patients with asthma commonly have wheezing.

- Stridor is heard only on inspiration. It is associated with mechanical obstruction at the level of the trachea/upper airway.

- Pleural rub may be heard on either inspiration or expiration and sounds like the rubbing together of leather. A pleural rub is heard when there is inflammation of the lung pleura, resulting in friction as the surfaces rub against each other.[35]

Life Span Considerations

Children

There are various respiratory assessment considerations that should be noted with assessment of children.

- The respiratory rate in children less than 12 months of age can range from 30-60 breaths per minute, depending on whether the infant is asleep or active.

- Infants have irregular or periodic newborn breathing in the first few weeks of life; therefore, it is important to count the respirations for a full minute. During this time, you may notice periods of apnea lasting up to 10 seconds. This is not abnormal unless the infant is showing other signs of distress. Signs of respiratory distress in infants and children include nasal flaring and sternal or intercostal retractions.

- Up to three months of age, infants are considered “obligate” nose-breathers, meaning their breathing is primarily through the nose.

- The anteroposterior-transverse ratio is typically 1:1 until the thoracic muscles are fully developed around six years of age.

Older Adults

As the adult person ages, the cartilage and muscle support of the thorax becomes weakened and less flexible, resulting in a decrease in chest expansion. Older adults may also have weakened respiratory muscles, and breathing may become shallower. The anteroposterior-transverse ratio may be 1:1 if there is significant curvature of the spine (kyphosis).

Percussion

Percussion is an advanced respiratory assessment technique that is used by advanced practice nurses and other health care providers to gather additional data in the underlying lung tissue. By striking the fingers of one hand over the fingers of the other hand, a sound is produced over the lung fields that helps determine if fluid is present. Dull sounds are heard with high-density areas, such as pneumonia or atelectasis, whereas clear, low-pitched, hollow sounds are heard in normal lung tissue.

![]()

- Because infants breathe primarily through the nose, nasal congestion can limit the amount of air getting into the lungs.

- Attempt to assess an infant’s respiratory rate while the infant is at rest and content rather than when the infant is crying. Counting respirations by observing abdominal breathing movements may be easier for the novice nurse than counting breath sounds, as it can be difficult to differentiate lung and heart sounds when auscultating newborns.

- Auscultation of lungs during crying is not a problem. It will enhance breath sounds.

- The older patient may have a weakening of muscles that support respiration and breathing. Therefore, the patient may report tiring easily during the assessment when taking deep breaths. Break up the assessment by listening to the anterior lung sounds and then the heart sounds and allowing the patient to rest before listening to the posterior lung sounds.

- Patients with end-stage COPD may have diminished lung sounds due to decreased air movement. This abnormal assessment finding may be the patient’s baseline or normal and might also include wheezes and fine crackles as a result of chronic excess secretions and/or bronchoconstriction.[36],[37]

Expected Versus Unexpected Findings

See Table 10.3b for a comparison of expected versus unexpected findings when assessing the respiratory system.[38]

Table 10.3b Expected Versus Unexpected Respiratory Assessment Findings

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (Document and notify provider if a new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Work of breathing effortless

Regular breathing pattern Respiratory rate within normal range for age Chest expansion symmetrical Absence of cyanosis or pallor Absence of accessory muscle use, retractions, and/or nasal flaring Anteroposterior: transverse diameter ratio 1:2 |

Labored breathing

Irregular rhythm Increased or decreased respiratory rate Accessory muscle use, pursed-lip breathing, nasal flaring (infants), and/or retractions Presence of cyanosis or pallor Asymmetrical chest expansion Clubbing of fingernails |

| Palpation | No pain or tenderness with palpation. Skin warm and dry; no crepitus or masses | Pain or tenderness with palpation, crepitus, palpable masses, or lumps |

| Percussion | Clear, low-pitched, hollow sound in normal lung tissue | Dull sounds heard with high-density areas, such as pneumonia or atelectasis |

| Auscultation | Bronchovesicular and vesicular sounds heard over appropriate areas

Absence of adventitious lung sounds |

Diminished lung sounds

Adventitious lung sounds, such as fine crackles/rales, wheezing, stridor, or pleural rub |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS to report immediately | Decreased oxygen saturation <92%[39]

Pain Worsening dyspnea Decreased level of consciousness, restlessness, anxiousness, and/or irritability |

