Interpreting for a Pediatric Client – Medical Setting

Bridget Morina-Meyer

A pediatric client is a Deaf child in a medical environment. In this setting, an interpreter may work with an inpatient at a hospital; an in-person doctor’s appointment or one held via video remote interpreting (VRI); or an appointment between a Deaf child and a mental health professional. A pediatric patient can be anywhere between the ages of 0 to 21 years. Children, especially younger ones, will have limited experience with interpreters at their medical appointments. Interpreters will face challenges and unique factors that affect communication during these assignments. The following chapter discusses specifics for interpreting which allows children access to important health care information thus impacting the rest of their lives.

Language Deprivation and Access to Medical Knowledge

A certified interpreter is required for all pediatric assignments, and a Deaf/hearing team of interpreters is necessary for mental health and perhaps other appointments. With diligent consideration, a qualified interpreter who is not yet certified and has experience with children may also be appropriate. It is important to note that not all deaf children are fluent in sign language. Often hearing parents, learning that their child is deaf, pursue only oral methods of communication. For example, focusing on spoken language being dependent on auditory input via hearing aids or cochlear implants. In these situations, the child will have limited exposure, if any, to sign language until they go to school. This is one of the reasons why language deprivation is common among Deaf children:

Often, deaf children do not have full access to language during the critical period. This is known as ‘language deprivation.’ This lack of access to language causes significant delays in language development. Language deprivation does not only impact language, it also has a significant impact on other areas of human development. In the US, researchers refer to this as ‘language deprivation syndrome,’ where deaf children have an acquired language disorder due to a lack of access to language in the first few years of life. (Rowley & Sive, 2021, p. 32)

Medical appointments can be deceivingly complicated. Interpreters working with children in a pediatric setting will encounter ethical dilemmas including, but not limited to the following scenarios:

- Medical providers being unaware of the importance of an American Sign Language (ASL)/English interpreter during an appointment.

- Providers only focused on the medical, not the communication, needs of a child.

- Adults having the belief that a child does not have enough knowledge of sign language to understand an interpreter.

- Likewise, people assume that if the child does not look at the interpreter there is no need to provide interpretation.

- Parents hold the assumption that they are protecting children by not providing access to medical information, and it is better that they do not know so they will not be scared.

Recognizing disparities both among language modalities and among the skill levels of language models for deaf children, the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) states:

The effects of early language deprivation or limited exposure to language due to not having sufficient access to spoken language or sign language are often so severe as to result in serious health, education and quality of life issues for these children (NAD, 2014, para. 1).

To further support the use of sign language interpreters in a medical setting for a child, Hauser stated “if deaf infants and toddlers are not provided their right to access to language early in life, then the language deprivation will affect their education… This includes health education, which directly affects their health knowledge and literacy” (World Federation of the Deaf, 2018, para. 6). During a presentation, Montoya, a Child and Family Therapist shared, “Just being Deaf significantly increases chances of experiencing a preventable adverse medical event” (Montoya, Morina-Meyer & McHenry, 2019).

In addition to guidance from the NAD and professionals who work with Deaf children, research supports the need for access to quality language as well. To understand the impacts of such disparities we need only to look at Deaf adults’ medical outcomes.

- Deaf people who use sign language see doctors less often (Barnett & Franks, 2002).

- Deaf individuals struggle with lower ‘fund of health knowledge’ (R. Pollard, 1998 as cited in McKee et al., 2015, p. 6).

- Deaf people disclosed that they had less sexual information than hearing people, (Heuttel & Rothstein, 2001) have less knowledge of cardiovascular disease than hearing counterparts. (Margellos-Anast et al., 2006) and are at higher risk of contracting HIV (Peinkofer, 1994).

- “Deaf and hard-of-hearing persons were less likely to report receiving preventive information from physicians or the media…” (Tamaskar et al., 2000, para. 2).

- “Studies show that deaf patients, compared to hearing patients, make less frequent visits to their primary care provider, and make more trips to the emergency room” (Hoglind, 2018, para. 2).

- Deaf individuals often are unaware of family members’ medical diagnosis, nor understand its importance in their own health care (Barnett, 1999).

- 60% percent of deaf adults in a U.S. study could not list any symptoms of stroke, compared to 30% of hearing adults (Margellos-Anast et al., 2006).

- Only 49% of deaf adults in a U.S. study could identify chest pain/pressure as a heart attack symptom, compared to 90% of hearing adults (Margellos-Anas, et al., 2006).

Childhood is where health literacy begins, and this disparity in healthcare knowledge begins from a Deaf person’s first experience with medical providers. If no interpreter is provided and no one is trying to engage the child, with accessible and age-appropriate language, how can a Deaf child begin a health literacy journey?

As a society, Americans do not purposely educate our children to be consumers of healthcare. We do not intentionally instruct the next generation on how to attend medical appointments nor how to interact with medical providers. We learn how to use such services by watching our parents, guardians, or caregivers interact with medical providers on our behalf, until we can assume that responsibility for ourselves. Children cannot learn from their parents at medical appointments if they do not have access to language and the consequences can be detrimental for the rest of their lives.

The Challenge of Interpreting for Deaf Children

To complicate the situation even more, Interpreter Programs almost exclusively teach about working with Deaf adults. There is little education content available for working with Deaf children and child-centered content tends to be academically focused where the interpreter works in a school setting.

Interpreting for children is different than interpreting for adults. A Deaf adult leads the interaction with the provider. Most likely, they have experience with interpreters and a vested interest in what is being said and in getting correct information. It is highly likely that a pediatric client does not care if an interpreter is present, may not take part in the appointment, and may not be interested in the information being shared. They may or may not even make eye-contact or engage with the interpreter at all. Regardless, the interpreter’s presence is imperative.

Deaf children learn to use an interpreter through experience. The importance of involving interpreters when Deaf children are young cannot be underestimated. It is an opportunity to improve comfort levels as well as allowing children to access healthcare literacy in these environments. On meeting the family in the waiting room, the interpreter should take the opportunity to help put the child and parent at ease. Simply smiling, being friendly and engaging the child will be beneficial for when it is time to go back to the treatment room. For younger children, be willing to “play.” A child may be very shy, and uncomfortable with new people. In such situations, take a step back but remain approachable; it is important the child become accustomed to interpreters at their appointments.

Prior access to information about the child and the appointment is extremely helpful, however it can be challenging to obtain. Although interpreters are included in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), professionals may be resistant to sharing information, especially if they rarely collaborate with interpreters. The information may be available from the agency, interpreters who have previously interpreted for the patient, a staff interpreter (if there is one), the healthcare provider (you can remind them you are part of the care team), parents, and even the child.

It is helpful when working with children to use a Deaf Centered Approach to appropriately accommodate the interpretation. This means you are meeting the Deaf person at their language and communication level. When doing this, consider the following Six Areas between the interpreter and the pediatric consumer:

- Language of the child

- Education of the child

- Other medical diagnoses of the child

- Parents or Guardians at the appointment

- Provider of medical services

- You! The interpreter

Area 1: Language of the Child

It is important to know how the child communicates. It may include ASL, Contact Sign, another signed language, other gestural forms of communication, Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART), or a communication device. It may be a combination of two or more of these things as well. While in the waiting room, you can take note of any assistive devices; do they have a cochlear implant, or wear a hearing aid? The parent or healthcare provider may be able to provide you with information. You can also ask the consumer directly and/or engage with them in the waiting room to gather information.

Watch how the child interacts with the parent. Do they use sign language or spoken language to communicate? Does the child use CART or have an assistive device? Are those in addition to using sign language or are they “trying out” using an interpreter? You will need to continually assess the communication and adjust your sign choices. Even with limited language, there are several strategies and techniques to include Deaf children in their appointments. These include hiring an interpreter for all medical encounters, or an interpreting team (Deaf and hearing interpreters), using visual-gestural communication, drawing pictures, and/or using pictures from the internet.

Area 2: Education of the Child

As well as using the strategies already mentioned, you can ask questions about the child’s school setting. A parent or child may not be able to tell you if they are more “ASL or Contact Sign,” but asking about the child’s education can provide insight into the language modality used at school. For example, schools for the Deaf that use ASL tend to give students access to visual language all day with classmates, teachers, and staff that sign. In situations where a child is in a mainstream classroom, surrounded by hearing children and adults, you may need to tailor your interpretation more toward Contact Sign. Deaf students attending mainstream schools can also be in a self-contained classroom taught by a special education teacher along with Deaf peers or with classmates who have other special needs. The Deaf child may spend all day in that room, or parts of day mainstreamed into a hearing classroom. Again, in these situations, you may want to lean your interpretation toward more Contact Sign.