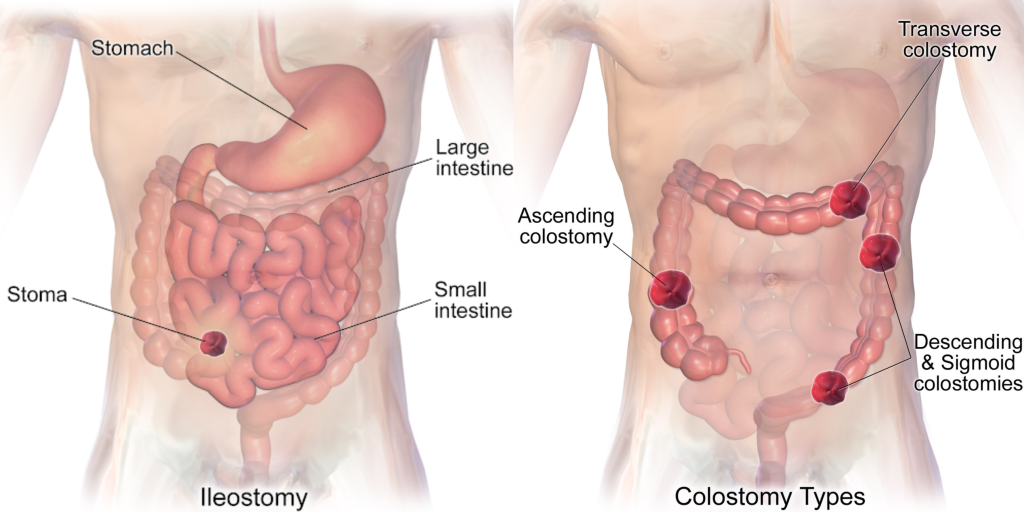

An ostomy is the surgical procedure that creates an opening (stoma) from an area inside the body to the outside of the body. In ostomies related to elimination, a stoma is an opening on the abdomen that is connected to the gastrointestinal or urinary system to allow waste (i.e., urine or feces) to be collected in a pouch. See Figure 21.14[40] for an image of a stoma. A stoma can be permanent, such as when an organ is removed, or temporary, such as when an organ requires time to heal. Ostomies are created for patients with conditions such as cancer of the bowel or bladder, inflammatory bowel diseases, or perforation of the colon.

There are several different kinds of ostomies related to elimination. Common types of ostomies include the following:

- Ileostomy: The lower end of the small intestine (ileum) is attached to a stoma to bypass the colon, rectum, and anus.

- Colostomy: The colon is attached to a stoma to bypass the rectum and the anus.

- Urostomy: The ureters (tubes that carry urine from the kidney to the bladder) are attached to a stoma to bypass the bladder.[41]

See Figure 21.15[42] comparing the anatomical locations of ileostomies and various sites of colostomies. It is important for the nurse to understand the site of a patient’s colostomy because the site impacts the characteristics of the waste. For example, due to the natural digestive process of the colon and absorption of water, waste from an ileostomy or a colostomy placed in the anterior ascending colon will be watery compared to waste from an ostomy placed in the descending colon.

The tissue of a stoma is very delicate. Immediately after surgery, a stoma is swollen, but it will shrink in size over several weeks. A healthy, healed stoma appears moist and dark red or pink in color. Stomas that are swollen; dry; have malodorous discharge; or are bluish, purple, black, or pale should be reported to the provider. The skin surrounding a stoma can easily become irritated from the pouch adhesive or leakage of fluid from the stoma, so the nurse must perform interventions to prevent skin breakdown. Any identified signs of skin breakdown should be reported to the provider.[43]