On occasion you may meet a Deaf child who has had no formal education. These situations are the most challenging, especially if they have other diagnoses. A Certified Deaf Interpreter (CDI) will need to join the hearing interpreter for all appointments. See Wanis and; Bentley-Sassaman and Schmerman (this volume) information on CDIs. If you are meeting the child for the first time and you are working without a CDI, ensure you strongly suggest to the healthcare provider they request a Deaf/hearing interpreting team for future appointments.

Area 3: Other Medical Diagnoses of the Child

If a child has additional medical diagnoses, it may affect your interpreting. For example, if the child has a significant vision loss or is blind, any interpreter may need to employ tactile signing or use a reduced signing space to accommodate the child’s vision field. If a child is missing an arm or fingers, they may be difficult to understand when signing. It is okay to team up with the parent or healthcare provider for more effective communication and certainly let them know if the message is unclear. Keep in mind, some diagnoses may not be obvious. For example, a child who has an attention deficit issue may not be able to “attend” to the message. Again, share these observations and concerns with those in the room being cognizant that you are the language authority.

Area 4: Parents or Guardians at the Appointment

Up to 95% of all Deaf children are born to hearing parents. Most of these parents have no knowledge of sign language or deafness prior to their baby’s diagnosis. Regardless of recommendations to learn sign language, some parents are either incapable of, or resistant to, learning a language that would enable them to better communicate with their Deaf child (Caselli et al., 2021). It is very possible when meeting a family, you as the interpreter are better able to communicate with the Deaf child than the child’s own parents. A parent may ask the interpreter to “tell” the child something that they have not had success at communicating themselves – sometimes things as simple as “tell them to brush their teeth.”

As difficult as it may be, remember to keep criticism and harsh judgment about the parents or family out of the interaction. Families with Deaf children have complicated lives. They also do not have the education that an interpreter has about deafness. At the beginning of the appointment, remind all parties that everything said will be interpreted, and as always, remain professional regardless of your opinion. Be prepared to hear and interpret difficult, firsthand experiences. And, keep in mind that your presence in the room is important and impactful as it may determine if an interpreter will be used in future appointments.

Sometimes, parents do not want an interpreter at the appointment as they may feel threatened by the interpreter’s ability to communicate with their child. Or they may have something to hide. Or they may think they are protecting their child from “scary” information. This is simply not true. If you can remember your own doctors’ appointments when you were a child, the scariest part is NOT knowing what is going to happen.

Your child will feel more secure knowing what’s going to happen and why. Kids can cope with discomfort or pain more easily if they know about it ahead of time, and they’ll learn to trust you if you’re honest with them (Gupta, 2023, para. 21-22).

If a parent requests you leave before or during the appointment, consult privately with the healthcare provider to advocate for the child and language access. You may suggest they inform the parent that it is “hospital/office protocol” to provide interpreters not just for the benefit of the child, but for the doctor to be able to communicate directly with the patient.

Area 5: Provider of Medical Services

Healthcare providers tend to be unaware of the importance of an ASL-English interpreter during an appointment. Often, they believe the parents will explain to the child what happened during the interaction. Due to the healthcare providers’ limited understanding of deafness and language deprivation, they do not fully appreciate the lack of communication that can occur in hearing families with Deaf children. By relying solely on the parents for information, the Deaf child may not have access to what occurred during the appointment. Another concern with busy healthcare professionals is the guardian makes the decisions related to the child’s health; therefore, the child’s input or understanding is frequently undervalued. In the unique situations when the healthcare provider has prior knowledge and an understanding of the child, they may be able to give the interpreter information about the patient’s communication practices.

It is best practice for the interpreter to pre- and post-conference with the healthcare professional when possible. Admittedly, it can be challenging to have a meeting with the healthcare provider before an appointment; however, the interpreter can ask the purpose, or goals, of the appointment while walking back to the examination room, or while waiting for the healthcare provider outside the room. An interpreter can also discretely ask for a moment to speak to the healthcare provider after the appointment. If you suspect the child did not understand the interpretation or has limited language ability, use these opportunities to suggest the provider request a CDI for future appointments.

Area 6: You! The Interpreter

There is you in the appointment! Of course, we all have our own “stuff” that we bring into any assignment but the best thing we can do for the Deaf child, and everyone involved, is to put those things aside and be fully present as the interpreter. This means prioritizing and focusing on the interaction in that moment. Mistakes will happen, and that is okay. Ensure you consider how to improve for the next time and do not be afraid to let go of interpreting constraints that are used with Deaf adults: play, draw, use online images and graphics—whatever produces the best access. Do not underestimate your knowledge and your importance in what may be a brief encounter. Interpreters can influence Deaf children’s health literacy for the rest of their lives.

Developmental Age and Interpreting

Interpreting is not based on the chronological age of the child but rather on the developmental age. A child may chronologically be twelve years old, but developmentally, three years old. It is helpful to have a brief understanding of child development by stages and ages.

Under Three Years Old

Very rarely (but it can happen) an interpreter is present at a medical appointment for a child under the age of three. At this age, a Deaf child is unaware of a Deaf or hearing identity. However, if children are fortunate enough to have people in their lives who request an interpreter for their medical appointments, they will likely learn from this important life-long advocacy opportunity. Interpret, but keep the message brief, one or two labeling words, “mommy,” “doctor,” “bed,” “sleep,” and so forth.

Three to Six Years Old

At three to six years of age, a child may begin to understand the role of the interpreter (Montoya et al., 2019). Children may also have misconceptions about deafness, for example, thinking they will become hearing when they grow up. Or they may believe they will never grow, because all the adults they know are hearing. These are the “magical thinking” years (Montoya et al., 2019). The child may not have age-appropriate social skills and underscores the importance of developing a rapport by playing with the child and increase their comfort level. The interpreter must focus on building trust with the child while also listening to the conversation to provide quick “interpretations” of the appointment, e.g., “they’re talking about you, about school about the teacher…”

Six to Eleven Years Old

When Deaf children are between the ages of six to eleven, they are either excited to be involved and take part – not recognizing a difference between themselves and their hearing friends. Or, they become bored and take a step back, disengaging from their peers (Montoya et al., 2019). This is a slippery slope as it can begin the experience of learned helplessness.

Learned helplessness occurs when an individual continuously faces a negative, uncontrollable situation and stops trying to change their circumstances, even when they have the ability to do so. For example, a smoker may repeatedly try and fail to quit. He may grow frustrated and come to believe that nothing he does will help, and therefore he stops trying altogether. The perception that one cannot control the situation essentially elicits a passive response to the harm that is occurring (Psychology Today, 2023, para.1).

Eleven to Fifteen Years Old

At the beginning of the teenage years, ages 11 to 12, children want to look and seem just like their friends. Around the ages of 13 to 15 years, they begin to become fully aware of their differences and a Deaf child may have feelings like “I am different,” “I am unique,” “I am a freak.” These differences may become more noticeable to the teenager, especially if they have younger siblings who are coming home with harder homework and more complex reading and writing assignments.

For typically developing Deaf teens with age appropriate ASL skills, they often begin to minimize the need for an interpreter. They may feel embarrassed about having an interpreter and they may come to understand for the first time that English and ASL are different languages. A Deaf teenager may be questioning their Deaf identity, they may begin to grieve their differences. And often Deaf teens do not have people they can clearly communicate with to discuss these culturally sensitive feelings (Montoya, et al., 2019).

At this age Deaf teens are aware of the role of an interpreter and often take interest in the information being shared during a meeting. Or the Deaf child may not want to look at the interpreter. Regardless, we continue to interpret. In situations like this, not looking at the Deaf patient directly is less threatening and may allow them to take in more information. An interpreter can ask for understanding checks using the phrase “Was I clear?” This puts the responsibility on the interpreter as opposed to the Deaf child. Phrasing like, “Do you understand?” may make the child feel inadequate and is often an ineffective gauge. And ensure you interpret while the Deaf patient is at the checkout desk after the appointment to encourage self-advocacy skills by asking if the child would like to request the scheduler provide an interpreter at the next appointment.