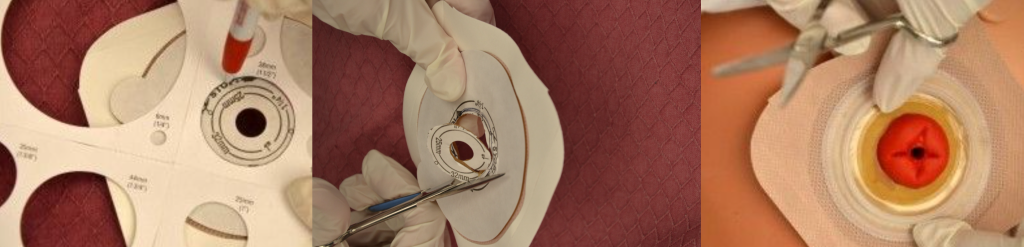

Stoma appliances are supplied as a one- or two-piece set. A two-piece set consists of an ostomy barrier (also called a wafer) and a pouch. The ostomy barrier is the part of the appliance that sticks to the skin with a hole that is fitted around the stoma. The pouch collects the waste and must be emptied regularly. It attaches to the ostomy barrier in a clicking motion to secure the two parts, similar to how a plastic storage container cover snaps to a container to create a seal. The pouching system must be completely sealed to prevent leaking of the waste and to protect the surrounding peristomal skin. The pouch has an end with an opening where the waste is drained and is closed using a plastic clip or VelcroTM strip.[44] In a one-piece stoma appliance set, the ostomy barrier and the pouch are one piece. See Figure 21.16[45] for an image of a stoma with an ostomy barrier in place. See Figure 21.17[46] for an image of a patient with an ileostomy appliance with a pouch attached.

Individuals with colostomies, ileostomies, and urostomies have no sensation and no control over the output of the stoma. Depending on the type of system, the ostomy appliance can last from four to seven days, but the pouch must be changed if there is leaking, odor, excessive skin exposure, or itching or burning under the skin barrier. Patients with pouches can swim and take showers with the pouching system on.[47]

When changing an ostomy appliance, the ostomy barrier is cut to fit closely around the stoma without impinging on it. See the "Checklist for Ostomy Appliance Change" for detailed instructions. The nurse measures the stoma with a template and then cuts and fits the ostomy barrier to a size that is 2 mm larger than the stoma.[48] See Figure 21.18[49] for an image of a nurse measuring and cutting the ostomy barrier to fit around a stoma.

After the skin barrier is applied to the skin, the pouch is snapped to the barrier. See Figure 21.19[50] for an image of applying the pouch.

Physical and Emotional Assessment

Patients may have other medical conditions that affect their ability to manage their ostomy care. Conditions such as arthritis, vision changes, Parkinson’s disease, or post-stroke complications can hinder a patient’s coordination and ability to manage the ostomy. In addition, the emotional burden of coping with an ostomy may be devastating for some patients and may affect their self-esteem, body image, quality of life, and ability to be intimate. It is common for patients with ostomies to struggle with body image and their altered pattern of elimination. Nurses can promote healthy coping by ensuring the patient has appropriate referrals to a wound/ostomy nurse specialist, a social worker, and support groups. Nurses should also be aware of their nonverbal cues when assisting a patient with their appliance changes. It is vital not to show signs of disgust at the appearance of the ostomy or at the odor that may be present when changing an appliance or pouching system.[51]

View a supplementary YouTube video on Changing an Ostomy Pouch[52]

Urostomy Care

A urostomy is similar to a colostomy, but it is an artificial opening for passing urine. Urostomies are surgically created due to medical conditions such as bladder cancer, removal of the bladder, trauma, spinal cord injuries, or congenital abnormalities.

A urostomy patient has no voluntary control of urine, so the pouching system must be emptied regularly. Many patients empty their urostomy bag every two to four hours or when the pouch becomes one-third full. The pouch may also be attached to a drainage bag for overnight drainage. Patients with a urostomy are at risk for urinary tract infections (UTIs), so it is important to educate them regarding the signs and symptoms of an infection.

If a small amount of a fresh urine is needed for specimen collection for urinalysis or culture, aspirate the urine from the needleless sampling port with a sterile syringe after cleansing the port with a disinfectant.[53] See the "Checklist for Obtaining a Urine Specimen from a Foley Catheter" for more detailed instructions. Do not collect the urine that is already in the collection bag because it is contaminated and will lead to an erroneous test result.

It is the nurse’s responsibility to assess for a patient’s continued need for an indwelling catheter daily and to advocate for removal when appropriate.[54] Prolonged use of indwelling catheters increases the risk of developing CAUTIs. For patients who require an indwelling catheter for operative purposes, the catheter is typically removed within 24 hours or less. Some agencies have a protocol for the removal of indwelling catheters, whereas others require a prescription from a provider. For additional instructions about how to remove an indwelling catheter, see the "Checklist for Foley Removal."

When removing an indwelling urinary catheter, it is considered a standard of practice to document the time and track the time of the first void. This information is also communicated during handoff reports. If the patient is unable to void within 4-6 hours and/or complains of bladder fullness, the nurse determines if incomplete bladder emptying is occurring according to agency policy. The ANA has made the following recommendations to assess for incomplete bladder emptying:

- The patient should be prompted to urinate.