Fifteen Years Old and Above

As the Deaf child becomes an older teenager, they will have more language and a better understanding of the role of the interpreter. To blend in, an adolescent may try to act “hearing” and minimize the need for an interpreter. “I don’t really need you, I can hear with my hearing aid, cochlear implant, etc.” Unless the child is exclusively oral, they will still need the interpreter.

Another problematic situation can arise if the Deaf adolescent expresses a preference for the interpreter rather than the parent. The teen may leave the parent out of the conversation, only signing with the interpreter. Furthermore, strife between Deaf teens and their parents can arise, especially if the communication is easier with an interpreter. Interpreters should avoid getting involved in these conflicts. By this time, the teen may have already perfected, intentionally, or unintentionally, a learned helplessness strategy (Psychology Today, 2023).

Collaborating with a Certified Deaf Interpreter (CDI)

A CDI is a fantastic addition to the communication team for Deaf children. Observing CDIs working with Deaf children will yield many strategies. A CDI often has a better understanding of what the Deaf child is experiencing because they too were once a Deaf child. The interpreter’s goal should always be to promote clear and effective communication.

Families from other countries may require an additional spoken language interpreter to be involved in the visit. There could be up to three interpreters for an appointment: a spoken language interpreter, and a Deaf/hearing team of interpreters. This unique situation requires tremendous teamwork among the interpreters. Often while a message is being conveyed between the CDI and the Deaf child, hearing people will use the “silence” as an opportunity to continue to speak. When they do this, the Deaf child is left out of conversation about their own health care. As the CDI is busy with the interpretation, it is the responsibility of the hearing interpreter to manage the flow of the conversation. This may be uncomfortable for the hearing interpreter, as they typically defer to the CDI, however, the hearing interpreter is the person in the room who understands all the moving parts and has access to all the communication taking place. The hearing interpreter may look like a traffic officer, holding a hand up while waiting for the Deaf child to have his or her say. As always, the hearing interpreter should defer to the CDI about language choices. These types of situations are truly a team effort. At the beginning of the appointment, the interpreter team needs to explain that there can only be one person talking at a time and more than likely, the hearing interpreter will need to reiterate that statement during the session.

Ethical Considerations in Pediatric Medical Interpreting

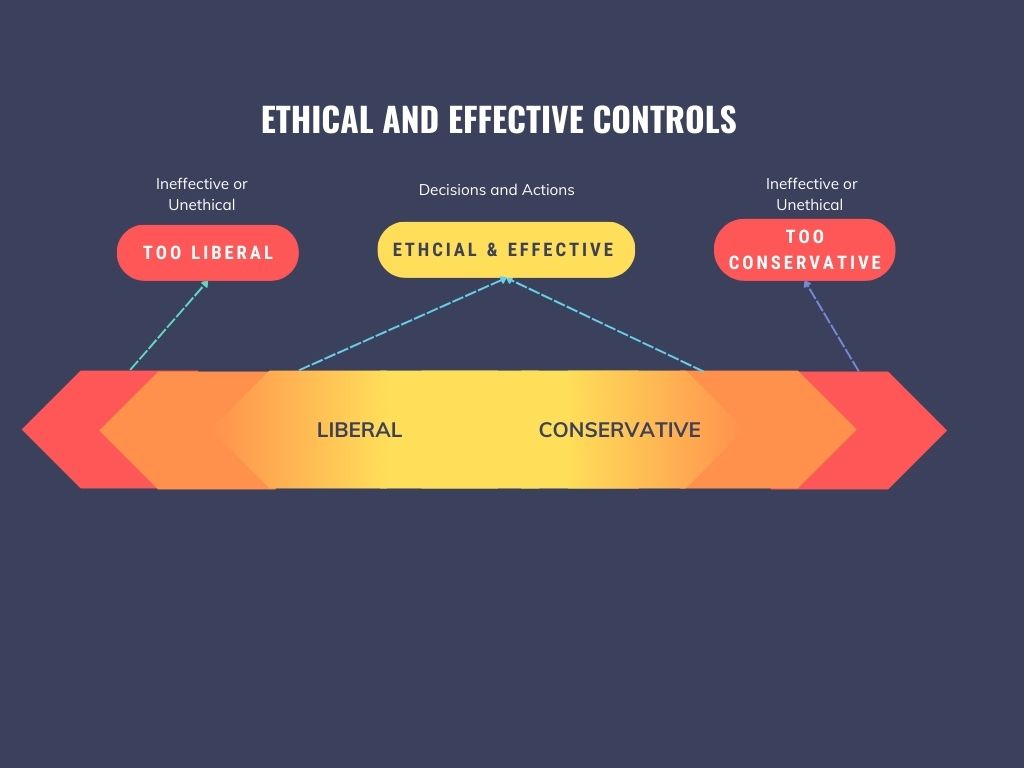

An interpreter must make quick and effective ethically based decisions. The Ethical and Effective Decision-Making continuum is an excellent model (Dean & Pollard, 2001). In particular, when working with Deaf children, you need to be willing and able to move seamlessly across the continuum (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dean & Pollard (2001) Ethical and effective controls

In pediatric settings you will find yourself on the liberal side of the continuum (left). Liberal interpreting means you may need to step out of your role and intervene on behalf of the child. For example, during a therapy session, the interpreter may notice that the Deaf child is becoming frustrated and is about to cry. It is proper and considered on the liberal end of the continuum, and still ethical to stop the session and share that information with the healthcare provider.

During adult medical appointments, a Deaf adult is able to share that kind of information on their own behalf. During pediatric appointments if the interpreter feels that the Deaf child is leaving scared and uninformed, let the healthcare provider know your observations and communicate the Deaf child’s facial expressions (they may seem obvious to you but are not to the provider or even the parent). The healthcare provider will assume the child and parent have more ability to communicate than they do. And an interpreter can ask the healthcare provider to reiterate or clarify a message while still in the session.

At times you will find it best serves the Deaf patient to interpret on the conservative side (right) of the continuum. For example, you may need to strictly interpret a Deaf teen’s message, even if that means uses offensive language. The parent, or the healthcare provider, may expect the interpreter to “clean it up,” to not curse or use inappropriate language. An interpreter needs constantly read the room and ethically render the interpretation on the continuum between liberal and conservative decisions.

It is imperative that an interpreter help put the Deaf child at ease. Interpreters working with children should smile and be approachable. Simple kindness and respect will go a long way in gaining the trust of the Deaf child, parent, and healthcare provider. For younger children, be willing to play. While that is certainly not the role of an interpreter per se, it helps to build rapport with the Deaf child. Observe their cues, if they are unwilling to make eye contact or appear shy, it is okay to “dial down” your approach. The important thing is the Deaf child becomes comfortable with the interpreter being in the room.

A question that often gets raised is if the interpreter should continue interpreting even if the Deaf child is not looking; the short answer is “yes.” The Deaf patient will at least learn the information is accessible during a medical appointment. Receptive language is ALWAYS better than expressive language and the Deaf child may understand more than they can express. There are rare and few exceptions when an interpreter should stop interpreting. For example, after a long day of testing for the Deaf patient and the child is fully engaged in play.

Closing Thoughts

Interpreting for a Deaf child in a healthcare setting is multi-layered and can be unexpectedly complicated. The demands for this specialized setting and population, require the interpreter to make thoughtful decisions through an ethical lens. The ideas and suggestions here may help you prepare and allow you to best serve Deaf children in a pediatric setting. The presence of interpreters at healthcare appointments is important and will have lifelong impacts for Deaf children.

Key Takeaways

Quick Tips for Success

- Be flexible.

- Go outside your comfort zone.

- Be friendly and smile.

- Treat the client like a child, not an adult.

- Find out as much as possible prior to the appointment.

- Communicate as much as possible. Remember, you are the language authority in the room.

Activities

Introduction:

Deaf children may not have the language to share their experiences; however, they still have those experiences. Their brains continue to take in information regardless of language ability. Language deprivation does not mean a Deaf child is incapable of understanding. They may not have sufficient language to receive or express what they understand. Because of this, it is our job as interpreters to figure out how to lessen the gap of getting the information to the Deaf child in the most accessible way possible.

Activity #1:

- Find a five-to-ten-minute clip of a cartoon. While it is on mute, record yourself interpreting what you see on TV. Be sure to include facial expressions and character movements in the interpretation.

- Play the cartoon and your video side by side and compare interpretation. Worry less about actual vocabulary and notice more your expressions and movements compared to the cartoon characters.