- If urination volume is less than 180 mL, the nurse should perform a bladder scan to determine the post-void residual. A bladder scan is a bedside test performed by nurses that uses ultrasonic waves to determine the amount of fluid in the bladder.

- If a bladder scanner is not available, a straight urinary catheterization is performed.[55]

When a urinary catheter is removed, instruct the patient on the following guidelines:

- Increase or maintain fluid intake (unless contraindicated).

- Void when able with the goal to urinate within six hours after removal of the catheter. Inform the nurse of the void so that the amount can be measured and documented.

- Be aware that there may be a mild burning sensation during the first void.

- Report any burning, discomfort, frequency, or small amounts of urine when voiding.

- Report an inability to void, bladder tenderness, or distension.

When preparing to insert an indwelling urinary catheter, it is important to use the nursing process to plan and provide care to the patient. Begin by assessing the appropriateness of inserting an indwelling catheter according to CDC criteria as discussed in the “Preventing CAUTI” section of this chapter. Determine if alternative measures can be used to facilitate elimination and address any concerns with the prescribing provider before proceeding with the provider order.

Subjective Assessment

In addition to verifying the appropriateness of the insertion of an indwelling catheter according to CDC recommendations, it is also important to assess for any conditions that may interfere with the insertion of a urinary catheter when feasible. See suggested interview questions prior to inserting an indwelling catheter and their rationale in Table 21.8a.

Table 21.8a Suggested Interview Questions Prior to Urinary Catheterization

| Interview Questions | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Do you have any history of urinary problems such as frequent urinary tract infections, urinary tract surgeries, or bladder cancer?

For males: Do you have any history of prostate enlargement or prostate problems? For females: Have you had any gynecological surgeries? |

Previous medical conditions and surgeries may interfere with urinary catheter placement. Information about a male patient’s prostate will assist in determining the size and type of catheter used. (Recall that using a catheter with a coude tip is helpful when a male patient has an enlarged prostate.) If a patient has a history of previous urinary tract infections, they may be at higher risk of developing CAUTI. |

| Have you ever had a urinary catheter placed in the past? If so, were there any problems with placement or did you experience any problems while the catheter was in place? | Questioning the patient about placement and prior catheterizations assists the nurse in identifying any problems with catheterization or if the patient has had the procedure before, they may know what to expect. |

| Do you have any questions about this procedure? How do you feel about undergoing catheterization? | The nurse should encourage patient involvement with their care and identify any fears or anxiety. Nurses can decrease or eliminate these fears and anxieties with additional information or reassurance. |

| Do you take any medications that increase urination such as diuretics or any medications that decrease urgency or frequency? If so, please describe. | Identifying medications that increase or decrease urine output is important to consider when monitoring urine output after the catheter is in place. |

| Have you had any orthopedic surgeries that may affect your ability to bend your knees or hips? Are you able to tolerate lying flat for a short period of time? | The patient may not be able to tolerate the positioning required for catheter insertion. If so, additional assistance from other staff may be required for patient comfort and safety. |

Cultural Considerations

When inserting urinary catheters, be aware of and respect cultural beliefs related to privacy, family involvement, and the request for a same-gender nurse. Inserting a urinary catheter requires visualization and manipulation of anatomical areas that are considered private by most patients. These procedures can cause emotional distress, especially if the patient has experienced any history of abuse or trauma.

Objective Assessment

In addition to performing a subjective assessment, there are several objective assessments to complete prior to insertion. See Table 21.8b for a list of objective assessments and their rationale.

Table 21.8b Objective Assessment

| Objective Data Collection | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Review the patient’s medical record for any documented medical conditions the patient may not have reported, such as urethral strictures, structural problems with the bladder or urethra, or frequent urinary tract infections. | Any type of obstruction or scar tissue within these areas may prevent the catheter from advancing into the bladder. |

| Analyze the patient's weight and most recent electrolyte values. | Weight is used to determine a patient's fluid status, especially if they have fluid overload. Electrolyte levels are also affected by fluid balance and the use of diuretic medications. Establish a baseline to use to evaluate outcomes after placing the urinary catheter. |

| Determine the patient's level of consciousness, ability to cooperate, developmental level, and age. | Evaluate the patient’s ability to follow directions and cooperate during the procedure and seek additional assistance during the procedure if needed. This data will impact how to explain the procedure to the patient. |

| Perform physical assessment of the bladder and perineum. Palpate the bladder for signs of fullness and discomfort. (Bladder emptying may also be assessed using a bladder scanner per agency policy). Inspect the perineum for erythema, discharge, drainage, skin ulcerations, or odor. Note the position of anatomical landmarks. For example, in females identify the urethra versus the vaginal opening. | A full bladder produces discomfort and urgency to void, especially on palpation. These symptoms should be relieved with the placement of a urinary catheter.