Activity #2:

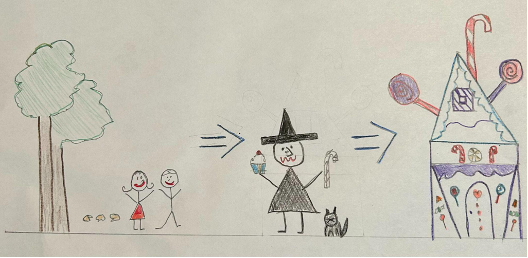

Consider the famous Grimm fairy tale Hansel and Gretel. The following is a picture that I drew to show how it looks pictorially representing English in a linear language structure:

Compare this drawing that does not follow a linear language structure:

Draw one picture that tells the story of one of your favorite childhood stories. In only one picture you should be able to convey the basics of the story, without using arrows or a linear structed drawing. You do not need to be an artist (as seen above!); you can use stick figures (as seen above!). Share your results with family or friends and see if they recognize the story from your drawing. Have fun!

Discussion Questions

References

Barnett, S. (1999). Clinical and cultural issues in caring for deaf people. Family Medicine, 31(1), 17–22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9987607/

Barnett, S., & Franks, P. (2002). Health care utilization and adults who are deaf: Relationship with age at onset of deafness. Health Services Research, 37(1), 105–120. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11949915/

Dean, R., & Pollard, R. (2001). Application of demand-control theory to sign language interpreting: Implications for stress and interpreter training. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 6(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/6.1.1

Caselli, N., Pyers, J., & Liberman, A. (2021, May). Deaf children of hearing parents have age-level vocabulary growth when exposed to American Sign Language by 6 months of age. The Journal of Pediatrics, 232(1), 229–236. https://www.jpeds.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0022-3476%2821%2900036-6

Gupta, R. C. (2023, April). Preparing your child for visits to the doctor. Nemours Kids Health. https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/dr-visits.html#:~:text=Your%20child%20will%20feel%20more,you’re%20honest%20with%20them

Heuttel, K. L., & Rothstein, W. G. (2001). HIV/AIDS knowledge and information sources among deaf and hard of hearing college students. American Annals of the Deaf, 146(3), 280–286. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2012.0067

Hoglind, T. (2018, October 11). Healthcare language barriers affect Deaf people, too. Boston University School of Public Health. https://www.bu.edu/sph/news/articles/2018/healthcare-language-barriers-affect-deaf-people-too/

Margellos-Anast, H., Estarziau, M., & Kaufman, G. (2006). Cardiovascular disease knowledge among culturally Deaf patients in Chicago. Preventive Medicine, 42(3), 235–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.012

McKee, M. M., Paasche-Orlow, M. K., Winters, P. C., Fiscella, K., Zazove, P., Sen, A., & Pearson, T. (2015). Assessing health literacy in Deaf American Sign Language users. Journal of Health Communication, 20(sup2), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1066468

Montoya, L., Morina-Meyer, B., & McHenry, M. (2019, June 1-4). Working With Children in a Pediatric Setting. American Deafness and Rehabilitation Association, ADARA-AMPHL Conference, Baltimore, MD. https://issuu.com/adara-amphl/docs/2019_adara-amphl_conference_program

National Association of the Deaf. (2014, June 18). Position statement on early cognitive and language development and education of deaf and hard of hearing children. https://www.nad.org/about-us/position-statements/position-statement-on-early-cognitive-and-language-development-and-education-of-deaf-and-hard-of-hearing-children/

Peinkofer, J. R. (1994). HIV education for the deaf, a vulnerable minority. Public Health Reports, 109(3), 390–396. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8190862/

Pollard R. (1998) Psychopathology. In: Marschark M, editor. Psychological Perspectives on Deafness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. pp. 171–197.

Psychology Today. (2023). Learned helplessness. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/learned-helplessness

Rowley, K., & Sive, D. (2021, November). Preventing language deprivation. BATOD Magazine, 32–34. https://www.batod.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Preventing-Language-Deprivation.pdf

Tamaskar, P., Malila, T., Stern, C., Gorenflo, D., Meador, H., & Zazove, P. (2000, June). Preventative attitudes and beliefs of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals, Archives of Family Medicine, 9(6), 518–525.

World Federation of the Deaf. (2018). The deaf gap in healthcare. https://wfdeaf.org/news/deaf-gap-healthcare/