Identify any abnormal physical signs in the perineal area that may interfere with comfort during insertion. Determining the urethral opening improves accuracy and ease of insertion. |

| When examining the perineal area, note the approximate diameter of the urinary meatus. Choose the smallest, appropriately sized diameter catheter. | An appropriately sized catheter is important to avoid unnecessary discomfort or trauma to the urinary tissue. Catheters that are 14 French diameter are typically used in adults. |

Life Span Considerations

Children

It is often helpful to explain the catheterization procedure using a doll or toy. According to agency policy, a parent, caregiver, or other adult should be present in the room during the procedure. Asking a younger child to blow into a straw can help relax the pelvic muscles during catheterization.

Older Adults

The urethral meatus of older women may be difficult to identify due to atrophy of the urogenital tissue. The risk of developing a urinary tract infection may also be increased due to chronic disease and incontinence.

Expected Outcomes/Planning

Expected patient outcomes following urinary catheterization should be planned and then evaluated and documented after the procedure is completed. See Table 21.8c for sample expected outcomes related to urinary catheterization.

Table 21.8c Expected Outcomes of Urinary Catheterization

| Expected Outcomes | Rationale |

|---|---|

| The patient’s bladder is nondistended and not palpable. | Verifies appropriate bladder emptying. |

| The patient reports no abdominal or bladder discomfort or pressure. | Verifies correct catheter placement by allowing urine flow and relieving discomfort or pressure. |

| Urine output is at least 30 mL/hr. | Verifies correct catheter placement and appropriate kidney functioning. If urine output is less than 30 mL/hour, check tubing for kinking and obstruction, and notify the provider if there is no improvement after manipulating the tubing. |

| Patient verbalizes understanding of the purpose of the catheter and signs of a urinary tract infection to report. | Verifies the patient's understanding of the procedure and signs of complications. |

Implementation

When inserting an indwelling urinary catheter, the expected finding is that the catheter is inserted accurately and without discomfort, and immediate flow of clear, yellow urine into the collection bag occurs. However, unexpected events and findings can occur. See Table 21.8d for examples of unexpected findings and suggested follow-up actions.

Table 21.8d Unexpected Findings and Follow-Up Actions

| Unexpected Findings | Follow-Up Action |

|---|---|

| Urine flow does not occur when catheterizing a female patient. | The catheter may have entered the vagina and not the urethral meatus. Leave the catheter in the vagina as a landmark to avoid incorrect reinsertion. Obtain a new catheter kit and cleanse the urinary meatus again before reinsertion. If reinsertion is successful into the bladder, remove the catheter that is in vagina after the second attempt. |

| Sterile field is broken during the procedure. | If supplies or the catheter become contaminated, obtain a new catheter kit and restart the procedure. |

| Patient reports continued bladder pain or discomfort although urinary flow indicates correct catheter placement. | Ensure there is no tension pulling at the catheter. It may be helpful to deflate the balloon and advance the catheter another 2-3 inches to ensure it is in the bladder and not the urethra. If these actions do not resolve the discomfort, notify the provider because it is possible the patient is experiencing bladder spasms. Continue to monitor urine output for clarity, color, and amount and for signs of urinary tract infection. |

| The nurse is unable to advance the catheter on a male patient with an enlarged prostate. | Do not force advancement because this may cause further damage. Ask the patient to take deep breaths and try again. If a second attempt is unsuccessful, obtain a coude catheter and attempt to reinsert. If unsuccessful with a coude catheter, notify the provider. |

| Urine is cloudy, concentrated, malodorous, dark amber in color, or contains sediment, blood, or pus. | Notify the health care provider of signs and symptoms of a possible urinary tract infection. Obtain a urine specimen as prescribed. |

Evaluation

Evaluate the success of the expected outcomes established prior to the procedure.

Sample Documentation for Expected Findings